9. IMAX Technology and the Tourist Gaze

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Widescreen Weekend 2007 Brochure

The Widescreen Weekend welcomes all those fans of large format and widescreen films – CinemaScope, VistaVision, 70mm, Cinerama and Imax – and presents an array of past classics from the vaults of the National Media Museum. A weekend to wallow in the best of cinema. HOW THE WEST WAS WON NEW TODD-AO PRINT MAYERLING (70mm) BLACK TIGHTS (70mm) Saturday 17 March THOSE MAGNIFICENT MEN IN THEIR Monday 19 March Sunday 18 March Pictureville Cinema Pictureville Cinema FLYING MACHINES Pictureville Cinema Dir. Terence Young France 1960 130 mins (PG) Dirs. Henry Hathaway, John Ford, George Marshall USA 1962 Dir. Terence Young France/GB 1968 140 mins (PG) Zizi Jeanmaire, Cyd Charisse, Roland Petit, Moira Shearer, 162 mins (U) or How I Flew from London to Paris in 25 hours 11 minutes Omar Sharif, Catherine Deneuve, James Mason, Ava Gardner, Maurice Chevalier Debbie Reynolds, Henry Fonda, James Stewart, Gregory Peck, (70mm) James Robertson Justice, Geneviève Page Carroll Baker, John Wayne, Richard Widmark, George Peppard Sunday 18 March A very rare screening of this 70mm title from 1960. Before Pictureville Cinema It is the last days of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The world is going on to direct Bond films (see our UK premiere of the There are westerns and then there are WESTERNS. How the Dir. Ken Annakin GB 1965 133 mins (U) changing, and Archduke Rudolph (Sharif), the young son of new digital print of From Russia with Love), Terence Young West was Won is something very special on the deep curved Stuart Whitman, Sarah Miles, James Fox, Alberto Sordi, Robert Emperor Franz-Josef (Mason) finds himself desperately looking delivered this French ballet film. -

CINERAMA: the First Really Big Show

CCINEN RRAMAM : The First Really Big Show DIVING HEAD FIRST INTO THE 1950s:: AN OVERVIEW by Nick Zegarac Above left: eager audience line ups like this one for the “Seven Wonders of the World” debut at the Cinerama Theater in New York were short lived by the end of the 1950s. All in all, only seven feature films were actually produced in 3-strip Cinerama, though scores more were advertised as being shot in the process. Above right: corrected three frame reproduction of the Cypress Water Skiers in ‘This is Cinerama’. Left: Fred Waller, Cinerama’s chief architect. Below: Lowell Thomas; “ladies and gentlemen, this is Cinerama!” Arguably, Cinerama was the most engaging widescreen presentation format put forth during the 1950s. From a visual standpoint it was the most enveloping. The cumbersome three camera set up and three projector system had been conceptualized, designed and patented by Fred Waller and his associates at Paramount as early as the 1930s. However, Hollywood was not quite ready, and certainly not eager, to “revolutionize” motion picture projection during the financially strapped depression and war years…and who could blame them? The standardized 1:33:1(almost square) aspect ratio had sufficed since the invention of 35mm celluloid film stock. Even more to the point, the studios saw little reason to invest heavily in yet another technology. The induction of sound recording in 1929 and mounting costs for producing films in the newly patented 3-strip Technicolor process had both proved expensive and crippling adjuncts to the fluidity that silent B&W nitrate filming had perfected. -

The Search for Spectators: Vistavision and Technicolor in the Searchers Ruurd Dykstra the University of Western Ontario, [email protected]

