On the Problem of Exupérian Heroism in Merleau-Ponty's Phenomenology of Perception

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOYALTY in the WORKS of SAINT-EXUPBRY a Thesis

LOYALTY IN THE WORKS OF SAINT-EXUPBRY ,,"!"' A Thesis Presented to The Department of Foreign Languages The Kansas State Teachers College of Emporia In Partial Fulfillment or the Requirements for the Degree Mastar of Science by "., ......, ~:'4.J..ry ~pp ~·.ay 1967 T 1, f" . '1~ '/ Approved for the Major Department -c Approved for the Graduate Council ~cJ,~/ 255060 \0 ACKNOWLEDGMENT The writer wishes to extend her sincere appreciation to Dr. Minnie M. Miller, head of the foreign language department at the Kansas State Teachers College of Emporia, for her valuable assistance during the writing of this thesis. Special thanks also go to Dr. David E. Travis, of the foreign language department, who read the thesis and offered suggestions. M. E. "Q--=.'Hi" '''"'R ? ..... .-.l.... ....... v~ One of Antoine de Saint-Exupe~J's outstanding qualities was loyalty. Born of a deep sense of responsi bility for his fellowmen and a need for spiritual fellow ship with them it became a motivating force in his life. Most of the acts he is remeffibered for are acts of fidelityo Fis writings too radiate this quality. In deep devotion fo~ a cause or a friend his heroes are spurred on to unusual acts of valor and sacrifice. Saint-Exupery's works also reveal the deep movements of a fervent soul. He believed that to develop spiritually man mQst take a stand and act upon his convictions in the f~c0 of adversity. In his boo~ UnSens ~ la Vie, l he wrote: ~e comprenez-vous Das a~e le don de sol, le risque, ... -

Notions of Self and Nation in French Author

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 6-27-2016 Notions of Self and Nation in French Author- Aviators of World War II: From Myth to Ambivalence Christopher Kean University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Kean, Christopher, "Notions of Self and Nation in French Author-Aviators of World War II: From Myth to Ambivalence" (2016). Doctoral Dissertations. 1161. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1161 Notions of Self and Nation in French Author-Aviators of World War II: From Myth to Ambivalence Christopher Steven Kean, PhD University of Connecticut, 2016 The traditional image of wartime aviators in French culture is an idealized, mythical notion that is inextricably linked with an equally idealized and mythical notion of nationhood. The literary works of three French author-aviators from World War II – Antoine de Saint- Exupéry, Jules Roy, and Romain Gary – reveal an image of the aviator and the writer that operates in a zone between reality and imagination. The purpose of this study is to delineate the elements that make up what I propose is a more complex and even ambivalent image of both individual and nation. Through these three works – Pilote de guerre (Flight to Arras), La Vallée heureuse (The Happy Valley), and La Promesse de l’aube (Promise at Dawn) – this dissertation proposes to uncover not only the figures of individual narratives, but also the figures of “a certain idea of France” during a critical period of that country’s history. -

{PDF EPUB} the Little Prince the Coloring Portfolio by Antoine De Saint-Exupéry the Little Prince

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The Little Prince The Coloring Portfolio by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry The Little Prince. Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article. The Little Prince , French Le Petit Prince , fable and modern classic by French aviator and writer Antoine de Saint-Exupéry that was published with his own illustrations in French as Le Petit Prince in 1943. The simple tale tells the story of a child, the little prince, who travels the universe gaining wisdom. The novella has been translated into hundreds of languages and has sold some 200 million copies worldwide, making it one of the best-selling books in publishing history. Plot summary. The narrator introduces himself as a man who learned when he was a child that adults lack imagination and understanding. He is now a pilot who has crash-landed in a desert. He encounters a small boy who asks him for a drawing of a sheep, and the narrator obliges. The narrator, who calls the child the little prince, learns that the boy comes from a very small planet, which the narrator believes to be asteroid B-612. Over the course of the next few days, the little prince tells the narrator about his life. On his asteroid-planet, which is no bigger than a house, the prince spends his time pulling up baobab seedlings, lest they grow big enough to engulf the tiny planet. One day an anthropomorphic rose grows on the planet, and the prince loves her with all his heart. However, her vanity and demands become too much for the prince, and he leaves. -

