The Palace of Pleasure," He Seems to Have Started Work on This Before He Left Seven Oaks in 1561

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Critical Analysis of William Shakespeare's: Romeo and Juliet

International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume 8, Issue 10, October 2018 270 ISSN 2250-3153 A Critical Analysis of William Shakespeare’s: Romeo and Juliet * Rahmatullah Katawazai * Department of English Language and Literature, Kandahar University, Afghanistan DOI: 10.29322/IJSRP.8.10.2018.p8235 http://dx.doi.org/10.29322/IJSRP.8.10.2018.p8235 Abstract- This study is conducted to explore the artistic values The love and hate both go similarly in the play of Romeo and of William Shakespeare’s most well-known play: Romeo and Juliet. It means that in the same time, it gives the feelings of Juliet and for indicating all the possible sides of the play sadness and happiness to the audience and readers of it. including characters, setting, plot summary, historical background, themes and other literary figures’ perspectives Index Terms- Romeo and Juliet, historical background, about the play critically. Romeo and Juliet has been praised as characters, plot summary, theme one of the interesting plays of William Shakespeare not only in I. INTRODUCTION English Literature, but worldwide. All the elements of a play has been used scholarly by William Shakespeare. As Connolly iteratue is the art of expressing emotions and feelings as (2000) mentioned that “Shakespeare wrote Romeo and Juliet L the way they are. Literary figures usually express these early in his career, between 1594-1595, around the same time through some of the genres in the field (literature) as mainly; as the comedies Love’s Labour’s Lost and A Midsummer fiction, non-fiction and play. These genres include various Night’s Dream. -

An Introduction to Shakespeare, by 1

An Introduction to Shakespeare, by 1 An Introduction to Shakespeare, by H. N. MacCracken and F. E. Pierce and W. H. Durham This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: An Introduction to Shakespeare Author: H. N. MacCracken F. E. Pierce W. H. Durham Release Date: January 16, 2010 [EBook #30982] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 An Introduction to Shakespeare, by 2 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK AN INTRODUCTION TO SHAKESPEARE *** Produced by Al Haines [Frontispiece: TITLE-PAGE OF THE FIRST FOLIO, 1628 The first collected edition of Shakespeare's Plays (From the copy in the New York Public Library)] AN INTRODUCTION TO SHAKESPEARE BY H. N. MacCRACKEN, PH.D. F. E. PIERCE, PH.D. AND W. H. DURHAM, PH.D. OF THE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LITERATURE IN THE SHEFFIELD SCIENTIFIC SCHOOL OF YALE UNIVERSITY New York THE MACMILLAN COMPANY 1925 All rights reserved PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA An Introduction to Shakespeare, by 3 COPYRIGHT, 1910, By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY. Set up and electrotyped. Published September, 1910. Reprinted April, December, 1911; September, 1912; July, 1913; July, 1914; December, 1915; November, 1916; May, 1918; July, 1919; November, 1920; September, 1921; June, 1923; January, 1925. Norwood Press J. S. Cushing Co.--Berwick & Smith Co. Norwood, Mass., U.S.A. {v} PREFACE The advances made in Shakespearean scholarship within the last half-dozen years seem to justify the writing of another manual for school and college use. -

Timon of Athens by William Shakespeare

Timon of Athens By William Shakespeare A Shakespeare in the Ruins Study Guide April 2018 Contents Introduction Notes on the Life of Timon of Athens by William Shakespeare Dramatis Personæ Timon of Athens Synopsis Anticipation and Reaction Guides Reading the Play Aloud Additional Activities Introduction When you first heard that Shakespeare In The Ruins was doing Timon of Athens this year, what did you think? To be honest, my first thought was ―Hmmmmmmm… I‘ve never even read that one. I‘ve seen the title listed with his other works, but I have no idea what it‘s about.‖ And then I read it. And then I read it again. It‘s an odd little play. Different from all of the other Shakespeare plays that we‘re so familiar with. But like all of those better known works, this one is about being human and some of the experiences that we might encounter along our life journeys. The play begins with the Poet and Painter philosophising about – what else? – life and art. Soon Timon and Flavius appear, speaking of Timon‘s financial status. From there we meet an assortment of characters including a merchant, friends, and flatterers. Timon‘s journey, according to Artistic Director Michelle Boulet, begins with excessive naivete that is later replaced by misanthropy and cynicism. The play, according to most Shakespeare resources, is classified as a Tragedy, so we know it will not end well for our title character. But, as always, there are lessons to be learned by the characters and by the audience. Students and teachers will enjoy discussing some of the play‘s essential questions about friendship, money, and what it means to be human. -

