Activation of a Paramyxovirus Fusion Protein Is Modulated by Inside-Out Signaling from the Cytoplasmic Tail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete Nucleotide Sequence, Molecular Analysis and Genome Structure of Bacteriophage A118 of Listeria Monocytogenes : Implications for Phage Evolution

Molecular Microbiology (2000) 35(2), 324±340 Complete nucleotide sequence, molecular analysis and genome structure of bacteriophage A118 of Listeria monocytogenes : implications for phage evolution Martin J. Loessner,1* Ross B. Inman,2 Peter Lauer3 local, but sometimes extensive, similarities to a num- and Richard Calendar3 ber of phages spanning a broader phylogenetic range 1Institut fuÈr Mikrobiologie, FML Weihenstephan, of various low GC host bacteria, which implies rela- Technische UniversitaÈtMuÈnchen, Weihenstephaner tively recent exchange of genes or genetic modules. Berg 3, 85350 Freising, Germany. We have also identi®ed the A118 attachment site 2Institute for Molecular Virology, University of attP and the corresponding attB in Listeria monocyto- Wisconsin at Madison, 1525 Linden Drive, Madison, genes, and show that site-speci®c integration of the Wisconsin 53706, USA. A118 prophage by the A118 integrase occurs into a 3Department of Molecular and Cell Biology, host gene homologous to comK of Bacillus subtilis, University of California at Berkeley, 401 Barker Hall, an autoregulatory gene specifying the major compe- Berkeley, California 94720-3202, USA. tence transcription factor. Summary Introduction A118 is a temperate phage isolated from Listeria Listeria monocytogenes is a non-spore-forming, opportu- monocytogenes. In this study, we report the entire nistic Gram-positive pathogen, responsible for severe nucleotide sequence and structural analysis of its infections in both animals and humans, which is almost 40 834 bp DNA. Electron microscopic and enzymatic exclusively transmitted via contaminated food. Recurrent analyses revealed that the A118 genome is a linear, outbreaks of Listeriosis (CDC, 1998; Slutsker and Schuchat, circularly permuted, terminally redundant collection 1999) have emphasized the need for a better understand- of double-stranded DNA molecules. -

Virus Replication Cycles

© Jones and Bartlett Publishers. NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION A scanning electron micrograph of Ebola virus particles. Ebola virus contains an RNA genome. It causes Ebola hemorrhagic fever, which is a severe and often fatal disease in hu- mans and nonhuman primates. CHAPTER Virus Replication Cycles OUTLINE 3.1 One-Step Growth Curves 3.3 The Error-Prone RNA Polymerases: 3 3.2 Key Steps of the Viral Replication Genetic Diversity Cycle 3.4 Targets for Antiviral Therapies In the struggle for survival, the ■ 1. Attachment (Adsorption) ■ RNA Virus Mutagens: A New Class “ ■ 2. Penetration (Entry) of Antiviral Drugs? fi ttest win out at the expense of ■ 3. Uncoating (Disassembly and Virus File 3-1: How Are Cellular Localization) their rivals because they succeed Receptors Used for Viral Attachment ■ 4. Types of Viral Genomes and Discovered? in adapting themselves best to Their Replication their environment. ■ 5. Assembly Refresher: Molecular Biology ” ■ 6. Maturation Charles Darwin ■ 7. Release 46 229329_CH03_046_069.indd9329_CH03_046_069.indd 4466 11/18/08/18/08 33:19:08:19:08 PPMM © Jones and Bartlett Publishers. NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION CASE STUDY The campus day care was recently closed during the peak of the winter fl u season because many of the young children were sick with a lower respiratory tract infection. An email an- nouncement was sent to all students, faculty, and staff at the college that stated the closure was due to a metapneumovirus outbreak. The announcement briefed the campus com- munity with information about human metapneumonoviruses (hMPVs). The announcement stated that hMPV was a newly identifi ed respiratory tract pathogen discovered in the Netherlands in 2001. -

