Health and Social Care Overview and Scrutiny Committee Review of In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Council, 08/12/2020 14:00

Public Document Pack Agenda Council Time and Date 2.00 pm on Tuesday, 8th December, 2020 Place This meeting will be held remotely. The meeting can be viewed live by pasting this link into your browser: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_gSCLeLs5lc&feature=youtu.be 1. Apologies 2. Minutes of the Meeting held on 20 October 2020 (Pages 5 - 12) 3. Exclusion of the Press and Public To consider whether to exclude the press and public for the item of private business for the reasons shown in the report. 4. Correspondence and Announcements of the Lord Mayor 5. Petitions 6. Declarations of Interest Matters Left for Determination by the City Council/Recommendations for the City Council It is anticipated that the following matters will be referred as Recommendations. The reports are attached. The relevant Recommendations will be circulated separately 7. Audit and Procurement Committee Annual Report 2019-20 (Pages 13 - 18) From the Audit and Procurement Committee, 30 November 2020 8. Public Sector Decarbonisation Scheme - CCC Public Building Energy Efficiency Retrofit (Pages 19 - 30) From the Cabinet, 1 December 2020 9. Review of Local Plan (Pages 31 - 40) From the Cabinet, 1 December 2020 Page 1 10. Surrender of Lease on Premises in Upper Precinct, Coventry (Pages 41 - 50) From the Cabinet, 1 December 2020 Items for Consideration 11. Recommendation of Ethics Committee Following Code of Conduct Hearing (Pages 51 - 60) Report of the Director of Law and Governance 12. Review of Members' Allowances Scheme (Pages 61 - 74) Report of the Director of Law and Governance 13. Adoption of Definitions of Anti-Semitism and Islamophobia (Pages 75 - 84) Report of the Director of Law and Governance 14. -

Keynote Speaker

SHOES Conference – Bios Key Note Speakers David Stuckler David Stuckler, PhD, MPH, HonMFPH, FRSA is a Professor of Political Economy and Sociology at University of Oxford and research fellow of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. He has written over 170 peer-reviewed scientific articles on global health in The Lancet, British Medical Journal and Nature in addition to other major journals. His book about the global chronic-disease epidemic, Sick Societies, was published by Oxford University Press in 2011. He is also an author of The Body Economic, published by Penguin Press in 2013 and translated into over ten languages. His work has featured on covers of the New York Times and The Economist, among other venues. Foreign Policy named him one of the top 100 global thinkers of 2013 Dr Stephen Watkins Born and bred in Lancashire, England, Steve, a rambler and railway enthusiast, qualified in medicine in 1974, obtained his public health master’s degree in 1982 and has been a Director of Public Health for Stockport since 1990. He was one of the founder members of the Transport & Health Study Group when it was launched in 1989 and became its chair a few years later. In 2013 when the role of chair was split in two he became the Co-chair (Policy). He was a co-author and editor of Health on the Move and of Health on the Move 2. His interests in public health include not only transport but also the health effects of economic policy. He is a Council member of the British Medical Association and a former President of the Medical Practitioners Union (a UK body which describes itself as the medical organisation of the social movements of the people). -