Kino: The Western Undergraduate Journal of Film Studies Volume 1 | Issue 1 Article 1 2010 The Search for Spectators: VistaVision and Technicolor in The Searchers Ruurd Dykstra The University of Western Ontario, [email protected] Abstract With the growing popularity of television in the 1950s, theaters experienced a significant drop in audience attendance. Film studios explored new ways to attract audiences back to the theater by making film a more totalizing experience through new technologies such as wide screen and Technicolor. My paper gives a brief analysis of how these new technologies were received by film critics for the theatrical release of The Searchers ( John Ford, 1956) and how Warner Brothers incorporated these new technologies into promotional material of the film. Keywords Technicolor, The Searchers Recommended Citation Dykstra, Ruurd (2010) "The Search for Spectators: VistaVision and Technicolor in The Searchers," Kino: The Western Undergraduate Journal of Film Studies: Vol. 1 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Dykstra: The Search for Spectators The Search for Spectators: VistaVision and Technicolor in The Searchers by Ruurd Dykstra In order to compete with the rising popularity of television, major Hollywood studios lured spectators into the theatres with technical innovations that television did not have - wider screens and brighter colors. Studios spent a small fortune developing new photographic techniques in order to compete with one another; this boom in photographic research resulted in a variety of different film formats being marketed by each studio, each claiming to be superior to the other. Filmmakers and critics alike valued these new formats because they allowed for a bright, clean, crisp image to be projected on a much larger screen - it enhanced the theatre going experience and brought about a re- appreciation for film’s visual aesthetics. -

History of Widescreen Aspect Ratios

HISTORY OF WIDESCREEN ASPECT RATIOS ACADEMY FRAME In 1889 Thomas Edison developed an early type of projector called a Kinetograph, which used 35mm film with four perforations on each side. The frame area was an inch wide and three quarters of an inch high, producing a ratio of 1.37:1. 1932 the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences made the Academy Ratio the standard Ratio, and was used in cinemas until 1953 when Paramount Pictures released Shane, produced with a Ratio of 1.66:1 on 35mm film. TELEVISION FRAME The standard analogue television screen ratio today is 1.33:1. The Aspect Ratio is the relationship between the width and height. A Ratio of 1.33:1 or 4:3 means that for every 4 units wide it is 3 units high (4 / 3 = 1.33). In the 1950s, Hollywood's attempt to lure people away from their television sets and back into cinemas led to a battle of screen sizes. Fred CINERAMA Waller of Paramount's Special Effects Department developed a large screen system called Cinerama, which utilised three cameras to record a single image. Three electronically synchronised projectors were used to project an image on a huge screen curved at an angle of 165 degrees, producing an aspect ratio of 2.8:1. This Is Cinerama was the first Cinerama film released in 1952 and was a thrilling travelogue which featured a roller-coaster ride. See Film Formats. In 1956 Metro Goldwyn Mayer was planning a CAMERA 65 ULTRA PANAVISION massive remake of their 1926 silent classic Ben Hur. -

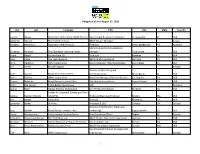

Condensed 8-27-16 Delegate List for Website

Delegate List as of August 27, 2016 First Last Company Title City State Country Lauren Alleva World Golf Hall of Fame IMAX Theater Marketing & Promotions Manager St. Augustine FL USA Abdullah Alshtail The Scientific Center IMAX Theater Manager Kuwait Stephen Amezdroz December Media Pty Ltd Producer South Melbourne VIC Australia Marketing and Communications Christina Amrhein The Challenger Learning Center Manager Tallahassee FL USA Violet Angell Golden Gate 3D Producer Berkeley CA USA John Angle The Tech Museum IMAX Chief Projectionist San Jose CA USA Chris Appleton IMAX Corporation Senior Manager, Aftermarket Sales Los Angeles CA USA Tim Archer Masters Digital Canada Director of Marketing and Katie Baasen McWane Science Center Communications Birmingham AL USA Doris Babiera IMAX Corporation Associate Manager, Film Distribution Los Angeles CA USA Shauna Badheka MacGillivray Freeman Films Distribution Coordinator Laguna Beach CA USA Peter Bak-Larsen Tycho Brahe Planetarium CEO Denmark Janine Baker nWave Pictures Distribution Snr VP Film Distribution Burbank CA USA Center for Science & Society and Twin JoAnna Baldwin Mallory Cities PBS Producer/Executive Producer Boston MA USA Jim Barath Sonics ESD Principal Monterey CA USA Jonathan Barker SK Films President & CEO Toronto ON Canada Director of Distribution Media and Chip Bartlett MacGillivray Freeman Films Technology Laguna Beach CA USA Sandy Baumgartner Saskatchewan Science Centre Chief Executive Officer Regina SK Canada Samantha Belpasso-Robinson The Tech Museum IMAX Theater Operations Supervisor San Jose CA USA Amanda Bennett Denver Museum of Nature & Science Marketing Director Denver CO USA Jenn Bentz Borcherding Pacific Science Center IMAX Projectionist Supervisor Seattle WA USA Vice President Product Development Tod Beric IMAX Corporation Engineering Mississauga ON Canada 1 Delegate List as of August 27, 2016 First Last Company Title City State Country Jonathan Bird Oceanic Research Group, Inc. -

