Dabigatran Amoxicillin Clavulanate IV Treatment in the Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pharmacology of Amiodarone and Digoxin As Antiarrhythmic Agents

Part I Anaesthesia Refresher Course – 2017 University of Cape Town The Pharmacology of Amiodarone and Digoxin as Antiarrhythmic Agents Dr Adri Vorster UCT Department of Anaesthesia & Perioperative Medicine The heart contains pacemaker, conduction and contractile tissue. Cardiac arrhythmias are caused by either enhancement or depression of cardiac action potential generation by pacemaker cells, or by abnormal conduction of the action potential. The pharmacological treatment of arrhythmias aims to achieve restoration of a normal rhythm and rate. The resting membrane potential of myocytes is around -90 mV, with the inside of the membrane more negative than the outside. The main extracellular ions are Na+ and Cl−, with K+ the main intracellular ion. The cardiac action potential involves a change in voltage across the cell membrane of myocytes, caused by movement of charged ions across the membrane. This voltage change is triggered by pacemaker cells. The action potential is divided into 5 phases (figure 1). Phase 0: Rapid depolarisation Duration < 2ms Threshold potential must be reached (-70 mV) for propagation to occur Rapid positive charge achieved as a result of increased Na+ conductance through voltage-gated Na+ channels in the cell membrane Phase 1: Partial repolarisation Closure of Na+ channels K+ channels open and close, resulting in brief outflow of K+ and a more negative membrane potential Phase 2: Plateau Duration up to 150 ms Absolute refractory period – prevents further depolarisation and myocardial tetany Result of Ca++ influx -

Flucloxacillin Capsules in This Leaflet: 1 What Flucloxacillin Capsules Are

Flucloxacillin capsules This information is a summary only. It does not contain all information about this medicine. If you would like more information about the medicine you are taking, check with your doctor or other health care provider. No rights can be derived from the information provided in this medicine leaflet. In this leaflet: If you take more than you should 1 What Flucloxacillin capsules are and what they are used for If you (or someone else) swallow a lot of capsules at the same time, or you think a 2 Before you take child may have swallowed any contact your nearest hospital casualty department 3 How to take or tell your doctor immediately. Symptoms of an overdose include feeling or 4 Possible side effects being sick and diarrhoea. 5 How to store If you forget to take the capsules 1 What Flucloxacillin capsules are and what they are used for Do not take a double dose to make up for a forgotten dose. If you forget to take a Flucloxacillin is an antibiotic used to treat infections by killing the bacteria that dose take it as soon as you remember it and carry on as before, try to wait about can cause them. It belongs to a group of antibiotics called “penicillins”. four hours before taking the next dose. Flucloxacillin capsules are used to treat: • chest infections If you stop taking the capsules • throat or nose infections Do not stop treatment early because some bacteria may survive and cause the • ear infections infection to come back. • skin and soft tissue infections • heart infections 4 Possible side effects • bones and joints infections Like all medicines, Flucloxacillin capsules can cause side effects, although not • meningitis everybody gets them. -

Clinical Management of Staphylococcus Aureus Bacteremia in Neonates, Children, and Adolescents

Clinical Management of Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia in Neonates, Children, and Adolescents Brendan J. McMullan, BMed (Hons), FRACP, FRCPA,a,b,c,* Anita J. Campbell, MBBS, DCH, DipPID, FRACP,d,e,f,* Christopher C. Blyth, MBBS (Hons), PhD, DCH, FRACP, FRCPA,d,e,f,g J. Chase McNeil, BS, MD,h Christopher P. Montgomery, BA, MD,i,j Steven Y.C. Tong, MBBS (Hons), PhD, FRACP,k,l Asha C. Bowen, BA, MBBS, PhD, FRACPd,e,f,k,m Staphylococcus aureus is a common cause of community and health abstract – care associated bacteremia, with authors of recent studies estimating the aDepartment of Immunology and Infectious Diseases, incidence of S aureus bacteremia (SAB) in high-income countries between 8 Sydney Children’s Hospital, Randwick, New South Wales, , Australia; bSchool of Women’s and Children’s Health, and 26 per 100 000 children per year. Despite this, 300 children worldwide University of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales, have ever been randomly assigned into clinical trials to assess the efficacy Australia; cNational Centre for Infections in Cancer, of treatment of SAB. A panel of infectious diseases physicians with clinical University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; dDepartment of Infectious Diseases, Perth Children’s and research interests in pediatric SAB identified 7 key clinical questions. Hospital, Nedlands, Western Australia, Australia; The available literature is systematically appraised, summarizing SAB eWesfarmers Centre of Vaccines and Infectious Diseases, Telethon Kids Institute, Nedlands, Western Australia, -

