The Impact of Tariff Preference Levels on US Textile and Apparel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

QATAR V. BAHRAIN) REPLY of the STATE of QATAR ______TABLE of CONTENTS PART I - INTRODUCTION CHAPTER I - GENERAL 1 Section 1

CASE CONCERNING MARITIME DELIMITATION AND TERRITORIAL QUESTIONS BETWEEN QATAR AND BAHRAIN (QATAR V. BAHRAIN) REPLY OF THE STATE OF QATAR _____________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I - INTRODUCTION CHAPTER I - GENERAL 1 Section 1. Qatar's Case and Structure of Qatar's Reply Section 2. Deficiencies in Bahrain's Written Pleadings Section 3. Bahrain's Continuing Violations of the Status Quo PART II - THE GEOGRAPHICAL AND HISTORICAL BACKGROUND CHAPTER II - THE TERRITORIAL INTEGRITY OF QATAR Section 1. The Overall Geographical Context Section 2. The Emergence of the Al-Thani as a Political Force in Qatar Section 3. Relations between the Al-Thani and Nasir bin Mubarak Section 4. The 1913 and 1914 Conventions Section 5. The 1916 Treaty Section 6. Al-Thani Authority throughout the Peninsula of Qatar was consolidated long before the 1930s Section 7. The Map Evidence CHAPTER III - THE EXTENT OF THE TERRITORY OF BAHRAIN Section 1. Bahrain from 1783 to 1868 Section 2. Bahrain after 1868 PART III - THE HAWAR ISLANDS AND OTHER TERRITORIAL QUESTIONS CHAPTER IV - THE HAWAR ISLANDS Section 1. Introduction: The Territorial Integrity of Qatar and Qatar's Sovereignty over the Hawar Islands Section 2. Proximity and Qatar's Title to the Hawar Islands Section 3. The Extensive Map Evidence supporting Qatar's Sovereignty over the Hawar Islands Section 4. The Lack of Evidence for Bahrain's Claim to have exercised Sovereignty over the Hawar Islands from the 18th Century to the Present Day Section 5. The Bahrain and Qatar Oil Concession Negotiations between 1925 and 1939 and the Events Leading to the Reversal of British Recognition of Hawar as part of Qatar Section 6. -

United Arab Emirates (Uae)

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: United Arab Emirates, July 2007 COUNTRY PROFILE: UNITED ARAB EMIRATES (UAE) July 2007 COUNTRY اﻟﻌﺮﺑﻴّﺔ اﻟﻤﺘّﺤﺪة (Formal Name: United Arab Emirates (Al Imarat al Arabiyah al Muttahidah Dubai , أﺑﻮ ﻇﺒﻲ (The seven emirates, in order of size, are: Abu Dhabi (Abu Zaby .اﻹﻣﺎرات Al ,ﻋﺠﻤﺎن Ajman , أ مّ اﻟﻘﻴﻮﻳﻦ Umm al Qaywayn , اﻟﺸﺎرﻗﺔ (Sharjah (Ash Shariqah ,دﺑﻲّ (Dubayy) .رأس اﻟﺨﻴﻤﺔ and Ras al Khaymah ,اﻟﻔﺠﻴﺮة Fajayrah Short Form: UAE. اﻣﺮاﺗﻰ .(Term for Citizen(s): Emirati(s أﺑﻮ ﻇﺒﻲ .Capital: Abu Dhabi City Major Cities: Al Ayn, capital of the Eastern Region, and Madinat Zayid, capital of the Western Region, are located in Abu Dhabi Emirate, the largest and most populous emirate. Dubai City is located in Dubai Emirate, the second largest emirate. Sharjah City and Khawr Fakkan are the major cities of the third largest emirate—Sharjah. Independence: The United Kingdom announced in 1968 and reaffirmed in 1971 that it would end its treaty relationships with the seven Trucial Coast states, which had been under British protection since 1892. Following the termination of all existing treaties with Britain, on December 2, 1971, six of the seven sheikhdoms formed the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The seventh sheikhdom, Ras al Khaymah, joined the UAE in 1972. Public holidays: Public holidays other than New Year’s Day and UAE National Day are dependent on the Islamic calendar and vary from year to year. For 2007, the holidays are: New Year’s Day (January 1); Muharram, Islamic New Year (January 20); Mouloud, Birth of Muhammad (March 31); Accession of the Ruler of Abu Dhabi—observed only in Abu Dhabi (August 6); Leilat al Meiraj, Ascension of Muhammad (August 10); first day of Ramadan (September 13); Eid al Fitr, end of Ramadan (October 13); UAE National Day (December 2); Eid al Adha, Feast of the Sacrifice (December 20); and Christmas Day (December 25). -