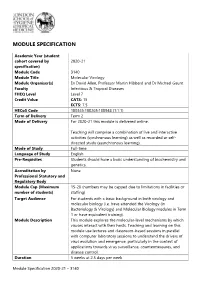

Molecular Virology Module Specification 2020-21

MODULE SPECIFICATION Academic Year (student cohort covered by 2020-21 specification) Module Code 3140 Module Title Molecular Virology Module Organiser(s) Dr David Allen, Professor Martin Hibberd and Dr Michael Gaunt Faculty Infectious & Tropical Diseases FHEQ Level Level 7 Credit Value CATS: 15 ECTS: 7.5 HECoS Code 100345:100265:100948 (1:1:1) Term of Delivery Term 2 Mode of Delivery For 2020-21 this module is delivered online. Teaching will comprise a combination of live and interactive activities (synchronous learning) as well as recorded or self- directed study (asynchronous learning). Mode of Study Full-time Language of Study English Pre-Requisites Students should have a basic understanding of biochemistry and genetics. Accreditation by None Professional Statutory and Regulatory Body Module Cap (Maximum 15-20 (numbers may be capped due to limitations in facilities or number of students) staffing) Target Audience For students with a basic background in both virology and molecular biology (i.e. have attended the Virology (in Bacteriology & Virology) and Molecular Biology modules in Term 1 or have equivalent training). Module Description This module explores the molecular-level mechanisms by which viruses interact with their hosts. Teaching and learning on this module use lectures and classroom-based sessions in parallel with computer laboratory sessions to understand the drivers of virus evolution and emergence, particularly in the context of applications towards virus surveillance, countermeasures, and disease control. Duration 5 weeks -

Paramyxovirus Fusion: Real-Time Measurement of Parainfluenza Virus 5 Virus–Cell Fusion ⁎ Sarah A

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Virology 355 (2006) 203–212 www.elsevier.com/locate/yviro Paramyxovirus fusion: Real-time measurement of parainfluenza virus 5 virus–cell fusion ⁎ Sarah A. Connolly a, Robert A. Lamb a,b, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208-3500, USA b Department of Biochemistry, Molecular Biology, and Cell Biology, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208-3500, USA Received 7 June 2006; returned to author for revision 30 June 2006; accepted 13 July 2006 Available online 17 August 2006 Abstract Although cell–cell fusion assays are useful surrogate methods for studying virus fusion, differences between cell–cell and virus–cell fusion exist. To examine paramyxovirus fusion in real time, we labeled viruses with fluorescent lipid probes and monitored virus–cell fusion by fluorimetry. Two parainfluenza virus 5 (PIV5) isolates (W3A and SER) and PIV5 containing mutations within the fusion protein (F) were studied. Fusion was specific and temperature-dependent. Compared to many low pH-dependent viruses, the kinetics of PIV5 fusion was slow, approaching completion within several minutes. As predicted from cell–cell fusion assays, virus containing an F protein with an extended cytoplasmic tail (rSV5 F551) had reduced fusion compared to wild-type virus (W3A). In contrast, virus–cell fusion for SER occurred at near wild-type levels, despite the fact that this isolate exhibits a severely reduced cell–cell fusion phenotype. These results support the notion that virus–cell and cell– cell fusion have significant differences. © 2006 Elsevier Inc. -

Molecular Virology and Pathogenesis (MICR 812)

