Broken Arrow Volume 2008 , Issue 6 December 5, 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Language of Narrative Drawing: a Close Reading of Contemporary Graphic Novels

The Language of Narrative Drawing: a close reading of contemporary graphic novels Abstract: The study offers an alternative analytical framework for thinking about the contemporary graphic novel as a dynamic area of visual art practice. Graphic narratives are placed within the broad, open-ended territory of investigative drawing, rather than restricted to a special category of literature, as is more usually the case. The analysis considers how narrative ideas and energies are carried across specific examples of work graphically. Using analogies taken from recent academic debate around translation, aspects of Performance Studies, and, finally, common categories borrowed from linguistic grammar, the discussion identifies subtle varieties of creative processing within a range of drawn stories. The study is practice-based in that the questions that it investigates were first provoked by the activity of drawing. It sustains a dominant interest in practice throughout, pursuing aspects of graphic processing as its primary focus. Chapter 1 applies recent ideas from Translation Studies to graphic narrative, arguing for a more expansive understanding of how process brings about creative evolutions and refines directing ideas. Chapter 2 considers the body as an area of core content for narrative drawing. A consideration of elements of Performance Studies stimulates a reconfiguration of the role of the figure in graphic stories, and selected artists are revisited for the physical qualities of their narrative strategies. Chapter 3 develops the grammatical concept of tense to provide a central analogy for analysing graphic language. The chapter adapts the idea of the graphic „confection‟ to the territory of drawing to offer a fresh system of analysis and a potential new tool for teaching. -

Furry by Sean Mcgann © 2019, RN

Furry By Sean McGann © 2019, RN: PAu 3-960-188 [email protected] or [email protected] OPEN TO: BLACK. TAILS (V.O.) It rained heavily that morning. EXT. WINDSHIELD OF TAILS’ TRUCK - MORNING Rain falls upon a truck's windshield. TAILS, a teenage boy with dark brown hair, drives the truck. He wears a purple jacket with a dark blue T-shirt underneath. He has an irritated look in his eyes, and breathes quite heavily. TAILS (V.O.) I woke up at 6:35, and had to use the small amount of driver's ed knowledge that somehow got me a driver’s license to rush to school. Dad drove Mom to work, which meant I would be home alone till about 5:30 after school. For reasons I’ll get into later, I was nothing short of ecstatic. CUT TO: BLACK. CAPTION: A BOATS AGAINST THE CURRENT PRODUCTION CAPTION: A SEAN MCGANN FILM CUT TO: EXT. SCHOOL PARKING LOT - MORNING Tails parks his truck. CAPTION: FURRY INT. HIGH SCHOOL - MORNING Tails walks into school, disheveled and carrying a backpack. He walks through the front entrance, around a corner, up some stairs and through two corridors. TAILS (V.O.) My name is Miles Steadman, but (MORE) (CONTINUED) 2. CONTINUED: (2) TAILS (CONT'D) everyone called me Tails, if anyone ever talked to me. To be perfectly honest, I think I gave myself that dumbass nickname because I was a hardcore Sonic the Hedgehog fanboy back in middle school, when it was acceptable. A Dr. Pepper Sonic lover, as Dave the Bastard once put it. -