BAHRAIN and the BATTLE BETWEEN IRAN and SAUDI ARABIA by George Friedman, Strategic Forecasting, Inc

BAHRAIN AND THE BATTLE BETWEEN IRAN AND SAUDI ARABIA By George Friedman, Strategic Forecasting, Inc. The world's attention is focused on Libya, which is now in a state of civil war with the winner far from clear. While crucial for the Libyan people and of some significance to the world's oil markets, in our view, Libya is not the most important event in the Arab world at the moment. The demonstrations in Bahrain are, in my view, far more significant in their implications for the region and potentially for the world. To understand this, we must place it in a strategic context. As STRATFOR has been saying for quite a while, a decisive moment is approaching, with the United States currently slated to withdraw the last of its forces from Iraq by the end of the year. Indeed, we are already at a point where the composition of the 50,000 troops remaining in Iraq has shifted from combat troops to training and support personnel. As it stands now, even these will all be gone by Dec. 31, 2011, provided the United States does not negotiate an extended stay. Iraq still does not have a stable government. It also does not have a military and security apparatus able to enforce the will of the government (which is hardly of one mind on anything) on the country, much less defend the country from outside forces. Filling the Vacuum in Iraq The decision to withdraw creates a vacuum in Iraq, and the question of the wisdom of the original invasion is at this point moot. -

Qatar ν Bahrain in the International Court of Justice at the Hague

Qatar ν Bahrain in the International Court of Justice at The Hague Case concerning Maritime Delimitation and Territorial Questions1 Year 2001 16 March General List No. 87 JUDGMENT ON THE MERITS 1 On 8 July 1991 the Minister for Foreign Affairs of the State of Qatar (here- inafter referred to as "Qatar") filed in the Registry of the Court an Application instituting proceedings against the State of Bahrain (hereinafter referred to as "Bahrain") in respect of certain disputes between the two States relating to "sovereignty over the Hawar islands, sovereign rights over the shoals of Dibal and Qit'at Jaradah, and the delimitation of the maritime areas of the two States". In this Application, Qatar contended that the Court had jurisdiction to entertain the dispute by virtue of two "agreements" concluded between the Parties in December 1987 and December 1990 respectively, the subject and scope of the commitment to the Court's jurisdiction being determined, according to the Applicant, by a formula proposed by Bahrain to Qatar on 26 October 1988 and accepted by Qatar in December 1990 (hereinafter referred to as the "Bahraini formula"). 2 Pursuant to Article 40, paragraph 2, of the Statute of the Court, the Application was forthwith communicated by the Registrar of the Court to the Government of Bahrain; in accordance with paragraph 3 of that Article, all other States entitled to appear before the Court were notified by the Registrar of the Application. 3 By letters addressed to the Registrar on 14 July 1991 and 18 August 1991, Bahrain contested the basis of jurisdiction invoked by Qatar. -

The Gulf States and the Middle East Peace Process: Considerations, Stakes, and Options

