Interpreting JFK's Inaugural Address

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2013 Winter Newsletter

HHHHHHH LEGACY JOHN F. KENNEDY LIBRARY FOUNDATION Winter | 2013 Freedom 7 Splashes Down at JFK Presidential Library and Museum “I believe this nation should commit itself, to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth.” – President Kennedy, May 25, 1961 he John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum Joined on September 12 by three students from Pinkerton opened a special new installation featuring Freedom 7, Academy, the alma mater of astronaut Alan B. Shepard Jr., Tthe iconic space capsule that U.S. Navy Commander Kennedy Library Director Tom Putnam unveiled Freedom 7, Alan B. Shepard Jr. piloted on the first American-manned stating, “In bringing the Freedom 7 space capsule to our spaceflight. Celebrating American ingenuity and determination, Museum, the Kennedy Library hopes to inspire a new the new exhibit opened on September 12, the 50th anniversary generation of Americans to use science and technology of President Kennedy’s speech at Rice University, where he so for the betterment of our humankind.” eloquently championed America’s manned space efforts: Freedom 7 had been on display at the U.S. Naval “We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the Academy in Annapolis, MD since 1998, on loan from the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are Smithsonian Air and Space Museum. At the request of hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure Caroline Kennedy, Secretary of the Navy Ray Mabus, the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is the U.S. -

Fifty Years Ago This May, John F. Kennedy Molded Cold War Fears Into a Collective Resolve to Achieve the Almost Unthinkable: Land American Astronauts on the Moon

SHOOTING FOR THE MOON Fifty years ago this May, John F. Kennedy molded Cold War fears into a collective resolve to achieve the almost unthinkable: land American astronauts on the moon. In a new book, Professor Emeritus John Logsdon mines the details behind the president’s epochal decision. .ORG S GE A IM NASA Y OF S NASA/COURTE SHOOTING FOR THE MOON Fifty years ago this May, John F. Kennedy molded Cold War fears into a collective resolve to achieve the almost unthinkable: land American astronauts on the moon. In a new book, Professor Emeritus John Logsdon mines the details behind the president’s epochal decision. BY JOHN M. LOGSDON President John F. Kennedy, addressing a joint session of Congress on May 25, 1961, had called for “a great new American enterprise.” n the middle of a July night in 1969, standing The rest, of course, is history: The Eagle landed. Before a TV outside a faceless building along Florida’s eastern audience of half a billion people, Neil Armstrong took “one giant coast, three men in bright white spacesuits strolled leap for mankind,” and Buzz Aldrin emerged soon after, describing by, a few feet from me—on their way to the moon. the moonscape before him as “magnificent desolation.” They climbed into their spacecraft, atop a But the landing at Tranquility Base was not the whole story massive Saturn V rocket, and, a few hours later, of Project Apollo. I with a powerful blast, went roaring into space, the It was the story behind the story that had placed me at weight on their shoulders far more than could be measured Kennedy Space Center that July day. -

John F. Kennedy and Berlin Nicholas Labinski Marquette University

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Master's Theses (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects Evolution of a President: John F. Kennedy and Berlin Nicholas Labinski Marquette University Recommended Citation Labinski, Nicholas, "Evolution of a President: John F. Kennedy and Berlin" (2011). Master's Theses (2009 -). Paper 104. http://epublications.marquette.edu/theses_open/104 EVOLUTION OF A PRESIDENT: JOHN F. KENNEDYAND BERLIN by Nicholas Labinski A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Milwaukee, Wisconsin August 2011 ABSTRACT EVOLUTION OF A PRESIDENT: JOHN F. KENNEDYAND BERLIN Nicholas Labinski Marquette University, 2011 This paper examines John F. Kennedy’s rhetoric concerning the Berlin Crisis (1961-1963). Three major speeches are analyzed: Kennedy’s Radio and Television Report to the American People on the Berlin Crisis , the Address at Rudolph Wilde Platz and the Address at the Free University. The study interrogates the rhetorical strategies implemented by Kennedy in confronting Khrushchev over the explosive situation in Berlin. The paper attempts to answer the following research questions: What is the historical context that helped frame the rhetorical situation Kennedy faced? What rhetorical strategies and tactics did Kennedy employ in these speeches? How might Kennedy's speeches extend our understanding of presidential public address? What is the impact of Kennedy's speeches on U.S. German relations and the development of U.S. and German Policy? What implications might these speeches have for the study and execution of presidential power and international diplomacy? Using a historical-rhetorical methodology that incorporates the historical circumstances surrounding the crisis into the analysis, this examination of Kennedy’s rhetoric reveals his evolution concerning Berlin and his Cold War strategy. -

