Cenozoic Mass Extinctions in the Deep Sea: What Perturbs the Largest Habitat on Earth?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 30. Latest Oligocene Through Early Miocene Isotopic Stratigraphy

Shackleton, N.J., Curry, W.B., Richter, C., and Bralower, T.J. (Eds.), 1997 Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results, Vol. 154 30. LATEST OLIGOCENE THROUGH EARLY MIOCENE ISOTOPIC STRATIGRAPHY AND DEEP-WATER PALEOCEANOGRAPHY OF THE WESTERN EQUATORIAL ATLANTIC: SITES 926 AND 9291 B.P. Flower,2 J.C. Zachos,2 and E. Martin3 ABSTRACT Stable isotopic (d18O and d13C) and strontium isotopic (87Sr/86Sr) data generated from Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) Sites 926 and 929 on Ceara Rise provide a detailed chemostratigraphy for the latest Oligocene through early Miocene of the western Equatorial Atlantic. Oxygen isotopic data based on the benthic foraminifer Cibicidoides mundulus exhibit four distinct d18O excursions of more than 0.5ä, including event Mi1 near the Oligocene/Miocene boundary from 23.9 to 22.9 Ma and increases at about 21.5, 18 and 16.5 Ma, probably reßecting episodes of early Miocene Antarctic glaciation events (Mi1a, Mi1b, and Mi2). Carbon isotopic data exhibit well-known d13C increases near the Oligocene/Miocene boundary (~23.8 to 22.6 Ma) and near the early/middle Miocene boundary (~17.5 to 16 Ma). Strontium isotopic data reveal an unconformity in the Hole 926A sequence at about 304 meters below sea ßoor (mbsf); no such unconformity is observed at Site 929. The age of the unconfor- mity is estimated as 17.9 to 16.3 Ma based on a magnetostratigraphic calibration of the 87Sr/86Sr seawater curve, and as 17.4 to 15.8 Ma based on a biostratigraphic calibration. Shipboard biostratigraphic data are more consistent with the biostratigraphic calibration. -

Reduced El Niño–Southern Oscillation During the Last Glacial

RESEARCH | REPORTS PALEOCEANOGRAPHY vergent results and our newly generated data by considering geographic location, choice of fora- minifera species, and changes in thermocline – depth (see supplementary materials). Reduced El Niño Southern Oscillation ENSO variability is asymmetric (the El Niño warm phase is more extreme than the La Niña during the Last Glacial Maximum cold phase) (14), so temperature variations in the equatorial Pacific are not normally distrib- Heather L. Ford,1,2* A. Christina Ravelo,1 Pratigya J. Polissar2 uted (7, 15), and statistical tests that assume normality (e.g., standard deviation) can lead to El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is a major source of global interannual variability, but erroneous conclusions with respect to changes its response to climate change is uncertain. Paleoclimate records from the Last Glacial in variance. Therefore, we use quantile-quantile Maximum (LGM) provide insight into ENSO behavior when global boundary conditions (Q-Q) plots—a simple, yet powerful way to vi- — (ice sheet extent, atmospheric partial pressure of CO2) were different from those today. sualize distribution data to compare the tem- In this work, we reconstruct LGM temperature variability at equatorial Pacific sites perature range and distribution recorded by two using measurements of individual planktonic foraminifera shells. A deep equatorial populations of individual foraminifera shells to thermocline altered the dynamics in the eastern equatorial cold tongue, resulting in interpret possible climate forcing mechanisms. reduced ENSO variability during the LGM compared to the Late Holocene. These results Sensitivity studies using modern hydrographic suggest that ENSO was not tied directly to the east-west temperature gradient, as data show how changes in ENSO and seasonality previously suggested. -

Exhibit Specimen List FLORIDA SUBMERGED the Cretaceous, Paleocene, and Eocene (145 to 34 Million Years Ago) PARADISE ISLAND