Full Prescribing Information Warning: Suicidal Thoughts

tablets (SR) BUPROPION hydrochloride extended-release HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION anxiety, and panic, as well as suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, and completed suicide. Observe hydrochloride extended-release tablets (SR) was reported. However, the symptoms persisted in some Table 3. Adverse Reactions Reported by at Least 1% of Subjects on Active Treatment and at a tablets (SR) may be necessary when coadministered with ritonavir, lopinavir, or efavirenz [see Clinical These highlights do not include all the information needed to use bupropion hydrochloride patients attempting to quit smoking with Bupropion hydrochloride extended-release tablets, USP cases; therefore, ongoing monitoring and supportive care should be provided until symptoms resolve. Greater Frequency than Placebo in the Comparator Trial Pharmacology (12.3)] but should not exceed the maximum recommended dose. extended-release tablets (SR) safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for (SR) for the occurrence of such symptoms and instruct them to discontinue Bupropion hydrochloride Carbamazepine, Phenobarbital, Phenytoin: While not systematically studied, these drugs extended-release tablets, USP (SR) and contact a healthcare provider if they experience such adverse The neuropsychiatric safety of Bupropion hydrochloride extended-release tablets (SR) was evaluated in Bupropion Bupropion may induce the metabolism of bupropion and may decrease bupropion exposure [see Clinical bupropion hydrochloride extended-release tablets (SR). Nicotine events. (5.2) a randomized, double-blind, active-and placebo-controlled study that included patients without a history Hydrochloride Hydrochloride Pharmacology (12.3)]. If bupropion is used concomitantly with a CYP inducer, it may be necessary Transdermal BUPROPION hydrochloride extended-release tablets (SR), for oral use • Seizure risk: The risk is dose-related. -

Spectrum of Digoxin-Induced Ocular Toxicity: a Case Report and Literature Review Delphine Renard1*, Eve Rubli2, Nathalie Voide3, François‑Xavier Borruat3 and Laura E

Renard et al. BMC Res Notes (2015) 8:368 DOI 10.1186/s13104-015-1367-6 CASE REPORT Open Access Spectrum of digoxin-induced ocular toxicity: a case report and literature review Delphine Renard1*, Eve Rubli2, Nathalie Voide3, François‑Xavier Borruat3 and Laura E. Rothuizen1 Abstract Background: Digoxin intoxication results in predominantly digestive, cardiac and neurological symptoms. This case is outstanding in that the intoxication occurred in a nonagenarian and induced severe, extensively documented visual symptoms as well as dysphagia and proprioceptive illusions. Moreover, it went undiagnosed for a whole month despite close medical follow-up, illustrating the difficulty in recognizing drug-induced effects in a polymorbid patient. Case presentation: Digoxin 0.25 mg qd for atrial fibrillation was prescribed to a 91-year-old woman with an esti‑ mated creatinine clearance of 18 ml/min. Over the following 2–3 weeks she developed nausea, vomiting and dyspha‑ gia, snowy and blurry vision, photopsia, dyschromatopsia, aggravated pre-existing formed visual hallucinations and proprioceptive illusions. She saw her family doctor twice and visited the eye clinic once until, 1 month after starting digoxin, she was admitted to the emergency room. Intoxication was confirmed by a serum digoxin level of 5.7 ng/ml (reference range 0.8–2 ng/ml). After stopping digoxin, general symptoms resolved in a few days, but visual complaints persisted. Examination by the ophthalmologist revealed decreased visual acuity in both eyes, 4/10 in the right eye (OD) and 5/10 in the left eye (OS), decreased color vision as demonstrated by a score of 1/13 in both eyes (OU) on Ishihara pseudoisochromatic plates, OS cataract, and dry age-related macular degeneration (ARMD). -

Australian Public Assessment Refport for Ceftaroline Fosamil (Zinforo)

Australian Public Assessment Report for ceftaroline fosamil Proprietary Product Name: Zinforo Sponsor: AstraZeneca Pty Ltd May 2013 Therapeutic Goods Administration About the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) • The Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) is part of the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, and is responsible for regulating medicines and medical devices. • The TGA administers the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 (the Act), applying a risk management approach designed to ensure therapeutic goods supplied in Australia meet acceptable standards of quality, safety and efficacy (performance), when necessary. • The work of the TGA is based on applying scientific and clinical expertise to decision- making, to ensure that the benefits to consumers outweigh any risks associated with the use of medicines and medical devices. • The TGA relies on the public, healthcare professionals and industry to report problems with medicines or medical devices. TGA investigates reports received by it to determine any necessary regulatory action. • To report a problem with a medicine or medical device, please see the information on the TGA website <http://www.tga.gov.au>. About AusPARs • An Australian Public Assessment Record (AusPAR) provides information about the evaluation of a prescription medicine and the considerations that led the TGA to approve or not approve a prescription medicine submission. • AusPARs are prepared and published by the TGA. • An AusPAR is prepared for submissions that relate to new chemical entities, generic medicines, major variations, and extensions of indications. • An AusPAR is a static document, in that it will provide information that relates to a submission at a particular point in time. • A new AusPAR will be developed to reflect changes to indications and/or major variations to a prescription medicine subject to evaluation by the TGA. -

