The 15/70 Filmmaker's Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Widescreen Weekend 2007 Brochure

The Widescreen Weekend welcomes all those fans of large format and widescreen films – CinemaScope, VistaVision, 70mm, Cinerama and Imax – and presents an array of past classics from the vaults of the National Media Museum. A weekend to wallow in the best of cinema. HOW THE WEST WAS WON NEW TODD-AO PRINT MAYERLING (70mm) BLACK TIGHTS (70mm) Saturday 17 March THOSE MAGNIFICENT MEN IN THEIR Monday 19 March Sunday 18 March Pictureville Cinema Pictureville Cinema FLYING MACHINES Pictureville Cinema Dir. Terence Young France 1960 130 mins (PG) Dirs. Henry Hathaway, John Ford, George Marshall USA 1962 Dir. Terence Young France/GB 1968 140 mins (PG) Zizi Jeanmaire, Cyd Charisse, Roland Petit, Moira Shearer, 162 mins (U) or How I Flew from London to Paris in 25 hours 11 minutes Omar Sharif, Catherine Deneuve, James Mason, Ava Gardner, Maurice Chevalier Debbie Reynolds, Henry Fonda, James Stewart, Gregory Peck, (70mm) James Robertson Justice, Geneviève Page Carroll Baker, John Wayne, Richard Widmark, George Peppard Sunday 18 March A very rare screening of this 70mm title from 1960. Before Pictureville Cinema It is the last days of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The world is going on to direct Bond films (see our UK premiere of the There are westerns and then there are WESTERNS. How the Dir. Ken Annakin GB 1965 133 mins (U) changing, and Archduke Rudolph (Sharif), the young son of new digital print of From Russia with Love), Terence Young West was Won is something very special on the deep curved Stuart Whitman, Sarah Miles, James Fox, Alberto Sordi, Robert Emperor Franz-Josef (Mason) finds himself desperately looking delivered this French ballet film. -

Thursday 15 October 11:00 an Introduction to Cinerama and Widescreen Cinema 18:00 Opening Night Delegate Reception (Kodak Gallery) 19:00 Oklahoma!

Thursday 15 October 11:00 An Introduction to Cinerama and Widescreen Cinema 18:00 Opening Night Delegate Reception (Kodak Gallery) 19:00 Oklahoma! Please allow 10 minutes for introductions Friday 16 October before all films during Widescreen Weekend. 09.45 Interstellar: Visual Effects for 70mm Filmmaking + Interstellar Intermissions are approximately 15 minutes. 14.45 BKSTS Widescreen Student Film of The Year IMAX SCREENINGS: See Picturehouse 17.00 Holiday In Spain (aka Scent of Mystery) listings for films and screening times in 19.45 Fiddler On The Roof the Museum’s newly refurbished digital IMAX cinema. Saturday 17 October 09.50 A Bridge Too Far 14:30 Screen Talk: Leslie Caron + Gigi 19:30 How The West Was Won Sunday 18 October 09.30 The Best of Cinerama 12.30 Widescreen Aesthetics And New Wave Cinema 14:50 Cineramacana and Todd-AO National Media Museum Pictureville, Bradford, West Yorkshire. BD1 1NQ 18.00 Keynote Speech: Douglas Trumbull – The State of Cinema www.nationalmediamuseum.org.uk/widescreen-weekend 20.00 2001: A Space Odyssey Picturehouse Box Office 0871 902 5756 (calls charged at 13p per minute + your provider’s access charge) 20.00 The Making of The Magnificent Seven with Brian Hannan plus book signing and The Magnificent Seven (Cubby Broccoli) Facebook: widescreenweekend Twitter: @widescreenwknd All screenings and events in Pictureville Cinema unless otherwise stated Widescreen Weekend Since its inception, cinema has been exploring, challenging and Tickets expanding technological boundaries in its continuous quest to provide Tickets for individual screenings and events the most immersive, engaging and entertaining spectacle possible. can be purchased from the Picturehouse box office at the National Media Museum or by We are privileged to have an unrivalled collection of ground-breaking phoning 0871 902 5756. -