Exhibit Specimen List FLORIDA SUBMERGED The Cretaceous, Paleocene, and Eocene (145 to 34 million years ago) FLORIDA FORMATIONS Avon Park Formation, Dolostone from Eocene time; Citrus County, Florida; with echinoid sand dollar fossil (Periarchus lyelli); specimen from Florida Geological Survey Avon Park Formation, Limestone from Eocene time; Citrus County, Florida; with organic layers containing seagrass remains from formation in shallow marine environment; specimen from Florida Geological Survey Ocala Limestone (Upper), Limestone from Eocene time; Jackson County, Florida; with foraminifera; specimen from Florida Geological Survey Ocala Limestone (Lower), Limestone from Eocene time; Citrus County, Florida; specimens from Tanner Collection OTHER Anhydrite, Evaporite from early Cenozoic time; Unknown location, Florida; from subsurface core, showing evaporite sequence, older than Avon Park Formation; specimen from Florida Geological Survey FOSSILS Tethyan Gastropod Fossil, (Velates floridanus); In Ocala Limestone from Eocene time; Barge Canal spoil island, Levy County, Florida; specimen from Tanner Collection Echinoid Sea Biscuit Fossils, (Eupatagus antillarum); In Ocala Limestone from Eocene time; Barge Canal spoil island, Levy County, Florida; specimens from Tanner Collection Echinoid Sea Biscuit Fossils, (Eupatagus antillarum); In Ocala Limestone from Eocene time; Mouth of Withlacoochee River, Levy County, Florida; specimens from John Sacha Collection PARADISE ISLAND The Oligocene (34 to 23 million years ago) FLORIDA FORMATIONS Suwannee -

PALEOGENE FOSSILS and the RADIATION of MODERN BIRDS H�Q�� F

The Auk 122(4):1049–1054, 2005 © The American Ornithologists’ Union, 2005. Printed in USA. OVERVIEW PALEOGENE FOSSILS AND THE RADIATION OF MODERN BIRDS Hq F. Jrx1 Division of Birds, MRC-116, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. 20013, USA M birds arose mainly in 1989, Mayr and Manegold 2004), and others. the Neogene Period (1.8–23.8 mya), and mod- Paleogene fossils also document diverse extinct ern species mainly in the Plio-Pleistocene branches of the neornithine tree, ranging from (0.08–5.3 mya). Neogene fossil birds generally large pseudotoothed seabirds to giant fl ightless resemble modern taxa, and those that cannot land birds to small zygodactyl perching birds be a ributed to a modern genus or species (Ballmann 1969, Harrison and Walker 1976, can usually be placed in a modern family with Andors 1992). a fair degree of confi dence (e.g. Becker 1987, Before the Paleogene, fossils of putative neor- Olson and Rasmussen 2001). Fossil birds from nithine birds are sparse and fragmentary (Hope earlier in the Cenozoic can be more challeng- 2002), and their phylogenetic placement is all ing to classify. The fossil birds of the Paleogene the more equivocal. The Paleogene is thus a cru- (23.8–65.5 mya) are clearly a ributable to the cial time period for understanding the history of Neornithes (modern birds), and the earliest diversifi cation of birds, particularly with respect well-established records of most traditional to the deeper branches of the neornithine tree. orders and families of modern birds occur then. -

The Geologic Time Scale Is the Eon

Exploring Geologic Time Poster Illustrated Teacher's Guide #35-1145 Paper #35-1146 Laminated Background Geologic Time Scale Basics The history of the Earth covers a vast expanse of time, so scientists divide it into smaller sections that are associ- ated with particular events that have occurred in the past.The approximate time range of each time span is shown on the poster.The largest time span of the geologic time scale is the eon. It is an indefinitely long period of time that contains at least two eras. Geologic time is divided into two eons.The more ancient eon is called the Precambrian, and the more recent is the Phanerozoic. Each eon is subdivided into smaller spans called eras.The Precambrian eon is divided from most ancient into the Hadean era, Archean era, and Proterozoic era. See Figure 1. Precambrian Eon Proterozoic Era 2500 - 550 million years ago Archaean Era 3800 - 2500 million years ago Hadean Era 4600 - 3800 million years ago Figure 1. Eras of the Precambrian Eon Single-celled and simple multicelled organisms first developed during the Precambrian eon. There are many fos- sils from this time because the sea-dwelling creatures were trapped in sediments and preserved. The Phanerozoic eon is subdivided into three eras – the Paleozoic era, Mesozoic era, and Cenozoic era. An era is often divided into several smaller time spans called periods. For example, the Paleozoic era is divided into the Cambrian, Ordovician, Silurian, Devonian, Carboniferous,and Permian periods. Paleozoic Era Permian Period 300 - 250 million years ago Carboniferous Period 350 - 300 million years ago Devonian Period 400 - 350 million years ago Silurian Period 450 - 400 million years ago Ordovician Period 500 - 450 million years ago Cambrian Period 550 - 500 million years ago Figure 2. -

The Cenozoic Era - Nýlífsöld 65 MY-Present Jarðsaga 2 Ólafur Ingólfsson Origin of the Term: the Tertiary Tertiary System

