Cinerama to Digital Cinema: from the Zenith to the Decline Written by Enric Mas ( ) January 11, 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Widescreen Weekend 2007 Brochure

The Widescreen Weekend welcomes all those fans of large format and widescreen films – CinemaScope, VistaVision, 70mm, Cinerama and Imax – and presents an array of past classics from the vaults of the National Media Museum. A weekend to wallow in the best of cinema. HOW THE WEST WAS WON NEW TODD-AO PRINT MAYERLING (70mm) BLACK TIGHTS (70mm) Saturday 17 March THOSE MAGNIFICENT MEN IN THEIR Monday 19 March Sunday 18 March Pictureville Cinema Pictureville Cinema FLYING MACHINES Pictureville Cinema Dir. Terence Young France 1960 130 mins (PG) Dirs. Henry Hathaway, John Ford, George Marshall USA 1962 Dir. Terence Young France/GB 1968 140 mins (PG) Zizi Jeanmaire, Cyd Charisse, Roland Petit, Moira Shearer, 162 mins (U) or How I Flew from London to Paris in 25 hours 11 minutes Omar Sharif, Catherine Deneuve, James Mason, Ava Gardner, Maurice Chevalier Debbie Reynolds, Henry Fonda, James Stewart, Gregory Peck, (70mm) James Robertson Justice, Geneviève Page Carroll Baker, John Wayne, Richard Widmark, George Peppard Sunday 18 March A very rare screening of this 70mm title from 1960. Before Pictureville Cinema It is the last days of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The world is going on to direct Bond films (see our UK premiere of the There are westerns and then there are WESTERNS. How the Dir. Ken Annakin GB 1965 133 mins (U) changing, and Archduke Rudolph (Sharif), the young son of new digital print of From Russia with Love), Terence Young West was Won is something very special on the deep curved Stuart Whitman, Sarah Miles, James Fox, Alberto Sordi, Robert Emperor Franz-Josef (Mason) finds himself desperately looking delivered this French ballet film. -

Thursday 15 October 11:00 an Introduction to Cinerama and Widescreen Cinema 18:00 Opening Night Delegate Reception (Kodak Gallery) 19:00 Oklahoma!

Thursday 15 October 11:00 An Introduction to Cinerama and Widescreen Cinema 18:00 Opening Night Delegate Reception (Kodak Gallery) 19:00 Oklahoma! Please allow 10 minutes for introductions Friday 16 October before all films during Widescreen Weekend. 09.45 Interstellar: Visual Effects for 70mm Filmmaking + Interstellar Intermissions are approximately 15 minutes. 14.45 BKSTS Widescreen Student Film of The Year IMAX SCREENINGS: See Picturehouse 17.00 Holiday In Spain (aka Scent of Mystery) listings for films and screening times in 19.45 Fiddler On The Roof the Museum’s newly refurbished digital IMAX cinema. Saturday 17 October 09.50 A Bridge Too Far 14:30 Screen Talk: Leslie Caron + Gigi 19:30 How The West Was Won Sunday 18 October 09.30 The Best of Cinerama 12.30 Widescreen Aesthetics And New Wave Cinema 14:50 Cineramacana and Todd-AO National Media Museum Pictureville, Bradford, West Yorkshire. BD1 1NQ 18.00 Keynote Speech: Douglas Trumbull – The State of Cinema www.nationalmediamuseum.org.uk/widescreen-weekend 20.00 2001: A Space Odyssey Picturehouse Box Office 0871 902 5756 (calls charged at 13p per minute + your provider’s access charge) 20.00 The Making of The Magnificent Seven with Brian Hannan plus book signing and The Magnificent Seven (Cubby Broccoli) Facebook: widescreenweekend Twitter: @widescreenwknd All screenings and events in Pictureville Cinema unless otherwise stated Widescreen Weekend Since its inception, cinema has been exploring, challenging and Tickets expanding technological boundaries in its continuous quest to provide Tickets for individual screenings and events the most immersive, engaging and entertaining spectacle possible. can be purchased from the Picturehouse box office at the National Media Museum or by We are privileged to have an unrivalled collection of ground-breaking phoning 0871 902 5756. -

