Black Educator, Poet, Fighter for Equal Rights Part Two Catherine M.Hanchett

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heroes of the Colored Race by Terry Ann Wildman Grade Level

Lesson Plan #2 for the Genius of Freedom: Heroes of the Colored Race by Terry Ann Wildman Grade Level: Upper elementary or middle school Topics: African American leaders Pennsylvania History Standards: 8.1.6 B, 8.2.9 A, 8.3.9 A Pennsylvania Core Standards: 8.5.6-8 A African American History, Prentice Hall textbook: N/A Overview: What is a hero? What defines a hero in one’s culture may be different throughout time and place. Getting our students to think about what constitutes a hero yesterday and today is the focus of this lesson. In the lithograph Heroes of the Colored Race there are three main figures and eight smaller ones. Students will explore who these figures are, why they were placed on the picture in this way, and the background images of life in America in the 1800s. Students will brainstorm and choose heroes of the African American people today and design a similar poster. Materials: Heroes of the Colored Race, Philadelphia, 1881. Biography cards of the 11 figures in the image (attached, to be printed out double-sided) Smartboard, whiteboard, or blackboard Computer access for students Poster board Chart Paper Markers Colored pencils Procedure: 1. Introduce the lesson with images of modern superheroes. Ask students to discuss why these figures are heroes. Decide on a working definition of a hero. Note these qualities on chart paper and display throughout the lesson. 2. Present the image Heroes of the Colored Race on the board. Ask what historic figures students recognize and begin to list those on the board. -

Rochester's Frederick Douglass, Part

ROCHESTER HISTORY Vol. LXVII Fall, 2005 No. 4 Rochester's Frederick Douglass Part Two by Victoria Sandwick Schmitt Underground Railroad From History of New York State, edited by Alexander C. Flick. Volume 7. New York: Columbia University Press, 1935 Courtesy of the Rochester Museum & Science Center, Rochester, NY 1 Front page from Douglass’ Monthly, Courtesy of the Rochester Museum & Science Center, Rochester, NY ROCHESTER HISTORY, published by the Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County. Address correspondence to Local History and Genealogy Division, Rochester Public Library, 115 South Avenue, Rochester, NY 14604. Subscriptions to Rochester History are $8.00 per year by mail. Foreign subscriptions are $12.00 per year, $4.00 per copy for individual issues. Rochester History is funded in part by the Frances Kenyon Publication Fund, established in memory of her sister, Florence Taber Kenyon and her friend Thelma Jeffries. CONOLLY PRINTING-2 c CITY OF ROCHESTER 2007 2 2 Douglass Sheltered Freedom Seekers The Douglass family only lived on Alexander Street for four years before relocating in 1852 to a hillside farm south of the city on what is now South Avenue. Douglass’ farm stood on the outskirts of town, amongst sparsely settled hills not far from the Genesee River. The Douglasses did not sell their Alexander Street house. They held it as the first of several real estate investments, which were the foundation of financial security for them as for many enterprising African American families. 71 The Douglasses’ second residence consisted of a farm with a framed dwelling, orchard and barn. In 2005, a marker in front of School 12 on South Avenue locates the site, near Highland Park. -

©2013 Luis-Alejandro Dinnella-Borrego ALL RIGHTS

©2013 Luis-Alejandro Dinnella-Borrego ALL RIGHTS RESERVED “THAT OUR GOVERNMENT MAY STAND”: AFRICAN AMERICAN POLITICS IN THE POSTBELLUM SOUTH, 1865-1901 By LUIS-ALEJANDRO DINNELLA-BORREGO A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History written under the direction of Mia Bay and Ann Fabian and approved by ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “That Our Government May Stand”: African American Politics in the Postbellum South, 1865-1913 by LUIS-ALEJANDRO DINNELLA-BORREGO Dissertation Director: Mia Bay and Ann Fabian This dissertation provides a fresh examination of black politics in the post-Civil War South by focusing on the careers of six black congressmen after the Civil War: John Mercer Langston of Virginia, James Thomas Rapier of Alabama, Robert Smalls of South Carolina, John Roy Lynch of Mississippi, Josiah Thomas Walls of Florida, and George Henry White of North Carolina. It examines the career trajectories, rhetoric, and policy agendas of these congressmen in order to determine how effectively they represented the wants and needs of the black electorate. The dissertation argues that black congressmen effectively represented and articulated the interests of their constituents. They did so by embracing a policy agenda favoring strong civil rights protections and encompassing a broad vision of economic modernization and expanded access for education. Furthermore, black congressmen embraced their role as national leaders and as spokesmen not only for their congressional districts and states, but for all African Americans throughout the South. -