The Cenozoic Era - Nýlífsöld 65 MY-Present Jarðsaga 2 Ólafur Ingólfsson Origin of the Term: The Tertiary Tertiary System. [1760] Named by Giovanni Arduino Period as the uppermost part of his 65-1.8 MY three-fold subdivision of mountains in northern Italy. The Tertiary became a formal period and system when Lyell published his work describing further subdivisions of the Tertiary. The Tertiary Period is divided into five epochs (tímar): Paleocene (65-56 MY), Eocene (56-34 MY), Oligocene (34-24 MY), Miocene (24-5,3 MY), and Pliocene (5,3-1,8 MY). Confusing set of stratigraphic terms... More than 95% of the Cenozoic era belongs to the Tertiary period. During the 18th century the names Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary were given by Giovanni Arduino to successive rock strata, the Primary being the oldest, the Tertiary the more recent. In 1829 a fourth division, the Quaternary, was added by P. G. Desnoyers. These terms were later abandoned, the Primary becoming the Paleozoic Era, and the Secondary the Mesozoic. But Tertiary and Quaternary were retained for the two main stages of the Cenozoic. Attempts to replace the "Tertiary" with a more reasonable division of “Palaeogene” (early Tertiary) and “Neogene” (later Tertiary and Quaternary) have not been very successful. Stanley uses this division. The World at the K/T Boundary Paleocene plate tectonics During the Paleocene, the inland seas of the Cretaceous Period dry up, exposing large land areas in North America and Eurasia. Australia begins to separate from Antarctica, and Greenland splits from North America. A remnant Tethys Sea persists in the equatorial region. -

3. Data Report: Paleocene-Early Oligocene Calcareous Nannofossil Biostratigraphy, Odp Leg 198 Sites 1209, 1210, and 1211 (Shatsk

Bralower, T.J., Premoli Silva, I., and Malone, M.J. (Eds.) Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results Volume 198 3. DATA REPORT: PALEOCENE–EARLY OLIGOCENE CALCAREOUS NANNOFOSSIL BIOSTRATIGRAPHY, ODP LEG 198 SITES 1209, 1210, AND 1211 (SHATSKY RISE, PACIFIC OCEAN)1 Timothy J. Bralower2 ABSTRACT A relatively complete lower Paleocene to lower Oligocene sequence was recovered from the Southern High of Shatsky Rise at Sites 1209, 1210, and 1211. The sequence consists of nannofossil ooze and clay- rich nannofossil ooze. Samples from these sites have been the target of intensive calcareous nannofossil biostratigraphic investigations. Calcar- 1Bralower, T.J., 2005. Data report: eous nannofossils are moderately preserved in most of the recovered se- Paleocene–early Oligocene calcareous quence, which extends from nannofossil Zones CP1 to CP16. Most nannofossil biostratigraphy, ODP Leg traditional zonal markers are present; however, the rarity and poor pres- 198 Sites 1209, 1210, and 1211 ervation of key species in the uppermost Paleocene and lower Eocene (Shatsky Rise, Pacific Ocean). In inhibits zonal subdivision of part of this sequence. Bralower, T.J., Premoli Silva, I., and Malone, M.J. (Eds.), Proc. ODP, Sci. Results, 198, 1–15 [Online]. Available from World Wide Web: <http:// INTRODUCTION www-odp.tamu.edu/publications/ 198_SR/VOLUME/CHAPTERS/ Ocean Drilling Program Leg 198 addresses the causes and conse- 115.PDF>. [Cited YYYY-MM-DD] 2 quences of Cretaceous and Paleogene global warmth. Eight sites were Department of Geosciences, The Pennsylvania State University, drilled along a broad depth transect on Shatsky Rise, a medium-sized University Park PA 16802, USA. large igneous province in the west-central Pacific. -