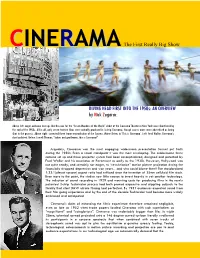

CINERAMA: the First Really Big Show

CCINEN RRAMAM : The First Really Big Show DIVING HEAD FIRST INTO THE 1950s:: AN OVERVIEW by Nick Zegarac Above left: eager audience line ups like this one for the “Seven Wonders of the World” debut at the Cinerama Theater in New York were short lived by the end of the 1950s. All in all, only seven feature films were actually produced in 3-strip Cinerama, though scores more were advertised as being shot in the process. Above right: corrected three frame reproduction of the Cypress Water Skiers in ‘This is Cinerama’. Left: Fred Waller, Cinerama’s chief architect. Below: Lowell Thomas; “ladies and gentlemen, this is Cinerama!” Arguably, Cinerama was the most engaging widescreen presentation format put forth during the 1950s. From a visual standpoint it was the most enveloping. The cumbersome three camera set up and three projector system had been conceptualized, designed and patented by Fred Waller and his associates at Paramount as early as the 1930s. However, Hollywood was not quite ready, and certainly not eager, to “revolutionize” motion picture projection during the financially strapped depression and war years…and who could blame them? The standardized 1:33:1(almost square) aspect ratio had sufficed since the invention of 35mm celluloid film stock. Even more to the point, the studios saw little reason to invest heavily in yet another technology. The induction of sound recording in 1929 and mounting costs for producing films in the newly patented 3-strip Technicolor process had both proved expensive and crippling adjuncts to the fluidity that silent B&W nitrate filming had perfected. -

The Search for Spectators: Vistavision and Technicolor in the Searchers Ruurd Dykstra the University of Western Ontario, [email protected]

Kino: The Western Undergraduate Journal of Film Studies Volume 1 | Issue 1 Article 1 2010 The Search for Spectators: VistaVision and Technicolor in The Searchers Ruurd Dykstra The University of Western Ontario, [email protected] Abstract With the growing popularity of television in the 1950s, theaters experienced a significant drop in audience attendance. Film studios explored new ways to attract audiences back to the theater by making film a more totalizing experience through new technologies such as wide screen and Technicolor. My paper gives a brief analysis of how these new technologies were received by film critics for the theatrical release of The Searchers ( John Ford, 1956) and how Warner Brothers incorporated these new technologies into promotional material of the film. Keywords Technicolor, The Searchers Recommended Citation Dykstra, Ruurd (2010) "The Search for Spectators: VistaVision and Technicolor in The Searchers," Kino: The Western Undergraduate Journal of Film Studies: Vol. 1 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Dykstra: The Search for Spectators The Search for Spectators: VistaVision and Technicolor in The Searchers by Ruurd Dykstra In order to compete with the rising popularity of television, major Hollywood studios lured spectators into the theatres with technical innovations that television did not have - wider screens and brighter colors. Studios spent a small fortune developing new photographic techniques in order to compete with one another; this boom in photographic research resulted in a variety of different film formats being marketed by each studio, each claiming to be superior to the other. Filmmakers and critics alike valued these new formats because they allowed for a bright, clean, crisp image to be projected on a much larger screen - it enhanced the theatre going experience and brought about a re- appreciation for film’s visual aesthetics. -