Dive 010 - Sea Docs

Dive 010 - Sea Docs Our last collection of Sea Genre films focusing on the watery realms of The Soundtrack Zone may be classified as films in the Sea Documentary genre or, for short, Sea Docs. Two early examples of scores for a Sea Doc film were those composed by Paul J. Smith for two Walt Disney’s True-Life Adventures films: Beaver Valley (1950) and Prowlers of the Everglades (1953). A Disneyland LP (WDL-4011 – released in 1975) included the following tracks from those two films: Beaver Valley (7:15) - Beaver Valley Theme - Baby Ducks - Beaver Romance - Salmon Run – Otters Prowlers of the Everglades (4:09) - Alligators - Swamp Deluge - Otters And Gators LP In 1956, Walt Disney’s Disneyland WDL-4006 LP presented Paul J. Smith’s score for another True-Life Adventure film, Secrets of Life. One of the album’s suites, “Under The Sea And Along The Shore,” includes several underwater-related tracks: Decorator Crab, Jellyfish, Angler Fish, and Fiddler Crabs (04:21) LP Three years later, in 1959, Walt Disney released a short film titled Mysteries of the Deep (23:55). Three of these films – Beaver Valley, Prowlers of the Everglades, and Mysteries of the Deep are available on DVD (see DVD 1 photo below). Secrets of Life is included on DVD 2 (see photo below). DVD 1 DVD 2 Unfortunately none of the scores for these Walt Disney underwater-related films have been commercially issued on CD. Fortunately, the scores of many subsequent Sea Docs films have been released over the years on LP and/or CD. -

L Egends of F Light

L E G E N D S O F F LIGHT LOCKHEED’S SUPER CONSTELLATION Inspired by the Constellation’s Legacy, the Elegance of Air Travel Returns with Boeing’s 787 Dreamliner EL SEGUNDO, Calif. -- The Lockheed Super Constellation, rated by some as the sexiest propeller driven plane, stars in the first-ever 15/70 3D IMAX® film, Legends of Flight. In its heyday, the Super Constellation was as streamlined as the fins on a Cadillac and many times faster. It had all the elegance of a Park Avenue model and the attitude of a B-movie starlet. Above all, the Super Connie epitomized all things American. Even when parked at a ramp it spoke volumes about modern intercontinental flight and the new thrill of flying. This plane brought people to airports just to look and dream. And, how its engines roared! A total of 856 Connies and Super Constellations were built at Lockheed’s Burbank assembly plant, a stone’s throw from the movie studios and perhaps part of the reason this plane looked so good. Four types were built during the production range and each had the distinctive triple-tail design and graceful dolphin fuselage design. What many first-time fliers didn’t know or care about was that the Constellation’s signature wing was effectively the same as that used on the lethal WWII P-38 Lightning. Nor would they know that the triple tail design was actually a move to save money by allowing the plane to fit into existing hangars. It cruised at over 300 MPH while passengers enjoyed sumptuous first-class meals. -