Flucloxacillin 500Mg Capsules BP (Flucloxacillin Sodium)

PACKAGE LEAFLET: INFORMATION FOR THE USER Flucloxacillin 250mg Capsules BP Flucloxacillin 500mg Capsules BP (flucloxacillin sodium) Read all of this leaflet carefully before you start taking Warnings and precautions this medicine because it contains important information Talk to your doctor or pharmacist before taking this medicine if for you. you: - Keep this leaflet. You may need to read it again. • are 50 years of age or older - If you have any further questions, ask your doctor, • have other serious illness (apart from the infection this pharmacist or nurse. medicine is treating). - This medicine has been prescribed for you only. Do not • suffer from kidney problems, as you may require a lower pass it on to others. It may harm them, even if their signs dose than normal (convulsions may occur very rarely in of illness are the same as yours. patients with kidney problems who take high doses). - If you get any side effects, talk to your doctor or • suffer from liver problems, as this medicine could cause pharmacist. This includes any possible side effects not them to worsen. listed in this leaflet. See section 4. • are taking this medicine for a long time as regular tests of liver and kidney function are advised What is in this leaflet • are taking or will be taking paracetamol 1. What Flucloxacillin Capsules are and what they are used • are on a sodium-restricted diet. for • are giving this medicine to a newborn child 2. What you need to know before you take Flucolxacillin Capsules The use of flucloxacillin, especially in high doses, may reduce 3. -

Guideline for Preoperative Medication Management

Guideline: Preoperative Medication Management Guideline for Preoperative Medication Management Purpose of Guideline: To provide guidance to physicians, advanced practice providers (APPs), pharmacists, and nurses regarding medication management in the preoperative setting. Background: Appropriate perioperative medication management is essential to ensure positive surgical outcomes and prevent medication misadventures.1 Results from a prospective analysis of 1,025 patients admitted to a general surgical unit concluded that patients on at least one medication for a chronic disease are 2.7 times more likely to experience surgical complications compared with those not taking any medications. As the aging population requires more medication use and the availability of various nonprescription medications continues to increase, so does the risk of polypharmacy and the need for perioperative medication guidance.2 There are no well-designed trials to support evidence-based recommendations for perioperative medication management; however, general principles and best practice approaches are available. General considerations for perioperative medication management include a thorough medication history, understanding of the medication pharmacokinetics and potential for withdrawal symptoms, understanding the risks associated with the surgical procedure and the risks of medication discontinuation based on the intended indication. Clinical judgement must be exercised, especially if medication pharmacokinetics are not predictable or there are significant risks associated with inappropriate medication withdrawal (eg, tolerance) or continuation (eg, postsurgical infection).2 Clinical Assessment: Prior to instructing the patient on preoperative medication management, completion of a thorough medication history is recommended – including all information on prescription medications, over-the-counter medications, “as needed” medications, vitamins, supplements, and herbal medications. Allergies should also be verified and documented. -

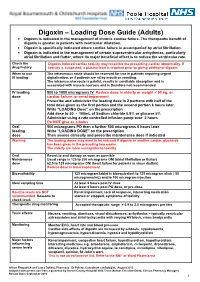

Digoxin – Loading Dose Guide (Adults) Digoxin Is Indicated in the Management of Chronic Cardiac Failure

Digoxin – Loading Dose Guide (Adults) Digoxin is indicated in the management of chronic cardiac failure. The therapeutic benefit of digoxin is greater in patients with ventricular dilatation. Digoxin is specifically indicated where cardiac failure is accompanied by atrial fibrillation. Digoxin is indicated in the management of certain supraventricular arrhythmias, particularly atrial fibrillation and flutter, where its major beneficial effect is to reduce the ventricular rate. Check the Digoxin-induced cardiac toxicity may resemble the presenting cardiac abnormality. If drug history toxicity is suspected, a plasma level is required prior to giving additional digoxin. When to use The intravenous route should be reserved for use in patients requiring urgent IV loading digitalisation, or if patients are nil by mouth or vomiting. The intramuscular route is painful, results in unreliable absorption and is associated with muscle necrosis and is therefore not recommended. IV loading 500 to 1000 micrograms IV Reduce dose in elderly or weight < 50 kg, or dose cardiac failure, or renal impairment Prescribe and administer the loading dose in 2 portions with half of the total dose given as the first portion and the second portion 6 hours later. Write “LOADING Dose” on the prescription Add dose to 50 - 100mL of Sodium chloride 0.9% or glucose 5% Administer using a rate controlled infusion pump over 2 hours Do NOT give as a bolus Oral 500 micrograms PO then a further 500 micrograms 6 hours later loading Write “LOADING DOSE” on the prescription dose Then assess clinically and prescribe maintenance dose if indicated Warning The loading doses may need to be reduced if digoxin or another cardiac glycoside has been given in the preceding two weeks. -