Microbiology KU Medical Center Molecular Virology and Pathogenesis (MICR 812) Location of Classes: TBD A. Contact Information Jianming Qiu, Ph.D. 4004 Hixon 588‐4329 [email protected] B. Purpose of this Course This Virology course is aimed at graduate students who pursue master degree in science in the Department of Microbiology. It provides a contemporary understanding of how viruses are built, how they infect and replicate in host cells, how they spread and evolve, how they interact with host cells, how they eventually cause diseases, and how infection of a host can be prevented. This course will provide a balanced approach to Virology, combining the molecular and pathogenesis aspects of Virology. While it is focused primarily on human viruses, it will also discuss animal viruses, as human viruses often are evolved from animal viruses. In addition to traditional topics, this course will explain new “hot” trends in Virology, including: virus‐based vector in human gene therapy; modern advances in vaccinology; “oncolytic” viruses to treat cancers; emerging viruses and potential bioterrorism agents (influenza virus, coronavirus, and filoviruses). C. Intended Course Outcomes By the end of this course, students should be able to: 1. Describe virus taxonomy, virus structure and virus entry, trafficking and egress. 2. Describe the basics of the viral gene expression, including viral replication, transcription, post‐transcriptional regulation, translation and post‐translational regulation of virus genes. 3. Apply techniques used in modern virology and design experiments to test novel hypotheses in virology. 4. Distinguish diverse characteristics of viruses – host range, target tissues, replication strategy, transmission, etc., in particular, of these emerging/reemerging viruses, e.g., influenza and Ebola viruses, and medical important viruses, e.g., HIV. -

Proteomic Approaches to Uncovering Virus–Host Protein Interactions During the Progression of Viral Infection

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Expert Rev Manuscript Author Proteomics. Manuscript Author Author manuscript; available in PMC 2016 June 24. Published in final edited form as: Expert Rev Proteomics. 2016 March ; 13(3): 325–340. doi:10.1586/14789450.2016.1147353. Proteomic approaches to uncovering virus–host protein interactions during the progression of viral infection Krystal K Lum and Ileana M Cristea Department of Molecular Biology, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, USA Abstract The integration of proteomic methods to virology has facilitated a significant breadth of biological insight into mechanisms of virus replication, antiviral host responses and viral subversion of host defenses. Throughout the course of infection, these cellular mechanisms rely heavily on the formation of temporally and spatially regulated virus–host protein–protein interactions. Reviewed here are proteomic-based approaches that have been used to characterize this dynamic virus–host interplay. Specifically discussed are the contribution of integrative mass spectrometry, antibody- based affinity purification of protein complexes, cross-linking and protein array techniques for elucidating complex networks of virus–host protein associations during infection with a diverse range of RNA and DNA viruses. The benefits and limitations of applying proteomic methods to virology are explored, and the contribution of these approaches to important biological discoveries and to inspiring new tractable avenues for the design of antiviral therapeutics is highlighted. Keywords virus–host interactions; mass spectrometry; viral proteomics; AP-MS; IP-MS; interactome Introduction Viruses are fascinatingly diverse in composition, shape, size, tropism, and pathogenesis. Infectious virus particles can have core capsids that can be structurally helical, while others are icosahedral. -

The Molecular Virology of Coronaviruses

REVIEWS The molecular virology of coronaviruses Received for publication, May 26, 2020, and in revised form, July 13, 2020 Published, Papers in Press, July 13, 2020, DOI 10.1074/jbc.REV120.013930 Ella Hartenian1,‡ , Divya Nandakumar2,‡, Azra Lari2 , Michael Ly1, Jessica M. Tucker2, and Britt A. Glaunsinger1,2,3,* From the 1Department of Molecular and Cell Biology, the 2Department of Plant and Microbial Biology, and the 3Howard Hughes Medical Institute, University of California, Berkeley, California, USA Edited by Craig E. Cameron Few human pathogens have been the focus of as much con- In this article, we provide an overview of the coronavirus life centrated worldwide attention as severe acute respiratory syn- cycle with an eye toward its notable molecular features and drome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the cause of COVID-19. Its potential targets for therapeutic interventions (Fig. 1). Much of emergence into the human population and ensuing pandemic the information presented is derived from studies of the beta- came on the heels of severe acute respiratory syndrome corona- coronaviruses MHV, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV, with a rap- virus (SARS-CoV) and Middle East respiratory syndrome coro- idly expanding number of reports on SARS-CoV-2. The first navirus (MERS-CoV), two other highly pathogenic coronavirus portion of the review focuses on the molecular basis of corona- spillovers, which collectively have reshaped our view of a virus virus entry and its replication cycle. We highlight several nota- family previously associated primarily with the common cold. It ble properties, such as the sophisticated viral gene expression has placed intense pressure on the collective scientific commu- and replication strategies that enable maintenance of a remark- nity to develop therapeutics and vaccines, whose engineering ably large, single-stranded, positive-sense (1) RNA genome relies on a detailed understanding of coronavirus biology. -

