Lessons from Lebanon, Bahrain, Syria, and Iraq

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of Tariff Preference Levels on US Textile and Apparel

Office of Industries Working Paper ID-053 September 2018 The Impact of Tariff Preference Levels on U.S. Textile and Apparel Trade Mahnaz Khan Abstract Certain U.S. bilateral or multilateral free trade agreements contain tariff preference levels (TPLs) that permit a limited quantity of specified finished textile and/or apparel goods to enter the U.S. market at preferential duty rates despite not meeting the agreement’s required tariff shift rules. This article seeks to examine the effect of TPL provisions that have expired, or will expire in 2018, on U.S. textile and apparel imports and exports from certain FTA partners, including Bahrain, Nicaragua and Costa Rica (under CAFTA-DR), Morocco, Oman, and Singapore. It will discuss import and export trends after TPL implementation and in some cases, TPL expiration, in the context of an FTA partners’ industry structure and competitiveness as a U.S. textile and apparel supplier. Such trends vary widely across countries, and analysis of the factors influencing these trade flows suggests that the effectiveness of TPLs is dependent upon myriad factors, including the structure of the partner country’s textile and apparel sector, the country’s competitiveness as a U.S. supplier, and existence or absence of relationships with U.S. textile firms. Disclaimer: Office of Industries working papers are the result of the ongoing professional research of USITC staff and solely represent the opinions and professional research of individual authors. These papers do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. International Trade Commission or any of its individual Commissioners. The Impact of Tariff Preference Levels on U.S. -

QATAR V. BAHRAIN) REPLY of the STATE of QATAR ______TABLE of CONTENTS PART I - INTRODUCTION CHAPTER I - GENERAL 1 Section 1

CASE CONCERNING MARITIME DELIMITATION AND TERRITORIAL QUESTIONS BETWEEN QATAR AND BAHRAIN (QATAR V. BAHRAIN) REPLY OF THE STATE OF QATAR _____________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I - INTRODUCTION CHAPTER I - GENERAL 1 Section 1. Qatar's Case and Structure of Qatar's Reply Section 2. Deficiencies in Bahrain's Written Pleadings Section 3. Bahrain's Continuing Violations of the Status Quo PART II - THE GEOGRAPHICAL AND HISTORICAL BACKGROUND CHAPTER II - THE TERRITORIAL INTEGRITY OF QATAR Section 1. The Overall Geographical Context Section 2. The Emergence of the Al-Thani as a Political Force in Qatar Section 3. Relations between the Al-Thani and Nasir bin Mubarak Section 4. The 1913 and 1914 Conventions Section 5. The 1916 Treaty Section 6. Al-Thani Authority throughout the Peninsula of Qatar was consolidated long before the 1930s Section 7. The Map Evidence CHAPTER III - THE EXTENT OF THE TERRITORY OF BAHRAIN Section 1. Bahrain from 1783 to 1868 Section 2. Bahrain after 1868 PART III - THE HAWAR ISLANDS AND OTHER TERRITORIAL QUESTIONS CHAPTER IV - THE HAWAR ISLANDS Section 1. Introduction: The Territorial Integrity of Qatar and Qatar's Sovereignty over the Hawar Islands Section 2. Proximity and Qatar's Title to the Hawar Islands Section 3. The Extensive Map Evidence supporting Qatar's Sovereignty over the Hawar Islands Section 4. The Lack of Evidence for Bahrain's Claim to have exercised Sovereignty over the Hawar Islands from the 18th Century to the Present Day Section 5. The Bahrain and Qatar Oil Concession Negotiations between 1925 and 1939 and the Events Leading to the Reversal of British Recognition of Hawar as part of Qatar Section 6. -

How Many People Live in Manama? and How Many Property Owners Are There? Who Is Allowed to Enter the City? and What’S the Density of Its Population?