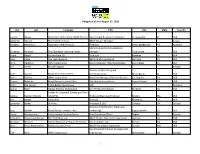

Condensed 8-27-16 Delegate List for Website

Delegate List as of August 27, 2016 First Last Company Title City State Country Lauren Alleva World Golf Hall of Fame IMAX Theater Marketing & Promotions Manager St. Augustine FL USA Abdullah Alshtail The Scientific Center IMAX Theater Manager Kuwait Stephen Amezdroz December Media Pty Ltd Producer South Melbourne VIC Australia Marketing and Communications Christina Amrhein The Challenger Learning Center Manager Tallahassee FL USA Violet Angell Golden Gate 3D Producer Berkeley CA USA John Angle The Tech Museum IMAX Chief Projectionist San Jose CA USA Chris Appleton IMAX Corporation Senior Manager, Aftermarket Sales Los Angeles CA USA Tim Archer Masters Digital Canada Director of Marketing and Katie Baasen McWane Science Center Communications Birmingham AL USA Doris Babiera IMAX Corporation Associate Manager, Film Distribution Los Angeles CA USA Shauna Badheka MacGillivray Freeman Films Distribution Coordinator Laguna Beach CA USA Peter Bak-Larsen Tycho Brahe Planetarium CEO Denmark Janine Baker nWave Pictures Distribution Snr VP Film Distribution Burbank CA USA Center for Science & Society and Twin JoAnna Baldwin Mallory Cities PBS Producer/Executive Producer Boston MA USA Jim Barath Sonics ESD Principal Monterey CA USA Jonathan Barker SK Films President & CEO Toronto ON Canada Director of Distribution Media and Chip Bartlett MacGillivray Freeman Films Technology Laguna Beach CA USA Sandy Baumgartner Saskatchewan Science Centre Chief Executive Officer Regina SK Canada Samantha Belpasso-Robinson The Tech Museum IMAX Theater Operations Supervisor San Jose CA USA Amanda Bennett Denver Museum of Nature & Science Marketing Director Denver CO USA Jenn Bentz Borcherding Pacific Science Center IMAX Projectionist Supervisor Seattle WA USA Vice President Product Development Tod Beric IMAX Corporation Engineering Mississauga ON Canada 1 Delegate List as of August 27, 2016 First Last Company Title City State Country Jonathan Bird Oceanic Research Group, Inc. -

Graeme Ferguson

Ontario Place - home of IMAX Ferguson: It's a film about what it's hke film in Cinesphere? to join the circus, to be a Ferguson: Not for the pubhc. We'll Graeme performer in the circus. The film is pro probably be doing our pre duced and directed by my partner views there. It's the only existing theatre Roman Kroitor, and will probably be Ferguson called "This Way to the Big Show." where we can look at an IMAX film. Ques: Will IMAX be part of all world Ques: Did he use actors in the fUm? — by Shelby M. Gregory and Phyllis Expos to come? Wilson. Ferguson: No, he used only circus per Ferguson: There is an Expo taking place sonnel. Roman took the cam Graeme Ferguson is the Director- in Spokane in 1974, and the era right into the circus, and filmed Cameraman-Producer of "North of United States PaviUon will feature an during actual performances. It was very Superior". He is also president of Multi- IMAX theatre. Screen Corporation Limited, located in difficult because they could only get Gait-Cambridge, Ontario (developers of about two or three shots in any one Ques: Are they paying for the produc IMAX). performance. tion of a film? Ques: Was this filmed with the standard Ferguson: Yes, Paramount Pictures is Ques: What have you been doing since IMAX camera? producing, and Roman and I North of Superior? are involved. Ferguson: Yes, John Spotton was the Ferguson: We're just finishing a film for cameraman. Eldon Rathburn, Ques: Is it a feature film? Ringhng Brothers and Bar- who did the music for Labyrinth, is num and Bailey. -

MARK FREEMAN Encyclopedia of Science, Technology and Society Ooks&Sidtext=0816031231&Leftid=0

MARK FREEMAN Encyclopedia of Science, Technology and Society http://www.factsonfile.com/newfacts/FactsDetail.asp?PageValue=B ooks&SIDText=0816031231&LeftID=0 WIDESCREEN The scale of motion picture projection depends upon the inter- relationship of several factors: the size and aspect ratio of the screen; the gauge of the film; the type of lenses used for filming and projection; and the number of synchronized projectors used. These choices are in turn determined by engineering, marketing and aesthetic considerations. Aspect ratio is the width of the screen divided by the height. The classic standard aspect ratio was expressed as 1.33:1. Today most movies are screened as 1.85:1 or 2.35:1 (widescreen). Films shot in these ratios are cropped for television, which retains the classic ratio of 1.33:1. This cropping is accomplished either by removing a third of the image at the sides of the frame, or by "panning and scanning." In this process a technician determines which portion of a given frame should be included. "Letterboxing" creates a band of black above and below the televised film image. This allows the composition as originally photographed to be screened in video. The larger the film negative, the more resolution. Large film gauges allow greater resolution over a given size of projected image. In the 1890's film sizes varied from 12mm to as many as 80mm, before accepting Edison's 35mm standard. Today films continue to be screened in a variety of guages including Super 8mm, 16mm and Super 16mm, 35mm, 70mm and IMAX. Cinema and the fairground share a common history in the search for technologically based spectacles and attractions. -

