MARIUS by Marcel Pagnol (1931) Directed by Alexander Korda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

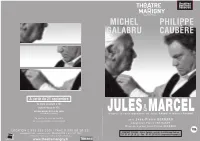

Michel GALABRU Philippe CAUBÈRE Reliaient

salle popesco MICHEL PHILIPPE GALABRU CAUBÈRE A partir du 21 septembre du mardi au samedi à 19h matinée dimanche 17h prix des places de 25 à 45 euros JULES& MARCEL (hors frais de réservations) d’après la correspondance de Jules RAIMU et Marcel PAGNOL Un spectacle créé au festival avec Jean-Pierre BERNARD de la correspondance de Grignan adaptation Pierre TRÉ-HARDY Cohen/Cosmos © Photo Serge Mise en espace Jean-Pierre BERNARD LOCATION 0 892 222 333* / FNAC 0 892 68 36 22* 19h MAGASINS FNAC - www.fnac.com / RÉSATHÉÂTRE 0 892 707 705* CONTACT PRESSE : Pierre Cordier, assisté de Guillaume Andreu CARREFOUR, AGENCES ET POINTS DE VENTE HABITUELS Tél. 01 43 26 20 22 - Fax : 01 43 29 54 59 - [email protected] /mn RCS PARIS B 572 123 792 - Licence 750 2656 - Saison 2010 - Photo Serge Cohen/Cosmos B 572 123 792 - Licence 750 2656 Saison 2010 Photo Serge RCS PARIS € www.theatremarigny.fr *0,34 JULES& MARCEL« Il est fâcheux d’être fâchés » Note d’intention Origine du spectacle Le spectacle « Mon cher Jules, il faut que tu sois bougrement fâché avec moi pour ne pas répondre à une lettre injurieuse qui n’avait d’autre but que Il s’agit d’une lecture de lettres échangées entre l’écrivain Michel Galabru, Nicolas Pagnol (petit fils de Marcel Pagnol) de commencer une dispute…». Ces correspondances entre Raimu et Marcel Pagnol tissent ainsi la toile de leur éternelle amitié, mêlée de mauvaise foi tru- Marcel Pagnol et Raimu, son ami et acteur fétiche. Le et Isabelle Nohain Raimu (petite fille de Raimu) étaient culente, de fâcheries épiques, d’admiration réciproque, de pudeur, d’humour, de souvenirs, de secrets… et de savoureuses envolées, drôles, fraîches et vives thème central est « le Cinéma », passion qui a relié ces venus assister, en août 2006, à une adaptation de la trilo- comme l’eau des sources de leur Provence. -

Propaganda, Cinema and the American Character in World War Ii Theodore Kornweibel, Jr

humphrey bogart's Sahara propaganda, cinema and the american character in world war ii theodore kornweibel, jr. How and why a people responds affirmatively to momentous events in the life of its nation is an intriguing question for the social historian. Part of the answer may be found in the degree to which a populace can connect such events to traditional (and often idealistic) themes in its culture, themes which have had wide currency and restatement. This kind of identification can be seen particularly in wartime; twice in this century large segments of the American population rallied around the call to preserve democracy under the guise of fighting a "war to end all wars" and another to preserve the "four freedoms." But popular perceptions of these global conflicts were not without both deliberate and unconscious manipulation in many areas of the culture, including commercial motion pictures. Hollywood produced hundreds of feature films during World War II which depicted facets of that conflict on the domestic homefront, the soil of friendly Allies and far-flung battlefields. Many of the films showed no more than a crude addition of the war theme to plots that would have been filmed anyway in peacetime, such as gangster stories and musical comedies. But other movies reached a deeper level in subtly linking the war to American traditions and ideals. Sahara,1 Columbia Pictures' biggest money-maker in 1943, starring Humphrey Bogart in a finely understated performance, is such a motion picture. Students of American culture will find Sahara and its never-filmed predecessor script, "Trans-Sahara," artifacts especially useful in ex amining two phenomena: the process of government pressure on 0026-3079/81/2201-0005S01.50/0 5 movie studios to ensure that the "approved" war. -

