HP0221 Teddy Darvas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1

Contents Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances .......... 2 February 7–March 20 Vivien Leigh 100th ......................................... 4 30th Anniversary! 60th Anniversary! Burt Lancaster, Part 1 ...................................... 5 In time for Valentine's Day, and continuing into March, 70mm Print! JOURNEY TO ITALY [Viaggio In Italia] Play Ball! Hollywood and the AFI Silver offers a selection of great movie romances from STARMAN Fri, Feb 21, 7:15; Sat, Feb 22, 1:00; Wed, Feb 26, 9:15 across the decades, from 1930s screwball comedy to Fri, Mar 7, 9:45; Wed, Mar 12, 9:15 British couple Ingrid Bergman and George Sanders see their American Pastime ........................................... 8 the quirky rom-coms of today. This year’s lineup is bigger Jeff Bridges earned a Best Actor Oscar nomination for his portrayal of an Courtesy of RKO Pictures strained marriage come undone on a trip to Naples to dispose Action! The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1 .......... 10 than ever, including a trio of screwball comedies from alien from outer space who adopts the human form of Karen Allen’s recently of Sanders’ deceased uncle’s estate. But after threatening each Courtesy of Hollywood Pictures the magical movie year of 1939, celebrating their 75th Raoul Peck Retrospective ............................... 12 deceased husband in this beguiling, romantic sci-fi from genre innovator John other with divorce and separating for most of the trip, the two anniversaries this year. Carpenter. His starship shot down by U.S. air defenses over Wisconsin, are surprised to find their union rekindled and their spirits moved Festival of New Spanish Cinema .................... -

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy in the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger 1939-1946 Valerie Wilson University College London PhD May 2001 ProQuest Number: U642581 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642581 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946 This thesis will examine the films planned or made by Powell and Pressburger in this period, with these aims: to demonstrate the way the contemporary realities of wartime Britain (political, social, cultural, economic) are represented in these films, and how the realities of British history (together with information supplied by the Ministry of Information and other government ministries) form the basis of much of their propaganda. to chart the changes in the stylistic combination of realism, naturalism, expressionism and surrealism, to show that all of these films are neither purely realist nor seamless products of artifice but carefully constructed narratives which use fantasy genres (spy stories, rural myths, futuristic utopias, dreams and hallucinations) to convey their message. -

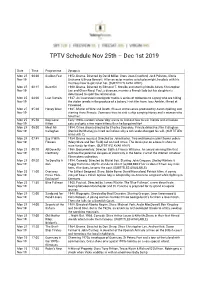

TPTV Schedule Nov 25Th – Dec 1St 2019

TPTV Schedule Nov 25th – Dec 1st 2019 Date Time Programme Synopsis Mon 25 00:00 Sudden Fear 1952. Drama. Directed by David Miller. Stars Joan Crawford, Jack Palance, Gloria Nov 19 Grahame & Bruce Bennett. After an actor marries a rich playwright, he plots with his mistress how to get rid of her. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 25 02:15 Beat Girl 1960. Drama. Directed by Edmond T. Greville and starring Noelle Adam, Christopher Nov 19 Lee and Oliver Reed. Paul, a divorcee, marries a French lady but his daughter is determined to spoil the relationship. Mon 25 04:00 Last Curtain 1937. An insurance investigator tracks a series of robberies to a gang who are hiding Nov 19 the stolen jewels in the produce of a bakery. First film from Joss Ambler, filmed at Pinewood. Mon 25 05:20 Honey West 1965. Matter of Wife and Death. Classic crime series produced by Aaron Spelling and Nov 19 starring Anne Francis. Someone tries to sink a ship carrying Honey and a woman who hired her. Mon 25 05:50 Dog Gone Early 1940s cartoon where 'dog' wants to find out how to win friends and influence Nov 19 Kitten cats and gets a few more kittens than he bargained for! Mon 25 06:00 Meet Mr 1954. Crime drama directed by Charles Saunders. Private detective Slim Callaghan Nov 19 Callaghan (Derrick De Marney) is hired to find out why a rich uncle changed his will. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 25 07:45 Say It With 1934. Drama musical. Directed by John Baxter. Two well-loved market flower sellers Nov 19 Flowers (Mary Clare and Ben Field) fall on hard times. -