Comic Book Collection

2008 preview: fre comic book day 1 3x3 Eyes:Curse of the Gesu 1 76 1 76 4 76 2 76 3 Action Comics 694/40 Action Comics 687 Action Comics 4 Action Comics 7 Advent Rising: Rock the Planet 1 Aftertime: Warrior Nun Dei 1 Agents of Atlas 3 All-New X-Men 2 All-Star Superman 1 amaze ink peepshow 1 Ame-Comi Girls 4 Ame-Comi Girls 2 Ame-Comi Girls 3 Ame-Comi Girls 6 Ame-Comi Girls 8 Ame-Comi Girls 4 Amethyst: Princess of Gemworld 9 Angel and the Ape 1 Angel and the Ape 2 Ant 9 Arak, Son of Thunder 27 Arak, Son of Thunder 33 Arak, Son of Thunder 26 Arana 4 Arana: The Heart of the Spider 1 Arana: The Heart of the Spider 5 Archer & Armstrong 20 Archer & Armstrong 15 Aria 1 Aria 3 Aria 2 Arrow Anthology 1 Arrowsmith 4 Arrowsmith 3 Ascension 11 Ashen Victor 3 Astonish Comics (FCBD) Asylum 6 Asylum 5 Asylum 3 Asylum 11 Asylum 1 Athena Inc. The Beginning 1 Atlas 1 Atomic Toybox 1 Atomika 1 Atomika 3 Atomika 4 Atomika 2 Avengers Academy: Fear Itself 18 Avengers: Unplugged 6 Avengers: Unplugged 4 Azrael 4 Azrael 2 Azrael 2 Badrock and Company 3 Badrock and Company 4 Badrock and Company 5 Bastard Samurai 1 Batman: Shadow of the Bat 27 Batman: Shadow of the Bat 28 Batman:Shadow of the Bat 30 Big Bruisers 1 Bionicle 22 Bionicle 20 Black Terror 2 Blade of the Immortal 3 Blade of the Immortal unknown Bleeding Cool (FCBD) Bloodfire 9 bloodfire 9 Bloodshot 2 Bloodshot 4 Bloodshot 31 bloodshot 9 bloodshot 4 bloodshot 6 bloodshot 15 Brath 13 Brath 12 Brath 14 Brigade 13 Captain Marvel: Time Flies 4 Caravan Kidd 2 Caravan Kidd 1 Cat Claw 1 catfight 1 Children of -

View of the Colony Itself (Being on the Top Floor of the Security Building Has Its Rewards, If Only That One Reward Was a Nice Sunset Every Now and Again)

The Bright Garden by Alex Puncekar Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts in the Northeast Ohio Master of Fine Arts Program YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY May, 2017 The Bright Garden Alex Puncekar I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: Alex Puncekar, Student Date Approvals: Christopher Barzak, Thesis Advisor Date Imad Rahman, Committee Member Date Eric Wasserman, Committee Member Date Dr. Salvatore A. Sanders, Dean of Graduate Studies Date ABSTRACT Calli Hayford lives on Kipos, a recently colonized planet far from Earth. Amongst the jungles and ravenous animals that threaten the various settlements across the planet’s surface, Calli is dealing with something much more dire: her sick mother, who is slowly dying from an unknown sickness. With funds scarce, Calli decides to do the impossible: to locate auracite, a rare mineral native to Kipos, in the hopes that it will provide her with the money to afford a cure. She leaves home with her friend, the sly and scruffy Sera, and encounters a whole new world outside of her own, one that will force her to answer questions she never knew she needed to answer: how far is she willing to go for someone she loves? iii Table of Contents Prologue 1 Chapter 1 6 Chapter 2 21 Chapter 3 35 Chapter 4 57 Chapter 5 80 Chapter 6 92 Chapter 7 123 Chapter 8 136 Chapter 9 156 Chapter 10 165 Chapter 11 192 Chapter 12 220 Chapter 13 245 Chapter 14 260 Chapter 15 279 Chapter 16 296 Chapter 17 313 Chapter 18 333 Chapter 19 358 Chapter 20 374 Chapter 21 387 iv Chapter 22 397 Epilogue 403 v Prologue Diana Hayford remembers Autumn. -

Justice League: Origins

JUSTICE LEAGUE: ORIGINS Written by Chad Handley [email protected] EXT. PARK - DAY An idyllic American park from our Rockwellian past. A pick- up truck pulls up onto a nearby gravel lot. INT. PICK-UP TRUCK - DAY MARTHA KENT (30s) stalls the engine. Her young son, CLARK, (7) apprehensively peeks out at the park from just under the window. MARTHA KENT Go on, Clark. Scoot. CLARK Can’t I go with you? MARTHA KENT No, you may not. A woman is entitled to shop on her own once in a blue moon. And it’s high time you made friends your own age. Clark watches a group of bigger, rowdier boys play baseball on a diamond in the park. CLARK They won’t like me. MARTHA KENT How will you know unless you try? Go on. I’ll be back before you know it. EXT. PARK - BASEBALL DIAMOND - MOMENTS LATER Clark watches the other kids play from afar - too scared to approach. He is about to give up when a fly ball plops on the ground at his feet. He stares at it, unsure of what to do. BIG KID 1 (yelling) Yo, kid. Little help? Clark picks up the ball. Unsure he can throw the distance, he hesitates. Rolls the ball over instead. It stops halfway to Big Kid 1, who rolls his eyes, runs over and picks it up. 2. BIG KID 1 (CONT’D) Nice throw. The other kids laugh at him. Humiliated, Clark puts his hands in his pockets and walks away. Big Kid 2 advances on Big Kid 1; takes the ball away from him. -