Grown-Ups Were Children First. but Few of Them

ark p the of Map opeNING CaLeNDar SeaSoN PASS The best way to enjoy the park all year APRIL MAY round is the season pass. M T w T F S S M T w T F S S 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 chIlD 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 (-1 meter) free 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 chIlD (+1 meter, 27 28 29 30 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 less than 12 years old) 35 € JUNE JULY ADUlT (12 years old and more) 49 € M T w T F S S M T w T F S S 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 5 FAMIly* € 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 99 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 29 30 27 28 29 30 31 ADVANTAGES Unlimited access all year round AUGUST SEPTEMBER -10% discount in the shop M T w T F S S M T w T F S S -10% in the restaurants 1 2 1 2 3 4 5 6 No queue access 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 TIP** 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 28 29 30 The day of your visit, deduct the price of your entrance ticket of the price 31 of the season pass! *Offer valid for a family of 4 persons (2 adults/ 2 children under 17 years old). -

Images of Flight and Aviation and Their Relation to Soviet Identity in Soviet Film 1926-1945

‘Air-mindedness’ and Air Parades: Images of Flight and Aviation and Their Relation to Soviet Identity in Soviet Film 1926-1945 Candyce Veal, UCL PhD Thesis 2 I, Candyce L. Veal, declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 Abstract Taking Soviet films from 1926 to 1945 as its frame of reference, this thesis seeks to answer the question: is autonomous voicing possible in film during a period defined by Stalin’s concentration of power and his authoritarian influence on the arts? Aviation and flight imaging in these films shares characteristics of language, and the examination of the use of aviation and flight as an expressive means reveals nuances in messaging which go beyond the official demand of Soviet Socialist Realism to show life in its revolutionary movement towards socialism. Reviewing the films chronologically, it is shown how they are unified by a metaphor of ‘gaining wings’. In filmic representations of air-shows, Arctic flights, aviation schools, aviation circus-acts, and aircraft invention, the Soviet peoples’ identity in the 1930s became constructed as being metaphorically ‘winged’. This metaphor links to the fundamental Icarian precursor myth and, in turn, speaks to sub-structuring semantic spheres of freedom, transformation, creativity, love and transcendence. Air-parade film communicates symbolically, but refers to real events; like an icon, it visualizes the word of Stalinist- Leninist scriptures. Piloted by heroic ‘falcons’, Soviet destiny was perceived to be a miraculous ‘flight’ which realised the political and technological dreams of centuries. -

An Uneasy Life of a Flying Writer

Title An Uneasy Life of A Flying Writer Author(s) ATARASHI, Toshiharu Citation 北大法学研究科ジュニア・リサーチ・ジャーナル, 8, 329-350 Issue Date 2001-12 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/22334 Type bulletin (article) File Information 8_P329-350.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP An Uneasy Life of A Flying Writer ~m~1'F*O)gPJTO)t:tv)A5t Atarashi Toshiharu Table of Contents I. Introduction .......................................................................... 331 A. Aim of the thesis 331 B. Historical background 331 II. Saint-Exupery and Civil Aviation ........................................... .. 332 A. First flight as a boy .......................................................... .. 333 (1) Moved to Le Mans ........................................................ 333 (2) Baptized to aviation 334 B. Civil pilot license 334 (1) Troubled years 334 (2) Publication of his debut work 335 C. Airmail pilot ....................................................................... 335 (1) Entering Latecoere Company 335 (2) Airfield chief in the desert 336 (3) Return to France 337 (4) To South America 337 (5) Encounter with "Tropical Sheherazade" 338 (6) An internal trouble within the company 338 (7) Night Flight .................................................................... 338 D. Flying journalist/adventurer ............................................... 339 (1) Wasteful life and abortive adventure flight ....................... 339 (2) Another accident in Central America 339 (3) Visit to -

Flight to Arras — a Novel by Antoine De Saint-Exupéry, a a Reading for Enjoyment ARJ2 Review by Bobby Matherne