Using Multimedia to Teach French Language and Culture APPROVED

Copyright by Florence Marie Lemoine 2012 The Report Committee for Florence Marie Lemoine Certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: Using Multimedia to Teach French Language and Culture APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Carl Blyth Elaine Horwitz Using Multimedia to Teach French Language and Culture by Florence Marie Lemoine, B.A. Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin December 2012 Dedication To all French learners, may you have fun along the process of learning this language! Acknowledgements I would like to thank all of you who have made this career switch to French teaching possible, in particular my professors at UT - Dr. Blyth, Dr. Horwitz, Dr. Sardegna, Dr. Pulido, Dr. Schallert, and Dr. Tissières - and all my friends in Foreign Language Education. I also wish to thank my husband Roland and my two sons Théo and Marius for their help and support during the past two years. v Abstract Using Multimedia to Teach French Language and Culture Florence Marie Lemoine, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2012 Supervisor: Carl Blyth In order for the study of French to survive in American higher education, it will be necessary to adopt a pedagogy that motivates learners as well as teaches them both language and culture. I argue that the judicious use of visual materials (film, video and graphic novels) is ideal for this undertaking. I further assert—based upon numerous sources from fields such as Second Language Acquisition, cognitive psychology, anthropology and sociolinguistics--that language and culture are inseparable, and that visual materials provide the necessary context to facilitate the teaching of both. -

Film Film Film Film

City of Darkness, City of Light is the first ever book-length study of the cinematic represen- tation of Paris in the films of the émigré film- PHILLIPS CITY OF LIGHT ALASTAIR CITY OF DARKNESS, makers, who found the capital a first refuge from FILM FILMFILM Hitler. In coming to Paris – a privileged site in terms of production, exhibition and the cine- CULTURE CULTURE matic imaginary of French film culture – these IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION experienced film professionals also encounter- ed a darker side: hostility towards Germans, anti-Semitism and boycotts from French indus- try personnel, afraid of losing their jobs to for- eigners. The book juxtaposes the cinematic por- trayal of Paris in the films of Robert Siodmak, Billy Wilder, Fritz Lang, Anatole Litvak and others with wider social and cultural debates about the city in cinema. Alastair Phillips lectures in Film Stud- ies in the Department of Film, Theatre & Television at the University of Reading, UK. CITY OF Darkness CITY OF ISBN 90-5356-634-1 Light ÉMIGRÉ FILMMAKERS IN PARIS 1929-1939 9 789053 566343 ALASTAIR PHILLIPS Amsterdam University Press Amsterdam University Press WWW.AUP.NL City of Darkness, City of Light City of Darkness, City of Light Émigré Filmmakers in Paris 1929-1939 Alastair Phillips Amsterdam University Press For my mother and father, and in memory of my auntie and uncle Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam isbn 90 5356 633 3 (hardback) isbn 90 5356 634 1 (paperback) nur 674 © Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2004 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, me- chanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permis- sion of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. -

RESISTANCE MADE in HOLLYWOOD: American Movies on Nazi Germany, 1939-1945

1 RESISTANCE MADE IN HOLLYWOOD: American Movies on Nazi Germany, 1939-1945 Mercer Brady Senior Honors Thesis in History University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Department of History Advisor: Prof. Karen Hagemann Co-Reader: Prof. Fitz Brundage Date: March 16, 2020 2 Acknowledgements I want to thank Dr. Karen Hagemann. I had not worked with Dr. Hagemann before this process; she took a chance on me by becoming my advisor. I thought that I would be unable to pursue an honors thesis. By being my advisor, she made this experience possible. Her interest and dedication to my work exceeded my expectations. My thesis greatly benefited from her input. Thank you, Dr. Hagemann, for your generosity with your time and genuine interest in this thesis and its success. Thank you to Dr. Fitz Brundage for his helpful comments and willingness to be my second reader. I would also like to thank Dr. Michelle King for her valuable suggestions and support throughout this process. I am very grateful for Dr. Hagemann and Dr. King. Thank you both for keeping me motivated and believing in my work. Thank you to my roommates, Julia Wunder, Waverly Leonard, and Jamie Antinori, for being so supportive. They understood when I could not be social and continued to be there for me. They saw more of the actual writing of this thesis than anyone else. Thank you for being great listeners and wonderful friends. Thank you also to my parents, Joe and Krista Brady, for their unwavering encouragement and trust in my judgment. I would also like to thank my sister, Mahlon Brady, for being willing to hear about subjects that are out of her sphere of interest. -