9. IMAX Technology and the Tourist Gaze

Charles R. Acland IMAX TECHNOLOGY AND THE TOURIST GAZE Abstract IMAX grew out of the large and multiple screen lm experiments pro- duced for Expo ’67 in Montréal. Since then, it has become the most suc- cessful large format cinema technology.IMAX is a multiple articulation of technological system, corporate entity and cinema practice. This article shows how IMAX is reintroducing a technologically mediated form of ‘tourist gaze’, as elaborated by John Urry,into the context of the insti- tutions of museums and theme parks. IMAX is seen as a powerful exem- plar of the changing role of cinema-going in contemporary post-Fordist culture, revealing new congurations of older cultural forms and practices. In particular,the growth of this brand of commercial cinema runs parallel to a blurring of the realms of social and cultural activity,referred to as a process of ‘dedifferentiation’. This article gives special attention to the espistemological dimensions of IMAX’s conditions of spectatorship. Keywords cinema; epistemology; postmodernism; technology; tourism; spectatorship Technologies and institutional locations of IMAX N E O F T H E rst things you notice at the start of an IMAX lm, after the suspenseful atmosphere created by the mufed acoustics of the theatre, andO after you sink into one of the steeply sloped seats and become aware of the immense screen so close to you, is the clarity of the image. As cinema-goers, we are accustomed to celluloid scratches, to dirty or dim projections, and to oddly ubiquitous focus problems. The IMAX image astonishes with its vibrant colours and ne details. -

Paramount Pictures' 3-D Movie Transformers: Dark of The

PARAMOUNT PICTURES’3 -D MOVIE TRANSFORMERS: DARK OF THE MOON LAUNCHES BACK INTO IMAX® THEATRES FOR EXTENDED TWO-WEEK RUN Film Grosses $1,095 Billion to Date Los Angeles, CA (August 23, 2011) – IMAX Corporation (NYSE:IMAX; TSX:IMX) and Paramount Pictures announced today that Transformers: Dark of the Moon, the third film in the blockbuster Transformers franchise, is returning to 246 IMAX® domestic locations for an extended two-week run from Friday, Aug. 26 through Thursday, Sept. 8. During those two weeks, the 3-D film will play simultaneously with other films in the IMAX network. Since its launch on June 29, Transformers: Dark of the Moon has grossed $1,095 billion globally, with $59.6 million generated from IMAX theatres globally. “The fans have spoken and we are excited to bring Transformers: Dark of the Moon back to IMAX theatres,”said Greg Foster, IMAX Chairman and President of Filmed Entertainment. “The film has been a remarkable success and we are thrilled to offer fans in North America another chance to experience the latest chapter in this history making franchise.”Transformers: Dark of the Moon: An IMAX 3D Experience has been digitally re-mastered into the image and sound quality of The IMAX Experience® with proprietary IMAX DMR® (Digital Re-mastering) technology for presentation in IMAX 3D. The crystal-clear images, coupled with IMAX’s customized theatre geometry and powerful digital audio, create a unique immersive environment that will make audiences feel as if they are in the movie. About Transformers: Dark of the Moon Shia LaBeouf returns as Sam Witwicky in Transformers: Dark of the Moon. -