Flight to Arras — A Novel by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, A A Reading for Enjoyment ARJ2 Review by Bobby Matherne Site Map: MAIN / A Reader's Journal, Vol. 2 Webpage Printer Ready A READER'S JOURNAL Flight to Arras A Novel by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry ARJ2 Chapter: A Reading for Enjoyment Published by Reynal & Hitchcock/NY in 1942 Translated from the French by Lewis Galantière A Book Review by Bobby Matherne ©2009 Arras is a heavy tapestry, especially one hung as a curtain concealing an alcove. "Quick, behind the arras" is a common command in Shakespearean plays to conceal one or more players. Hamlet stabs someone hidden behind an arras. The town, Arras, over which Saint-Exupéry is destined to fly in this story, is where the heavy curtains were first made, and now it appears it will be curtains for Saint- Exupéry, his navigator and gunner, because hardly any planes returned from missions over Arras. There is no safe route to Arras. If one flies high, the German Messerschmidts will come down from above and strafe one's plane to destruction. If one flies lower down, the ack-ack of the anti-craft will tear one's plane to shreds. Any minute Saint-Exupéry will get his orders and be off on a mission from which he does not expect to return, heading behind the curtain of death. He thinks of his old schoolroom, a room much like the one he is waiting in, and then his reverie is broken sharply — the door opens. [page 13, 14] And like a court sentence the words ring out in the quiet schoolroom: "Captain de Saint-Exupéry and Lieutenant Dutertre report to the major!" Schooldays are over. -

Antoine De Saint-Exupéry

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry The Little Prince Translated from French by Iraklis Lampadariou 1 Antoine de Saint-Exupéry (1900-1944) is regarded as one of the most influential authors of France. Important aspects of his life were love, Literature and aviation in which he devoted himself in 1921 when he served his military service in the Air Force. Obtaining a pilot’s license he conducted several flights, getting inspiration for his writings. During the Second World War he wrote “The Little Prince” and he joined the Allied Air Forces. On July 31, 1944, he disappeared with his airplane at Corsica. Just in 2003 the wreck of his airplane was found on the seabed. Bibliography 1926: L'Aviateur (The Aviator) 1929: Courier Sud (Southern Mail) 1931: Vol de Nuit (Night Flight) 1938: Terre de Hommes (Wind, Sand, and Stars) 1942: Pilote de Geurre (Flight to Arras) 1943: Lettre à un Otage (Letter to a Hostage) 1943: Le Petit Prince (The Little Prince) 1948: Citadelle (The Wisdom of the Sands) posthumous 2 Antoine de Saint-Exupéry The Little Prince Translated from French by Iraklis Lampadariou 3 Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, The Little Prince ISBN: 978-618-5147-45-7 July 2015 Τίτλος πρωτοτύπου: Le petit prince Illustrations by: Antoine de Saint-Exupéry Translated from French by: Iraklis Lampadariou, www.lampadariou.eu Page Layout: Konstantina Charlavani, [email protected] Saita Publications Athanasiou Diakou 42 , 65201, Kavala T: 2510831856 M.: 6977 070729 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.saitapublications.gr Based on paragraph 1, Article 29, Law 2121/1993, as amended by paragraph 5, Article 8, Law 2557/1997, “Copyright lasts for the lifetime of the author and seventy (70) years after his death, which are calculated from January 1st of the year after the author’s death.” Bearing in mind that paragraph, we published the translation of the novel “The Little Prince” in English exclusively for readers who are living in Greece. -

MONTEREY BAY 99S LIBRARY Listed in Alphabetical Order by Author

MONTEREY BAY 99S LIBRARY Listed in alphabetical order by Author TITLE AUTHOR PUBLISHER DESCRIPTION On Extended Wings Ackerman, Diane Collier Macmillan 1985 Hard Cover/with dust Jacket Donated by Laura Barnett—January 2009 In this remarkable paean to flying, award- winning poet Diane Ackerman invites us to ride jump seat as she takes—literally and figuratively—to the sky. On Extended Wings tells the story of how she gained mastery over the mysteries of flight and earned her private pilot’s license, of her frustration and exhilaration during hours of lessons and seemingly endless touch-and-go’s, of her first solo and her first cross-country flights, of the teachers and pilots and aviation enthusiasts she befriended and flew with. This book was removed from our library and never returned! The Mercury 13 The Untold Story of Thirteen American Women and the Dream of Space Flight Ackmann, Martha Random House 2003 Hard Cover w/dust jacket Donated by the Estate of Pamela O’Brien—September 2015 A provocative tribute to these extraordinary women, The Mercury 13 is an unforgettable story of determination, resilience, and inextinguishable hope. Father Adams Adams, Nick Tate Publishing & Enterprises, LLC 2014 Soft Cover Autographed Donated by Laura Barnett—August 2014 Father Adams has something for all kinds of readers, and it will be a fast, sometimes turbulent roller coaster ride that ends with a revelation of the human spirit. The characters come alive and invite the reader in the quest of returning home alive. Anyone who has experienced feelings of fear, anger, or exhilaration will have empathy for Father Mike Cross and his cohort, Nick Adams. -