PRODUCT MONOGRAPH Pr WELLBUTRIN XL Bupropion

PRODUCT MONOGRAPH Pr WELLBUTRIN XL Bupropion Hydrochloride Extended-Release Tablets, USP 150 mg and 300 mg Antidepressant Name: Date of Revision: Valeant Canada LP March 20, 2017 Address: 2150 St-Elzear Blvd. West Laval, QC, H7L 4A8 Control Number: 200959 Table of Contents Page PART I: HEALTH PROFESSIONAL INFORMATION .............................................................. 2 SUMMARY PRODUCT INFORMATION ................................................................................. 2 INDICATIONS AND CLINICAL USE ....................................................................................... 2 CONTRAINDICATIONS ............................................................................................................ 3 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS ........................................................................................... 3 ADVERSE REACTIONS ............................................................................................................. 9 DRUG INTERACTIONS ........................................................................................................... 19 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION ....................................................................................... 22 OVERDOSAGE ......................................................................................................................... 24 ACTION AND CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY ..................................................................... 25 STORAGE AND STABILITY .................................................................................................. -

Impetigo: Antimicrobial Prescribing

DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION 1 Impetigo: antimicrobial prescribing 2 NICE guideline 3 Draft for consultation, August 2019 This guideline sets out an antimicrobial prescribing strategy for impetigo. It aims to optimise antibiotic use and reduce antibiotic resistance. The recommendations in this guideline are for the use of antiseptics and antibiotics to manage impetigo in adults, young people and children. It does not cover diagnosis. Please note that the scope of this guideline is for adults, young people and children aged 72 hours and over. For treatment of children in the first 72 hours of life, please seek specialist advice. For managing other skin infections, see our web page on skin conditions. See a 2-page visual summary of the recommendations, including tables to support prescribing decisions. Who is it for? • Healthcare professionals • Adults, young people and children with impetigo, their parents and carers The guideline contains: • the draft recommendations • the rationales • summary of the evidence. Information about how the guideline was developed is on the guideline’s page on the NICE website. This includes the full evidence review, details of the committee and any declarations of interest. Impetigo: antimicrobial prescribing guidance DRAFT (August 2019) Page 1 of 20 DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION 1 Recommendations 2 1.1 Managing impetigo 3 Advice to reduce the spread of impetigo 4 1.1.1 Advise adults, young people and children, and their parents or 5 carers if appropriate, about good hygiene measures to reduce the 6 spread of impetigo to other areas of the body and to other people. To find out why the committee made the recommendations on advice to reduce the spread of impetigo see the rationales. -

Treatment for Calcium Channel Blocker Poisoning: a Systematic Review

Clinical Toxicology (2014), 52, 926–944 Copyright © 2014 Informa Healthcare USA, Inc. ISSN: 1556-3650 print / 1556-9519 online DOI: 10.3109/15563650.2014.965827 REVIEW ARTICLE Treatment for calcium channel blocker poisoning: A systematic review M. ST-ONGE , 1,2,3 P.-A. DUB É , 4,5,6 S. GOSSELIN ,7,8,9 C. GUIMONT , 10 J. GODWIN , 1,3 P. M. ARCHAMBAULT , 11,12,13,14 J.-M. CHAUNY , 15,16 A. J. FRENETTE , 15,17 M. DARVEAU , 18 N. LE SAGE , 10,14 J. POITRAS , 11,12 J. PROVENCHER , 19 D. N. JUURLINK , 1,20,21 and R. BLAIS 7 1 Ontario and Manitoba Poison Centre, Toronto, ON, Canada 2 Institute of Medical Science, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada 3 Department of Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada 4 Direction of Environmental Health and Toxicology, Institut national de sant é publique du Qu é bec, Qu é bec, QC, Canada 5 Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Qu é bec, Qu é bec, QC, Canada 6 Faculty of Pharmacy, Université Laval, Qu é bec, QC, Canada 7 Centre antipoison du Qu é bec, Qu é bec, QC, Canada 8 Department of Medicine, McGill University, Montr é al, QC, Canada 9 Toxicology Consulting Service, McGill University Health Centre, Montr é al, QC, Canada 10 Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Qu é bec, Qu é bec, QC, Canada 11 Centre de sant é et services sociaux Alphonse-Desjardins (CHAU de Lévis), L é vis, QC, Canada 12 Department of Family Medicine and Emergency Medicine, Universit é Laval, Québec, QC, Canada 13 Division de soins intensifs, Universit é Laval, Qu é bec, QC, Canada 14 Populations