The Alliance for Progress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United States Cold War Policy, the Peace Corps and Its Volunteers in Colombia in the 1960S

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2008 United States Cold War Policy, The Peace Corps And Its Volunteers In Colombia In The 1960s. John James University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation James, John, "United States Cold War Policy, The Peace Corps And Its Volunteers In Colombia In The 1960s." (2008). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 3630. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/3630 UNITED STATES COLD WAR POLICY, THE PEACE CORPS AND ITS VOLUNTEERS IN COLOMBIA IN THE 1960s by J. BRYAN JAMES B.A. Florida State University, 1994 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2008 ABSTRACT John F. Kennedy initiated the Peace Corps in 1961 at the height of the Cold War to provide needed manpower and promote understanding with the underdeveloped world. This study examines Peace Corps work in Colombia during the 1960s within the framework of U.S. Cold War policy. It explores the experiences of volunteers in Colombia and contrasts their accounts with Peace Corps reports and presentations to Congress. -

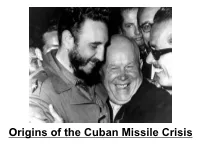

Origins of the Cuban Missile Crisis Kagan’S Thesis “It Is Not Enough for the State That Wishes to Maintain Peace and the Status Quo to Have Superior Power

Origins of the Cuban Missile Crisis Kagan’s Thesis “It is not enough for the state that wishes to maintain peace and the status quo to have superior power. The [Cuban Missile] Crisis came because the more powerful state also had a leader who failed to convince his opponent of his will to use its power for that purpose” (548). Background • 1/1/1959 – Castro deposes Fulgencio Batista – Still speculation as to whether he was Communist (452) • Feb. 1960 – USSR forges diplomatic ties w/ Castro – July – CUB seizes oil refineries b/c they refused to refine USSR crude • US responds by suspending sugar quota, which was 80% of Cuban exports to USà By October, CUB sells sugar to USSR & confiscates nearly $1B USD invested in CUBà • US implements trade embargo • KAGAN: CUB traded one economic subordination for another (453) Response • Ike invokes Monroe Doctrineà NK says it’s dead – Ike threatens missile strikes if CUB is violated – By Sept. 1960, USSR arms arrive in CUB – KAGAN: NK takes opportunity to reject US hegemony in region; akin to putting nukes in HUN 1956 (454) Nikita, Why Cuba? (455-56) • NK is adventuresome & wanted to see Communism spread around the world • Opportunity prevented itself • US had allies & bases close to USSR. Their turn. • KAGAN: NK was a “true believer” & he was genuinely impressed w/ Castro (456) “What can I say, I’m a pretty impressive guy” – Fidel Bay of Pigs Timeline • March 1960 – Ike begins training exiles on CIA advice to overthrow Castro • 1961 – JFK elected & has to live up to campaign rhetoric against Communism he may not have believed in (Arthur Schlesinger qtd. -

Brazil and the Alliance for Progress

BRAZIL AND THE ALLIANCE FOR PROGRESS: US-BRAZILIAN FINANCIAL RELATIONS DURING THE FORMULATION OF JOÃO GOULART‟S THREE-YEAR PLAN (1962)* Felipe Pereira Loureiro Assistant Professor at the Institute of International Relations, University of São Paulo (IRI-USP), Brazil [email protected] Presented for the panel “New Perspectives on Latin America‟s Cold War” at the FLACSO-ISA Joint International Conference, Buenos Aires, 23 to 25 July, 2014 ABSTRACT The paper aims to analyze US-Brazilian financial relations during the formulation of President João Goulart‟s Three-Year Plan (September to December 1962). Brazil was facing severe economic disequilibria in the early 1960s, such as a rising inflation and a balance of payments constrain. The Three-Year Plan sought to tackle these problems without compromising growth and through structural reforms. Although these were the guiding principles of the Alliance for Progress, President John F. Kennedy‟s economic aid program for Latin America, Washington did not offer assistance in adequate conditions and in a sufficient amount for Brazil. The paper argues the causes of the US attitude lay in the period of formulation of the Three-Year Plan, when President Goulart threatened to increase economic links with the Soviet bloc if Washington did not provide aid according to the country‟s needs. As a result, the US hardened its financial approach to entice a change in the political orientation of the Brazilian government. The US tough stand fostered the abandonment of the Three-Year Plan, opening the way for the crisis of Brazil‟s postwar democracy, and for a 21-year military regime in the country. -