Graeme Ferguson

Ontario Place - home of IMAX Ferguson: It's a film about what it's hke film in Cinesphere? to join the circus, to be a Ferguson: Not for the pubhc. We'll Graeme performer in the circus. The film is pro probably be doing our pre duced and directed by my partner views there. It's the only existing theatre Roman Kroitor, and will probably be Ferguson called "This Way to the Big Show." where we can look at an IMAX film. Ques: Will IMAX be part of all world Ques: Did he use actors in the fUm? — by Shelby M. Gregory and Phyllis Expos to come? Wilson. Ferguson: No, he used only circus per Ferguson: There is an Expo taking place sonnel. Roman took the cam Graeme Ferguson is the Director- in Spokane in 1974, and the era right into the circus, and filmed Cameraman-Producer of "North of United States PaviUon will feature an during actual performances. It was very Superior". He is also president of Multi- IMAX theatre. Screen Corporation Limited, located in difficult because they could only get Gait-Cambridge, Ontario (developers of about two or three shots in any one Ques: Are they paying for the produc IMAX). performance. tion of a film? Ques: Was this filmed with the standard Ferguson: Yes, Paramount Pictures is Ques: What have you been doing since IMAX camera? producing, and Roman and I North of Superior? are involved. Ferguson: Yes, John Spotton was the Ferguson: We're just finishing a film for cameraman. Eldon Rathburn, Ques: Is it a feature film? Ringhng Brothers and Bar- who did the music for Labyrinth, is num and Bailey. -

MARK FREEMAN Encyclopedia of Science, Technology and Society Ooks&Sidtext=0816031231&Leftid=0

MARK FREEMAN Encyclopedia of Science, Technology and Society http://www.factsonfile.com/newfacts/FactsDetail.asp?PageValue=B ooks&SIDText=0816031231&LeftID=0 WIDESCREEN The scale of motion picture projection depends upon the inter- relationship of several factors: the size and aspect ratio of the screen; the gauge of the film; the type of lenses used for filming and projection; and the number of synchronized projectors used. These choices are in turn determined by engineering, marketing and aesthetic considerations. Aspect ratio is the width of the screen divided by the height. The classic standard aspect ratio was expressed as 1.33:1. Today most movies are screened as 1.85:1 or 2.35:1 (widescreen). Films shot in these ratios are cropped for television, which retains the classic ratio of 1.33:1. This cropping is accomplished either by removing a third of the image at the sides of the frame, or by "panning and scanning." In this process a technician determines which portion of a given frame should be included. "Letterboxing" creates a band of black above and below the televised film image. This allows the composition as originally photographed to be screened in video. The larger the film negative, the more resolution. Large film gauges allow greater resolution over a given size of projected image. In the 1890's film sizes varied from 12mm to as many as 80mm, before accepting Edison's 35mm standard. Today films continue to be screened in a variety of guages including Super 8mm, 16mm and Super 16mm, 35mm, 70mm and IMAX. Cinema and the fairground share a common history in the search for technologically based spectacles and attractions. -

