Host-Plant Acceptance by the Carrot Fly: Some Underlying Mechanisms and the Relationship to Host-Plant Suitability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

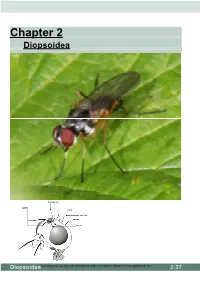

Chapter 2 Diopsoidea

Chapter 2 Diopsoidea DiopsoideaTeaching material only, not intended for wider circulation. [email protected] 2:37 Diptera: Acalyptrates DIOPSOI D EA 50: Tanypezidae 53 ------ Base of tarsomere 1 of hind tarsus very slightly projecting ventrally; male with small stout black setae on hind trochanter and posterior base of hind femur. Postocellar bristles strong, at least half as long as upper orbital seta; one dorsocentral and three orbital setae present Tanypeza ----------------------------------------- 55 2 spp.; Maine to Alberta and Georgia; Steyskal 1965 ---------- Base of tarsomere 1 of hind tarsus strongly projecting ventrally, about twice as deep as remainder of tarsomere 1 (Fig. 3); male without special setae on hind trochanter and hind femur. Postocellar bristles weak, less than half as long as upper orbital bristle; one to three dor socentral and zero to two orbital bristles present non-British ------------------------------------------ 54 54 ------ Only one orbital bristle present, situated at top of head; one dorsocentral bristle present --------------------- Scipopeza Enderlein Neotropical ---------- Two or three each of orbital and dorsocentral bristles present ---------------------Neotanypeza Hendel Neotropical Tanypeza Fallén, 1820 One species 55 ------ A black species with a silvery patch on the vertex and each side of front of frons. Tho- rax with notopleural depression silvery and pleurae with silvery patches. Palpi black, prominent and flat. Ocellar bristles small; two pairs of fronto orbital bristles; only one (outer) pair of vertical bristles. Frons slightly narrower in the male than in the female, but not with eyes almost touching). Four scutellar, no sternopleural, two postalar and one supra-alar bristles; (the anterior supra-alar bristle not present). Wings with upcurved discal cell (11) as in members of the Micropezidae. -

Diptera: Psilidae)

Eur. J. Entomol. 103: 183–192, 2006 ISSN 1210-5759 The identity of Pseudopsila, description of a new subgenus of Psila, and redefinition of Psila sensu lato (Diptera: Psilidae) MATTHIAS BUCK and STEPHEN A. MARSHALL Department of Environmental Biology, University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario N1G 2W1, Canada; e-mail: [email protected] Key words. Psila, Xenopsila, Pseudopsila, Psilidae, phylogeny, redefinition, subgenera, key, new synonymy, new subgenus, New World, morphology, male genitalia, egg Abstract. The type species of Pseudopsila Johnson, P. fallax (Loew), and two related species are found to belong in Psila s. str., and Pseudopsila is thus synonymized with Psila Meigen. The remaining species formerly included in Pseudopsila form a monophyletic group here described as Xenopsila Buck subgen. n. [i.e., Psila (Xenopsila) collaris Loew comb. n., P. (X.) bivittata Loew comb. n., P. (X.) lateralis Loew comb. n., P. (X.) arbustorum Shatalkin comb. n., P. (X.) nemoralis Shatalkin comb. n., P. (X.) tetrachaeta (Shatalkin) comb. n., P. (X.) maculipennis (Frey) comb. n., P. (X.) nigricollis (Frey) comb. n., P. (X.) nigrohumera (Wang & Yang) comb. n.]. A key to the Nearctic species of Xenopsila and the Psila fallax-group is provided. The placement of Xenopsila in Psila s. l. is confirmed by newly recognised synapomorphies of the egg stage. The somewhat questionable monophyly of Psila s. l. is con- firmed based on these new synapomorphies, thereby slightly expanding its taxonomic limits to also include Asiopsila Shatalkin. The morphology of the male genitalia of Xenopsila is discussed in detail, clarifying confused homologies and character polarities in the hypandrial complex. Evolutionary trends in the development of the hypandrium in the subfamily Psilinae are discussed. -