July-August 2017

July-August 2017 A Monthly Publication of the U.S. Consulate Krakow Volume VIII. Issue 5. President John F. Kennedy and his son, John Jr., 1963 (AP Photo) In this issue: President John F. Kennedy Zoom in on America The Life of John F. Kennedy John Fitzgerald Kennedy was born in Brookline, Massa- During WWII John applied and was accepted into the na- chusetts, on May 29, 1917 as the second of nine children vy, despite a history of poor health. He was commander of born into the family of Joseph Patrick Kennedy and Rose PT-100, which on August 2, 1943, was hit and sunk by a Fitzgerald Kennedy. John was often called “Jack”. The Japanese destroyer. Despite injuries to his back, an ail- Kennedys had a powerful impact on America. John Ken- ment that would haunt him to the end of his life, Kennedy nedy’s great-grandfather, Patrick Kennedy, emigrated managed to rescue his surviving crew members and was from Ireland to Boston in 1849 and worked as a barrel declared a “hero” by the New York Times. A year later Joe maker. His grandfather, Patrick Joseph (P.J.) Kennedy, was killed on a volunteer mission in Europe when his air- achieved success first in the saloon and liquor-import craft exploded. businesses, and then in banking. His father, Joseph Pat- Joseph Patrick now placed all his hopes on John. In 1946, rick Kennedy, made investments in banking, ship building, John F. Kennedy successfully ran for the same seat in real estate, liquor importing, and motion pictures and be- Congress, which his grandfather held nearly five decades came one of the richest men in America. -

The Kennedy Administration's Alliance for Progress and the Burdens Of

The Kennedy Administration’s Alliance for Progress and the Burdens of the Marshall Plan Christopher Hickman Latin America is irrevocably committed to the quest for modernization.1 The Marshall Plan was, and the Alliance is, a joint enterprise undertaken by a group of nations with a common cultural heritage, a common opposition to communism and a strong community of interest in the specific goals of the program.2 History is more a storehouse of caveats than of patented remedies for the ills of mankind.3 The United States and its Marshall Plan (1948–1952), or European Recovery Program (ERP), helped create sturdy Cold War partners through the economic rebuilding of Europe. The Marshall Plan, even as mere symbol and sign of U.S. commitment, had a crucial role in re-vitalizing war-torn Europe and in capturing the allegiance of prospective allies. Instituting and carrying out the European recovery mea- sures involved, as Dean Acheson put it, “ac- tion in truly heroic mold.”4 The Marshall Plan quickly became, in every way, a paradigmatic “counter-force” George Kennan had requested in his influential July 1947 Foreign Affairs ar- President John F. Kennedy announces the ticle. Few historians would disagree with the Alliance for Progress on March 13, 1961. Christopher Hickman is a visiting assistant professor of history at the University of North Florida. I presented an earlier version of this paper at the 2008 Policy History Conference in St. Louis, Missouri. I appreciate the feedback of panel chair and panel commentator Robert McMahon of The Ohio State University. I also benefited from the kind financial assistance of the John F. -

Tourist-Technicians: Civilian Diplomacy, Tourism, and Development in Cold War Yucatã¡N Katherine Warming Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2018 Tourist-Technicians: Civilian Diplomacy, Tourism, and Development in Cold War Yucatán Katherine Warming Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Warming, Katherine, "Tourist-Technicians: Civilian Diplomacy, Tourism, and Development in Cold War Yucatán" (2018). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 16484. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/16484 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tourist-Technicians: Civilian diplomacy, tourism, and development in Cold War Yucatán by Katherine Warming A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: History Program of Study Committee: Bonar Hernández, Major Professor Michael Christopher Low Amy Erica Smith The student author, whose presentation of the scholarship herein was approved by the program of study committee, is solely responsible for the content of this thesis. The Graduate College will ensure this thesis is globally accessible and will not permit alterations after a degree is conferred. Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2018 Copyright © Katherine Warming, 2018. All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii ABSTRACT iv CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 2. HISTORIOGRAPHY 7 CHAPTER 3. THE POWER OF PEOPLE: EMERGENCE OF THE CIVILIAN 13 PARTNERSHIP MODEL CHAPTER 4. -