FILM FORMATS ------8 Mm Film Is a Motion Picture Film Format in Which the Filmstrip Is Eight Millimeters Wide

FILM FORMATS ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 8 mm film is a motion picture film format in which the filmstrip is eight millimeters wide. It exists in two main versions: regular or standard 8 mm and Super 8. There are also two other varieties of Super 8 which require different cameras but which produce a final film with the same dimensions. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Standard 8 The standard 8 mm film format was developed by the Eastman Kodak company during the Great Depression and released on the market in 1932 to create a home movie format less expensive than 16 mm. The film spools actually contain a 16 mm film with twice as many perforations along each edge than normal 16 mm film, which is only exposed along half of its width. When the film reaches its end in the takeup spool, the camera is opened and the spools in the camera are flipped and swapped (the design of the spool hole ensures that this happens properly) and the same film is exposed along the side of the film left unexposed on the first loading. During processing, the film is split down the middle, resulting in two lengths of 8 mm film, each with a single row of perforations along one edge, so fitting four times as many frames in the same amount of 16 mm film. Because the spool was reversed after filming on one side to allow filming on the other side the format was sometime called Double 8. The framesize of 8 mm is 4,8 x 3,5 mm and 1 m film contains 264 pictures. -

Paramount Pictures' 3-D Movie Transformers: Dark of The

PARAMOUNT PICTURES’3 -D MOVIE TRANSFORMERS: DARK OF THE MOON LAUNCHES BACK INTO IMAX® THEATRES FOR EXTENDED TWO-WEEK RUN Film Grosses $1,095 Billion to Date Los Angeles, CA (August 23, 2011) – IMAX Corporation (NYSE:IMAX; TSX:IMX) and Paramount Pictures announced today that Transformers: Dark of the Moon, the third film in the blockbuster Transformers franchise, is returning to 246 IMAX® domestic locations for an extended two-week run from Friday, Aug. 26 through Thursday, Sept. 8. During those two weeks, the 3-D film will play simultaneously with other films in the IMAX network. Since its launch on June 29, Transformers: Dark of the Moon has grossed $1,095 billion globally, with $59.6 million generated from IMAX theatres globally. “The fans have spoken and we are excited to bring Transformers: Dark of the Moon back to IMAX theatres,”said Greg Foster, IMAX Chairman and President of Filmed Entertainment. “The film has been a remarkable success and we are thrilled to offer fans in North America another chance to experience the latest chapter in this history making franchise.”Transformers: Dark of the Moon: An IMAX 3D Experience has been digitally re-mastered into the image and sound quality of The IMAX Experience® with proprietary IMAX DMR® (Digital Re-mastering) technology for presentation in IMAX 3D. The crystal-clear images, coupled with IMAX’s customized theatre geometry and powerful digital audio, create a unique immersive environment that will make audiences feel as if they are in the movie. About Transformers: Dark of the Moon Shia LaBeouf returns as Sam Witwicky in Transformers: Dark of the Moon. -

DCI and OTHER Film Formats by Peter R Swinson (November 2005)

DCI and OTHER Film Formats By Peter R Swinson (November 2005) This document attempts to explain some of the isssues facing compliance with the DCI specification for producing Digital Cinema Distribution Masters (DCDM) when the source material is of an aspect ratio different to the two 2K and 4K DCDM containers. Background Early Digital Projection of varying Aspect Ratios. Digital Cinema Projectors comprise image display devices of a fixed aspect ratio. Early Digital Cinema projectors utilised non linear (Anamorphic) optics as a means to provide conversion from one aspect ratio to another, the projectors also generated images using less than the full surface area of the image display devices to provide other aspect ratios, and, on occasions, the combination of both. Film Aspect Ratios Since the inception of Film many aspect ratios have been used. For Feature Films, the film image width has remained nominally constant at what is known as the academy width and the aspect ratio has been determined by the height of the image on the film. One additional aspect is obtained using the same academy width but also using a 2:1 non-linear anamorphic lens to compress the horizontal image 2:1 while filming. A complimentary expanding 2:1 anamorphic lens is used in the cinema. This anamorphic usage ensures that the film’s full image height and width is used to retain quality. This is known generally as Cinemascope with an aspect ratio of 2.39:1. For those who carry out film area measurements against aspect ratios, this number is arrived at by using a slightly greater frame height than regular 35mm film. -