Micropezids & Tanypezids Newsletter 1

Micropezids & Tanypezids Stilt & Stalk Fly Recording Scheme Newsletter 1 1999 to 2019 A compilation of news items published in Dipterists Forum Bulletin Recording Scheme background One of a group of UK Diptera Recording Schemes developed within Dipterists Forum. This scheme began with the author’s interest in various Acalypterate Families in 1999. Thanks to the support and cooperation of many members of Dipterists Forum these groups of interest coalesced into just the two Superfamilies Nerioidea & Diopsoidea and so became a Study Group in 2001. The odd name derives from “Stilt-legged flies” and “Stalk flies”. That cooperation involved not just the Contents sending of specimens to me, but also many records and papers. Consequently in 2002, species occurrences began to amass Small Acalypterate Families Study Group and it became a Recording Scheme, with occurrences managed using Recorder. Dipterists Forum Bulletin 48, August 1999 2 Dipterists Forum Bulletin 50, August 2000 2 As Editor of the Dipterists Forum Bulletin it was relatively straightforward to insert short notes into this magazine, a Stilt & Stalk Fly Study Group tactic that has helped popularise many of the other 23 Dipterists Forum Bulletin 51, February 2001 3 Recording Schemes and to encourage Diptera recording in the Dipterists Forum Bulletin 52, August 2001 4 UK. Dipterists Forum Bulletin 53, Spring 2002 4 As this Recording Scheme progressed, several landmarks Stilt & Stalk Fly Recording Scheme were achieved. In 2003 the accumulated records were submitted to the UK’s Global Biodiversity Gateway, the NBN Dipterists Forum Bulletin 54,Autumn 2002 5 Gateway. In other words they were made publicly available to Dipterists Forum Bulletin 55, Spring 2003 6 all for research. -

Notes on New and Interesting Diptera from Norway

© Norwegian Journal of Entomology. 12 December 2011 Notes on new and interesting Diptera from Norway ØIVIND GAMMELMO & GEIR SØLI Gammelmo, Ø. & Søli, G. 2011. Notes on new and interesting Diptera from Norway. Norwegian Journal of Entomology 58, 189–195. Thirty-one species are reported new to Norway, most of them from the Oslofjord-area. The species are: Phoridae: Borophaga agilis (Meigen, 1830), Borophaga incrassata (Meigen, 1830), Diplonevra abbreviata (von Roser, 1840), Diplonevra florescens (Turton, 1801), Diplonevra funebris (Meigen, 1830), Diplonevra pilosella (Schmitz, 1927), Megaselia barbulata (Wood, 1909), Megaselia subconvexa (Lundbeck, 1920), Phalacrotophora berolinensis Schmitz, 1920, Woodiphora retroversa (Wood, 1908); Pipunculidae: Chalarus latifrons Hardy, 1943, Chalarus spurius (Fallen, 1816), Tomosvaryella littoralis (Becker, 1897); Micropezidae: Cnodacophora stylifera (Loew, 1870); Stongylophthalmyidae: Strongylophthalmyia pictipes Frey, 1935; Psilidae: Psila fimetaria (Linnaeus, 1761); Tephritidae: Campiglossa argyrocephala (Loew, 1844), Orellia falcata (Scopoli, 1763); Lauxaniidae: Trigonometopus frontalis (Meigen, 1830); Anthomyzidae: Anthomyza macra Czerny, 1928; Asteiidae: Asteia amoena Meigen, 1830; Sphaeroceridae: Leptocera oldenbergi (Duda, 1918), Pullimosina moesta (Villeneuve, 1918); Drosophilidae: Hirtodrosophila oldenbergi (Duda, 1924), Scaptodrosophila deflexa (Duda, 1924), Scaptomyza teinoptera Hackman, 1955, Drosophila limbata von Roser, 1840, Hirtodrosophila trivittata (Strobl, 1893); Ephydridae: Nostima -

Diversity Studies in Koitajoki (3.4 MB, Pdf)

Metsähallituksen luonnonsuojelujulkaisuja. Sarja A, No 131 Nature Protection Publications of the Finnish Forest and Park Service. Series A, No 131 Diversity studies in Koitajoki Area (North Karelian Biosphere Reserve, Ilomantsi, Finland) Timo J. Hokkanen (editor) Timo J. Hokkanen (editor) North Karelian Biosphere Reserve FIN-82900 Ilomantsi, FINLAND [email protected] The authors of the publication are responsible for the contents. The publication is not an official statement of Metsähallitus. Julkaisun sisällöstä vastaavat tekijät, eikä julkaisuun voida vedota Metsähallituksen virallisesna kannanottona. ISSN 1235-6549 ISBN 952-446-325-3 Oy Edita Ab Helsinki 2001 Cover picture:Veli-Matti Väänänen © Metsähallitus 2001 DOCUMENTATION PAGE Published by Date of publication Metsähallitus 14.9.2001 Author(s) Type of publication Research report Timo J. Hokkanen (editor) Commissioned by Date of assignment / Date of the research contract Title of publication Diversity studies in Koitajoki Area (North Karelian Biosphere Reserve, Ilomantsi, Finland) Parts of publication Abstract The mature forests of Koitajoki Area in Ilomantsi were studied in the North Karelian Biosphere Reserve Finnish – Russian researches in 1993-1998. Russian researchers from Petrozavodsk (Karelian Research Centre) , St Peters- burg (Komarov Botanical Institute) and Moscow (Moscow State University) were involved in the studies. The goal of the researches was to study the biolgical value of the prevailing forest fragments. An index of the value of the forest fragments was compiled. The index includes the amount and quality and suc- cession of the decaying wood in the sites. The groups studied were Coleoptera, Diptera, Hymenoptera and ap- hyllophoraceous fungi. Coleoptera species were were most numerous in Tapionaho, where there were over 200 spedies found of the total number of 282 found in the studies. -

