Are Australia's Cities Outgrowing Its

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Valustrat Dubai Real Estate Review Q1 2019

Real Estate Market 1st Quarter | 2019 Review Real VPI Residential VPI Residential VPI Office Estate Capital Values Rental Values Capital Values Performance -12.4% -9.0% -14.4% Q1 Y-o-Y Q1 Y-o-Y Q1 Y-o-Y Market Intelligence. VPI Simplified. ValuStrat Price Index Source: ValuStrat Source: ValuStrat Source: ValuStrat Key Indicators Source: REIDIN, DTCM, ValuStrat Residential Off-Plan Residential Off-Plan Residential Ready Residential Ready Residential Sales Ticket Size Sales Volume Sales Ticket Size Sales Volume Rents 1.59m 4,418 1.64m 2,677 94,929 AED Transactions AED Transactions AED p.a. 24.6% 4.8% 7.0% -0.9% -1.9% Q-o-Q Q-o-Q Q-o-Q Q-o-Q Q-o-Q Hotel Average Hotel Office Sales Office Sales Office Daily Rate Occupancy Ticket Size Volume Rents 465 78% 1.05m 387 968 AED Jan-Dec 2018 Jan-Dec 2018 AED Transactions AED/sq m p.a. -5.5% 2.0% -17.5% 64.0% -1.0% Y-o-Y Q-o-Q Q-o-Q Q-o-Q Q-o-Q Increase Stable Decline 1 | Dubai Real Estate Market 1st Quarter 2019 Review VPI ValuStrat Price Index Residential The valuation-based ValuStrat Price Index (VPI) for Dubai’s residential capital values, VPI - Dubai Residential Capital Values displayed an overall 12.4% annual fall in 16 Apartment and 10 Villa Locations [Base: Jan 2014=100] capital values, with quarterly declines of 3.2%. This downward trend resulted in 27.1% 110 citywide capital value loss since the peaks of 98.0 97.9 97.5 97.5 97.0 100 96.7 96.2 95.4 mid-2014. -

Case Study Australia 108, Melbourne

Case Study Australia 108, Melbourne CoxGomyl delivers a complete facade access solution for the tallest residential tower in Australia Australia 108 is the tallest residential tower in the Southern Hemisphere by height to the roof, surpassing Eureka Tower and Queensland’s Q1 Tower. The bold and imaginative design by Fender Katsalidis Architects, towers 320 metres and 100 stories over Melbourne’s famous Southbank precinct. Facts & Figures Beyond the sheer scale of the building, the complex aesthetic is inspired by the Commonwealth Star of the Australian flag with a unique golden ‘starburst’ feature projecting out from the slender, curving form of the tower across levels 69 to 72. Commencement 2020 The ambitious scale of the building and its complex geography required the Completion 2020 experience and expertise of CoxGomyl as market leaders in facade access solutions in order to ensure practical, reliable access coverage and safeguard Building Height 320m the well being of the tower for years into the future. The comprehensive building access system developed by the CoxGomyl Floor Count 100 team is made up of five Building Maintenance Units working in harmony to provide all of the required coverage and functionality. The first BMU is No. of BMUs 5 located in a fixed position at roof level which services the area from the top of the building to the bottom of the starburst feature. With a reach of nearly 34 metres and a system of mullion guides which allow operators to manoeuvre Outreach Up to 33.94m the cradle out from the main facade surface, this challenging feature is made conveniently accessible. -

GENESYS 20 Service Manual Table of Contents

GENESYS™ 20 SPECTROPHOTOMETER SERVICE MANUAL GENESYS™ 20 SPECTROPHOTOMETER SERVICE MANUAL Copyright © 1998-2002, Thermo Spectronic All rights reserved. NOTE This service manual contains information, instructions, and specifications for the GENESYS™ 20 spectrophotometer that were believed accurate at the time this manual was written. However, as part of Thermo Spectronic’s on-going program of product development, the specifications and operating instructions may be changed from time to time. Thermo Spectronic reserves the right to change such operating instructions and specifications. Under no circumstances shall Thermo Spectronic be obligated to notify purchasers of any future changes in either this or any other instructions or specifications relating to Thermo Spectronic products, nor shall Thermo Spectronic be liable in any way for its failure to notify purchasers of such changes. FCC COMPLIANCE STATEMENT FOR U.S.A. USERS This equipment generates, uses, and can radiate radio frequency energy, and if not installed and used in accordance with the reference guide, may cause interference to radio communications. It has been tested and found to comply with the limits in effect at the time of manufacture for a Class A computing device pursuant to Subpart J of Part 15 of FCC Rules, which are designed to provide reasonable protection against such interference when operated in a commercial environment. Operation of this equipment in a residential area is likely to cause interference in which case the user at his own expense will be required to take whatever measures may be required to correct the interference. i NEW PRODUCT WARRANTY Thermo Spectronic instrumentation and related accessories are warranted against defects in material and workmanship for a period of three (3) years from the date of delivery. -