“If You Could Do One Thing…” Local Actions to Promote Social Integration

“If you could do one thing…” Local actions to promote social integration Interim Report: Findings from the Call for Evidence, August 2017 By Dr Madeleine Mosse “If you could do one thing…” Local actions to promote social integration • • • “If you could do one thing…” Local actions Summary • • • to promote social 45 responses to the Call for Evidence received, integration alongside findings from five key informant Interim Report: Findings from the Call for Evidence, interviews. August 2017 Six “Key Themes” identified: Overview of evidence collected 1. Language Learning 2. Understanding how 45 responses to the Call for Evidence were received: Systems and Processes Work • 14 from Local Authorities: Bedford Borough Council; 3. Children & Young Walsall Metropolitan Borough Council; London City People Council; Leeds City Council; Carmarthenshire County 4. Building Trust in Council; Cambridge City Council; City of Bradford Local Communities Metropolitan District Council; Plymouth City Council; and Overcoming London Borough of Bexley; Sutton London Borough Grievances Council; Swansea City Council, Manchester City Council, 5. Women & Girls Coventry City Council, London Borough of Tower Hamlets 6. Employment & Training • 22 from Third Sector organisations, of which 3 were national, 18 were local or regional, and 1 was a national funding body From these findings criteria for Case Studies • 10 from academics has been proposed. 1 Introduction: The British Academy is examining successful integration projects from around the UK; drawing lessons from clear evidence about methods which are proven to improve integration and result in long term cohesion in our society. We believe this work is well timed, coming as it does at a stage when the global population is shifting and Europe is witnessing changing migration patterns. -

Mifriendly Cities – Migration Friendly Cities Birmingham, Coventry and Wolverhampton 2017/18-2020/21

MiFriendly Cities – Migration Friendly Cities Birmingham, Coventry and Wolverhampton 2017/18-2020/21 Summary In partnership with Coventry City and Wolverhampton City Councils, Birmingham City Council has been successful in securing EU funding to deliver a three year MiFriendly Cities project. The project, which is backed by West Midlands Combined Authority, will see the three Councils working together to develop new and innovative activity which can help integrate economic migrants, refugees and asylum seekers into the West Midlands. This approach provides an opportunity for Birmingham City Council to explore how it can work with partners and migrants in a way which can help to expand the current range of activity, which mostly focuses on addressing the basic needs and legal rights of migrants. As part of this approach there is a particular focus on changing attitudes to migrants, developing employment pathways, social enterprise and active citizenship. Coventry City Council will be managing the whole project but Birmingham City Council will be required to project manage and coordinate activity which specifically relates to Birmingham, across all the different work packages and activities. Birmingham has also been asked to lead the regional work on “Active Citizenship”. Introduction Following a competitive bidding process “MiFriendly Cities” was chosen by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) as one of three projects across Europe which they would like to support. This was from two hundred proposals which were submitted. To support the delivery of the MiFriendly Cities project the EU is providing €4,280,640 over three years to Birmingham, Coventry and Wolverhampton City Councils. This is irrespective of the Brexit process and the UK leaving the EU in 2019. -

Q2 1617 LA Referrals

Referrals to Local Authority Adoption Agencies from First4Adoption by region Q2 July-September 2016 Yorkshire & The Humber LA Adoption Agencies North East LA Adoption Agencies Durham County Council 13 North Yorkshire County Council* 30 1 Northumberland County Council 8 Barnsley Adoption Fostering Unit 11 South Tyneside Council 8 Rotherham Metropolitan Borough Council 11 2 North Tyneside Council 5 Bradford Metropolitan Borough Council 10 Redcar Cleveland Borough Council 5 Hull City Council 10 1 Web Referrals Phone Referrals Middlesbrough Council 3 East Riding Of Yorkshire Council 9 City Of Sunderland 2 Cumbria County Council 7 Gateshead Council 2 Calderdale Metropolitan Borough Council 6 1 Newcastle Upon Tyne City Council 2 0 3.5 7 10.5 14 Leeds City Council 6 1 Web Referrals Phone Referrals Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council 5 Hartlepool Borough Council 4 North Lincolnshire Adoption Service 4 1 City Of York Council 3 North East Lincolnshire Adoption Service 3 1 Darlington Borough Council 2 Kirklees Metropolitan Council 2 1 Sheffield Metropolitan City Council 2 Wakefield Metropolitan District Council 2 * Denotes agencies with more than one office entry on the agency finder 0 10 20 30 40 North West LA Adoption Agencies Liverpool City Council 30 Cheshire West And Chester County Council 16 Bolton Metropolitan Borough Council 11 1 Manchester City Council 9 WWISH 9 Lancashire County Council 8 Oldham Council 8 1 Sefton Metropolitan Borough Council 8 2 Web Referrals Phone Referrals Wirral Adoption Team 8 Salford City Council 7 3 Bury Metropolitan -