Square Vs Non-Square Pixels

Square vs non-square pixels Adapted from: Flash + After Effects By Chris Jackson Square vs non square pixels can cause problems when exporting flash for TV and video if you get it wrong. Here Chris Jackson explains how best to avoid these mistakes... Before you adjust the Stage width and height, you need to be aware of the pixel aspect ratio. This refers to the width and height of each pixel that makes up an image. Computer screens display square pixels. Every pixel has an aspect ratio of 1:1. Video uses non-square rectangular pixels, actually scan lines. To make matters even more complicated, the pixel aspect ratio is not consistent between video formats. NTSC video uses a non-square pixel that is taller than it is wide. It has a pixel aspect ratio of 1:0.906. PAL is just the opposite. Its pixels are wider than they are tall with a pixel aspect ratio of 1:1.06. Figure 1: The pixel aspect ratio can produce undesirable image distortion if you do not compensate for the difference between square and non-square pixels. Flash only works in square pixels on your computer screen. As the Flash file migrates to video, the pixel aspect ratio changes from square to non-square. The end result will produce a slightly stretched image on your television screen. On NTSC, round objects will appear flattened. PAL stretches objects making them appear skinny. The solution is to adjust the dimensions of the Flash Stage. A common Flash Stage size used for NTSC video is 720 x 540 which is slightly taller than its video size of 720 x 486 (D1). -

History of Widescreen Aspect Ratios

HISTORY OF WIDESCREEN ASPECT RATIOS ACADEMY FRAME In 1889 Thomas Edison developed an early type of projector called a Kinetograph, which used 35mm film with four perforations on each side. The frame area was an inch wide and three quarters of an inch high, producing a ratio of 1.37:1. 1932 the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences made the Academy Ratio the standard Ratio, and was used in cinemas until 1953 when Paramount Pictures released Shane, produced with a Ratio of 1.66:1 on 35mm film. TELEVISION FRAME The standard analogue television screen ratio today is 1.33:1. The Aspect Ratio is the relationship between the width and height. A Ratio of 1.33:1 or 4:3 means that for every 4 units wide it is 3 units high (4 / 3 = 1.33). In the 1950s, Hollywood's attempt to lure people away from their television sets and back into cinemas led to a battle of screen sizes. Fred CINERAMA Waller of Paramount's Special Effects Department developed a large screen system called Cinerama, which utilised three cameras to record a single image. Three electronically synchronised projectors were used to project an image on a huge screen curved at an angle of 165 degrees, producing an aspect ratio of 2.8:1. This Is Cinerama was the first Cinerama film released in 1952 and was a thrilling travelogue which featured a roller-coaster ride. See Film Formats. In 1956 Metro Goldwyn Mayer was planning a CAMERA 65 ULTRA PANAVISION massive remake of their 1926 silent classic Ben Hur. -

A Brief Intro to Photoshop. Four by Three (4:3): That's For

A brief intro to Photoshop. Although many other image manipulation tools are cheaper and a bit more user friendly, Photoshop is the leading tool for digital image manipulation. As you will see, our uses of Photoshop are basic, but for the introductory student they do require a little bit of work. Please don’t become bogged down in Photoshop. Complete these simple tasks and move on. Four by three (4:3): that’s for me! The industry standard for video and digital video production is an aspect ratio of 4:3. That means the measurements of the screen on which you will see your story finished is 4:3 and we must make all the images you scan fit into that size. The standard measurement for a computer is 640 pixels by 480 pixels (640 x 480 is 4:3!) If an image is scanned or cropped to be a different ratio, then in the end your image will be stretched and distorted to fit the screen, whether you like it or not. Example: You have to put your image through a sizing operation if you want to avoid this distortion. These are your options: 1 Option 1: The Black Bars 1. Open the picture you are working on. Go to FILE > OPEN. Select your file. 2. First make sure that the background is set to black. At the bottom of the tool bar are two little boxes, one on the top left, and one on the bottom right. Click on the bottom left corner box of the COLOR PICKER and choose black in the color picker window. -

MARK FREEMAN Encyclopedia of Science, Technology and Society Ooks&Sidtext=0816031231&Leftid=0