Checklist of Lithuanian Diptera

NAUJOS IR RETOS LIETUVOS VABZDŽIŲ RŪŠYS. 27 tomas 105 NEW DATA ON SEVERAL DIPTERA FAMILIES IN LITHUANIA ANDRIUS PETRAŠIŪNAS1, ERIKAS LUTOVINOVAS2 1Department of Zoology, Vilnius University, M. K. Čiurlionio 21, LT-03101 Vilnius, Lithuania. E-mail: [email protected] 2Nature Research Centre, Akademijos 2, LT-08412 Vilnius, Lithuania. E-mails: [email protected], [email protected] Introduction The latest list of Lithuanian Diptera included 3311 species (Pakalniškis et al., 2006) and later publications during the past nine years added about 220 more, mainly from the following families: Nematocera: Limoniidae and Tipulidae (Podėnas, 2008), Trichoceridae (Petrašiūnas & Visarčuk, 2007; Petrašiūnas, 2008), Chironomidae (Móra & Kovács, 2009), Bolitophilidae, Keroplatidae, Mycetophilidae and Sciaridae (Kurina et al., 2011); Brachycera: Asilidae (Lutovinovas, 2012a), Syrphidae (Lutovinovas, 2007; 2012b; Lutovinovas & Kinduris, 2013), Pallopteridae (Lutovinovas, 2013), Ulidiidae (Lutovinovas & Petrašiūnas, 2013), Tephritidae (Lutovinovas, 2014), Fanniidae and Muscidae (Lutovinovas, 2007; Lutovinovas & Rozkošný, 2009), Tachinidae (Lutovinovas, 2007, 2009, 2010, 2012c). Fauna of only the few Diptera families in Lithuania (out of 90 families recorded) is studied comparatively better (e.g. Agromyzidae, Limoniidae, Simuliidae, Syrphidae, Tipulidae, Tachinidae), with majority of the families getting weaker or only sporadic attention, if at all. New species are being recorded every time and more effort is devoted, proving that there is still much to do in Diptera research in Lithuania. The following publication provides new data on fifteen Diptera families in Lithuania with most attention paid to several anthophilous families (e.g. Bombyliidae, Conopidae and Stratiomyidae). Material and Methods Most specimens were caught by sweeping the vegetation and the few others were identified from photographs. -

The Woolston Eyes Conservation Group

The Woolston Eyes Conservation Group Annual Report 2014 WOOLSTON EYES CONSERVATION GROUP ANNUAL REPORT 2014 CONTENTS Page Chairman’s Report B. Ankers 2 Weather B. Martin 3 Systematic List B. Martin 6 D. Hackett D. Spencer D. Riley D. Bowman WeBS Counts B. Martin 54 Ringing Report M. Miles 56 Recoveries and Controls M. Miles 63 Migration Watch D. Steel 71 Butterfly Report D. Hackett 75 Odonata Report Brian Baird 82 Willow Tit Report Alan Rustell 90 Heteroptera and Diptera Phil Brighton 92 Mammals D. Bowman 99 Acknowledgments D. Bowman 104 Officers of Woolston Eyes Conservation Group 105 © No part of this report may be reproduced in any way without the prior permission of the Editor. 1 CHAIRMAN’S REPORT A special welcome to all those members taking the Annual Report for the first time now that it is available online. I am sure you will find it an enjoyable and informative read. Our income comes from the sale of permits and any grants that we manage to acquire, and all monies are put back into the Reserve. As you are aware, the management of the Reserve has always been undertaken by volunteers, but specialist work is done by our contractors so this is where a lot of our income is spent. I would therefore like to thank all of you for your continued support in renewing your permits, sending in donations and, in two cases, for bequests leaving money to the Reserve in wills. You will see on the cover of our report the wonderful drawing produced free of charge to us by the highly thought of wildlife artist Colin Woolf. -