Liste-Electorale-Cncc-College-Non-Eip-200730.Pdf

LISTE DES ELECTEURS 1 COLLEGE NON EIP ELECTIONS DU CONSEIL NATIONAL Dépouillement le mercredi 30 septembre 2020 NOM PRENOM 2 ADRESSE2 ABADIE Anne-Laure 38 rue de Langelle 65100 Lourdes ABADIE Sandrine 1220, avenue de l'europe 82000 Montauban ABASTADO David 71 avenue Victor Hugo 75116 Paris ABAZ Didier 25, bis avenue Marcel Dassault 31500 Toulouse ABBO André 28, rue Colonel Colonna D'ornano BP 44 20180 Ajaccio Cedex 1 ABDELLAOUI Noureddine 1 Rue Du Docteur Gey 60110 Meru ABDERRAHMANE Zohra 9 rue Tronchet 69006 Lyon ABEHSERA Cedric 7 Rue Chateaubriand 75008 Paris ABEHSERA Laurent 9 Rue Moncey 75009 Paris ABEHSSERA Albert 112 bis rue Cardinet 75017 Paris ABEILLE Jean-Michel 9, Rue d'arcole 13006 Marseille ABEL Edith 18 rue de l'ours 68200 Mulhouse ABERGEL Alain 143 Rue De La Pompe 75116 Paris ABERGEL Laurent 9 rue Pyramide 75001 Paris ABERGEL Prosper 75/79 rue Rateau Bat H3 93120 La Courneuve ABETTAN Elisabeth 32, rue Berzelius 75017 Paris ABHAY Mélanie 67 Rue Jean de la Fontaine 75016 Paris ABITBOL Ilan 87, rue Marceau Bâtiment BP 176 93100 Montreuil ABITBOL Luc 12 rue La Boétie 75008 Paris ABITBOL Michaël 45 avenue Charles de Gaulle 92200 Neuilly Sur Seine ABJEAN Patrick 13 rue Lebrun Malard 56230 Questembert ABOU Hamidou 4, rue du Fer à Moulin 75005 Paris ABOUKAD Soufyane 10, route d'espagne 31100 Toulouse ABOULKER Guillaume 100 rue de Commandant Rolland 13008 Marseille ACCARDI Frédéric 46 Boulevard Exelmans 75116 Paris ACCIAIOLI Jean Charles 321, boulevard Mège Mouries 83300 Draguignan ACCOSSATO-ARANCIO Céline 3319 Route des Escaillouns 06390 Berre Les Alpes ACH Yves Alain 31 Rue Du Theatre 75015 Paris ACHARD DE LA VENTE Guillain 29 Bis rue de la Prairie 78120 Rambouillet ACHDJIAN Chahé 146 A, rue Galliéni 92100 Boulogne-Billancourt ACHTE Stéphane 184 rue Sadi Carnot 59320 Haubourdin ACIER Roger 21 Avenue de Messine 75008 Paris ACKER Romain 6 rue Pierre Gilles de Gennes 76130 Mont Saint Aignan ACQUAVIVA Robert 480, Avenue du Prado B.P. -