THE COLLECTED POEMS of HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam

1 THE COLLECTED POEMS OF HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam 2 PREFACE With the exception of a relatively small number of pieces, Ibsen’s copious output as a poet has been little regarded, even in Norway. The English-reading public has been denied access to the whole corpus. That is regrettable, because in it can be traced interesting developments, in style, material and ideas related to the later prose works, and there are several poems, witty, moving, thought provoking, that are attractive in their own right. The earliest poems, written in Grimstad, where Ibsen worked as an assistant to the local apothecary, are what one would expect of a novice. Resignation, Doubt and Hope, Moonlight Voyage on the Sea are, as their titles suggest, exercises in the conventional, introverted melancholy of the unrecognised young poet. Moonlight Mood, To the Star express a yearning for the typically ethereal, unattainable beloved. In The Giant Oak and To Hungary Ibsen exhorts Norway and Hungary to resist the actual and immediate threat of Prussian aggression, but does so in the entirely conventional imagery of the heroic Viking past. From early on, however, signs begin to appear of a more personal and immediate engagement with real life. There is, for instance, a telling juxtaposition of two poems, each of them inspired by a female visitation. It is Over is undeviatingly an exercise in romantic glamour: the poet, wandering by moonlight mid the ruins of a great palace, is visited by the wraith of the noble lady once its occupant; whereupon the ruins are restored to their old splendour. -

Smallville Download Season 9

Smallville download season 9 TV Series Smallville season 9 Download at High Speed! Full Show episodes get FREE 4 HD p. Smallville Season 9 Complete Download p p MKV RAR HD Mp4 Mobile Direct Download, Smallville S09 the cw tv series direct. The plot of the series Smallville tells about the young years of the Superman. In a small quiet town of Smallville falls meteor rain, after which the. Download Smallville Season 9 Episode 1. Hits: 0 | Size MB||Share This On: >> 1. GoStats hits counter. Today Hits Total hits: Watch Smallville - Season 9 in HD quality online for free, putlocker Smallville - Season 9. Free watching Smallville - Season 9, download Smallville - Season 9. Watch Smallville Season 9 () in HD quality online for free, putlocker Smallville Season 9 (), xmovies8 Smallville Season 9 (), download Smallville. Blu-ray, Digital Download or DVD Smallville Season 9 raining destruction on the unsuspecting citizens of Smallville, years pass, and the healing process. Smallville - Season 9, Smallville - Season 9 FULL free movies Online HD. You are watching the movie Smallville - Season 9 produced in download Smallville - Season 9 - , watch Smallville - Season 9. Watch Smallville - Season 9, Smallville - Season 9 Full free movies Online HD. A young Clark Kent struggles to find his place in the world. TVGuide has every full episode so you can stay-up-to-date and watch your favorite show Smallville anytime, anywhere. Smallville season 9 Completed - Free Movies Download. Season 9 guide for Smallville TV series - see the episodes list with schedule and episode summary. Track Smallville season 9 episodes. Preview and download your favorite episodes of Smallville, Season 9, or the entire season. -