Australia: Rising up Down Under 2. Journal Paper Ctbuh.Org/Papers

ctbuh.org/papers Title: Australia: Rising Up Down Under Authors: Subject: Architectural/Design Publication Date: 2017 Original Publication: CTBUH Journal 2017 Issue IV Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat / Tall Buildings in Numbers Australia: Rising Up Down Under Australia is one of the world’s least densely-populated countries, Study of 100m+ Buildings in Australia and yet it has one of the highest proportions of urban dwellers, a 356 Completed; 82 Under Construction; 438 Total figure that is increasing. A boom in tall building construction is underway, paralleled by several significant transportation projects, Government Adelaide 0.7% (3) 0.9% (4) particularly in the three CTBUH 2017 Conference cities of Sydney, Hotel Education Perth Melbourne and Brisbane. This study examines the timeline, 5% (22) 0.2% (1) 5.9% (26) composition, and location of buildings 100 meters and taller (complete or under construction), set against the backdrop of new Mixed-Use Gold Coast 11.4% (50) public transportation projects that are “connecting the city” and 12.1% (53) Melbourne 33.3% (146) aligning towards a denser, more sustainable future. Residential Brisbane 45.4% (199) 16% (70) Note: The six cities in this study are Australia’s six largest in terms of population, and all O ffi c e contain at least one 100-meter or taller building. “City” in this study is identical to a 36.5% (160) “metropolitan area,” as defined by the Australian Bureau of Statistics. -

Tall Buildings in 2020: COVID-19 Contributes to Dip in Year-On-Year Completions

CTBUH Year in Review: Tall Trends of 2020 Tall Buildings in 2020: COVID-19 Contributes To Dip in Year-On-Year Completions Abstract In 2020, the tall building industry constructed 106 buildings of 200 meters’ height or greater, a 20 percent decline from 2019, when 133 such buildings were completed.* The decline can be partly attributed to work stoppages and other impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. This report provides analysis and commentary on global and regional trends underway during an eventful year. Research Project Kindly Sponsored by: Note: Please refer to Tall Buildings in Numbers—The Global Tall Building Picture: Impact of 2020 in conjunction with this Schindler paper, pages 48–49. *The study sets a minimum threshold of 200 meters’ height because of the completeness of data available on buildings of that height. Keywords: Construction, COVID-19, Development, Height, Hotel, Megatall, Mixed-Use, Office, Residential, Supertall Introduction This is the second year in a row in which Center (New York City) completed, that the the completion figure declined. In 2019, tallest building of the year was in the For many people, 2020 will be remembered the reasons for this were varied, though United States. as the year that nothing went to plan. The the change in the tall building climate in same can be said for the tall building China, with public policy statements This is also the first year since 2014 in which industry. As a global pandemic took hold in against needless production of there has not been at least one building the first quarter, numerous projects around exceedingly tall buildings, constituted a taller than 500 meters completed. -

Tall Can Be Beautiful

The Financial Express January 10, 2010 7 INDIA’S VERTICAL QUEST TALLCANBEBEAUTIFUL SCRAPINGTHE PreetiParashar 301m)—willbecompleted. FSI allowed is 1.50-2.75 in all metros and meansprojectswillbecheaperonaunit-to- ronment-friendly. ” KaizerRangwala mid-risebuildings.ThisisbecauseIndian TalltowersshouldbedesignedfortheIndi- SKY, FORWHAT? Of the newer constructions,the APIIC ground coverage is 30-40%. It is insuffi- unit basis and also more plentiful in prof- “There is a need for more service pro- cities have the lowest floor space index an context. They should take advantage of S THE WORLD’S Tower (Andhra Pradesh Industrial Infra- cient to build skyscrapers here.”He adds, itable areas,which is good news for viders of eco-friendly construction mate- Winston Churchill said, (FSI), in the world. Government regula- thelocalclimate—rainfall,light,ventilation, tallest building, the structure Corporation Tower) being built “The maximum height that can be built investors and the buyers.However, allow- rials toreducecosts,”saysPeriwal. “We make our buildings tions thatallowspecific number of build- solar orientation without sacrificing the KiranYadav theleadafterWorldWarI—again,aperiod 828-metreBurjKhalifa, at Hyderabadisexpectedtobea100-storey (basedonperacrescalculation)isapproxi- ing high-rises indiscriminately in certain However Sandhir thinks of high-rises and afterwards they make ing floors based on the land area, thus street-levelorientationof buildings;history; marked by economic growth and techno- alters the skyline of buildingwithaheightof -