ISSUE BRIEF 08.25.20 The Gulf States and the Middle East Peace Process: Considerations, Stakes, and Options Kristian Coates Ulrichsen, Ph.D, Fellow for the Middle East conflict, the Gulf states complied with and INTRODUCTION enforced the Arab League boycott of Israel This issue brief examines where the six until at least 1994 and participated in the nations of the Gulf Cooperation Council— oil embargo of countries that supported 1 Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Israel in the Yom Kippur War of 1973. In Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates 1973, for example, the president of the (UAE)—currently stand in their outlook and UAE, Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, approaches toward the Israeli-Palestinian claimed that “No Arab country is safe from issue. The first section of this brief begins by the perils of the battle with Zionism unless outlining how positions among the six Gulf it plays its role and bears its responsibilities, 2 states have evolved over the three decades in confronting the Israeli enemy.” In since the Madrid Conference of 1991. Section Kuwait, Sheikh Fahd al-Ahmad Al Sabah, a two analyzes the degree to which the six brother of two future Emirs, was wounded Gulf states’ relations with Israel are based while fighting with Fatah in Jordan in 3 on interests, values, or a combination of 1968, while in 1981 the Saudi government both, and how these differ from state to offered to finance the reconstruction of state. Section three details the Gulf states’ Iraq’s Osirak nuclear reactor after it was 4 responses to the peace plan unveiled by destroyed by an Israeli airstrike. -

Nationals of Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Saudi Arabia and U

International Civil Aviation Organization STATUS OF AIRPORTS OPERABILITY AND RESTRICTION INFORMATION - MID REGION Updated on 26 September 2021 Disclaimer This Brief for information purposes only and should not be used as a replacement for airline dispatch and planning tools. All operational stakeholders are requested to consult the most up-to-date AIS publications. The sources of this Brief are the NOTAMs issued by MID States explicitly including COVID-19 related information, States CAA websites and IATA travel center (COVID-19) website. STATE STATUS / RESTRICTION 1. Passengers are not allowed to enter. - This does not apply to: - nationals of Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates; - passengers with a residence permit issued by Bahrain; - passengers with an e-visa obtained before departure; - passengers who can obtain a visa on arrival; - military personnel. 2. Passengers are not allowed to enter if in the past 14 days they have been in or transited through Bangladesh, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Ethiopia, Georgia, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Malawi, Malaysia, Mexico, Mongolia, Mozambique, Myanmar, Namibia, Nepal, Philippines, Slovenia, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Tunisia, Uganda, Ukraine, Viet Nam or Zimbabwe. - This does not apply to: - nationals of Bahrain; - passengers with a residence permit issued by Bahrain. BAHRAIN 3. Passengers must have a negative COVID-19 PCR test taken at most 72 hours before departure. The test result must have a QR code if arriving from Bangladesh, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Ethiopia, Georgia, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Malawi, Malaysia, Mexico, Mongolia, Mozambique, Myanmar, Namibia, Nepal, Philippines, Slovenia, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Tunisia, Uganda, Ukraine, Viet Nam or Zimbabwe. -

Agreement 22 February 1958

page 1| Delimitation Treaties Infobase | accessed on 13/03/2002 Bahrain-Saudi Arabia boundary agreement 22 February 1958 Whereas the regional waters between the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the Government of Bahrain meet together in many places overlooked by their respective coasts, And in view of the royal proclamation issued by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia on the 1st Sha'aban in the year 1368 (corresponding to 28 May 1949) and the ordinance issued by the Government of Bahrain on 5 June 1949 about the exploitation of the sea-bed, And in view of the necessity for an agreement to define the underwater areas belonging to both countries, And in view of the spirit of affection and mutual friendship and the desire of H.M. the King of Saudi Arabia to extend every possible assistance to the Government of Bahrain, The following agreement has been made: First clause 1. The boundary line between the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the Bahrain Government will begin, on the basis of the middle line from point 1, which is situated at the mid-point of the line running between the tip of the Ras al Bar (A) at the southern extremity of Bahrain and Ras Muharra (B) on the coast of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. 2. Then the above-mentioned middle line will extend from point 1 to point 2 situated at the mid-point of the line running between point A and the northern tip of the island of Zakhnuniya (C). 3. Then the line will extend from point 2 to point 3 situated at the mid-point of the line running between point A and the tip of Ras Saiya (D). -

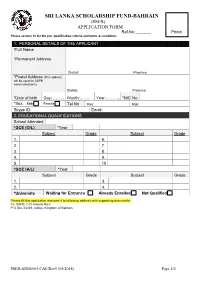

SRI LANKA SCHOLARSHIP FUND-BAHRAIN (SSFB) APPLICATION FORM Ref.No:______Photo Please Section 10 for the Pre- Qualification Criteria and Terms & Conditions