Spirit Adventure

SPIRITofofof ADVENTURE A MACGILLIVRAY FREEMAN FILM Executive Producers Alvin Townley and Burton Roberts From the Academy Award® nominated producers of EVEREST, the highest-grossing documentary of all time…. …and from the best-selling author of LEGACY OF HONOR…. …comes a motion picture that will reignite a Movement and inspire a nation with Scouting’s SPIRIT OF ADVENTURE. Addressing America’s challenges. As Scouting begins this new century, America needs its programs more than ever – yet too many youth and adults who could benefit from Scouting are not involved. For our country’s sake, Scouting need to reach these individuals. America’s challenges Scouting solutions Personal responsibility Scouts learn to take charge of their lives, make independent choices, and accept responsibility for actions or inactions. Health and fitness Scouting provides the exercise and outdoor activity today’s youth and families need. It develops healthy lifestyle habits. Leadership and motivation Scouting instills leadership skills and personal motivation via goal-oriented training, experiences, and advancement. Broad education Scouting skills and merit badges equip youth with the broad knowledge they need to reach their potential. Character In Scouting, youth find leaders, friends, and communities that instill strong values as they mature into unique individuals. Citizenship and service Scouts adopt principles of collective citizenship, learn about duty to others and our planet, and develop a spirit of service. Mentoring Scouting helps youth build relationships with adults who help them develop into successful young men and women. How can we instill these values in youth and families effectively? Show them Scouting in a new, exciting, and relevant way.. -

Filmography 1963 Through 2018 Greg Macgillivray (Right) with His Friend and Filmmaking Partner of Eleven Years, Jim Freeman in 1976

MacGillivray Freeman Films Filmography 1963 through 2018 Greg MacGillivray (right) with his friend and filmmaking partner of eleven years, Jim Freeman in 1976. The two made their first IMAX Theatre film together, the seminal To Fly!, which premiered at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum on July 1, 1976, one day after Jim’s untimely death in a helicopter crash. “Jim and I cared only that a film be beautiful and expressive, not that it make a lot of money. But in the end the films did make a profit because they were unique, which expanded the audience by a factor of five.” —Greg MacGillivray 2 MacGillivray Freeman Films Filmography Greg MacGillivray: Cinema’s First Billion Dollar Box Office Documentarian he billion dollar box office benchmark was never on Greg MacGillivray’s bucket list, in fact he describes being “a little embarrassed about it,” but even the entertainment industry’s trade journal TDaily Variety found the achievement worth a six-page spread late last summer. As the first documentary filmmaker to earn $1 billion in worldwide ticket sales, giant-screen film producer/director Greg MacGillivray joined an elite club—approximately 100 filmmakers—who have attained this level of success. Daily Variety’s Iain Blair writes, “The film business is full of showy sprinters: filmmakers and movies that flash by as they ring up impressive box office numbers, only to leave little of substance in their wake. Then there are the dedicated long-distance specialists, like Greg MacGillivray, whose thought-provoking documentaries —including EVEREST, TO THE ARCTIC, TO FLY! and THE LIVING Sea—play for years, even decades at a time. -

Estta1050036 04/20/2020 in the United States Patent And

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. http://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA1050036 Filing date: 04/20/2020 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Proceeding 91254173 Party Plaintiff IMAX Corporation Correspondence CHRISTOPHER P BUSSERT Address KILPATRICK TOWNSEND & STOCKTON LLP 1100 PEACHTREE STREET, SUITE 2800 ATLANTA, GA 30309 UNITED STATES [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] 404-815-6500 Submission Motion to Amend Pleading/Amended Pleading Filer's Name Christopher P. Bussert Filer's email [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Signature /Christopher P. Bussert/ Date 04/20/2020 Attachments 2020.04.20 Amended Notice of Opposition for Shenzhen Bao_an PuRuiCai Electronic Firm Limited.pdf(252165 bytes ) IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD In the matter of Application Serial No. 88/622,245; IMAXCAN; Published in the Official Gazette of January 21, 2020 IMAX CORPORATION, ) ) Opposer, ) ) v. ) Opposition No. 91254173 ) SHENZHEN BAO’AN PURUICAI ) ELECTRONIC FIRM LIMITED, ) ) Applicant. ) AMENDED NOTICE OF OPPOSITION Opposer IMAX Corporation (“Opposer”), a Canadian corporation whose business address is 2525 Speakman Drive, Sheridan Science and Technology Park, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada L5K 1B1, believes that it will be damaged by registration of the IMAXCAN mark as currently shown in Application Serial No. 88/622,245 and hereby submits this Amended Notice of Opposition pursuant to 37 C.F.R. §2.107(a) and Fed. R. Civ. P. 15, by which Opposer opposes the same pursuant to the provisions of 15 U.S.C.