Contenido Estrenos Mexicanos

Contenido estrenos mexicanos ............................................................................120 programas especiales mexicanos .................................. 122 Foro de los Pueblos Indígenas 2019 .......................................... 122 Programa Exilio Español ....................................................................... 123 introducción ...........................................................................................................4 Programa Luis Buñuel ............................................................................. 128 Presentación ............................................................................................................... 5 El Día Después ................................................................................................ 132 ¡Bienvenidos a Morelia! ................................................................................... 7 Feratum Film Festival .............................................................................. 134 Mensaje de la Secretaría de Cultura ....................................................8 ......... 10 Mensaje del Instituto Mexicano de Cinematografía funciones especiales mexicanas .......................................137 17° Festival Internacional de Cine de Morelia ............................11 programas especiales internacionales................148 ...........................................................................................................................12 jurados Programa Agnès Varda ...........................................................................148 -

MARIUS by Marcel Pagnol (1931) Directed by Alexander Korda

PRESS PACK CANNES CLASSICS OFFICIAL SELECTION 2015 MARIUS by Marcel Pagnol (1931) Directed by Alexander Korda Thursday 21 May 2015 at 5pm, Buñuel Theatre Raimu and Pierre Fresnay in Marius by Marcel Pagnol (1931). Directed by Alexander Korda. Film restored in 2015 by the Compagnie Méditerranéenne de Films - MPC and La Cinémathèque Française , with the support of the CNC , the Franco-American Cultural Fund (DGA-MPA-SACEM- WGAW), the backing of ARTE France Unité Cinéma and the Archives Audiovisuelles de Monaco, and the participation of SOGEDA Monaco. The restoration was supervised by Nicolas Pagnol , and Hervé Pichard (La Cinémathèque Française). The work was carried out by DIGIMAGE. Colour grading by Guillaume Schiffman , director of photography. Fanny by Marcel Pagnol (Directed by Marc Allégret, 1932) and César by Marcel Pagnol (1936), which complete Marcel Pagnol's Marseilles trilogy, were also restored in 2015. "All Marseilles, the Marseilles of everyday life, the Marseilles of sunshine and good humour, is here... The whole of the city expresses itself, and a whole race speaks and lives. " René Bizet, Pour vous , 15 October 1931 SOGEDA Monaco LA CINÉMATHÈQUE FRANÇAISE CONTACTS Jean-Christophe Mikhaïloff Elodie Dufour Director of Communications, Press Officer External Relations and Development +33 (0)1 71 19 33 65 +33 (0)1 71 1933 14 - +33 (0)6 23 91 46 27 +33 (0)6 86 83 65 00 [email protected] [email protected] Before restoration After restoration Marius by Marcel Pagnol (1931). Directed by Alexander Korda. 2 The restoration of the Marseilles trilogy begins with Marius "Towards 1925, when I felt as if I was exiled in Paris, I realised that I loved Marseilles and I wanted to express this love by writing a Marseilles play. -

The Amazing Mr Blunden

K graphic The Amazing Mr Blunden UK : 1972 : dir. Lionel Jeffries : Hemdale : 99 min prod: Barry Levinson : scr: Lionel Jeffries : dir.ph.: Gerry Fisher Garry Miller; Lynne Frederick; Marc Granger; Rosalyn Landor ………….……………………… Laurence Naismith; Diana Dors; James Villiers; Madeline Smith; David Lodge; Dorothy Alison Stuart Lock; Deddie Davis Ref: Pages Sources Stills Words Ω Copy on VHS Last Viewed 2065b 3½ 14 3 1,770 - No c1992 Lynne Frederick looks on while brother Garry Warren gets acquainted with an agreeable old spirit… Source: Film Review 1973-74 Leonard Maltin’s TV Movies and Video Halliwell’s Film Guide review: Guide review: “In 1918, a widow and her two children meet a “Dickensian fantasy about a genial ghost who kindly gentleman who offers them work in his takes two children back in time to help two old mansion. Here they meet two ghost mistreated tots. Colourful family film whose children, discover that he is a ghost too, and only liability is a somewhat muddled storyline. travel a hundred years back in time to right a *** ” wicked wrong. Involved ghost story for intellectual children, made generally palatable by oodles of period charm and good acting. ** Speelfilm Encyclopedie review - identical to ” above “Easy period charm.. fills every crevice.” – Clyde Jeavons Film Review 1973-74 review: hardly claim credit for the work of a baby who effortlessly steals every scene he appears in. “Following up his big success with his first film-directing assignment ("THE RAILWAY Jeffries’ laconic method assumes acceptance of CHILDREN") actor Lionel Jeffries stayed the supernatural with an agreeable common with the youngsters in his Hemdale movie sense which stays on the safe side of "THE AMAZING MR BLUNDEN", in smugness, and his ghosts are splendidly solid. -