P+S Technik Cinemascope Zoom Lenses

P+S Technik CinemaScope Zoom Lenses CinemaScope The impressive look of a CinemaScope image for the audience is based on the more natural 1:2.35 aspect ratio. Anamorphic cylindrical lens with different compression • Anamorphic 2.0x • Anamorphic 1.5x • Anamorphic 1.33x Digital CinemaScope In the history of Cinema the three different anamorphic powers were used. The 2.0x anamorphic was historically successful because the 4perf 35mm film standard was strong in image capturing and image projection (see below TECHNIRAMA). The 2.0x anamorphic was designed to make good images out of the 4:3 aspect ratio of the 4perf film. The optic design for a 2.0x anamorphic lens was difficult and the performance of these lenses is far from what is expected from a good lens. But this compromise had worked for years. In the middle of the 90 th the Film grain got better and better and consequently the Spherical Optic became really good. The powerful Post Production tools could not use the anamorphic work flow and even India moved out of the anamorphic CinemaScope world. - 1 - Now in the main stream of digital capturing the parameter changed. But funny enough the CinemaScope 2.0x as a comprise of the analog Film times was simple shifted in the Digital world. 1.5x anamorphic lens versus 1.33x and 2.0x From different views a 1.5x anamorphic lens is optimal for the digital cinematography use. • The 1.5 squeeze factor give a great specific anamorphic look. Stronger than 1.33x, but with less problems than with 2.0x based on an optical design who does not eliminate this look. -

Northern Conference Film and Video Guide on Native and Northern Justice Issues

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 287 653 RC 016 466 TITLE Northern Conference Film and Video Guide on Native and Northern Justice Issues. INSTITUTION Simon Fraser Univ., Burnaby (British Columbia). REPORT NO ISBN-0-86491-051-7 PUB DATE 85 NOTE 247p.; Prepared by the Northern Conference Resource Centre. AVAILABLE FROM Northern Conference Film Guide, Continuing Studies, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada V5A 1S6 ($25.00 Canadian, $18.00 U.S. Currency). PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Adolescent Development; *American Indians; *Canada Natives; Children; Civil Rights; Community Services; Correctional Rehabilitation; Cultural Differences; *Cultural Education; *Delinquency; Drug Abuse; Economic Development; Eskimo Aleut Languages; Family Life; Family Programs; *Films; French; Government Role; Juvenile Courts; Legal Aid; Minority Groups; Slides; Social Problems; Suicide; Tribal Sovereignty; Tribes; Videotape Recordings; Young Adults; Youth; *Youth Problems; Youth Programs IDENTIFIERS Canada ABSTRACT Intended for teacheLs and practitioners, this film and video guide contains 235 entries pertaining to the administration of justice, culture and lifestyle, am: education and services in northern Canada, it is divided into eight sections: Native lifestyle (97 items); economic development (28), rights and self-government (20); education and training (14); criminal justice system (26); family services (19); youth and children (10); and alcohol and drug abuse/suicide (21). Each entry includes: title, responsible person or organization, name and address of distributor, date (1960-1984), format (16mm film, videotape, slide-tape, etc.), presence of accompanying support materials, length, sound and color information, language (predominantly English, some also French and Inuit), rental/purchase fees and preview availability, suggested use, and a brief description.