Crustacea: Thalassinidea, Brachyura) from Puerto Rico, United States Territory

Bulletin of the Mizunami Fossil Museum, no. 34 (2008), p. 1–15, 6 figs., 1 table. © 2008, Mizunami Fossil Museum New Cretaceous and Cenozoic Decapoda (Crustacea: Thalassinidea, Brachyura) from Puerto Rico, United States Territory Carrie E. Schweitzer1, Jorge Velez-Juarbe2, Michael Martinez3, Angela Collmar Hull1, 4, Rodney M. Feldmann4, and Hernan Santos2 1)Department of Geology, Kent State University Stark Campus, 6000 Frank Ave. NW, North Canton, Ohio, 44720, USA <[email protected]> 2)Department of Geology, University of Puerto Rico, Mayagüez Campus, P. O. Box 9017, Mayagüez, Puerto Rico, 00681 United States Territory <[email protected]> 3)College of Marine Science, University of South Florida, 140 7th Ave. South, St. Petersburg, Florida 33701, USA <[email protected]> 4)Department of Geology, Kent State University, Kent, Ohio 44242, USA <[email protected]> Abstract A large number of recently collected specimens from Puerto Rico has yielded two new species including Palaeoxanthopsis tylotus and Eurytium granulosum, the oldest known occurrence of the latter genus. Cretaceous decapods are reported from Puerto Rico for the first time, and the Cretaceous fauna is similar to that of southern Mexico. Herein is included the first report of Pleistocene decapods from Puerto Rico, which were previously known from other Caribbean localities. The Pleistocene Cardisoma guanhumi is a freshwater crab of the family Gecarcinidae. The freshwater crab families have a poor fossil record; thus, the occurrence is noteworthy and may document dispersal of the crab by humans. Key words: Decapoda, Thalassinidea, Brachyura, Puerto Rico, Cretaceous, Paleogene, Neogene. Introduction than Eocene are not separated by these fault zones and even overlie parts of the fault zones in some areas (Jolly et al., 1998). -

Mollusks and a Crustacean from Early Oligocene Methane-Seep Deposits in the Talara Basin, Northern Peru

Mollusks and a crustacean from early Oligocene methane-seep deposits in the Talara Basin, northern Peru STEFFEN KIEL, FRIDA HYBERTSEN, MATÚŠ HYŽNÝ, and ADIËL A. KLOMPMAKER Kiel, S., Hybertsen, F., Hyžný, M., and Klompmaker, A.A. 2020. Mollusks and a crustacean from early Oligocene methane- seep deposits in the Talara Basin, northern Peru. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 65 (1): 109–138. A total of 25 species of mollusks and crustaceans are reported from Oligocene seep deposits in the Talara Basin in north- ern Peru. Among these, 12 are identified to the species-level, including one new genus, six new species, and three new combinations. Pseudophopsis is introduced for medium-sized, elongate-oval kalenterid bivalves with a strong hinge plate and largely reduced hinge teeth, rough surface sculpture and lacking a pallial sinus. The new species include two bivalves, three gastropods, and one decapod crustacean: the protobranch bivalve Neilo altamirano and the vesicomyid bivalve Pleurophopsis talarensis; among the gastropods, the pyropeltid Pyropelta seca, the provannid Provanna pelada, and the hokkaidoconchid Ascheria salina; the new crustacean is the callianassid Eucalliax capsulasetaea. New combina- tions include the bivalves Conchocele tessaria, Lucinoma zapotalensis, and Pseudophopsis peruviana. Two species are shared with late Eocene to Oligocene seep faunas in Washington state, USA: Provanna antiqua and Colus sekiuensis; the Talara Basin fauna shares only genera, but no species with Oligocene seep fauna in other regions. Further noteworthy aspects of the molluscan fauna include the remarkable diversity of four limpet species, the oldest record of the cocculinid Coccopigya, and the youngest record of the largely seep-restricted genus Ascheria. -

Uncorking the Bottle: What Triggered the Paleocene/Eocene Thermal Maximum Methane Release? Miriame

PALEOCEANOGRAPHY, VOL. 16, NO. 6, PAGES 549-562, DECEMBER 2001 Uncorking the bottle: What triggered the Paleocene/Eocene thermal maximum methane release? MiriamE. Katz,• BenjaminS. Cramer,Gregory S. Mountain,2 Samuel Katz, 3 and KennethG. Miller,1,2 Abstract. The Paleocene/Eocenethermal maximum (PETM) was a time of rapid global warming in both marine and continentalrealms that has been attributed to a massivemethane (CH4) releasefrom marine gas hydrate reservoirs. Previously proposedmechanisms for thismethane release rely on a changein deepwatersource region(s) to increasewater temperatures rapidly enoughto trigger the massivethermal dissociationof gas hydratereservoirs beneath the seafloor.To establish constraintson thermaldissociation, we modelheat flow throughthe sedimentcolumn and showthe effectof the temperature changeon the gashydrate stability zone throughtime. In addition,we provideseismic evidence tied to boreholedata for methanerelease along portions of the U.S. continentalslope; the releasesites are proximalto a buriedMesozoic reef front. Our modelresults, release site locations, published isotopic records, and oceancirculation models neither confirm nor refute thermaldissociation as the triggerfor the PETM methanerelease. In the absenceof definitiveevidence to confirmthermal dissociation,we investigatean altemativehypothesis in which continentalslope failure resulted in a catastrophicmethane release.Seismic and isotopic evidence indicates that Antarctic source deepwater circulation and seafloor erosion caused slope retreatalong -