Shepperton Studios Has Submitted Plans Fo

PRESS RELEASE SHEPPERTON STUDIOS SUBMITS PLANS FOR EXPANSION London, 21st August 2018: Shepperton Studios has submitted plans for the redevelopment and expansion of the world-renowned site in Surrey, England, which will deliver a world class studio with a certain future. A planning application has been lodged with Spelthorne Borough Council seeking consent for the £500 million private sector development project which will deliver an increase in stage space of around 465,000 sq ft and associated support facilities. The development will bring the studio up to the scale and standard of its sister Pinewood Studios and make it a truly world-class facility. The scheme is of national importance and follows on from the Government’s ambition to double the scale of film and high-end television production revenue to £4bn by 2025. Shepperton and Pinewood Studios will be vital facilities if the UK is to achieve this target. The expansion will secure the future of more than 1,500 direct jobs currently based in Spelthorne and maintain the current contribution to the local economy of £181 million Gross Value Added (GVA). Over the construction period 837 jobs per year will be created, including potential for more than 200 jobs in the borough. On completion, Shepperton Studios is expected to boost productivity within the local economy to a total of £322 million (GVA) and will create and sustain a total of 2,796 jobs. Andrew M. Smith, Director, Shepperton Studios said: “The UK is currently missing out on a significant number of international films because of a shortage of sound stages. -

(2020). Pinewood Studios, the Independent Frame, and Innovation

Street, S. (2020). Pinewood Studios, the Independent Frame, and Innovation. In B. R. Jacobson (Ed.), In the Studio: Visual Creation and Its Material Environments (1 ed., pp. 103-121). University of California Press. Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the author accepted manuscript (AAM). The final published version (version of record) is available via University of California Press at https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520297609/in-the-studio . Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ Pinewood Studios, the Independent Frame, and Innovation Sarah Street, University of Bristol British director Darrel Catling reported to the British trade press in February 1948 on the Independent Frame (IF), a new system of film production that had been launched at Pinewood Studios. Catling had recently used it to make Under the Frozen Falls, a short children’s film that had benefited from the IF’s aim to “rationalize that which is largely irrational in film making.”1 He described how his film had been very carefully pre-planned in terms of script, storyboards, and technical plans. Several scenes were pre-staged and filmed without the main cast who were later incorporated into scenes by means of rear projection. Special effects were of paramount importance in reducing the number of sets that needed to be built. -

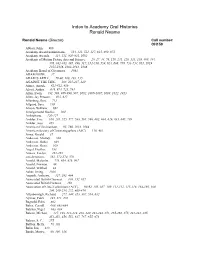

Index to Academy Oral Histories Ronald Neame

Index to Academy Oral Histories Ronald Neame Ronald Neame (Director) Call number: OH159 Abbott, John, 906 Academy Award nominations, 314, 321, 511, 517, 935, 969, 971 Academy Awards, 314, 511, 950-951, 1002 Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Science, 20, 27, 44, 76, 110, 241, 328, 333, 339, 400, 444, 476, 482-483, 495, 498, 517, 552-556, 559, 624, 686, 709, 733-734, 951, 1019, 1055-1056, 1083-1084, 1086 Academy Board of Governors, 1083 ADAM BEDE, 37 ADAM’S APPLE, 79-80, 100, 103, 135 AGAINST THE TIDE, 184, 225-227, 229 Aimee, Anouk, 611-612, 959 Alcott, Arthur, 648, 674, 725, 784 Allen, Irwin, 391, 508, 986-990, 997, 1002, 1006-1007, 1009, 1012, 1013 Allen, Jay Presson, 925, 927 Allenberg, Bert, 713 Allgood, Sara, 239 Alwyn, William, 692 Amalgamated Studios, 209 Ambiphone, 126-127 Ambler, Eric, 166, 201, 525, 577, 588, 595, 598, 602, 604, 626, 635, 645, 709 Ambler, Joss, 265 American Film Institute, 95, 766, 1019, 1084 American Society of Cinematogaphers (ASC), 118, 481 Ames, Gerald, 37 Anderson, Mickey, 366 Anderson, Robin, 893 Anderson, Rona, 929 Angel, Heather, 193 Ankers, Evelyn, 261-263 anti-Semitism, 562, 572-574, 576 Arnold, Malcolm, 773, 864, 876, 907 Arnold, Norman, 88 Arnold, Wilfred, 88 Asher, Irving, 1026 Asquith, Anthony, 127, 292, 404 Associated British Cinemas, 108, 152, 857 Associated British Pictures, 150 Association of Cine-Technicians (ACT), 90-92, 105, 107, 109, 111-112, 115-118, 164-166, 180, 200, 209-210, 272, 469-470 Attenborough, Richard, 277, 340, 353, 387, 554, 632 Aylmer, Felix, 185, 271, 278 Bagnold, Edin, 862 Baker, Carroll, 680, 883-884 Balchin, Nigel, 683, 684 Balcon, Michael, 127, 198, 212-214, 238, 240, 243-244, 251, 265-266, 275, 281-282, 285, 451-453, 456, 552, 637, 767, 855, 878 Balcon, S. -