Spring 2019 Film Calendar

National Gallery of Art Film Spring 19 I Am Cuba p27 Special Events 11 A Cuba Compendium 25 Janie Geiser 29 Walt Whitman Bicentennial 31 The Arboretum Cycle of Nathaniel Dorsky 33 Roberto Rossellini: The War Trilogy 37 Reinventing Realism: New Cinema from Romania 41 Spring 2019 offers digital restorations of classic titles, special events including a live performance by Alloy Orchestra, and several series of archival and contem- porary films from around the world. In conjunction with the exhibition The Life of Animals in Japanese Art, the Gallery presents Japanese documentaries on animals, including several screenings of the city symphony Tokyo Waka. Film series include A Cuba Compendium, surveying how Cuba has been and continues to be portrayed and examined through film, including an in-person discussion with Cuban directors Rodrigo and Sebastián Barriuso; a celebra- tion of Walt Whitman on the occasion of his bicen- tennial; recent restorations of Roberto Rossellini’s classic War Trilogy; and New Cinema from Romania, a series showcasing seven feature length films made since 2017. Other events include an artist’s talk by Los Angeles-based artist Janie Geiser, followed by a program of her recent short films; a presentation of Nathaniel Dorsky’s 16mm silent The Arboretum Cycle; the Washington premieres of Gray House and The Image Book; a program of films on and about motherhood to celebrate Mother’s Day; the recently re-released Mystery of Picasso; and more. 2Tokyo Waka p17 3 April 6 Sat 2:00 La Religieuse p11 7 Sun 4:00 Rosenwald p12 13 Sat 12:30 A Cuba Compendium: Tania Libre p25 2:30 A Cuba Compendium: Coco Fusco: Recent Videos p26 14 Sun 4:00 Gray House p12 20 Sat 2:00 A Cuba Compendium: Cuba: Battle of the 10,000,000 p26 4:00 A Cuba Compendium: I Am Cuba p27 21 Sun 2:00 The Mystery of Picasso p13 4:30 The Mystery of Picasso p13 27 Sat 2:30 A Cuba Compendium: The Translator p27 Films are shown in the East Building Auditorium, in original formats whenever possible. -

A Mode of Production and Distribution

Chapter Three A Mode of Production and Distribution An Economic Concept: “The Small Budget Film,” Was it Myth or Reality? t has often been assumed that the New Wave provoked a sudden Ibreak in the production practices of French cinema, by favoring small budget films. In an industry characterized by an inflationary spiral of ever-increasing production costs, this phenomenon is sufficiently original to warrant investigation. Did most of the films considered to be part of this movement correspond to this notion of a small budget? We would first have to ask: what, in 1959, was a “small budget” movie? The average cost of a film increased from roughly $218,000 in 1955 to $300,000 in 1959. That year, at the moment of the emergence of the New Wave, 133 French films were produced; of these, 33 cost more than $400,000 and 74 cost more than $200,000. That leaves 26 films with a budget of less than $200,000, or “low budget productions;” however, that can hardly be used as an adequate criterion for movies to qualify as “New Wave.”1 Even so, this budgetary trait has often been employed to establish a genealogy for the movement. It involves, primarily, “marginal” films produced outside the dominant commercial system. Two Small Budget Films, “Outside the System” From the point of view of their mode of production, two titles are often imposed as reference points: Jean-Pierre Melville’s self-produced Silence of 49 A Mode of Production and Distribution the Sea, 1947, and Agnes Varda’s La Pointe courte (Short Point), made seven years later, in 1954. -

The Third Man 2004

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Drew Bassett Rob White: The Third Man 2004 https://doi.org/10.17192/ep2004.2.1856 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Rezension / review Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Bassett, Drew: Rob White: The Third Man. In: MEDIENwissenschaft: Rezensionen | Reviews, Jg. 21 (2004), Nr. 2, S. 250– 251. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17192/ep2004.2.1856. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under a Deposit License (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, non-transferable, individual, and limited right for using this persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses document. This document is solely intended for your personal, Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für non-commercial use. All copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute, or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the conditions of vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder use stated above. anderweitig nutzen. Mit der Verwendung dieses Dokuments erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen an. Fotogrqfie 1111d Film Roh White: The Third Man London: BFI Publishing 2003 (BFI Film Classics). -