Abu Dhabi Report H22012

Abu Dhabi Report H2 2012 “2012 was a pivotal year for the Abu Dhabi real estate market with the delivery of significant new developments which have raised the quality of living and working standards in the capital. The residential sub-sectors are now becoming more clearly defined by qualitative factors with tenants seeking value for money. In 2013 we expect to see a widening segregation in rental rates between the popular new developments, which, with occupancy levels rising, will be able to sustain rental levels and in some cases achieve growth, and the less popular older stock, that will continue to see rents come under downward pressure as landlords compete to maintain occupancy.“ Paul Maisfield, Associate Director & General Manager Abu Dhabi, Asteco Property Management Abu Dhabi Supply Estimates 2012 New Supply 2013 Scheduled New Supply Average Apartment Rental Rates (AED’000/pa) Apartments (in units) 9,000 12,000 Studio 1 BR 2 BR 3 BR Villas (in units) 6,000 5,000 From To From To From To From To Offices (in m2) 312,000 290,000 Marasy -- 87 110 135 170 185 237 Marina Square 55 65 75 85 110 130 140 180 Nation Towers - - 95 100 145 170 165 300 Reef Downtown - - 55 65 70 75 85 95 Residential Market Overview Rihan Heights -- 95 122 130 150 155 190 We estimate that approximately 15,000 new homes have been delivered to the Abu Dhabi market Saadiyat Beach Apartments -- 81 128 130 163 165 206 over the course of 2012, with a further 17,000 scheduled for completion in 2013. -

CTBUH Journal

About the Council The Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat, based at the Illinois Institute of CTBUH Journal Technology in Chicago, is an international International Journal on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat not-for-profi t organization supported by architecture, engineering, planning, development, and construction professionals. Founded in 1969, the Council’s mission is to disseminate multi-disciplinary information on Tall buildings: design, construction, and operation | 2013 Issue III tall buildings and sustainable urban environments, to maximize the international interaction of professionals involved in creating the built environment, and to make the latest Case Study: The Bow, Calgary knowledge available to professionals in a useful form. Debating Tall: Do Trees Belong on Skyscrapers? The CTBUH disseminates its fi ndings, and Imagining the Tall Building of the Future facilitates business exchange, through: the publication of books, monographs, The Use of Stainless Steel in Second-Skin Façades proceedings, and reports; the organization of world congresses, international, regional, and Politics, History, and Height in Warsaw specialty conferences and workshops; the maintaining of an extensive website and tall Using CFD to Optimize Tall Buildings building databases of built, under construction, and proposed buildings; the distribution of a Tall Building in Numbers: Vanity Height monthly international tall building e-newsletter; the maintaining of an Talking Tall: Tall Timber Building international resource center; the bestowing of annual awards for design and construction Special Report: CTBUH 2013 London Conference excellence and individual lifetime achievement; the management of special task forces/ working groups; the hosting of technical forums; and the publication of the CTBUH Journal, a professional journal containing refereed papers written by researchers, scholars, and practicing professionals. -

Cities of the Future

CITIES OF THE FUTURE CITIES OF THE FUTURE Chris Johnson, CEO of Urban Taskforce Australia, discussed the Cities of the Future at the recent API National Conference. VANESSA MITCHELL reports. 019 CITIES OF THE FUTURE SYDNEY NEEDS TO DOUBLE ITS AMOUNT OF HOMES FROM THE CURRENT 1.66 MILLION OVER THE NEXT 40 YEARS he cities of the locate growth around city centres, of tall buildings across the world. future are going to corridors and public transport nodes “Seventy-five stories is the be more urbanised, for a new way of living. We will see tallest building in Sydney currently, with higher density high-rise developments around due to aircraft restrictions, but this living—particularly railway stations and a spreading is changing. Taround public transport hubs. out to areas within walking distance “In New York we are seeing a These sometimes contentious of railway stations. trend towards tall, thin, elegant issues were discussed by Chris “This is already happening; we are buildings, such as 111 West 57th Street Johnson, Chief Executive Officer of seeing towers popping up in various (see image on previous page), which Urban Taskforce Australia, on the final areas that include a mix of residential features one apartment per floor and day of the API National Conference. and commercial offerings. What stands at over 1,400 feet. The top Chris, who is a former NSW needs to happen in the future is a apartment of this development sold Government Architect and former strong integration between transport for US$90 million recently. Executive Director at the NSW networks and the planning system, “Australia 108, featuring 100 Department of Planning, said we will and dialogue between these two areas. -