SRI LANKA SCHOLARSHIP FUND-BAHRAIN (SSFB) APPLICATION FORM Ref.No:_______ Photo Please section 10 for the pre- qualification criteria and terms & conditions 1. PERSONAL DETAILS OF THE APPLICANT *Full Name *Permanent Address District: Province: *Postal Address (This address will be used for SSFB communications) District: Province: *Date of birth Day:……… Month:……. Year:……….. *NIC No: *Sex: Male: Female: Tel No Res: Mob: Skype ID: Email: 2. EDUCATIONAL QUALIFICATIONS School Attended *GCE (O/L) *Year Subject Grade Subject Grade 1. 6. 2. 7. 3. 8. 4. 9. 5. 10 *GCE (A/L) *Year Subject Grade Subject Grade 1. 3. 2. 4. *University Waiting for Entrance Already Enrolled Not Qualified Please fill this application and post it to following address with supporting documents: To: SSFB, C/O Ahmed Rizvi P O Box 26349, Adliya, Kingdom of Bahrain SSFB-ADM-003-CAF/Rev9 (05/2018) Page 1/4 SRI LANKA SCHOLARSHIP FUND-BAHRAIN (SSFB) APPLICATION FORM 3. COURSE DETAILS AND EXPENSES *Course Name Contents / Subjects Note : Specify Part 1, Part II, Finals etc. Require supporting course prospect attached or submitted at interview as proof *Start Date DD-MM-YY: *Duration (In months): Describe course schedule if not Continuous Detailed Fund Requirement Breakdown (Additional space available below, if required) Year Month Registration Tuition fees Other Fees Examination Fees Other (specify) Year Month Registration Tuition fees Other Fees Examination Fees Other (specify) Year Month Registration Tuition fees Other Fees Examination Fees Other (specify) Year Month Registration Tuition fees Other Fees Examination Fees Other (specify) SSFB-ADM-003-CAF/Rev9 (05/2018) Page 2/4 SRI LANKA SCHOLARSHIP FUND-BAHRAIN (SSFB) APPLICATION FORM Describe if payment schedule if not continuous Own Residence * From where do you *Distance from Accommodation Travel to the Institute Boarding/Relative to Institute (in KM) Expected Assistance Registration Course Exam Food/ Transport from Scholarship for Fee Fee Lodging 4. -

Bahrain, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Qatar: 100 Days of Pointless Arab Self-Destructiveness and Counting Anthony H

Bahrain, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Qatar: 100 Days of Pointless Arab Self-Destructiveness and Counting Anthony H. Cordesman No American can criticize Arab states without first acknowledging that the United States has made a host of mistakes of its own in dealing with nations like Iraq, Libya, Syria, and Yemen. The fact remains, however, that the word "Arab" has come to be a synonym for disunity, dysfunctional, and self-destructive. Regardless of issuing of one ambitious "Arab" plan for new coalitions after another, the reality is failed internal leadership and development, pointless feuding between Arab states, and an inability to cooperate and coordinate when common action is most needed. The most immediate example is the series of efforts by Bahrain, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE to isolate, embargo, and boycott Qatar. Some 100 days have passed since they issued some 13 broad, categorical, and poorly defined demands that Qatar change its behavior. These demands may or may not have been reduced to six equally badly phrased and vague statements, but this is unclear. There have been some faltering steps towards negotiation, and President Trump (after helping to trigger the embargo) has made a serious effort at mediation. So far, however, the crisis continues, along with references to "mad dogs" in the Arab League, and new sets of mutual accusations. The end result has done little more than revive the long history of self-destructive divisiveness among the Arab states. Once again, Saudi Arabia and the UAE are bickering with Qatar. Egypt is putting repression and counterterrorism before stability and development. -