Hospitality in Shakespeare

Hospitality in Shakespeare: The Case of The Merchant of Venice , Troilus and Cressida and Timon of Athens Sophie Emma Battell A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of English, Communication and Philosophy Cardiff University 2017 Summary This thesis analyses hospitality in three of Shakespeare’s plays: The Merchant of Venice (c. 1596-7), Troilus and Cressida ( c. 1601-2) and Timon of Athens (c. 1606-7). It draws on ideas from Derrida and other recent theorists to argue that Shakespeare treats hospitality as the site of urgent ethical inquiry. Far more than a mechanical part of the stage business that brings characters on and off the performance space and into contact with one another, hospitality is allied to the darker visions of these troubling plays. Hospitality is a means by which Shakespeare confronts ideas about death and mourning, betrayal, and the problem of time and transience, encouraging us to reconsider what it means to be truly welcoming. That the three plays studied are not traditionally linked is important. The intention is not to shape the plays into a new group, but rather to demonstrate that Shakespeare’s staging of hospitality is far - reaching in its openness. Again, while the thesis is informed by Der rida’s writings, its approach is through close readings of the texts. Throughout, the thesis is careful not to prioritise big moments of spectacle over more subtle explorations of the subject. Thus, the chapter on The Merchant of Venice explores the sounds that fill the play and its concern with our senses. -

Revisiting Shakespeare's Problem Plays: the Merchant of Venice

Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of English Language and Literature REVISITING SHAKESPEARE’S PROBLEM PLAYS: THE MERCHANT OF VENICE, HAMLET AND MEASURE FOR MEASURE Emine Seda ÇAĞLAYAN MAZANOĞLU Ph.D. Dissertation Ankara, 2017 REVISITING SHAKESPEARE’S PROBLEM PLAYS: THE MERCHANT OF VENICE, HAMLET AND MEASURE FOR MEASURE Emine Seda ÇAĞLAYAN MAZANOĞLU Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of English Language and Literature Ph.D. Dissertation Ankara, 2017 v For Hayriye Gülden, Sertaç Süleyman and Talat Serhat ÇAĞLAYAN and Emre MAZANOĞLU vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to express my endless gratitude to my supervisor, Prof. Dr. A. Deniz BOZER for her great support, everlasting patience and invaluable guidance. Through her extensive knowledge and experience, she has been a model for me. She has been a source of inspiration for my future academic career and made it possible for me to recognise the things that I can achieve. I am extremely grateful to Prof. Dr. Himmet UMUNÇ, Prof. Dr. Burçin EROL, Asst. Prof. Dr. Şebnem KAYA and Asst. Prof. Dr. Evrim DOĞAN ADANUR for their scholarly support and invaluable suggestions. I would also like to thank Dr. Suganthi John and Michelle Devereux who supported me by their constant motivation at CARE at the University of Birmingham. They were the two angels whom I feel myself very lucky to meet and work with. I also would like to thank Prof. Dr. Michael Dobson, the director of the Shakespeare Institute and all the members of the Institute who opened up new academic horizons to me. I would like to thank Dr. -

Parolles the Play “All’S Well That Ends Well”

THE MAN PAROLLES THE PLAY “ALL’S WELL THAT ENDS WELL” THE FACTS WRITTEN: Shakespeare wrote the play in 1602 between “Troilus and Cressida” and “Measure for Measure”; all three “comedies” are considered to be Shakespeare’s “Problem Plays”. PUBLISHED: The play was not published until its inclusion twenty-one years later in the 1623 Folio. AGE: The Bard was 38 years old when he wrote the play. (Shakespeare B.1564-D.1616) CHRONO: The play falls in 25th place in the canon of 39 plays -- a dark period in Shakespeare’s writing, coincidentally just prior to the 1603 recurrence of bubonic plague which temporarily closed the theaters off and on until the Great Fire of London in 1666 which effectively halted the tragic epidemic. GENRE: Even though the play is considered a “comedy” it defies being placed in that genre. “Modern criticism has sought other terms than comedy and the label ‘problem play’ was first attached to it in 1896 by English scholar, Frederick S. Boas. Frederick S. Boas (1896): The play produces neither “simple joy nor pain; we are excited, fascinated, perplexed; for the issues raised preclude a completely satisfactory outcome”. The Arden Shakespeare scholars add to Boas’ comments: “This is arguably the very source of the play’s interest for us, as it Page 2 complicates and holds up for criticism the wish-fulfilling logic of comedy itself. Helena desires to assure herself and us that: ‘All’s well that ends well yet, / Though time seems so adverse and means unfit.’ Even if the action ‘ends well’, the ‘means unfit’ by which it does so must challenge the comic claim. -