How many people live in Manama? And how many property owners are there? Who is allowed to enter the city? And what’s the density of its population? Ask the same questions for this “Bahrain” island over here! S a m e s c a l e ! They call this a private That’s OK. But just be … and did the property (owned by a reminded that it’s twice owner of it member of the ruling family) as big as Sadad village… pay for it?! This is Malkiyya. How many times of Malkiyya’s population can this area accommodate? But sorry… Not for sale! Owned by a ruling family member! Legal?!! What’s this?! It’s the King’s favorite property! It’s the size of Malkiyya, Karzakkan, Sadad and Shahrakkan together! What’s in there? Here you go… That’s right… An island! Look for the yacht… And note the size of it… A golf course… A horse track… … and the main facility Just to the near South of Bilaj Al-Jaza’er A’ALI Shahrakkan & part of Zallaq… The entire area is owned by Al-Khalifa Compare the size and color of the two areas! Southern part of Bahrain. Thinking of going there is trespassing! And hey! What’s that spot?! That’s THAT! Nasser Bin Hamad’s manor! How did he get it?!!! In the middle of nowhere… Rumaitha Palace (Hamad Bin Issa manor “one of them”) UOB F1 “Small” mansion! A little bit a bigger one. Compare the size of it against UOB and F1 track Constitution of Bahrain Article 11 [Natural Resources] All natural wealth and resources are State property. -

United Arab Emirates (Uae)

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: United Arab Emirates, July 2007 COUNTRY PROFILE: UNITED ARAB EMIRATES (UAE) July 2007 COUNTRY اﻟﻌﺮﺑﻴّﺔ اﻟﻤﺘّﺤﺪة (Formal Name: United Arab Emirates (Al Imarat al Arabiyah al Muttahidah Dubai , أﺑﻮ ﻇﺒﻲ (The seven emirates, in order of size, are: Abu Dhabi (Abu Zaby .اﻹﻣﺎرات Al ,ﻋﺠﻤﺎن Ajman , أ مّ اﻟﻘﻴﻮﻳﻦ Umm al Qaywayn , اﻟﺸﺎرﻗﺔ (Sharjah (Ash Shariqah ,دﺑﻲّ (Dubayy) .رأس اﻟﺨﻴﻤﺔ and Ras al Khaymah ,اﻟﻔﺠﻴﺮة Fajayrah Short Form: UAE. اﻣﺮاﺗﻰ .(Term for Citizen(s): Emirati(s أﺑﻮ ﻇﺒﻲ .Capital: Abu Dhabi City Major Cities: Al Ayn, capital of the Eastern Region, and Madinat Zayid, capital of the Western Region, are located in Abu Dhabi Emirate, the largest and most populous emirate. Dubai City is located in Dubai Emirate, the second largest emirate. Sharjah City and Khawr Fakkan are the major cities of the third largest emirate—Sharjah. Independence: The United Kingdom announced in 1968 and reaffirmed in 1971 that it would end its treaty relationships with the seven Trucial Coast states, which had been under British protection since 1892. Following the termination of all existing treaties with Britain, on December 2, 1971, six of the seven sheikhdoms formed the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The seventh sheikhdom, Ras al Khaymah, joined the UAE in 1972. Public holidays: Public holidays other than New Year’s Day and UAE National Day are dependent on the Islamic calendar and vary from year to year. For 2007, the holidays are: New Year’s Day (January 1); Muharram, Islamic New Year (January 20); Mouloud, Birth of Muhammad (March 31); Accession of the Ruler of Abu Dhabi—observed only in Abu Dhabi (August 6); Leilat al Meiraj, Ascension of Muhammad (August 10); first day of Ramadan (September 13); Eid al Fitr, end of Ramadan (October 13); UAE National Day (December 2); Eid al Adha, Feast of the Sacrifice (December 20); and Christmas Day (December 25). -

BAHRAIN and the BATTLE BETWEEN IRAN and SAUDI ARABIA by George Friedman, Strategic Forecasting, Inc

BAHRAIN AND THE BATTLE BETWEEN IRAN AND SAUDI ARABIA By George Friedman, Strategic Forecasting, Inc. The world's attention is focused on Libya, which is now in a state of civil war with the winner far from clear. While crucial for the Libyan people and of some significance to the world's oil markets, in our view, Libya is not the most important event in the Arab world at the moment. The demonstrations in Bahrain are, in my view, far more significant in their implications for the region and potentially for the world. To understand this, we must place it in a strategic context. As STRATFOR has been saying for quite a while, a decisive moment is approaching, with the United States currently slated to withdraw the last of its forces from Iraq by the end of the year. Indeed, we are already at a point where the composition of the 50,000 troops remaining in Iraq has shifted from combat troops to training and support personnel. As it stands now, even these will all be gone by Dec. 31, 2011, provided the United States does not negotiate an extended stay. Iraq still does not have a stable government. It also does not have a military and security apparatus able to enforce the will of the government (which is hardly of one mind on anything) on the country, much less defend the country from outside forces. Filling the Vacuum in Iraq The decision to withdraw creates a vacuum in Iraq, and the question of the wisdom of the original invasion is at this point moot. -