CHKO Broumovsko)

ACTA MUSEI REGINAEHRADECENSIS S. A., 34 (2014): 155-158 ISBN: 978-80-87686-03-4 Příspěvek k poznání některých čeledí dvoukřídlých (Diptera) v lomu Rožmitál (CHKO Broumovsko) Contribution to the knowledge of some families of Diptera in the Rožmitál quarry (Czech Republic, Northeast Bohemia, Broumovsko Protected Landscape Area) Bohuslav Mocek 1, 2) 1) Muzeum Východních Čech v Hradci Králové, Eliščino nabřeží 465, CZ – 500 01, Hradec Králové, e-mail: [email protected] 2) Filozofická fakulta, Univerzita Hradec Králové, centrum interdisciplinárního výzkumu, Rokitanského 62, CZ – 500 03, Hradec Králové Abstract: The list of 117 species of Diptera of 23 families is the main content of the article. This part of the material collected in the years 2000 – 2014 was determi- ned. The fauna of Diptera comprises meadow, wetland and forest species. Xylomya maculata (family Xylomyidae) is the most important find. This species is bound on original beech forests with old trees (relict species) and was published as new for Bohemia (MOCEK & MIKÁT 2010). Key words: Diptera, faunistics, Rožmitál quarry, Broumovsko PLA, Northeast Bohemia, Czech Republic ÚVOD severního lomu), převažuje jihozápadní sklon terénu směrem do Broumovské kotliny. Průzkum entomofauny v roce 2000 a letech 2008 a 2009 Z geologického hlediska patří území lokality k sedimen- byl součástí širšího biologického průzkumu pro účely po- tárně eruptivnímu komplexu hornin, který je součástí vnitro- souzení vlivu postupující těžby do 2. ochranné zóny CHKO sudetské pánve. Geologický podklad tvoří melafyry a tufy. Broumovsko a projekt ekologické obnovy vrchu Homole po Klimaticky leží území na rozhraní oblastí mírně teplé ukončení těžby (SAMKOVÁ & kol. 2000, MOCEK & kol. -

Managing Carrot Rust Fly

A Monthly Report on Pesticides and Related Environmental Issues March 2003 • Issue No. 203 • http://aenews.wsu.edu Managing Carrot Rust Fly In Search of Alternatives for a Tough Customer Dr. David Muehleisen, Andrew Bary, Dr. Craig Cogger, Dr. Carol Miles, Amanda Johnson and Dr. Marcia Ostrom, WSU, and Terry Carkner, Terry’s Berries Organic Farm The State of Washington is the number one producer of processing carrots in the United States and the fourth largest producer of fresh market carrots (Washington Agricultural Statistics Service 2001). This accounts for 33% of the processed carrots and almost 4% of the fresh carrots produced in the nation. Carrot production generated $29.8 million dollars for Washington State in 2000 (Sorensen 2000). The leading carrot-producing counties are Benton and Franklin in the eastern part of the state and Cowlitz and Skagit west of the Cascade Mountains. As of 2000 Washington had 5000 acres of processing carrots and 3000 acres of fresh market carrots (Sorensen 2000). Approximately 2% of the carrots grown in Washington were grown organically (Sorensen 2000). About the Pest Arguably the most important pest of carrots, particularly on the western side of the state, is the carrot rust fly (Psila rosae Fabricius) (Figure 1, a and b). The rust fly adult is about 6-8 mm long with a shiny black thorax and abdomen, a reddish-brown head, and yellow legs. The adult female lays its eggs in the soil at the base of the carrot. Six to ten days later the larva hatches and feeds on the carrot root, rendering the carrots impossible to market. -

Ecology and Integrated Pest Management of the Carrot Rust Fly (Psila Rosae (Fabricius, 1794)), in the Holland Marsh, Ontario