CIA Files Relating to Heinz Felfe, SS Officer and KGB Spy

CIA Files Relating to Heinz Felfe, SS officer and KGB Spy Norman J. W. Goda Ohio University Heinz Felfe was an officer in Hitler’s SS who after World War II became a KGB penetration agent, infiltrating West German intelligence for an entire decade. He was arrested by the West German authorities in 1961 and tried in 1963 whereupon the broad outlines of his case became public knowledge. Years after his 1969 release to East Germany (in exchange for three West German spies) Felfe also wrote memoirs and in the 1980s, CIA officers involved with the case granted interviews to author Mary Ellen Reese.1 In accordance with the Nazi War Crimes Disclosure Act the CIA has released significant formerly classified material on Felfe, including a massive “Name File” consisting of 1,900 pages; a CIA Damage Assessment of the Felfe case completed in 1963; and a 1969 study of Felfe as an example of a successful KGB penetration agent.2 These files represent the first release of official documents concerning the Felfe case, forty-five years after his arrest. The materials are of great historical significance and add detail to the Felfe case in the following ways: • They show in more detail than ever before how Soviet and Western intelligence alike used former Nazi SS officers during the Cold War years. 1 Heinz Felfe, Im Dienst des Gegners: 10 Jahre Moskaus Mann im BND (Hamburg: Rasch & Röhring, 1986); Mary Ellen Reese, General Reinhard Gehlen: The CIA Connection (Fairfax, VA: George Mason University Press, 1990), pp. 143-71. 2 Name File Felfe, Heinz, 4 vols., National Archives and Records Administration [NARA], Record Group [RG] 263 (Records of the Central Intelligence Agency), CIA Name Files, Second Release, Boxes 22-23; “Felfe, Heinz: Damage Assessment, NARA, RG 263, CIA Subject Files, Second Release, Box 1; “KGB Exploitation of Heinz Felfe: Successful KGB Penetration of a Western Intelligence Service,” March 1969, NARA, RG 263, CIA Subject Files, Second Release, Box 1. -

John F. Kennedy and the New Frontier

DEMOCRATIC AND POPULAR REPUBLIC OF ALGERIA Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research University of Tlemcen Faculty of Letters, Arts and Foreign Languages Department of English Section of English John F. Kennedy And The New Frontier An Extended Essay Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the “Master” Degree in Anglo-Saxon Literature and Civilisation Presented by Supervised by Sabrina BOUKHALFA Dr Yahia ZEGHOUDI Board of Examiners Mr. BENSAFA Abdelkader (President) (University of Tlemcen) Dr. ZEGHOUDI yahia (Supervisor) (University of Tlemcen) Mr. KHELADI Mohammed (Internal Examiner) (University of Tlemcen) 2014/2015 Dedication I would like to dedicate this Extended Essay to my beloved parents, my sisters: Yousra and Yasmine, my little brother Mohamed Abd El-Karim. Acknowledgements Above all, I thank Allah, the almighty for having given me the strength and patience to undertake and complete this work. I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr ZEGHOUDI yahia, for his help, precious advice and patience. I wish to express my respect and gratitude to the honourable members of the jury: Mr. KHELADI Mohammed and Mr. BENSAFA Abdelkader for devoting some of their time and having accepted reading and commenting on this Extended Essay. I would like to express my deepest and great appreciation to all the teachers of the Department of English I would also like to express my appreciation to all my Class mates, namely Miss. BOUSALEH Sawsen for her help and emotional support. Abstract In essence, the present dissertation seeks to highlight President Kennedy’s political career with a particular focus on his domestic and foreign policies. -

United States Cold War Policy, the Peace Corps and Its Volunteers in Colombia in the 1960S

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2008 United States Cold War Policy, The Peace Corps And Its Volunteers In Colombia In The 1960s. John James University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation James, John, "United States Cold War Policy, The Peace Corps And Its Volunteers In Colombia In The 1960s." (2008). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 3630. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/3630 UNITED STATES COLD WAR POLICY, THE PEACE CORPS AND ITS VOLUNTEERS IN COLOMBIA IN THE 1960s by J. BRYAN JAMES B.A. Florida State University, 1994 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2008 ABSTRACT John F. Kennedy initiated the Peace Corps in 1961 at the height of the Cold War to provide needed manpower and promote understanding with the underdeveloped world. This study examines Peace Corps work in Colombia during the 1960s within the framework of U.S. Cold War policy. It explores the experiences of volunteers in Colombia and contrasts their accounts with Peace Corps reports and presentations to Congress. -