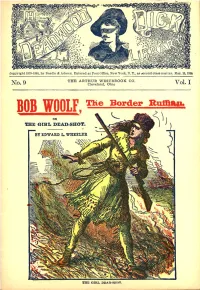

BOB WOOLF, Nle Border Rufbap

Copyr ight 1878-1884, by Beadle & Adams. En tered at Post omce, New York. N. Y .. as oecond class matter. Mar. 15, 18911. THE ARTHUR WESTBROOK CO. No.9 Cleveland, Ohio Vol. I BOB WOOLF, nle Border RufBap. OJ\ 'l!llE GIRL DEAD-SHOT. BY EDWARD L. WHEELER ~ -:s:~\'l THE GIRL DEAD-SHOT. \ I .:> pyrigh t 1878-1884, by Beadle '& Ada m s. E ntered at Post Omce, New York, N. Y. 1 as !:.econ d c lass m a t ter. 1\fa r. 15, 1£ryl TH:C ARTHUR WESTBROOK CO. · ~Tb.9 Clcv cl3:-id, Ohio Vol. I BOB WOOLF The Border Ruffian. ..... - ;;: -·' 01>• • ~·BE G IRL DEAD-S HOT. THE GIRL lJEAD·SHO'l', Rob Woolf, the Border Ruftlan. he has just r:illen But you cannot come in heN nor see him either." Bob Woolf. "Blast :vou, I'll see if I won't, ye little she-tiger!" cried tht" ruffi.an. " Dismount, bo:yees, an' stave in thet 'ar door l D'ye hear? stare it ml" THE BORDER RUFFl,A.N; "Hold I Bob Woolf?" cried the girl, her' eyes tla,•h• lng fire, '' hold! Come in here if you will; b n~ OR, first. lilt me tell you 10 so doing you w'll ~ yourself and men to the king of all scourges- "'l.ll· TB E GI&L DEAD-SHOT ~ 1JO,r ."', Had a C11.nnon-ball struck the border cbier be BY EDWARD L. WHEELER, could nnr. have been more startled. A.UTHOR OF "DEADWOOD DICK, ' ' "THE DOUBLE DAO· Jn an instant his companions were spurring away 11 0vPr the plain at a safe dista nce. -

Green Arrow: Archer's Quest (Green Arrow Quiver Book 3) Green Arrow: Archer's Quest (Green Arrow Quiver Book 3)

[Download free pdf] Green Arrow: Archer's Quest (Green Arrow Quiver Book 3) Green Arrow: Archer's Quest (Green Arrow Quiver Book 3) s5xMqgrfT Green Arrow: Archer's Quest (Green Arrow Quiver OzGmzreuj Book 3) O7Yiy2DnC JD-10483 XeC1uTTHC USmix/Data/US-2013 wiLMxC6qU 4/5 From 592 Reviews HbMy5txPx BRAD MELTZER nlw5uylFS ebooks | Download PDF | *ePub | DOC | audiobook cX7GDDFG8 w7NM64sg4 A5rIVQQOv 2U5S872Ch sVPEOmSGO HrCHZBGHQ 1MQLoVNJH 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Easily one of the best Green 6Hno6jynY Arrow books ever written.By HolyJIEbusGraphic Novel Review (9/10) 3xvhRJEcl AmazingGreen Arrow: The Archers Quest (Collecting GREEN ARROW #16-21; r8F5uE3b0 2001)Writer: Brad MeltzerArtist: Phil HesterSynopsis (from DC Comics): The GqeIH1UwN Emerald Archer returns from the dead and sets off on an adventure that tests his TqhVblfRn courage and brings formerly hidden facets of the Green Arrow legend to light. sYXoBw0V1 Featuring an introduction by Senator Patrick Leahy, a foreword by Greg Rucka qfkoXcIZB (WONDER WOMAN), Meltzer's original notes to the series, and the script to 6glSH0qX4 issue #16.Analysis: I fell in love with Meltzers writing after I read the Identity ByPPIRl7J Crisis (2004), which was a story with not much action, but with a hell of a lot of wEm5NOxjn stakes. Identity Crisis is also probably up there for me as one of my top ten best Zxs77Xt14 graphic novels of all time as it in essence it Watchmen-ised the Justice League SEAJVyTy7 and asked the question what would happen if the Justice League dealt with more SBXySKgSh emotional and realistic problems. -