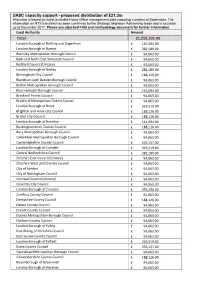

UASC Capacity Support - Proposed Distribution of £21.3M Allocation Is Based on Latest Available Home Office Management Data Capturing Numbers at September

UASC capacity support - proposed distribution of £21.3m Allocation is based on latest available Home Office management data capturing numbers at September. The information on NTS transfers has been confirmed by the Strategic Migration Partnership leads and is accurate up to December 2017. Please see attached FAQ and methodology document for further information. Local Authority Amount Total 21,258,203.00 London Borough of Barking and Dagenham £ 141,094.00 London Borough of Barnet £ 282,189.00 Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council £ 94,063.00 Bath and North East Somerset Council £ 94,063.00 Bedford Council (Unitary) £ 94,063.00 London Borough of Bexley £ 282,189.00 Birmingham City Council £ 188,126.00 Blackburn with Darwen Borough Council £ 94,063.00 Bolton Metropolitan Borough Council £ 94,063.00 Bournemouth Borough Council £ 141,094.00 Bracknell Forest Council £ 94,063.00 Bradford Metropolitan District Council £ 94,063.00 London Borough of Brent £ 329,219.00 Brighton and Hove City Council £ 188,126.00 Bristol City Council £ 188,126.00 London Borough of Bromley £ 141,094.00 Buckinghamshire County Council £ 188,126.00 Bury Metropolitan Borough Council £ 94,063.00 Calderdale Metropolitan Borough Council £ 94,063.00 Cambridgeshire County Council £ 235,157.00 London Borough of Camden £ 329,219.00 Central Bedfordshire Council £ 282,189.00 Cheshire East Council (Unitary) £ 94,063.00 Cheshire West and Chester Council £ 94,063.00 City of London £ 94,063.00 City of Nottingham Council £ 94,063.00 Cornwall Council (Unitary) £ 94,063.00 Coventry City -

Waste Strategy (2019)

Waste Strategy City of Newcastle upon Tyne 2019 Waste Strategy City of Newcastle upon Tyne 2019 Cabinet Member Foreword The world is producing more and more waste. Councillor There is also a renewed and widespread Nick Kemp, passion for environmental issues. We helped Cabinet to establish the independent Newcastle Member Waste Commission, the first of its kind in the for the country, to address the problem of increasing Environment waste. The ambition for our City is that we can become a model of excellence and through our refreshed Waste Strategy have We need to think about our impact on the the ambition to transform the way we think environment now and for the sake of future about waste and the flexibility to manage generations. waste operations as opportunities arise. We need to think differently about the Above all we want to inspire individuals things we throw away and make sure and organisations to take responsibility for that we have given them every chance to changing their behaviour relating to waste become useful again. At the same time, we and to be proud of their communities and the need to encourage and educate residents environment we live in. and businesses to reduce the amount of In December 2018 the government published rubbish they produce in the first place. its 25 year plan to improve the environment This may be through small acts such as and whilst this “Resources and Waste careful meal planning and shopping or for Strategy” is out for public consultation, we businesses something more radical such recognise the challenges this may bring. -