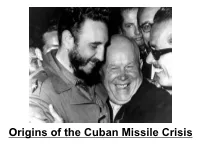

Origins of the Cuban Missile Crisis Kagan’S Thesis “It Is Not Enough for the State That Wishes to Maintain Peace and the Status Quo to Have Superior Power

Origins of the Cuban Missile Crisis Kagan’s Thesis “It is not enough for the state that wishes to maintain peace and the status quo to have superior power. The [Cuban Missile] Crisis came because the more powerful state also had a leader who failed to convince his opponent of his will to use its power for that purpose” (548). Background • 1/1/1959 – Castro deposes Fulgencio Batista – Still speculation as to whether he was Communist (452) • Feb. 1960 – USSR forges diplomatic ties w/ Castro – July – CUB seizes oil refineries b/c they refused to refine USSR crude • US responds by suspending sugar quota, which was 80% of Cuban exports to USà By October, CUB sells sugar to USSR & confiscates nearly $1B USD invested in CUBà • US implements trade embargo • KAGAN: CUB traded one economic subordination for another (453) Response • Ike invokes Monroe Doctrineà NK says it’s dead – Ike threatens missile strikes if CUB is violated – By Sept. 1960, USSR arms arrive in CUB – KAGAN: NK takes opportunity to reject US hegemony in region; akin to putting nukes in HUN 1956 (454) Nikita, Why Cuba? (455-56) • NK is adventuresome & wanted to see Communism spread around the world • Opportunity prevented itself • US had allies & bases close to USSR. Their turn. • KAGAN: NK was a “true believer” & he was genuinely impressed w/ Castro (456) “What can I say, I’m a pretty impressive guy” – Fidel Bay of Pigs Timeline • March 1960 – Ike begins training exiles on CIA advice to overthrow Castro • 1961 – JFK elected & has to live up to campaign rhetoric against Communism he may not have believed in (Arthur Schlesinger qtd. -

COLD WAR, DETENTE & Post- Cold War Scenario

Lecture #01 Political Science COLD WAR, DETENTE & Post- Cold War Scenario For B. A.(Hons.) & M.A. Patliputra University, Patna E-content / Notes by Prof. (Dr.) S. P. Shahi Professor of Political Science & Principal A. N. College, Patna - 800013 Patliputra University, Patna, Bihar E-mail: [email protected] 1 Outline of Lecture Cold War: An Introduction Meaning of Cold War Causes of Cold War DETENTE End of Cold War International Scenario after Cold War Conclusion Cold War: An Introduction After the Second World War, the USA and USSR became two Super Powers. One nation tried to reduce the power of other. Indirectly the competition between the super powers led to the Cold War. It is a type of diplomatic war or ideological war. The Cold War was a period of geopolitical tension or conflict between two superpowers i.e., the United States of America and USSR, after World War-II. 2 The period is generally considered to span the Truman Doctrine (1947) to the dissolution of the Soviet Union (1991), but the first phase of the Cold War began immediately after the end of the Second World War in 1945. The conflict was based around the ideological and geopolitical struggle for global influence by the two powers. United States of America was a representative of Capitalistic ideology and Soviet Union was a representative of Socialist ideology. The United States created the NATO military alliance in 1949 in apprehension of a Soviet attack and termed their global policy against Soviet influence containment. The Soviet Union formed the Warsaw Pact in 1955 in response to NATO. -

Feature Multiple Means to an End: a Reexamination of President Kennedy’S Decision to Go to the Moon by Stephen J

Feature Multiple Means to an End: A Reexamination of President Kennedy’s Decision to Go to the Moon By Stephen J. Garber On May 25, 1961, in his famously special “Urgent National Needs” speech to a joint session of Congress, President John E Kennedy made a dramatic call to send Americans to the Moon “before this decade is out.”’ After this resulted in the highly successful and publicized ApoZZo Program that indeed safely flew humans to the Moon from 1969-1972, historians and space aficio- nados have looked back at Kennedy’s decision in varying ways. Since 1970,2 most social scientists have believed that Kennedy made a single, rational, pragmatic choice to com- CHAT WITH THE AUTHOR pete with the Soviet Union in the arena of space exploration Please join us in a “chat session” with the au- as a way to achieve world prestige during the height of the thor of this article, Stephen J. Garber. In this “chat session,” you may ask Mr. Garber or the Quest Cold War. As such, the drama of space exploration served staff questions about this article, or other ques- simply as a means to an end, not as an goal for its own sake. tions about research and writing the history of Contrary to this approach, some space enthusiasts have spaceflight. The “chat” will be held on Thursday, argued in hindsight that Kennedy pushed the U.S. to explore December 9,7:00CDT. We particularly welcome boldly into space because he was a visionary who saw space Quest subscribers, but anyone may participate. -