And He Was No Soft-Tongued Apologist: Fredrick Douglass As a Constitutional Theorist 1865-1895

Providence College DigitalCommons@Providence Theology Faculty Publications Theology 10-1988 And He Was No Soft-Tongued Apologist: Fredrick Douglass as a Constitutional Theorist 1865-1895 Gabriel Pivarnik Providence College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/theology_fac Part of the Religion Commons, and the United States History Commons Pivarnik, Gabriel, "And He Was No Soft-Tongued Apologist: Fredrick Douglass as a Constitutional Theorist 1865-1895" (1988). Theology Faculty Publications. 5. https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/theology_fac/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Theology at DigitalCommons@Providence. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theology Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Providence. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AND HE WAS NO SOFT-TONGUED APOLOGIST: FREDERICK DOUGLASS AS A CONSTITUTIONAL THEORIST, 1865-1895 A Paper Presented to the National Endowment for the Humanities for the Younger Scholars Grant Program 1988 by Robert George Pivarnik October, 1988 And he was no soft-tongued apologist; He spoke straightforward, fearlessly uncowed The sunlight of his truth dispelled the mist, And set in bold relief each dark-hued cloud; To sin and crime he gave their proper hue, And hurled at evil what was evil's due. Paul Lawrence Dunbar, "Frederick Douglass" Acknowledgments I would like to acknowledge the work of Waldo E. Martin on the psychology of Frederick Douglass. If it were not for Martin's research, this project would never have gotten underway. I would also like to thank Elizabeth Ackert and the staff of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Research Library who were instrumen tal in helping me obtain the necessary resources for this work. -

Civil War and Reconstruction Exhibit to Have Permanent Home at National Constitution Center, Beginning May 9, 2019

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Annie Stone, 215-409-6687 Merissa Blum, 215-409-6645 [email protected] [email protected] CIVIL WAR AND RECONSTRUCTION EXHIBIT TO HAVE PERMANENT HOME AT NATIONAL CONSTITUTION CENTER, BEGINNING MAY 9, 2019 Civil War and Reconstruction: The Battle for Freedom and Equality will explore constitutional debates at the heart of the Second Founding, as well as the formation, passage, and impact of the Reconstruction Amendments Philadelphia, PA (January 31, 2019) – On May 9, 2019, the National Constitution Center’s new permanent exhibit—the first in America devoted to exploring the constitutional debates from the Civil War and Reconstruction—will open to the public. The exhibit will feature key figures central to the era— from Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass to John Bingham and Harriet Tubman—and will allow visitors of all ages to learn how the equality promised in the Declaration of Independence was finally inscribed in the Constitution by the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, collectively known as the Reconstruction Amendments. The 3,000-square-foot exhibit, entitled Civil War and Reconstruction: The Battle for Freedom and Equality, will feature over 100 artifacts, including original copies of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, Dred Scott’s signed petition for freedom, a pike purchased by John Brown for an armed raid to free enslaved people, a fragment of the flag that Abraham Lincoln raised at Independence Hall in 1861, and a ballot box marked “colored” from Virginia’s first statewide election that allowed black men to vote in 1867. The exhibit will also feature artifacts from the Civil War Museum of Philadelphia—one of the most significant Civil War collections in the country—housed at and on loan from the Gettysburg Foundation and The Union League of Philadelphia. -

Hiram Rhodes Revels 1827–1901

FORMER MEMBERS H 1870–1887 ������������������������������������������������������������������������ Hiram Rhodes Revels 1827–1901 UNITED STATES SENATOR H 1870–1871 REPUBLICAN FROM MIssIssIPPI freedman his entire life, Hiram Rhodes Revels was the in Indiana, Illinois, Kansas, Kentucky, and Tennessee. A first African American to serve in the U.S. Congress. Although Missouri forbade free blacks to live in the state With his moderate political orientation and oratorical skills for fear they would instigate uprisings, Revels took a honed from years as a preacher, Revels filled a vacant seat pastorate at an AME Church in St. Louis in 1853, noting in the United States Senate in 1870. Just before the Senate that the law was “seldom enforced.” However, Revels later agreed to admit a black man to its ranks on February 25, revealed he had to be careful because of restrictions on his Republican Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts movements. “I sedulously refrained from doing anything sized up the importance of the moment: “All men are that would incite slaves to run away from their masters,” he created equal, says the great Declaration,” Sumner roared, recalled. “It being understood that my object was to preach “and now a great act attests this verity. Today we make the the gospel to them, and improve their moral and spiritual Declaration a reality. The Declaration was only half condition even slave holders were tolerant of me.”5 Despite established by Independence. The greatest duty remained his cautiousness, Revels was imprisoned for preaching behind. In assuring the equal rights of all we complete to the black community in 1854. -