List of Councils in England by Type

List of councils in England by type There are a total of 343 councils in England: • Metropolitan districts (36) • London boroughs (32) plus the City of London • Unitary authorities (55) plus the Isles of Scilly • County councils (26) • District councils (192) Metropolitan districts (36) 1. Barnsley Borough Council 19. Rochdale Borough Council 2. Birmingham City Council 20. Rotherham Borough Council 3. Bolton Borough Council 21. South Tyneside Borough Council 4. Bradford City Council 22. Salford City Council 5. Bury Borough Council 23. Sandwell Borough Council 6. Calderdale Borough Council 24. Sefton Borough Council 7. Coventry City Council 25. Sheffield City Council 8. Doncaster Borough Council 26. Solihull Borough Council 9. Dudley Borough Council 27. St Helens Borough Council 10. Gateshead Borough Council 28. Stockport Borough Council 11. Kirklees Borough Council 29. Sunderland City Council 12. Knowsley Borough Council 30. Tameside Borough Council 13. Leeds City Council 31. Trafford Borough Council 14. Liverpool City Council 32. Wakefield City Council 15. Manchester City Council 33. Walsall Borough Council 16. North Tyneside Borough Council 34. Wigan Borough Council 17. Newcastle Upon Tyne City Council 35. Wirral Borough Council 18. Oldham Borough Council 36. Wolverhampton City Council London boroughs (32) 1. Barking and Dagenham 17. Hounslow 2. Barnet 18. Islington 3. Bexley 19. Kensington and Chelsea 4. Brent 20. Kingston upon Thames 5. Bromley 21. Lambeth 6. Camden 22. Lewisham 7. Croyd on 23. Merton 8. Ealing 24. Newham 9. Enfield 25. Redbridge 10. Greenwich 26. Richmond upon Thames 11. Hackney 27. Southwark 12. Hammersmith and Fulham 28. Sutton 13. Haringey 29. Tower Hamlets 14. -

Community Cohesion – an Action Guide

community cohesion – an action guide researchguidance into for localthe balance authorities of funding review community cohesion All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be This action guide has been produced reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any in partnership by the Local Government means, mechanical, photocopying, recording or Association, Audit Commission, otherwise, or stored in any retrieval system of any Commission for Racial Equality, Home nature, without the prior permission of the copyright Office, Improvement and Development holder. Agency, The Inter Faith Network and the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister. Copyright © Local Government Association 2004 Published by LGA Publications Local Government Association, Local Government House, Smith Square, London SW1P 3HZ Tel 020 7664 3131 Fax 020 7664 3030 LGA Code F/EQ009 ISBN 1 84049 444 1 community cohesion contents Foreword 4 1 Introduction 5 2 Defining community cohesion 7 3 Vision, values and strategy 8 4 Measuring community cohesion 12 5 Working with the local strategic partnership 16 6 Conflict resolution 21 7 Working with black and minority ethnic (BME) communities 25 8 Working with faith communities 29 9 Working with the voluntary and community sector 34 10 Working with the media 38 11 Embedding community cohesion in delivering services 41 12 Working with the police and the fire service 43 13 Housing 50 14 Regeneration 57 15 Arts, sport and other cultural services 61 16 Education 65 17 Children and young people 70 18 Older people and intergenerational cohesion 75 19 Asylum seekers and refugees 78 20 Gypsies and Travellers 83 21 Case studies on other aspects of community cohesion 87 community cohesion – an action guide 3 foreword Community cohesion lies at the heart of what makes a safe and strong community. -

Social Determinants of Health and the Role of Local Government

Social determinants of health and the role of local government Report Social determinants of health 1 Foreword The desire for good health can be seen all around us, whether in people taking more exercise or in trends on social media. The COVID-19 pandemic has added to concerns about health and wellbeing. It is common to receive emails that begin with the general greeting: “I hope you are well”. In local government it is important to consider what we can do to improve health within our communities, so that residents live longer happier and healthier lives. Health is often thought of as more of a concern for the NHS than for local government, but in reality, local government has an even greater potential to influence health improvement than does the NHS. As was quoted in the recent All Parliamentary Report on longevity: “We have been caught in a false view that our national health means the NHS.”1 Health improvement has always been a fundamental responsibility of local government and this was emphasised further with the transfer of public health responsibilities in 2013. It is now seven years since that transfer. It is 10 years since the landmark publication of the Marmot report, ‘Fair Society Healthy Lives’2 and it is also 10 years since the Local Government Association (LGA) last produced a report on the social determinants of health.3 The role of local government at that time was set out as the following: as an employer; through the services it commissions and delivers; through its regulatory powers; through community leadership; through its well-being power. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Investment Board, 20/07/2020 10:00