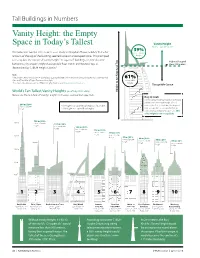

Vanity Height: the Empty Space in Today's Tallest

Tall Buildings in Numbers Vanity Height: the Empty Space in Today’s Tallest Vanity Height Non-occupiable Space 39% We noticed in Journal 2013 Issue I’s case study on Kingdom Tower, Jeddah, that a fair non-occupiable amount of the top of the building seemed to be an unoccupied spire. This prompted height us to explore the notion of “vanity height ” in supertall1 buildings, i.e., the distance Highest Occupied between a skyscraper’s highest occupiable fl oor and its architectural top, as Floor: 198 meters determined by CTBUH Height Criteria.2 Note: 1Historically there have been 74 completed supertalls (300+ m) in the world, including the now-demolished 61% One and Two World Trade Center in New York. occupiable 2 For more information on the CTBUH Height Criteria, visit http://criteria.ctbuh.org height Occupiable Space World’s Ten Tallest Vanity Heights (as of July 2013 data) Top Architectural to Height Below are the ten tallest “Vanity Heights” in today’s completed supertalls. Burj Al Arab With a vanity height of nearly 124 meters within its architectural height of 321 244 m | 29% meters, the Burj Al Arab has the highest non-occupiable * The highest occupied fl oor height as datum line. height ** The highest occupied fl oor height. non-occupiable-to-occupiable height ratio among completed supertalls. 39% of its height is non-occupiable. 133 m | 30% 200 m non-occupiable 131 m | 36% height non-occupiable 124 m | 39% height non-occupiable 113 m | 32% height non-occupiable 99 m | 31% height 150 m non-occupiable height 97 m | 31% 96 m | 29% non-occupiable -

To Read the Full Article CLICK to Download PDF

QUARTERLY REVIEW Issue 3 TALL BUILDINGS Published by Robert Bird Group All rights reserved. 17052018 Making the Most of Tight Spaces Attaining Higher Expectations At Work PNB 118 - Tallest Building in Kuala Lumpur, Fifth Tallest Building in the World Shard - ICE Award Winning Construction Methodology Australia 108 - Tallest Residential Building in the Southern Hemisphere Crown Sydney Dubai’s ICD Brookfield Melbourne’s Southbank Precinct Queensbridge Tower REACHING The Spire London FOR THE SKY Reaching for the Sky Front cover image: Australia 108, Melbourne 2 Inside cover image: The Spire, London From the time of the earliest civilizations, there has been the desire to build the biggest, the tallest of structures. Visions of grandeur, be they in the eyes of kings or corporate giants, have inspired not only architects but also the engineers charged with realizing those visions. “When Robert Bird first started in Brisbane in 1982, a tall building would be 30 storeys,” recalls Robert Bird Group deputy chairman Grant Weir. “Today, it’s more like 50 storeys and up.” That shift in scale has elevated RBG into an exclusive league of structural engineers with the experience, technology and expertise to engineer some of the worlds tallest, best-known modern buildings. Reaching new heights presents new challenges and new standards of quality and safety. Achieving bold iconic designs calls for intense scrutiny of details, aided by modern technology’s ability to virtually build and test these mega-structures through building information modelling. “The higher you go, the more you have to deal with some age-old issues, one of the most significant being the ability to transport workers and materials during construction,” notes Simon Cloherty, director of UK Buildings at RBG. -

AUSTRALIA 108 World Class Global

VIC PROJECT FEATURE AUSTRALIA 108 World Class Global 96 VIC PROJECT FEATURE AUSTRALIA 108 AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL CONSTRUCTION REVIEW WWW.ANCR.COM.AU VIC PROJECT FEATURE AUSTRALIA 108 97 REACH FOR THE SKY DEVELOPER : World Class Global MAIN CONSTRUCTION COMPANY : Multiplex ARCHITECT : Fender Katsalidis PROJECT MANAGER : Sinclair Brook CONSTRUCTION VALUE : $550 million Australia 108 is an incredible landmark $550M skyscraper soaring over 300m high, making it the tallest building in Melbourne and home to the highest apartments in the Southern Hemisphere. The project includes 1,105 luxurious apartments and extensive resident facilities including a 25m lap pool, sauna, steam rooms, gym, private theatre, private dining rooms, virtual golf, infinity edge pool, sky garden, and stunning 360 external views. Rising in the exclusive Southbank district Multiplex introduced new techniques to This exceptional project is a highlight of Melbourne is a new luxury address build Australia 108 including the creation in World Class Global’s catalogue of developed by World Class Global and of purpose built platforms from which developments. “We are so proud of unlike any other in Australia. Standing at builders could install the golden panels of Australia 108 and the outcomes,” said David. 319m tall, Australia 108 will be the tallest the Starburst. An innovative formwork “We are creating an icon on Melbourne’s residential building in Australia, soaring screen system was also used to mitigate skyline which will remain part of the city’s to 100-levels above the city with 1,105 the risk of falling objects over the busy legacy for years to come.” premium apartments and 360 degree views streets below, allowing the façade to be of Melbourne.