Romeo & Juliet

Romeo & Juliet by William Shakespeare The title page of Romeo & Juliet from the First Folio of Shakespeare’s plays, published in 1623. Handsome bound facsimiles of Romeo & Juliet , published in the Globe Folios series in association with the British Library, are available from the shop, price £9.99. Each volume includes an introduction by the foremost First Folio scholar, Anthony James West. Sources, early Performance and Publication Shakespeare’s principal sources for Romeo & Romeo & Juliet was almost certainly first Juliet were a long narrative poem called The performed by Shakespeare’s company, the Tragicall Historye of Romeus and Juliet by Arthur Chamberlain’s Men, in or around 1596 – a Brooke, first published in 1562 and, to a lesser ‘lyrical’ period of Shakespeare’s writing career degree, the prose romance Rhomeo and Julietta which also includes A Midsummer Night’s Dream, by William Painter. Both sources were based Richard II and many of the Sonnets . No records on a French version of the Italian story Giulietta exist to tell us where it was first seen, but it e Romeo first published in about 1530. Such is likely to have been either the Theatre or the The Curtain Theatre, Shoreditch (to the right), where Italian ‘novelles’ were popular reading in Curtain playhouse in Shoreditch. It has been Romeo & Juliet was probably first performed in or around Shakespeare’s time and Painter’s collection, suggested that Richard Burbage, the company’s 1596. A detail from Abram Booth’s ‘View of London from The Palace of Pleasure , was singled out by the leading man, took the role of Romeo (he would the North’. -

William Shakespeare Peter Dubois

ROMEO AND JULIET CURRICULUM BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE DIRECTED BY GUIDE PETER DUBOIS TABLE OF CONTENTS Common Core Standards 3 Massachusetts Standards in Theatre 4 Artists 5 Themes for Writing and Assessment 7 Mastery Assessment 10 Further Exploration 13 Suggested Activities 17 References and Resources 20 Notes 21 © Huntington Theatre Company Boston, MA 02115 February 2019 No portion of this curriculum guide may be reproduced without written permission from the Huntington Theatre Company’s Department of Education & Community Programs Inquiries should be directed to: Alexandra Smith | Interim Co-Director of Education [email protected] This curriculum guide was prepared for the Huntington Theatre Company by: Ivy Ryan | Teaching Artist Fellow Dylan C. Wack | Education Apprentice Alexandra Smith | Interim Co-Director of Education COMMON CORE STANDARDS IN ENGLISH LANGUAGE ARTS STANDARDS: Student Matinee performances and pre-show workshops provide unique opportunities for experiential learning and support various combinations of the Common Core Standards for English Language Arts. They may also support standards in other subject areas such as Social Studies and History, depending on the individual play’s subject matter. Activities are also included in this Curriculum Guide and in our pre-show workshops that support several of the Massachusetts state standards in Theatre. Other arts areas may also be addressed depending on the individual play’s subject matter. Reading Literature: Key Ideas and Details 1 Reading Literature: Craft and Structure 5 • Grade 7: Cite several pieces of textual evidence to support • Grade 7: Analyze how a drama’s or poem’s form or structure analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences (e.g., soliloquy, sonnet) contributes to its meaning. -

Shakespeare Trivia Anthology Canadian Adaptations of Shakespeare Project (CASP) Shakespeare Learning Commons

1 Shakespeare Trivia Anthology Canadian Adaptations of Shakespeare Project (CASP) Shakespeare Learning Commons FACT 1. Shakespeare is thought to have been born on April 23, 1564 and to have died the same day 52 years later. 2. During his lifetime, John Shakespeare (William’s father) did all of these jobs: glove maker, wool-dealer, moneylender, constable, chamberlain, alderman, bailiff, and justice of the peace. 3. Many of Shakespeare’s early sonnets are likely to have been written to another man: Henry Wriothesley, the 3rd Earl of Southampton. 4. In his will, Shakespeare left his wife Anne Hathaway his “second best bed with the furniture.” Second-best bed was not as bad as it sounds because the best bed was reserved for guests. 5. The open-air theatres that Shakespeare’s plays were first performed in were designed in the same style as the bear-baiting gardens (circular buildings with an open roof and a pit in the centre for the bear or the theatre audience). 6. A Google search for “Shakespeare” returns over 119 million hits. That’s more than Michael Jackson (42 million), Avril Lavigne (29 million) and Tiger Woods (21 million) combined. 7. Shakespeare invented over 1700 commonly used words in English (like “madcap,” “obscene,” “puking,” “outbreak,” “watchdog,” “addiction,” “cold-blooded,” “secure,” and “torture”). 8. Shakespeare’s plays have a vocabulary of some 17,000 words, four times what a well-educated English speaker would have. Shakespeare used 29,066 different words out of 884,647 words in all. 9. Shakespeare was so skilled with words that he used 7000 words only once––more than occur in the whole of the King James Bible. -

Notes on Timon of Athens: Origins, Analyses and Academic Notes of Same / Sdmace 2013