The Cuban Missile Crisis

Textbook Twisters: The Cuban Missile Crisis Different countries interpreted the Cuban Missile Crisis in different ways. Select the country of origin for the following textbook accounts. 1. The defeat of the mercenary Brigade at Bay of Pigs made the U.S. think that the only way of crushing the Cuban Revolution was through a direct military intervention. The U.S. immediately embarked on its preparation. As part of their hostile plans, the U.S. considered a self-inflicted aggression in connection with the Guantanamo Naval Base that would allow them to blame Cuba and provide a pretext for invading the island. With this aim, constant provocations took place from the US side of the base: Marines shooting toward Cuban territory, some times for several hours; the murder of a fisherman. The number of violations of Cuba’s airspace and territorial waters increased. In one single day—July 9th, 1962—U.S. planes flew over Cuban territory 12 times. On another occasion they launched rockets against eastern Cuba territory. US pirate boats attacked unites of the Cuban Revolutionary Navy: three Cubans died during one of those attacks; 17 others were lost in another one. Meanwhile, Washington stepped up its pressures on Latin American governments so they unconditionally support US plans against Cuba. It accompanie[d] its pressures with bribes: an assistance program for Latin America, the so-called Alliance for Progress, portrayed as a solution for the region’s problems. In late 1961, Venezuela and Columbia broke diplomatic relations with Cuba; in January 1962, the 8th Consultative Meeting of OAS Foreign Ministers, in Punta del Este, Uruguay, suspended Cuba’s membership in the organization for its “incompatibility with the inter-American system.” Russia Mexico Cuba Caribbean 2. -

Kennedy and the New Frontier

Kennedy, the New Frontier and the Cold War Foreign Policy 1961-1963 John F. Kennedy Kennedy as a Cold Warrior 1.) Controversial views of his father – Joseph P. Kennedy 2.) War hero – elected to Congress 1946 – visited Vietnam in 1951 3.) Senate in 1952 – critic of Truman Administration 4.) Sickness allowed him to avoid a stand on McCarthy 5.) Praised Diem and South Vietnam – member of “American Friends of Vietnam” – called Vietnam “the cornerstone of the Free World in Southeast Asia” 6.) Criticism of French on Algeria Khrushchev and “Wars of National Liberation” Inaugural address YouTube - JFK Inaugural Address 1 of 2 A response to Khrushchev and a picking up of the Cold War challenge But at the same time a desire to negotiate “So let us begin anew -- remembering on both sides that civility is not a sign of weakness, and sincerity is always subject to proof. Let us never negotiate out of fear, but let us never fear to negotiate. “ Best and the Brightest Early Kennedy Policies • 1.) Increase in military spending – more emphasis on conventional warfare and counter-insurgency – creation of the Green Berets • 2.) More attention to the “Third World” – Alliance for progress, the Peace Corps, the Agency for International Development Kennedy – Press conference March 1961 • THE PRESIDENT: I want to make a brief statement about Laos. • It is, I think, important for all Americans to understand this difficult and potentially dangerous problem. In my last conversation with General Eisenhower, the day before the Inauguration, on January 19, we spent more time on this hard matter than on any other thing; and since then it has been steadily before the Administration as the most immediate of the problems that we found upon taking office. -

The Bay of Pigs, Missile Crisis, and Covert War Against Castro

avk L 1, 24 61, 4 tomr ,11,14-41- ca-401, t vid two 122 STEPHEN G. RABE 1A vkd 6 kg vv,h4 Vi 4 4, As such, "the United States chose a policy in the Northeast of coopera• 11 tion with regional elites and justified the policy in terms of a communis- tic threat." The United States had "contributed to the retention of power by the traditional oligarchy" and "destroyed" a Brazilian pro- gram to modernize the political structure of the Northeast.64 The course of United States reform policies in Honduras and Brazil Fixation with Cuba: pointed to a tension between the Administration's talk of middle- class revolution and its search for anti-Communist stability. As Assis- The Bay of Pigs, Missile Crisis, tant Secretary Martin noted to Schlesinger in 1963, the Alliance for Progress contained "major flaws." Its "laudable social goals" encour- and Covert War Against Castro aged political instability, yet their achievement demanded an 8o per- cent private investment "which cannot be attracted amid political THOMAS G. PATERSON instability."65 President Kennedy recognized the problem, noting, near the end of his administration, that the United States would have to learn to live in a "dangerous, untidy world."66 But little in the President's action's or his Administration's policies indicated that the United States was prepared to identify with progressive social revolu- "My God," muttered Richard Helms of the Central Intelligence tions. The Administration and the President, Bowles concluded, Agency, "these Kennedys keep the pressure on about Castro."! An- never "had the real courage to face up to the implications" of the other CIA officer heard it straight from the Kennedy brothers: "Get principles of the Alliance for Progress.67 off your ass about Cuba."2 About a year after John F. -