PDF Download Green Arrow Pdf Free Download

GREEN ARROW PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Andrea Sorrentino,Jeff Lemire | 464 pages | 12 Jan 2016 | DC Comics | 9781401257613 | English | United States Green Arrow PDF Book Public Enemy 42m. So, I re-read it this year The Arrow has become a hero to the citizens of Starling City. Jayson, Jay January 8, While Oliver sets a trap to catch a group of crooked cops, Laurel takes Quentin to see Sara, who is feral and chained up in Laurel's basement. Ruin -- In Stores Now. Namespaces Article Talk. Jock's art is so gorgeous - not because of some photorealistic devotion to copying the real world see Deodato and Land , but instead because he captures in one sparse panel the feeling of pain of getting an arrow through the shoulder, of leaping for your life, of terror or dread or calm. His outlook on the world, how things should be, and his defense of the poor and working class made him a very unique character in the world of capes and tights. You must be a registered user to use the IMDb rating plugin. Meanwhile, Dinah's thirst for vengeance drives her to go rogue. Rating details. Disbanded 42m. Kondolojy, Amanda February 13, Related Characters: Black Canary. Later, Damien performs a blood ritual. Diggle and Lyla face issues in their marriage. Green Arrow: The Longbow Hunters. Also, the city needs an influx of people, which perhaps a new high speed rail line from Central City will provide. Retrieved October 9, The ongoing series Countdown showcased several of these. Later, Steve Aoki headlines the nightclub opening. -

The Red Badge of Courage / Stephen Crane

AG RED BADGE FM 8/9/06 8:46 AM Page i The Red Badge of Courage Stephen Crane THE EMC MASTERPIECE SERIES Access Editions SERIES EDITOR Laurie Skiba EMC/Paradigm Publishing St. Paul, Minnesota AG RED BADGE FM 8/9/06 8:46 AM Page ii Staff Credits: for EMC/Paradigm Publishing, St. Paul, Minnesota Laurie Skiba Paul Spencer Editor Art and Photo Researcher Lori Coleman Chris Nelson Associate Editor Editorial Assistant Brenda Owens Kristin Melendez Associate Editor Copy Editor Jennifer Anderson Sara Hyry Assistant Editor Contributing Writer Gia Garbinsky Christina Kolb Assistant Editor Contributing Writer for SYP Design & Production, Wenham, Massachusetts Sara Day Charles Bent Partner Partner All photos courtesy of Library of Congress. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Crane, Stephen, 1871–1900. The red badge of courage / Stephen Crane. p. cm. -- (The EMC masterpiece series access editions) Summary: During his service in the Civil War a young Union soldier matures to manhood and finds peace of mind as he comes to grips with his conflicting emotions about war. ISBN 0-8219-1981-4 1. Chancellorsville (Va.), Battle of, 1863 Juvenile fiction. [1. Chancellorsville (Va.), Battle of, 1863 Fiction. 2. United States--History-- Civil War, 1861–1865 Fiction.] I. Title. II. Series. PZ7.C852Re 199b [Fic]--dc21 99-36549 CIP ISBN 0-8219-1981-4 Copyright © 2000 by EMC Corporation All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be adapted, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, elec- tronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without permis- sion from the publisher. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 104 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 104 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 141 WASHINGTON, FRIDAY, JANUARY 13, 1995 No. 8 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. MESSAGE FROM THE SENATE The message also announced that the f A message from the Senate by Mr. Chair announces the following two ap- Hallen, one of its clerks, announced pointments made by the Democratic PRAYER that the Senate had passed with an leader, Mr. Mitchell, during the sine die adjournment: The Chaplain, Rev. James David amendment in which the concurrence Pursuant to Public Law 103±236, the Ford, D.D., offered the following pray- of the House is requested, a bill of the er: House of the following title: appointment of Mr. MOYNIHAN and Samuel P. Huntington of New York, as During these days when our memo- H.R. 1. An act to make certain laws appli- members of the Commission on Pro- ries are filled with the life and work of cable to the legislative branch of the Federal Martin Luther King, Jr., we recall, O Government. tecting and Reducing Government Se- crecy. God, the works of justice that he did The message also announced that the Pursuant to section 114(b)(1) of Pub- and inspired others to do and we re- Senate had passed a bill of the follow- lic Law 100±458, the reappointment of dedicate ourselves to what we should ing title, in which the concurrence of be and to the good works that we can William Winter to a 6-year term on the the House is requested: Board of Trustees of the John C.