MARK FREEMAN Encyclopedia of Science, Technology and Society http://www.factsonfile.com/newfacts/FactsDetail.asp?PageValue=B ooks&SIDText=0816031231&LeftID=0 WIDESCREEN The scale of motion picture projection depends upon the inter- relationship of several factors: the size and aspect ratio of the screen; the gauge of the film; the type of lenses used for filming and projection; and the number of synchronized projectors used. These choices are in turn determined by engineering, marketing and aesthetic considerations. Aspect ratio is the width of the screen divided by the height. The classic standard aspect ratio was expressed as 1.33:1. Today most movies are screened as 1.85:1 or 2.35:1 (widescreen). Films shot in these ratios are cropped for television, which retains the classic ratio of 1.33:1. This cropping is accomplished either by removing a third of the image at the sides of the frame, or by "panning and scanning." In this process a technician determines which portion of a given frame should be included. "Letterboxing" creates a band of black above and below the televised film image. This allows the composition as originally photographed to be screened in video. The larger the film negative, the more resolution. Large film gauges allow greater resolution over a given size of projected image. In the 1890's film sizes varied from 12mm to as many as 80mm, before accepting Edison's 35mm standard. Today films continue to be screened in a variety of guages including Super 8mm, 16mm and Super 16mm, 35mm, 70mm and IMAX. Cinema and the fairground share a common history in the search for technologically based spectacles and attractions. -

Panaflex Millennium Manual

THE PANAFLEX MILLENNIUM Operations Manual PANAVISION 6219 De Soto Avenue Woodland Hills, CA 818.316.1000 91367 text Nolan Murdock Gary Woods design and production Roger Jennings Richard J. Piedra Susan J. Stone photos Christina Peters © Copyright 2000, Panavision, Inc. Second edition: 09/00 THE PANAFLEX MILLENNIUM Operations Manual Table of Contents SECTION ONE _______________ GENERAL SPECIFICATIONS 1.1 .................................. Cable Specifications 1.2 .................................. Camera Specifications 1.3 .................................. Camera Illustrations 1.4 .................................. Side Camera Views 1.5 .................................. Front and Rear Camera Views 1.6 .................................. Ground Glass Options SECTION TWO ______________ PACKING AND SHIPPING 2.1 .................................. Packing and Transport 2.2 .................................. Accessory Cases SECTION THREE _____________ ASSEMBLY 3.1 .................................. Camera Assembly 3.2 .................................. Digital Display 3.3 .................................. Iris Rod Bracket 3.4 .................................. On-Board Monitor and Bracket 3.5 .................................. Panalens Lite with Video 3.6 .................................. Witness Camera Monitor and Bracket 3.7 .................................. Auxiliary Carrying Handle 3.8 .................................. Follow Focus 3.9 .................................. Eyepiece Option 3.10 ................................ Eyepiece Leveler -

Newsletter 09/07 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 09/07 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 206 - April 2007 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 3 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 09/07 (Nr. 206) April 2007 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, und Fach. Wie versprochen gibt es dar- diesem Editorial auch gar nicht weiter liebe Filmfreunde! in unsere Reportage vom Widescreen aufhalten. Viel Spaß und bis zum näch- Es hat mal wieder ein paar Tage länger Weekend in Bradford. Also Lesestoff sten Mal! gedauert, aber nun haben wir Ausgabe satt. Und damit Sie auch gleich damit 206 unseres Newsletters unter Dach beginnen können, wollen wir Sie mit Ihr LASER HOTLINE Team LASER HOTLINE Seite 2 Newsletter 09/07 (Nr. 206) April 2007 US-Debüt der umtriebigen Pang-Brüder, die alle Register ihres Könnens ziehen, um im Stil von „Amityville Horror“ ein mit einem Fluch belegtes Haus zu Leben zu erwecken. Inhalt Roy und Denise Solomon ziehen mit ihrer Teenager-Tochter Jess und ihrem kleinen Sohn Ben in ein entlegenes Farmhaus in einem Sonnenblumenfeld in North Dakota. Dass sich dort womöglich übernatürliche Dinge abspielen könnten, bleibt von den Erwachsenen unbemerkt. Aber Ben und kurz darauf Jess spüren bald, dass nicht alles mit rechten Dingen zugeht. Weil ihr die Eltern nicht glauben wollen, recherchiert Jess auf eigene Faust und erfährt, dass sich in ihrem neuen Zuhause sechs Jahre zuvor ein bestialischer Mord abgespielt hat. Kritik Für sein amerikanisches Debüt hat sich das umtriebige Brüderpaar Danny und Oxide Pang („The Eye“) eine Variante von „Amityville Horror“ ausgesucht, um eine amerikanische Durchschnittsfamilie nach allen Regeln der Kunst mit übernatürlichem Terror zu überziehen. -