Brazil and the Alliance for Progress

BRAZIL AND THE ALLIANCE FOR PROGRESS: US-BRAZILIAN FINANCIAL RELATIONS DURING THE FORMULATION OF JOÃO GOULART‟S THREE-YEAR PLAN (1962)* Felipe Pereira Loureiro Assistant Professor at the Institute of International Relations, University of São Paulo (IRI-USP), Brazil [email protected] Presented for the panel “New Perspectives on Latin America‟s Cold War” at the FLACSO-ISA Joint International Conference, Buenos Aires, 23 to 25 July, 2014 ABSTRACT The paper aims to analyze US-Brazilian financial relations during the formulation of President João Goulart‟s Three-Year Plan (September to December 1962). Brazil was facing severe economic disequilibria in the early 1960s, such as a rising inflation and a balance of payments constrain. The Three-Year Plan sought to tackle these problems without compromising growth and through structural reforms. Although these were the guiding principles of the Alliance for Progress, President John F. Kennedy‟s economic aid program for Latin America, Washington did not offer assistance in adequate conditions and in a sufficient amount for Brazil. The paper argues the causes of the US attitude lay in the period of formulation of the Three-Year Plan, when President Goulart threatened to increase economic links with the Soviet bloc if Washington did not provide aid according to the country‟s needs. As a result, the US hardened its financial approach to entice a change in the political orientation of the Brazilian government. The US tough stand fostered the abandonment of the Three-Year Plan, opening the way for the crisis of Brazil‟s postwar democracy, and for a 21-year military regime in the country. -

Dwight Eisenhower, the Warrior, & John Kennedy, the Cold Warrior

Student Publications Student Scholarship Fall 2014 Dwight Eisenhower, The aW rrior, & John Kennedy, The oldC Warrior: Foreign Policy Under Two Presidents Andrew C. Nosti Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship Part of the American Politics Commons, Defense and Security Studies Commons, European History Commons, Political History Commons, Public Policy Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Nosti, Andrew C., "Dwight Eisenhower, The aW rrior, & John Kennedy, The oC ld Warrior: Foreign Policy Under Two Presidents" (2014). Student Publications. 265. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/265 This is the author's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/ 265 This open access student research paper is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dwight Eisenhower, The aW rrior, & John Kennedy, The oldC Warrior: Foreign Policy Under Two Presidents Abstract This paper presents a comparison between President Eisenhower and President Kennedy's foreign affairs policies, specifically regarding the Cold War, by examining the presidents' interactions with four distinct Cold War regions. Keywords Eisenhower, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Kennedy, John F. Kennedy, Foreign Affairs, Policy, Foreign Policy, Cold War, President Disciplines American Politics | Anthropology | Defense and Security Studies | European History | History | Political History | Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration | Public Policy | Social and Cultural Anthropology | United States History Comments This paper was written for Prof. -

Military Advisors in Vietnam: 1963

Military Advisors in Vietnam: 1963 Topic: Vietnam Grade Level: 9-12 Subject Area: US History after World War II Time Required: 1 class period Goals/Rationale In the winter of 1963, the eyes of most Americans were not on Vietnam. However, Vietnam would soon become a battleground familiar to all Americans. In this lesson plan, students analyze a letter to President Kennedy from a woman who had just lost her brother in South Vietnam and consider Kennedy’s reply, explaining his rationale for sending US military personnel there. Essential Question: What were the origins of US involvement in Vietnam prior to its engagement of combat troops? Objectives Students will: analyze primary sources. discuss US involvement in the Vietnam conflict prior to 1963. evaluate the “domino theory” from the historical perspective of Americans living in 1963. Connections to Curriculum (Standards) National Standards: National Center for History in the Schools Era 9 - Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s), 2B - The student understands United States foreign policy in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America. Era 9, 2C - The student understands the foreign and domestic consequences of US involvement in Vietnam. Massachusetts Frameworks US II.20 – Explain the causes, course and consequences of the Vietnam War and summarize the diplomatic and military policies of Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon. Prior Knowledge Students should have a working knowledge of the Cold War. They should be able to analyze primary sources. Prepared by the Department of Education and Public Programs, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum Historical Background and Context After World War II, the French tried to re-establish their colonial control over Vietnam, the most strategic of the three states comprising the former Indochina (Cambodia, Vietnam and Laos).