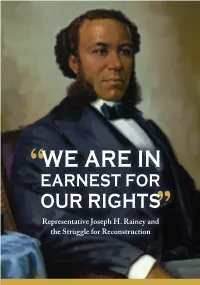

"We Are in Earnest for Our Rights": Representative

Representative Joseph H. Rainey and the Struggle for Reconstruction On the cover: This portrait of Joseph Hayne Rainey, the f irst African American elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, was unveiled in 2005. It hangs in the Capitol. Joseph Hayne Rainey, Simmie Knox, 2004, Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives Representative Joseph H. Rainey and the Struggle for Reconstruction September 2020 2 | “We Are in Earnest for Our Rights” n April 29, 1874, Joseph Hayne Rainey captivity and abolitionists such as Frederick of South Carolina arrived at the U.S. Douglass had long envisioned a day when OCapitol for the start of another legislative day. African Americans would wield power in the Born into slavery, Rainey had become the f irst halls of government. In fact, in 1855, almost African-American Member of the U.S. House 20 years before Rainey presided over the of Representatives when he was sworn in on House, John Mercer Langston—a future U.S. December 12, 1870. In less than four years, he Representative from Virginia—became one of had established himself as a skilled orator and the f irst Black of f iceholders in the United States respected colleague in Congress. upon his election as clerk of Brownhelm, Ohio. Rainey was dressed in a f ine suit and a blue silk But the fact remains that as a Black man in South tie as he took his seat in the back of the chamber Carolina, Joseph Rainey’s trailblazing career in to prepare for the upcoming debate on a American politics was an impossibility before the government funding bill. -

Influential African Americans in History

Influential African Americans in History Directions: Match the number with the correct name and description. The first five people to complete will receive a prize courtesy of The City of Olivette. To be eligible, send your completed worksheet to Kiana Fleming, Communications Manager, at [email protected]. __ Ta-Nehisi Coates is an American author and journalist. Coates gained a wide readership during his time as national correspondent at The Atlantic, where he wrote about cultural, social, and political issues, particularly regarding African Americans and white supremacy. __ Ella Baker was an essential activist during the civil rights movement. She was a field secretary and branch director for the NAACP, a key organizer for Martin Luther King Jr.'s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and was heavily involved in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). SNCC prioritized nonviolent protest, assisted in organizing the 1961 Freedom Rides, and aided in registering Black voters. The Ella Baker Center for Human Rights exists today to carry on her legacy. __ Ernest Davis was an American football player, a halfback who won the Heisman Trophy in 1961 and was its first African-American recipient. Davis played college football for Syracuse University and was the first pick in the 1962 NFL Draft, where he was selected by the Cleveland Browns. __ In 1986, Patricia Bath, an ophthalmologist and laser scientist, invented laserphaco—a device and technique used to remove cataracts and revive patients' eyesight. It is now used internationally. __ Charles Richard Drew, dubbed the "Father of the Blood Bank" by the American Chemical Society, pioneered the research used to discover the effective long-term preservation of blood plasma. -

Hiram Revels—The First African American Senator Hiram Rhodes Revels Was Born in North Carolina in the Year 11 1827

Comprehension and Fluency Name Read the passage. Use the ask and answer questions strategy to help you understand the text. Hiram Revels—The First African American Senator Hiram Rhodes Revels was born in North Carolina in the year 11 1827. Through his whole life he was a good citizen. He was a 24 great leader. He was highly respected. Revels became the first 34 African American to serve in the U.S. Senate. 42 A Hard Time for African Americans 48 Revels was born during a hard time for African Americans. 58 African Americans were treated badly. Most African Americans 66 in the South were enslaved. But Revels grew up as a free African 79 American, or freedman. This meant he could make his own 89 choices. 90 Still, the laws in the South were unfair. African Americans 100 had to work hard jobs. They were not allowed to go to school. 113 Though it was not legal, some freedmen ran schools for African 124 American children. As a child, Revels went to one of these 135 schools. But he was unable to go to college in the South. So he 149 left home to go to college in the North. Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 158 Preaching and Teaching 161 After college, Revels became the pastor of a church. He was 172 a good speaker. He was also a great teacher. He travelled all over 185 the country. He taught fellow African Americans. He knew that 195 this would make them good citizens. Practice • Grade 3 • Unit 5 • Week 4 233 Comprehension and Fluency Name The First African American Senator Revels moved to Natchez, Mississippi in 1866. -