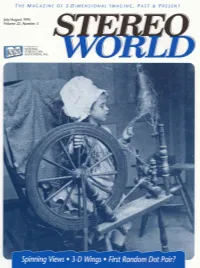

Spinning Views . 3-D Wings First

1 THE MAGAZINE OF 3-DIMENSIONAL IMAGING, PAST 6r PRESENT )uly/August 1995 Volume 22, Number 3 A Publiition d NATIONAL STEREOSCOPIC ASSOCIATION, INC. rn Spinning Views .3-D Wings first Unusual Creations ntries in our "Unusual" assign- ment continue to trickle in EWth table-top scenes compris- ing nearly half of the views. The wide range of what our readers consider unusual has been interest- ing to see. The category may well have been too broad, and perhaps should have been broken into sep- arate assignments like Unusual Images from the Natural World, Unusual People or Events, and Unusual Creations. That might have encouraged more entries in spedfic areas, but meanwhile it's certainly fun going through the wild variety of material now arriv- Land Discovedng Stem at Nine Monthsa by Dovid \I: Vaughn of Cahondak, 4 is a ing. &me to the famous Pdomid Vectogmph of o fly which hecome o popubr eye testing Current Assignment: device for stelemu's. "Unusual" To say this covers a wide range It can be the subject itself that's the confusion! of potential subjects would be an unusual or something about the Deadline for the "Unusual" understatement, to say the least. stereography or the photographic assignment is October 25, 1995. What we would like to see are the processes involved. The unusual can The Rules: stereographs you consider the aspect be a spectacular went, a As space allows (and depending on the most unusual you have wer bizarre subject, an unlikely drcum- response) judges wlll select for publication taken-in whatever sense of the stance, or a humorous situation. -

The Little Prince Director's Notes for School's Educational Package Antoine De Saint Exupéry and the Mysteries of Life How Is I

The Little Prince Director's Notes for School's educational package Antoine de Saint Exupéry and the Mysteries of Life How is it possible for a powerful creature like an elephant to be consumed by a boa constrictor? Antoine St. Exupery answers: the same way as its possible for a powerful adult to be consumed by the necessities, duties and power-plays of everyday life. How easily we confuse the priorities of life and lose our sense of wonder! In terms of keeping the imaginative spirit alive, life is a dangerous business; whether you live on the little prince's imaginary planet where he must clean out three volcanoes daily and uproot life sucking baobab trees, or whether, like the pilot, you fly over the deserts of the world. As the flower says, "the danger is so little understood" that people are often consumed without even knowing it. The Pilot tells us early in the play that understanding the dangers of life's boa constrictors, as a child does vividly, can make a person lonely and misunderstood. We all feel this way at times, and the power of the story is that it can help guide us out of the lonely desert. THE LITTLE PRINCE gives us the story of two very lonely people, a pilot and a fantastical little prince. They have lost the balance between their inner imaginations and the external demands of life , and they have both sought to explore their feelings by flying to other lands. The realities of balance and flight can both be shown by a teeter-totter, and we felt it was so important for audiences to feel them in action that we used one for the set. -

The 15/70 Filmmaker's Manual

The 15/70 Filmmaker’s Manual IMAX Corporation E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.imax.com ©1999 IMAX Corporation - 1 - 1. INTRODUCTION_____________________________________________________________________ 3 2. SOME WORDS YOU SHOULD KNOW: ___________________________________________________ 4 3. ABOUT THE 15/70 FILM FORMAT ______________________________________________________ 5 A. Why make a film in 15/70? __________________________________________________________ 5 B. A few things you ought to know _______________________________________________________ 5 C. Financing and budget considerations___________________________________________________ 6 4. WRITING A 15/70 TREATMENT AND STORYBOARD ______________________________________ 7 5. PRODUCTION CONSIDERATIONS _____________________________________________________ 7 A. The "IMAX Factor" _________________________________________________________________ 8 B. Composition and framing ____________________________________________________________ 8 C. Lens angles and lighting ___________________________________________________________ 10 D. Strobing ________________________________________________________________________ 10 E. Camera noise & run times __________________________________________________________ 10 F. Kinetic good, emetic bad____________________________________________________________ 11 G. Waiting for the weather ____________________________________________________________ 11 H. Smaller shooting ratios _____________________________________________________________ 12 I. Shorter mags