The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley – UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA)

Recordings at Risk Sample Proposal (Fourth Call) Applicant: The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley – UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) Project: Saving Film Exhibition History: Digitizing Recordings of Guest Speakers at the Pacific Film Archive, 1976 to 1986 Portions of this successful proposal have been provided for the benefit of future Recordings at Risk applicants. Members of CLIR’s independent review panel were particularly impressed by these aspects of the proposal: • The broad scholarly and public appeal of the included filmmakers; • Well-articulated statements of significance and impact; • Strong letters of support from scholars; and, • A plan to interpret rights in a way to maximize access. Please direct any questions to program staff at [email protected] Application: 0000000148 Recordings at Risk Summary ID: 0000000148 Last submitted: Jun 28 2018 05:14 PM (EDT) Application Form Completed - Jun 28 2018 Form for "Application Form" Section 1: Project Summary Applicant Institution (Legal Name) The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley Applicant Institution (Colloquial Name) UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) Project Title (max. 50 words) Saving Film Exhibition History: Digitizing Recordings of Guest Speakers at the Pacific Film Archive, 1976 to 1986 Project Summary (max. 150 words) In conjunction with its world-renowned film exhibition program established in 1971, the UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) began regularly recording guest speakers in its film theater in 1976. The first ten years of these recordings (1976-86) document what has become a hallmark of BAMPFA’s programming: in-person presentations by acclaimed directors, including luminaries of global cinema, groundbreaking independent filmmakers, documentarians, avant-garde artists, and leaders in academic and popular film criticism. -

The Third Man 2004

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Drew Bassett Rob White: The Third Man 2004 https://doi.org/10.17192/ep2004.2.1856 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Rezension / review Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Bassett, Drew: Rob White: The Third Man. In: MEDIENwissenschaft: Rezensionen | Reviews, Jg. 21 (2004), Nr. 2, S. 250– 251. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17192/ep2004.2.1856. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under a Deposit License (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, non-transferable, individual, and limited right for using this persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses document. This document is solely intended for your personal, Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für non-commercial use. All copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute, or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the conditions of vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder use stated above. anderweitig nutzen. Mit der Verwendung dieses Dokuments erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen an. Fotogrqfie 1111d Film Roh White: The Third Man London: BFI Publishing 2003 (BFI Film Classics). -

THTR 363 Syl-Fall

THTR 363: Introduction to Sound Design INSTRUCTOR: Richard K. Thomas, 494-8050 [email protected] OFFICE HOURS: Tuesday: 2:30 – 3:30 p.m., Thursday, 1:30 – 2:30 p.m. PAO 2184 CLASS SCHEDULE: Fall 2011 August 23 Intro to Course (Music As a Foundation, pp. 1 - 6) 25 Lecture: Music Language and Theatre (Music As a Foundation, pp. 6 - 25) 30 Music as a Foundation of Theatre: Origins September 1 Lecture: Primal Elements of Music (Music As a Foundation, pp. 25 – 45) 6 Lecture: Primal Elements of Music (Cont.) 8 Lecture: Primal Elements of Music (Cont.) 13 Lecture: Dramatic Time and Space 17 Lecture: The Function of the Soundscape 20 Group Presentations: General Overview of Design Elements 22 Group Presentations: General Overview of Design Elements (cont.) 27 Watch “More to Live For” in studio (No Rick) 29 No Class: Rick at IRT October 4 Color DVDʼs DUE 6 Color Projects DUE 11 Color (Cont) 13 Octoberbreak 18 Color Composition DUE 20. Time DVDʼs Due 25 Time Projects DUE 27 Time (Cont.) November 1 Time Composition DUE 3 Mass DVDʼs DUE 8 Mass Projects DUE 10 Mass (Cont.) 15 Mass Composition DUE THTR 363 Syllabus: Fall, 2011 Page 2 17 Space DVDʼs DUE 22 Space Projects DUE 24 THANKSGIVING BREAK 29 Space Compositions DUE December 1 Line DVDʼs DUE 6 Line Projects DUE 8 Line (Cont) Final Exam Period: Sonnet Projects Due NOTE: THIS SYLLABUS SUBJECT TO CHANGE!! Course Objectives: The purpose of this course is to introduce students to an aesthetic vocabulary of design elements that is useful in both visual and auditory design.