Qatar: Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy

Qatar: Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy Updated August 27, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R44533 SUMMARY R44533 Qatar: Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy August 27, 2021 The State of Qatar, a small Arab Gulf monarchy which has about 300,000 citizens in a total population of about 2.4 million, has employed its ample financial resources to exert Kenneth Katzman regional influence, often independent of the other members of the Gulf Cooperation Specialist in Middle Council (GCC: Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar, United Arab Emirates (UAE), Bahrain, and Eastern Affairs Oman) alliance. Qatar has fostered a close defense and security alliance with the United States and has maintained ties to a wide range of actors who are often at odds with each other, including Sunni Islamists, Iran and Iran-backed groups, and Israeli officials. Qatar’s support for regional Muslim Brotherhood organizations and its Al Jazeera media network have contributed to a backlash against Qatar led by fellow GCC states Saudi Arabia and the UAE. In June 2017, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Bahrain, joined by Egypt and a few other governments, severed relations with Qatar and imposed limits on the entry and transit of Qatari nationals and vessels in their territories, waters, and airspace. The Trump Administration sought a resolution of the dispute, in part because the rift was hindering U.S. efforts to formalize a “Middle East Strategic Alliance” of the United States, the GCC, and other Sunni-led countries in the region to counter Iran. Qatar has countered the Saudi-led pressure with new arms purchases and deepening relations with Turkey and Iran. -

About North Cyprus Cyprus Lies in the Eastern Mediterranean, Only Four

About North Cyprus Cyprus lies in the Eastern Mediterranean, only four hours flying time from central Europe. Its nearest neighbour is Turkey, just 40 miles north. It’s geography shares many characteristics with mainland Turkey. Cyprus is the third largest island in the Mediterranean. It is smaller than Sicily and Sardinia and larger than Corsica and Crete. The total area of the island is 3584 sq. miles. (9250 sq. kilometers) Northern Cyprus has four major towns, the capital being Lefkosa (Nicosia), which serves as the main administration and business centre. The other main towns are Magosa (Famagusta), the country's principal port; Girne (Kyrenia), the main tourist centre well known for its ancient harbour, and Guzelyurt the centre of the citrus fruit industry. British interest in the island dates back to the 12th century and continues to the present day, with many British ways adopted by the government of the Northern Cyprus. English is widely spoken and driving is on the left hand side of the road. Cyprus has a long vibrant history, with a perfect climate and warm hospitality. It has been a British playground for many years for relaxation, water sports and the excitement of exploring its beautiful coastline. Northern Cyprus is a rich source of archaeological sites and medieval castles. It enjoys over 300 days of uninterrupted sunshine, crystal clear Mediterranean seas with a beautiful unspoiled landscape and uncrowded beaches. Airports in Cyprus There are 3 airports flying to the Mediterranean Island of Cyprus. You can fly to North Cyprus through the International Airport Ercan (ECN), which is located near Nicosia and is approximately 40km from Kyrenia/Girne. -

Martime Delimitation and Territorial Questions Between Qatar and Bahrain

Denver Journal of International Law & Policy Volume 26 Number 4 Summer Article 8 May 2020 Martime Delimitation and Territorial Questions between Qatar and Bahrain Marla C. Reichel Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/djilp Recommended Citation Marla C. Reichel, Martime Delimitation and Territorial Questions between Qatar and Bahrain, 26 Denv. J. Int'l L. & Pol'y 725 (1998). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denver Journal of International Law & Policy by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. Maritime Delimitation and Territorial Questions Between Qatar and Bahrain Marla C. Reichel "IT]here is no State so powerful that it may not some time need the help of others outside itself, either for purposes of trade, or even to ward off the forces of many foreign nations united against it... [E]ven the most powerful peoples and sovereigns seek alliances, which are quite devoid of significance according to the point of view of those who confine law within the boundaries of States. Most true is the saying that, all things are uncertain the moment [one] depart[s] from the law." Hugo Grotius in 1625, Founding Father of International Law I. INTRODUCTION The Case Concerning Maritime Delimitation and Territorial Ques- tions Between Qatar and Bahrain' poses two main issues to the Inter- national Court of Justice: those of admissibility and jurisdiction. Ini- tially, the Court has to decide whether Qatar followed proper procedure by unilaterally admitting the dispute for adjudication.