Public Document Pack Investment Board Date: Monday 20 July 2020 Time: 10.00 am Public meeting Yes Venue: This meeting is being held entirely by video conference facilities Please click here to view the meeting Membership Councillor Bob Sleigh (Chair) Portfolio Lead for Finance & Investments Nick Abell Coventry & Warwickshire Local Enterprise Partnership Councillor Wasim Ali Sandwell Metropolitan Borough Council Councillor Mike Bird Walsall Metropolitan Borough Council Paul Brown Black Country Local Enterprise Partnership Councillor Tristan Chatfield Birmingham City Council Councillor Steve Clark Dudley Metropolitan Borough Council Councillor Karen Grinsell Solihull Metropolitan Borough Council Councillor Tony Jefferson Non-Constituent Authorities Councillor Jim O'Boyle Coventry City Council Councillor Stephen Simkins City of Wolverhampton Council Sue Summers West Midlands Development Capital Gary Taylor Greater Birmingham & Solihull Local Enterprise Partnership Quorum for this meeting shall be four members. If you have any queries about this meeting, please contact: Contact Carl Craney Governance Services Officer West Midlands Combined Authority Telephone 0121 214 7965 Email [email protected] AGENDA No. Item Presenting Pages Meeting Business Items 1. Apologies for Absence (if any) Chair None 2. Declarations of Interests (if any) Carl Craney None 3. Minutes of last meeting Chair 1 - 10 Business Items for Noting 4. Investment Programme Update and Dashboard Linda Horne / Ian 11 - 28 Martin 5. SQW Update - Presentation Andy Morgan 29 - 32 6. Very Light Rail (VLR) - Presentation Colin Knight 33 - 50 7. WMCA Collective Investment Fund (CIF) - Nick Oakley 51 - 54 Dashboard 8. WMCA Brownfield Land and Property Nick Oakley 55 - 58 Development Fund (BLPDF) - Dashboard 9. WMCA Revolving Investment Fund (RIF) - Nick Oakley 59 - 62 Dashboard 10. -

CIL Draft Charging Schedule Duty to Co-Operate

CIL Draft Charging Schedule Duty to Co-operate The Draft Charging Schedule for CIL is out for consultation from Thursday 17th April until Thursday 29th April 2014 Local Planning Authorities and other bodies party to this agreement/ understanding: A. Sandwell MBC B. Dudley MBC Walsall MBC Wolverhampton City Council Birmingham City Council Coventry City Council Solihull MBC Wyre Forest District Council Bromsgrove District Council South Staffordshire District Council Worcestershire County Council Staffordshire County Council C. Environment Agency; English Heritage; Natural England; Civil Aviation Authority; Homes and Communities Agency; Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG); NHS Commissioning Board; Office of Rail Regulation; Centro; The Highway Authority Marine Management Organisation; Local Enterprise Partnership; Local Nature Partnership. Local Development Document(s) covered by this agreement / understanding: CIL Stage in the process forming part of this agreement: Draft Charging Schedule As detailed in paragraphs 178-181 of the National Planning Policy Framework, public bodies have a Duty to Co-operate on strategic planning issues that cross administrative boundaries. The Council therefore invites you to complete the table below and welcomes comments on which issues will need to be addressed. [IL0: UNCLASSIFIED] If you believe there are some cross boundary issues that need addressing, what measures do you feel are required to address these and what would you consider to be the estimated timescales? No comments at this stage. Name Michael Brereton Organisation Walsall Council Postal Address 2nd Floor Civic Centre, Darwall Street, Walsall, WS1 1DG. Email Address [IL0: UNCLASSIFIED] .