Umass Molecular Virology Laboratory 2019-Ncov Rrt-PCR Dx Panel

October 1, 2020 Lloyd Hutchinson, Ph.D., FABCC Scientific Director, Laboratory of Diagnostic Molecular Oncology UMass Memorial Medical Center 1 Innovation Drive Three Biotech Rm 276 Worcester, MA 01605 Device: UMass Molecular Virology Laboratory 2019-nCoV rRT-PCR Dx Panel Laboratory: UMass Memorial Medical Center Indication: Qualitative detection of nucleic acid from SARS-CoV-2 in nasal, mid-turbinate nasal, nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal (throat) swab, nasopharyngeal aspirate, and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) specimens from individuals suspected of COVID-19 by a healthcare professional. Testing is limited to the UMass Memorial Medical Center laboratory located in Worcester, MA which is certified under Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA), 42 U.S.C. §263a, and meets requirements to perform high complexity tests. Dear Dr. Hutchinson: This letter is in response to your1 request that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issue an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for emergency use of your product,2 pursuant to Section 564 of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (the Act) (21 U.S.C. §360bbb-3). On February 4, 2020, pursuant to Section 564(b)(1)(C) of the Act, the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) determined that there is a public health emergency that has a significant potential to affect national security or the health and security of United States citizens living abroad, and that involves the virus that causes COVID-19. Pursuant to Section 564 of the Act, and on the basis of such determination, the Secretary of HHS then declared that circumstances exist justifying the authorization of emergency use of in 1 For ease of reference, this letter will use the term “you” and related terms to refer to UMass Memorial Medical Center. -

Introduction to Molecular Virology S

ISSN 20790597, Russian Journal of Genetics: Applied Research, 2014, Vol. 4, No. 4, pp. 325–339. © Pleiades Publishing, Ltd., 2014. Original Russian Text © S.V. Netesov, N.A. Markovich, 2014, published in Vavilovskii Zhurnal Genetiki i Selektsii, 2014, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 22–39. Introduction to Molecular Virology S. V. Netesova, b and N. A. Markovichb aNovosibirsk State University, Novosibirsk, Russia email: [email protected], [email protected] bState Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology Vector, Koltsovo, Novosibirsk oblast, Russia Received February 20, 2014; in final form, February 28, 2014 DOI: 10.1134/S2079059714040078 INTRODUCTION THE ROLE OF VARIOUS PATHOGENS IN THE ETIOLOGY OF DIFFERENT According to the data of the World Health Organi DISEASE TYPES zation (WHO), the share of mortality caused by infec tious and parasitic diseases considerably decreased The diagram in Fig. 3 shows the causes of child gas (approximately, by 15–20%; Fig. 1) versus the moral trointestinal diseases in developing countries ity of cardiovascular and cancer diseases, which (Kapikian, 1993). It is evident that rotaviruses account noticeably increased. Undoubtedly, the expansion of for 45% of such infections; astroviruses, for 7%; cali vaccination in developing and developed countries civiruses and adenoviruses, for 1% each; and the underlies this decrease in infectious and parasitic dis remaining infections are caused by bacteria and yet eases. As for the increase in cardiovascular and cancer unknown pathogens. Thus, viruses cause over 60% of mortalities, this is associated with an increase in the all gastrointestinal diseases in children in developing lifespan, so that people began to attain the age when countries. -