Clay Minerals at the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum: Interpretations, Limits, and Perspectives

minerals Review Clay Minerals at the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum: Interpretations, Limits, and Perspectives Fabio Tateo Istituto di Geoscienze e Georisorse, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (IGG-CNR) Padova, c/o Dipartimento di Geoscienze, Università di Padova, Via Gradenigo 6, I-35131 Padova, Italy; [email protected] Received: 20 October 2020; Accepted: 26 November 2020; Published: 30 November 2020 Abstract: The Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) was an “extreme” episode of environmental stress that affected the Earth in the past, and it has numerous affinities concerning the rapid increase in the greenhouse effect. It has left several biological, compositional, and sedimentary facies footprints in sedimentary records. Clay minerals are frequently used to decipher environmental effects because they represent their source areas, essentially in terms of climatic conditions and of transport mechanisms (a more or less fast travel, from the bedrocks to the final site of recovery). Clay mineral variations at the PETM have been studied by several authors in terms of climatic and provenance indicators, but also as tracers of more complicated interplay among different factors requiring integrated interpretation (facies sorting, marine circulation, wind transport, early diagenesis, etc.). Clay minerals were also believed to play a role in the recovery of pre-episode climatic conditions after the PETM exordium, by becoming a sink of atmospheric CO2 that is considered a necessary step to switch off the greenhouse hyperthermal effect. This review aims to consider the use of clay minerals made by different authors to study the effects of the PETM and their possible role as effective (simple) proxy tools for environmental reconstructions. -

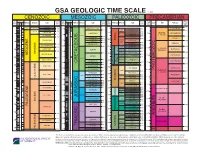

GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE V

GSA GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE v. 4.0 CENOZOIC MESOZOIC PALEOZOIC PRECAMBRIAN MAGNETIC MAGNETIC BDY. AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE PICKS AGE . N PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE EON ERA PERIOD AGES (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) HIST HIST. ANOM. (Ma) ANOM. CHRON. CHRO HOLOCENE 1 C1 QUATER- 0.01 30 C30 66.0 541 CALABRIAN NARY PLEISTOCENE* 1.8 31 C31 MAASTRICHTIAN 252 2 C2 GELASIAN 70 CHANGHSINGIAN EDIACARAN 2.6 Lopin- 254 32 C32 72.1 635 2A C2A PIACENZIAN WUCHIAPINGIAN PLIOCENE 3.6 gian 33 260 260 3 ZANCLEAN CAPITANIAN NEOPRO- 5 C3 CAMPANIAN Guada- 265 750 CRYOGENIAN 5.3 80 C33 WORDIAN TEROZOIC 3A MESSINIAN LATE lupian 269 C3A 83.6 ROADIAN 272 850 7.2 SANTONIAN 4 KUNGURIAN C4 86.3 279 TONIAN CONIACIAN 280 4A Cisura- C4A TORTONIAN 90 89.8 1000 1000 PERMIAN ARTINSKIAN 10 5 TURONIAN lian C5 93.9 290 SAKMARIAN STENIAN 11.6 CENOMANIAN 296 SERRAVALLIAN 34 C34 ASSELIAN 299 5A 100 100 300 GZHELIAN 1200 C5A 13.8 LATE 304 KASIMOVIAN 307 1250 MESOPRO- 15 LANGHIAN ECTASIAN 5B C5B ALBIAN MIDDLE MOSCOVIAN 16.0 TEROZOIC 5C C5C 110 VANIAN 315 PENNSYL- 1400 EARLY 5D C5D MIOCENE 113 320 BASHKIRIAN 323 5E C5E NEOGENE BURDIGALIAN SERPUKHOVIAN 1500 CALYMMIAN 6 C6 APTIAN LATE 20 120 331 6A C6A 20.4 EARLY 1600 M0r 126 6B C6B AQUITANIAN M1 340 MIDDLE VISEAN MISSIS- M3 BARREMIAN SIPPIAN STATHERIAN C6C 23.0 6C 130 M5 CRETACEOUS 131 347 1750 HAUTERIVIAN 7 C7 CARBONIFEROUS EARLY TOURNAISIAN 1800 M10 134 25 7A C7A 359 8 C8 CHATTIAN VALANGINIAN M12 360 140 M14 139 FAMENNIAN OROSIRIAN 9 C9 M16 28.1 M18 BERRIASIAN 2000 PROTEROZOIC 10 C10 LATE