FILM FORMATS ------8 Mm Film Is a Motion Picture Film Format in Which the Filmstrip Is Eight Millimeters Wide

FILM FORMATS ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 8 mm film is a motion picture film format in which the filmstrip is eight millimeters wide. It exists in two main versions: regular or standard 8 mm and Super 8. There are also two other varieties of Super 8 which require different cameras but which produce a final film with the same dimensions. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Standard 8 The standard 8 mm film format was developed by the Eastman Kodak company during the Great Depression and released on the market in 1932 to create a home movie format less expensive than 16 mm. The film spools actually contain a 16 mm film with twice as many perforations along each edge than normal 16 mm film, which is only exposed along half of its width. When the film reaches its end in the takeup spool, the camera is opened and the spools in the camera are flipped and swapped (the design of the spool hole ensures that this happens properly) and the same film is exposed along the side of the film left unexposed on the first loading. During processing, the film is split down the middle, resulting in two lengths of 8 mm film, each with a single row of perforations along one edge, so fitting four times as many frames in the same amount of 16 mm film. Because the spool was reversed after filming on one side to allow filming on the other side the format was sometime called Double 8. The framesize of 8 mm is 4,8 x 3,5 mm and 1 m film contains 264 pictures. -

Panavision Millennium DXL2 Operation Guide

PANAVISION.COM PANAVISION MILLENNIUM DXL2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents 2 Audio During Playback 113 Compliance Statements 4 Timecode, Genlock, Multi-Camera Setup 114 Safety Instructions 6 Timecode 114 Product Introduction 7 Genlock 116 R3D File Format and REDCODE 7 Master/Slave Operation 118 Post Production 7 Set Up Stereo/3D Configuration 122 Camera System Components 8 Camera Array 123 Camera Body 8 Compatible Timecode Devices 123 Media 13 Compatible Genlock Devices 124 DXL Hot Swap Module 14 Upgrade Camera Firmware 125 FIZ Module 21 Verify Current Camera Firmware 125 Lens Mount 21 Upgrade Camera Firmware 125 Additional Components 21 Camera System Maintenance 126 Basic Operations 22 Camera Body and Accessory Exterior Surfaces 126 Power Operations 22 Water Damage 126 Set Up the DXL Hot Swap Module 25 Troubleshoot Your Camera 127 Record 27 General Troubleshooting 127 Basic Menus and User Interface 28 Error Messages 131 GUI Menu Introduction 28 APPENDIX A: Technical Specifications 132 Home Page 29 Panavision Millennium DXL2 132 User Page 31 APPENDIX B: Mechanical Drawings 133 Monitor Page 33 Front View 133 Audio Page 34 Back View 134 Menus Only Accessible Via Home and User Side View (Right) 135 Pages 35 Side View (Left) 136 Detailed Menus 42 Top View 137 Project Settings 42 APPENDIX C: Input/Output Connectors 138 Monitoring 57 USB Power 141 Media Menu 65 DC-IN 141 Look Menu 67 6G/3G HD-SDI 142 User Presets Menu 73 3G HD-SDI 143 Network Menu 80 RETURN 143 Maintenance 86 14V Aux Power Out 144 Playback 104 AUX Power Out 145 Audio System 106 TIMECODE 146 Audio Overview 106 GENLOCK 146 Control 107 GIG-E 147 Monitor Mix 110 LCD/EVF Ports 147 Audio Output 112 14V Aux Power Out 147 Audio Meter (VU Meter) 112 24V Aux Power Out 148 COPYRIGHT © 2020 PAN AVISION INTERNATIONAL, L.P.