Veterinary Microbiology and Preventive Medicine (V MPM) 1

Veterinary Microbiology and Preventive Medicine (V MPM) 1 V MPM 388: Public Health and the Role of the Veterinary Profession VETERINARY MICROBIOLOGY (3-0) Cr. 3. S. AND PREVENTIVE MEDICINE Prereq: Second-year classification in veterinary medicine Fundamental epidemiology, zoonotic diseases, occupational health, food (V MPM) safety, other public health topics. Any experimental courses offered by V MPM can be found at: V MPM 390: Topics in Veterinary History registrar.iastate.edu/faculty-staff/courses/explistings/ (http:// (1-0) Cr. 1. F.S. www.registrar.iastate.edu/faculty-staff/courses/explistings/) An overview of the history of veterinary medicine focused primarily on disease-specific events. A review of the historical aspects of the Courses primarily for professional curriculum students: veterinary profession's accomplishments in the discovery of the V MPM 360: Global Health etiological origins of disease and their subsequent control will provide (Cross-listed with GLOBE, MICRO). (3-0) Cr. 3. F. students with insights that are applicable to understanding and solving Prereq: BIOL 211 today's animal and human health challenges. Explores human health across the world with particular emphasis V MPM 428: Principles of Epidemiology and Population Health on low- and lower-middle-income countries. Attention is given to the (Dual-listed with V MPM 528). (Cross-listed with MICRO, VDPAM). (3-0) Cr. interconnectedness of health determinants, problems, and solutions 3. S. found in global health, including the role of animals and the environment. Epidemiology of disease in populations. Disease causality, observational Broad in scope, highlighting different cultures and the historical study design and approaches to epidemiologic investigations. -

Nonenveloped Mammalian Reoviruses (Planar Bilayers/Infectious Subviral Particles)

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 90, pp. 10549-10552, November 1993 Microbiology Ion channels induced in lipid bilayers by subvirion particles of the nonenveloped mammalian reoviruses (planar bilayers/infectious subviral particles) MAGDALENA T. TOSTESON*, MAX L. NIBERTtt, AND BERNARD N. FIELDS§ *Laboratory for Membrane Transport, Harvard Medical School, 240 Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115; tDepartment of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics, Harvard Medical School and Department of Pathology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA 02115; and §Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics, Shipley Institute of Medicine, Harvard Medical School and Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA 02115 Contributed by Bernard N. Fields, August 9, 1993 ABSTRACT Mechanisms by which nonenveloped viruses Han reoviruses have a genome comprising 10 unique seg- penetrate cell membranes as an early step in infection are not ments of dsRNA, which encode one or two viral proteins well understood. Current ideas about the mode for cytosolic each and are encased within mature virion particles by two penetration by nonenveloped viruses include (i) formation of a concentric, icosahedrally organized protein capsids. The membrane-spanning pore through which viral components outer capsid proteins ofreoviruses include those that mediate enter the cell and (ii) local breakdown ofthe cellular membrane interactions with cells during the early stages of viral infec- to provide direct access of infecting virus to the cell's interior. tion: -

Molecular Virology By: Joseph Osmundson

COVID-19 Molecular Virology by: Joseph Osmundson Last updated: May 13, 2020 Molecular Virology SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, is a large, single stranded RNA virus in the family of coronaviruses. After emerging in human populations in late 2019, SARS-CoV-2 has spread worldwide leading to millions of infections and hundreds of thousands of deaths. After entering the cell via the host’s ACE2 receptor, SARS-CoV-2 can infect a wide range of cells, including in the patient’s lungs, leading to problems breathing and pneumonia. Shortly after the discovery of COVID-19 cases in China, molecular biologists sequenced the full viral genome, identified the host receptor in cell culture, and described both serology (antibody) and RNA-based (PCR) tests for SARS-CoV-2 infection. These molecular studies of SARS-CoV-2 have been essential for our public health professionals to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. We call for ongoing tight collaboration between public health officials and clinical labs with access to SARS-CoV-2 samples, and academic researchers with molecular virology expertise. Viral RNA Sequencing The SARS-CoV-2 viral replication machinery, like that of other coronaviruses, encodes an error checking domain. Therefore, its mutation rate is slow compared to other RNA viruses, like HIV and influenza. A large-scale, global project sequenced the viral RNA of thousands of samples to determine the number and position of mutations (single nucleotide polymorphisms or SNPs) from the inferred ancestral virus that was present in China in late 2019. A map of viral relatedness, or phylogeny, can then be built that shows the evolutionary trajectory of viral spread.