HP0221 Teddy Darvas

BECTU History Project - Interview No. 221 [Copyright BECTU] Transcription Date: Interview Dates: 8 November 1991 Interviewer: John Legard Interviewee: Teddy Darvas, Editor Tape 1 Side A (Side 1) John Legard: Teddy, let us start with your early days. Can you tell us where you were born and who your parents were and perhaps a little about that part of your life? The beginning. Teddy Darvas: My father was a very poor Jewish boy who was the oldest of, I have forgotten how many brothers and sisters. His father, my grandfather, was a shoemaker or a cobbler who, I think, preferred being in the cafe having a drink and seeing friends. So he never had much money and my father was the one brilliant person who went to school and eventually to university. He won all the prizes at Gymnasium, which is the secondary school, like a grammar school. John Legard: Now, tell me, what part or the world are we talking about? Teddy Darvas: This is Budapest. He was born in Budapest and whenever he won any prizes which were gold sovereigns, all that money went on clothes and things for brothers and sisters. And it was in this Gymnasium that he met Alexander Korda who was in a parallel form. My father was standing for Student's Union and he found somebody was working against him and that turned out to be Alexander Korda, of course the family name was Kelner. They became the very, very greatest of friends. Alex was always known as Laci which is Ladislav really - I don't know why. -

Ronald Davis Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts

Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts in America Southern Methodist University The Southern Methodist University Oral History Program was begun in 1972 and is part of the University’s DeGolyer Institute for American Studies. The goal is to gather primary source material for future writers and cultural historians on all branches of the performing arts- opera, ballet, the concert stage, theatre, films, radio, television, burlesque, vaudeville, popular music, jazz, the circus, and miscellaneous amateur and local productions. The Collection is particularly strong, however, in the areas of motion pictures and popular music and includes interviews with celebrated performers as well as a wide variety of behind-the-scenes personnel, several of whom are now deceased. Most interviews are biographical in nature although some are focused exclusively on a single topic of historical importance. The Program aims at balancing national developments with examples from local history. Interviews with members of the Dallas Little Theatre, therefore, serve to illustrate a nation-wide movement, while film exhibition across the country is exemplified by the Interstate Theater Circuit of Texas. The interviews have all been conducted by trained historians, who attempt to view artistic achievements against a broad social and cultural backdrop. Many of the persons interviewed, because of educational limitations or various extenuating circumstances, would never write down their experiences, and therefore valuable information on our nation’s cultural heritage would be lost if it were not for the S.M.U. Oral History Program. Interviewees are selected on the strength of (1) their contribution to the performing arts in America, (2) their unique position in a given art form, and (3) availability. -

Kipling, Masculinity and Empire

Kunapipi Volume 18 Issue 1 Article 10 1996 America's Raj: Kipling, Masculinity and Empire Nicholas J. Cull Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Cull, Nicholas J., America's Raj: Kipling, Masculinity and Empire, Kunapipi, 18(1), 1996. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi/vol18/iss1/10 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] America's Raj: Kipling, Masculinity and Empire Abstract The posters for Gunga Din promised much: 'Thrills for a thousand movies, plundered for one mighty show'. That show was a valentine to the British Raj, in which three sergeants (engagingly played by Cary Grant, Victor McLaglen, and Douglas Fairbanks, Jr.) defeat marauding hoards of 'natives' with the aid of their 'Uncle Tom' water bearer, Gunga Din (Sam Jaffe)[Plate VII]. Audiences loved it. Its racism notwithstanding, even an astute viewer like Bertolt Brecht confessed: 'My heart was touched ... f felt like applauding and laughed in all the right places'. 1 Outwardly the film had little ot do with the United States. Most of the cast were British-born and its screenplay claimed to be 'from the poem by Rudyard Kipling' .2 Yet the film was neither British or faithful ot Kipling, but solidly American: directed by George Stevens for RKO, with a screenplay by Oxford-educated Joel Sayre and Stevens's regular collaborator Fred Guiol.3 This journal article is available in Kunapipi: https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi/vol18/iss1/10 America's Raj: Kipling, Masculinity, and Empire 85 NICHOLAS J.