Ecology and Integrated Pest Management of the Carrot Rust Fly (Psila rosae (Fabricius, 1794)), in the Holland Marsh, Ontario by Jason Lemay A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Plant Agriculture Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Jason Lemay, December, 2016 ABSTRACT Ecology and Integrated Pest Management of the Carrot Rust Fly (Psila rosae (Fabricius, 1794)), in the Holland Marsh, Ontario Jason Paul Lemay Advisors: University of Guelph, 2016 Professor M.R. McDonald Professor C. Scott-Dupree This thesis is an investigation of the ecobiology and integrated pest management (IPM) of the carrot rust fly (Psila rosae) (CRF) in the Holland Marsh, Ontario. The Holland Marsh is a major carrot producing area in North America. Carrot rust fly is a serious pest of carrots. An IPM program for CRF is used within the Holland Marsh. Published CRF rearing procedures were found to be inadequately detailed. Improvements to the procedure were identified. Various insecticides, including seed treatments, in-furrow, and post- emergent, were evaluated for their effectiveness to control CRF. No conclusions could be made on their effectiveness due to low pest pressure. The natural enemy species composition in the Holland Marsh was determined and known CRF and carrot weevil natural enemies were identified. The IPM program used in the Holland Marsh was not found to be detrimental to the natural enemy species richness or abundance. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my advisors, Drs. Mary Ruth McDonald and Cynthia Scott-Dupree for their continued assistance during this project, for challenging me to continue when things were not going well. -

Drosophila | Other Diptera | Ephemeroptera

NATIONAL AGRICULTURAL LIBRARY ARCHIVED FILE Archived files are provided for reference purposes only. This file was current when produced, but is no longer maintained and may now be outdated. Content may not appear in full or in its original format. All links external to the document have been deactivated. For additional information, see http://pubs.nal.usda.gov. United States Department of Agriculture Information Resources on the Care and Use of Insects Agricultural 1968-2004 Research Service AWIC Resource Series No. 25 National Agricultural June 2004 Library Compiled by: Animal Welfare Gregg B. Goodman, M.S. Information Center Animal Welfare Information Center National Agricultural Library U.S. Department of Agriculture Published by: U. S. Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service National Agricultural Library Animal Welfare Information Center Beltsville, Maryland 20705 Contact us : http://awic.nal.usda.gov/contact-us Web site: http://awic.nal.usda.gov Policies and Links Adult Giant Brown Cricket Insecta > Orthoptera > Acrididae Tropidacris dux (Drury) Photographer: Ronald F. Billings Texas Forest Service www.insectimages.org Contents How to Use This Guide Insect Models for Biomedical Research [pdf] Laboratory Care / Research | Biocontrol | Toxicology World Wide Web Resources How to Use This Guide* Insects offer an incredible advantage for many different fields of research. They are relatively easy to rear and maintain. Their short life spans also allow for reduced times to complete comprehensive experimental studies. The introductory chapter in this publication highlights some extraordinary biomedical applications. Since insects are so ubiquitous in modeling various complex systems such as nervous, reproduction, digestive, and respiratory, they are the obvious choice for alternative research strategies. -

Chapter 9 Biodiversity of Diptera

Chapter 9 Biodiversity of Diptera Gregory W. Courtney1, Thomas Pape2, Jeffrey H. Skevington3, and Bradley J. Sinclair4 1 Department of Entomology, 432 Science II, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa 50011 USA 2 Natural History Museum of Denmark, Zoological Museum, Universitetsparken 15, DK – 2100 Copenhagen Denmark 3 Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Canadian National Collection of Insects, Arachnids and Nematodes, K.W. Neatby Building, 960 Carling Avenue, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0C6 Canada 4 Entomology – Ontario Plant Laboratories, Canadian Food Inspection Agency, K.W. Neatby Building, 960 Carling Avenue, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0C6 Canada Insect Biodiversity: Science and Society, 1st edition. Edited by R. Foottit and P. Adler © 2009 Blackwell Publishing, ISBN 978-1-4051-5142-9 185 he Diptera, commonly called true flies or other organic materials that are liquified or can be two-winged flies, are a familiar group of dissolved or suspended in saliva or regurgitated fluid T insects that includes, among many others, (e.g., Calliphoridae, Micropezidae, and Muscidae). The black flies, fruit flies, horse flies, house flies, midges, adults of some groups are predaceous (e.g., Asilidae, and mosquitoes. The Diptera are among the most Empididae, and some Scathophagidae), whereas those diverse insect orders, with estimates of described of a few Diptera (e.g., Deuterophlebiidae and Oestridae) richness ranging from 120,000 to 150,000 species lack mouthparts completely, do not feed, and live for (Colless and McAlpine 1991, Schumann 1992, Brown onlyabrieftime. 2001, Merritt et al. 2003). Our world tally of more As holometabolous insects that undergo complete than 152,000 described species (Table 9.1) is based metamorphosis, the Diptera have a life cycle that primarily on figures extracted from the ‘BioSystematic includes a series of distinct stages or instars.