Moral Masculinity: the Culture of Foreign Relations

MORAL MASCULINITY: THE CULTURE OF FOREIGN RELATIONS DURING THE KENNEDY ADMINISTRATION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jennifer Lynn Walton, B.A., M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Michael J. Hogan, Adviser ___________________________ Professor Peter L. Hahn Adviser Department of History Professor Kevin Boyle Copyright by Jennifer Lynn Walton 2004 ABSTRACT The Kennedy administration of 1961-1963 was an era marked by increasing tension in U.S.-Soviet relations, culminating in the Cuban missile crisis of October 1962. This period provides a snapshot of the culture and politics of the Cold War. During the early 1960s, broader concerns about gender upheaval coincided with an administration that embraced a unique ideology of masculinity. Policymakers at the top levels of the Kennedy administration, including President John F. Kennedy, operated within a cultural framework best described as moral masculinity. Moral masculinity was the set of values or criteria by which Kennedy and his closest foreign policy advisors defined themselves as white American men. Drawing on these criteria justified their claims to power. The values they embraced included heroism, courage, vigor, responsibility, and maturity. Kennedy’s focus on civic virtue, sacrifice, and public service highlights the “moral” aspect of moral masculinity. To members of the Kennedy administration, these were moral virtues and duties and their moral fitness justified their fitness to serve in public office. Five key elements of moral masculinity played an important role in diplomatic crises during the Kennedy administration. -

The Tumultuous Sixties, 1960–1968

CHAPTER 26 The Tumultuous Sixties, 1960–1968 CHAPTER SUMMARY Chapter 26 examines the impact of the tumultuous 1960s on American society. President Kennedy’s policies and actions in the field of foreign policy were shaped by his acceptance of the containment doctrine and his preference for a bold, interventionist foreign policy. In its quest for friends in the Third World and ultimate victory in the Cold War, the Kennedy administration adopted the policy of “nation building” that, through such agencies as the Alliance for Progress and the Peace Corps, would “help developing nations through the early stages of nationhood.” The Kennedy administration also adopted the concept of “counterinsurgency,” which was intended “to defeat revolutionaries who challenged pro-American Third World governments.” Such policies perpetuated an idea that had long been part of American foreign policy: that other people cannot solve their own problems and that the American economic and governmental model can be transferred intact to other societies. Historian William Appleman Williams believed that such thinking led to “the tragedy of American diplomacy,” and historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. refers to it as “a ghastly illusion.” Although Kennedy’s activist approach to foreign policy helped bring the world to the brink of nuclear disaster in the Cuban missile crisis, in the aftermath of that crisis steps were taken by both superpowers that served to lessen tension and hostility between them. However, the arms race accelerated during both the Kennedy and Johnson years, and the United States and the Soviet Union continued to vie for friends in the Third World. Young African Americans, through sit-ins, reinvigorated the civil rights movement. -

Thirteen Days of Terror: an Interview with Syndicate Reporter Charles Bartlett and His Account of the Cuban Missile Crisis

Thirteen Days of Terror: An Interview with Syndicate Reporter Charles Bartlett and His Account of the Cuban Missile Crisis Gavin Hunter Percy Advanced Placement United States History Instructor: Mi'. Alex Haight February 10,2003 OH PER 2003 Percy, ) Gavin ST. ANDREW'S EPISCOPAL SCHOOL lNTER\n[E\\'EE RELEASE FORM: Tapes and Transcripts K W^<. (Cue , do hereby give to the Saint Andrew's Episcopal name of interviewee School all right, title or interest in the tape-recorded interviews conducted by on |>t; V, Z- S /..jf-jA I understand that these name of interviewer-' date(s) interviews will be protected by copyright and deposited in Saint Andrew's Library and Archives for the use of future students, educators and scholars. I also understand that the tapes and transcripts may be used in public presentations including, but not limited to, audio or video documentaries, slide-tape presentations, exhibits, articles or the world wide web at the projects web site www.doingoralhistory.org. This gift does not preclude any use that I myself want to make of the informalion in these transcripts or recordings. The interviewee acknowledges that he/she will receive no remuneration or compensation for either his/her participalion in the interview or for the rights assigned hereunder. CHECK ONE: Tapes and transcripts may be used without restriction y Tapes and transcripts are subject to the attached restrictions (Typed) IMTERVIEWEE: INTERVIEWER: Signature of Interviewee Signature Typed Name Typed Name J Address Address (J \)c ^.^ .-^i^or t-"^ "^*^<:^ 1 Date Date 8804 Postoak Road • Potomac, Maryland 20854 • (301) 983-5200 • Fax: (301) 983-4710 • http://ww\v.saes.org Table of Contents Release Form 2 Statement of Purpose 3 Biography 4 Historical Contextualization 5 Interview Transcription 14 Historical Analysis 33 Appendix 38 Bibliography 44 Percy-3 Statement of Purpose The purpose of this project is to gain a better understanding and comprehension of the Cuban missile crisis though a primary resource.