Notes on Timon of Athens: Origins, Analyses and academic notes of same / sdmace 2013 NOTES TAKEN FROM VARIOUS SOURCES Timon of Athens is a play by William Shakespeare about the fortunes of an Athenian named Timon (and probably influenced by the philosopher of the same name, as well), generally regarded as one of his most obscure and difficult works until recently. Originally grouped with the tragedies, it is generally considered such, but some scholars group it with the problem plays. “Timon of Athens” is believed to have first been performed between 1607 and 1608, whereas the text is believed to have first been printed in 1623 as a part of the First Folio. ORIGIN: Timon of Athens may refer to a historical figure who lived during the era of the Peloponnesian War. Or, more likely, to Timon of Phlius (c. 320 BC – c. 230 BC) who was a Greek skeptic philosopher, a pupil of Pyrrho, and a celebrated writer of satirical poems called Silloi. He was born in Phlius, moved to Megara, and then he returned home and married. He next went to Elis with his wife, and heard Pyrrho, whose tenets he adopted. He also lived on the Hellespont, and taught at Chalcedon, before moving to Athens, where he lived until his death. His writings were said to have been very numerous. He composed poetry, tragedies, satiric dramas, and comedies, of which very little remains. His most famous composition was his Silloi, a satirical account of famous philosophers, living and dead, in hexameter verse. The Silloi has not survived intact, but it is mentioned and quoted by several ancient authors. -

1607 the LIFE of TIMON of ATHENS William Shakespeare

1607 THE LIFE OF TIMON OF ATHENS William Shakespeare Shakespeare, William (1564-1616) - English dramatist and poet widely regarded as the greatest and most influential writer in all of world literature. The richness of Shakespeare’s genius transcends time; his keen observation and psychological insight are, to this day, without rival. Timon of Athens (1607) - A tragedy in which Timon loses his wealth and finds that he has lost his friends as well.He leaves Athens to live in a cave where he finds a treasure and meets the banished general, Alcibiades. DRAMATIS PERSONAE TIMON of Athens LUCIUS LUCULLUS SEMPRONIUS flattering lords VENTIDIUS, one of Timon’s false friends ALCIBIADES, an Athenian captain APEMANTUS, a churlish philosopher FLAVIUS, steward to Timon FLAMINIUS LUCILIUS SERVILIUS Timon’s servants CAPHIS PHILOTUS TITUS HORTENSIUS servants to Timon’s creditors POET PAINTER JEWELLER MERCHANT MERCER AN OLD ATHENIAN THREE STRANGERS A PAGE A FOOL PHRYNIA TIMANDRA mistresses to Alcibiades CUPID AMAZONS in the Masque Lords, Senators, Officers, Soldiers, Servants, Thieves, and Attendants SCENE: Athens and the neighbouring woods ACT I SCENE I. Athens. TIMON’S house Enter POET, PAINTER, JEWELLER, MERCHANT, and MERCER, at several doors POET Good day, sir. PAINTER I am glad y’are well. POET I have not seen you long; how goes the world? PAINTER It wears, sir, as it grows. POET Ay, that’s well known. But what particular rarity? What strange, Which manifold record not matches? See, Magic of bounty, all these spirits thy power Hath conjur’d to attend! I know the merchant. PAINTER I know them both; th’ other’s a jeweller. -

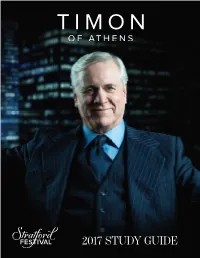

Study Guide 2017 Study Guide

2017 STUDY GUIDE 2017 STUDY GUIDE EDUCATION PROGRAM PARTNER TIMON OF ATHENS BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE DIRECTOR STEPHEN OUIMETTE TOOLS FOR TEACHERS sponsored by PRODUCTION SUPPORT is generously provided by Cec & Linda Rorabeck INDIVIDUAL THEATRE SPONSORS Support for the 2017 Support for the 2017 Support for the 2017 Support for the 2017 season of the Festival season of the Avon season of the Tom season of the Studio Theatre is generously Theatre is generously Patterson Theatre is Theatre is generously provided by provided by the generously provided by provided by Daniel Bernstein & Birmingham family Richard Rooney & Sandra & Jim Pitblado Claire Foerster Laura Dinner CORPORATE THEATRE PARTNER Sponsor for the 2017 season of the Tom Patterson Theatre Cover: Joseph Ziegler. Photography by Lynda Churilla. TABLE OF CONTENTS The Place The Stratford Festival Story ........................................................................................ 1 The Play The Playwright: William Shakespeare ........................................................................ 3 A Shakespearean Timeline ......................................................................................... 4 Plot Synopsis ............................................................................................................... 6 Sources, Origins and Production History .................................................................... 7 Curriculum Connections ............................................................................................. 9 Themes and