Frederick Douglass and Public Memories of the Haitian Revolution James Lincoln James Madison University

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Spring 2015 Memory as torchlight: Frederick Douglass and public memories of the Haitian Revolution James Lincoln James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the Cultural History Commons, Intellectual History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Lincoln, James, "Memory as torchlight: Frederick Douglass and public memories of the Haitian Revolution" (2015). Masters Theses. 23. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/23 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Memory as Torchlight: Frederick Douglass and Public Memories of the Haitian Revolution James Lincoln A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History May 2015 Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………......1 Chapter 1: The Antebellum Era………………………………………………………….22 Chapter 2: Secession and the Civil War…………………………………………………66 Chapter 3: Reconstruction and the Post-War Years……………………………………112 Epilogue………………………………………………………………………………...150 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………154 ii Abstract The following explores how Frederick Douglass used memoires of the Haitian Revolution in various public forums throughout the nineteenth century. Specifically, it analyzes both how Douglass articulated specific public memories of the Haitian Revolution and why his articulations changed over time. Additional context is added to the present analysis as Douglass’ various articulations are also compared to those of other individuals who were expressing their memories at the same time. -

Legislation Especially for the Negro?

Wycoff: LEGISLATION ESPECIALLY FOR THE NEGRO? THE BLACK PRESS RESPONDS TO LEGISLATION ESPECIALLY FOR THE NEGRO? THE BLACK PRESS RESPONDS TO EARLY SUPREME COURT CIVIL RIGHTS DECISIONS David Wycofft I. INTRODUCTION ....................... 2. We object to being put on a level with II. THE FOURTEENTH AND FIFTEENTH them ............................. 68 AMENDMENTS BECOME BUT HIDEOUS VII. CONCLUSION .......................... 71 M O CKERIES ............................ III. EARNESTLY DISCUSSING THE I. INTRODUCTION DECISIO NS ............................. The years 1873-1883 form perhaps the most im- IV. FEDERALISM ........................... portant decade in United States constitutional history.' A. PRESERVING THE MAIN FEATURES OF In the course of deciding a steady stream of cases in- THE GENERAL SYSTEM ................ volving the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth B. THE CAUSE OF ALL OUR WOES ....... amendments, 2 the Supreme Court laid the basis for the V. CLASS LEGISLATION ................... next century of the constitutional law of civil rights and VI. CLASS LEGISLATION IN THE BLACK civil liberties. Unfortunately, it was a "dreadful dec- PR E SS .................................. ade." In decision after decision, the Court struck down A. THE BANE OF THE NEGRO Is federal laws designed to protect civil rights and civil lib- LEGISLATION ESPECIALLY FOR THE erties, and devitalized the new amendments. N EGRO .............................. These early civil rights decisions of the United B. The Negro Is A Citizen And Must Be States Supreme Court provoked a significant response Protected ............................ in the African American community. Discussion of the 1. The same rights as are enjoyed by other decisions, especially the Civil Rights Cases (1883), was 4a people ............................ major theme in the African American press of the time. t Law Clerk, Honorable James T. -

Test Your Knowledge of Black History WHO AM I

Test your knowledge of Black History 1. Black History Month, which emerged 4. Which is widely known as the 7. Black History Month falls in from an event known as Negro History birthplace of hip-hop? February because which two Week, was the brainchild of this historical important historical figures have A. figure. Harlem birthdays in the month of February? B. The Bronx A. John Lewis C. Thomas Dorsey C. Detroit A. Frederick Douglass and Madam C.J Walker B. Carter G. Woodson D. George W. Carver D. Chicago B. Frederick Douglass and Carter G. Woodson C. Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth 2. From which university did former First 5. Rosa Parks became famous for her D. Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln Lady Michelle Obama graduate? role in inspiring which protest for civil rights? 8. Kamala Harris, United States’ first A. Princeton C. Yale female Vice President, first African- B. Stanford D. Harvard A. Freedom Rides American, and first Asian-American B. Montgomery Bus Boycott Vice President, graduated from 3. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. gave his C. March from Selma to Montgomery Howard University, which is located in famous I Have a Dream speech _________. D. Sit-in Movement ________. A. During a sermon at Ebenezer Baptist Church in 6. The 13th Amendment to the U.S. A. Atlanta Atlanta, Georgia Constitution outlawed slavery in all the B. Queens, N.Y. B. At the swearing-in of President John F. Kennedy United States in __________. C. Washington D.C. D. C. At the end of the march from Selma to Chicago A.