The Dilmun Burial Mounds of Bahrain

DigIt Volume 2, Issue 1 Journal of the Flinders Archaeological Society June 2014 ISSN 2203-1898 Contents Original research articles The Dead Beneath the Floor: The use of space for burial in the Dominican Blackfriary, Trim, Co. Meath, Ireland 2 Emma M. Lagan The Dilmun Burial Mounds of Bahrain: An introduction to the site and the importance of awareness raising towards 12 successful preservation Melanie Münzner New Approaches to the Celtic Urbanisation Process 19 Clara Filet Yup’ik Eskimo Kayak Miniatures: Preliminary notes on kayaks from the Nunalleq site 28 Celeste Jordan The Contribution of Chert Knapped Stone Studies at Çatalhöyük to notions of territory and group mobility in 34 prehistoric Central Anatolia Sonia Ostaptchouk Figuring Out the Figurines: Towards the interpretation of Neolithic corporeality in the Republic of Macedonia 49 Goce Naumov Research essay Inert, Inanimate, Invaluable: How stone artefact analyses have informed of Australia’s past 61 Simon Munt Field reports Kani Shaie Archaeological Project: New fieldwork in Iraqi Kurdistan 66 Steve Rennette A Tale of Two Cities 68 Ilona Bartsch Dig It dialogue An Interview with Brian Fagan 69 Jordan Ralph Reviews Spencer and Gillen: A journey through Aboriginal Australia 71 Gary Jackson The Future’s as Bright as the Smiles: National Archaeology Student Conference 2014 73 Chelsea Colwell-Pasch ArchSoc news 76 Journal profile: Chronika DigIt78 Editorial President’s Address What an exciting and transformative 6 months for Dig It! Our I would firstly like to say welcome to our new and continuing Journal simultaneously became peer-reviewed, international, members for 2014. We look forward to delivering an outstanding and larger – including more pages and including more people service of both professional development and social networking into the editorial process. -

Country Advice

Country Advice Bahrain Bahrain – BHR39737 – 14 February 2011 Protests – Treatment of Protesters – Treatment of Shias – Protests in Australia Returnees – 30 January 2012 1. Please provide details of the protest(s) which took place in Bahrain on 14 February 2011, including the exact location of protest activities, the time the protest activities started, the sequence of events, the time the protest activities had ended on the day, the nature of the protest activities, the number of the participants, the profile of the participants and the reaction of the authorities. The vast majority of protesters involved in the 2011 uprising in Bahrain were Shia Muslims calling for political reforms.1 According to several sources, the protest movement was led by educated and politically unaffiliated youth.2 Like their counterparts in other Arab countries, they used modern technology, including social media networks to call for demonstrations and publicise their demands.3 The demands raised during the protests enjoyed, at least initially, a large degree of popular support that crossed religious, sectarian and ethnic lines.4 On 29 June 2011 Bahrain‟s King Hamad issued a decree establishing the Bahrain Independent Commission of Investigation (BICI) which was mandated to investigate the events occurring in Bahrain in February and March 2011.5 The BICI was headed by M. Cherif Bassiouni and four other internationally recognised human rights experts.6 1 Amnesty International 2011, Briefing paper – Bahrain: A human rights crisis, 21 April, p.2 http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/asset/MDE11/019/2011/en/40555429-a803-42da-a68d- -

Qatar ν Bahrain in the International Court of Justice at the Hague

Qatar ν Bahrain in the International Court of Justice at The Hague Case concerning Maritime Delimitation and Territorial Questions1 Year 2001 16 March General List No. 87 JUDGMENT ON THE MERITS 1 On 8 July 1991 the Minister for Foreign Affairs of the State of Qatar (here- inafter referred to as "Qatar") filed in the Registry of the Court an Application instituting proceedings against the State of Bahrain (hereinafter referred to as "Bahrain") in respect of certain disputes between the two States relating to "sovereignty over the Hawar islands, sovereign rights over the shoals of Dibal and Qit'at Jaradah, and the delimitation of the maritime areas of the two States". In this Application, Qatar contended that the Court had jurisdiction to entertain the dispute by virtue of two "agreements" concluded between the Parties in December 1987 and December 1990 respectively, the subject and scope of the commitment to the Court's jurisdiction being determined, according to the Applicant, by a formula proposed by Bahrain to Qatar on 26 October 1988 and accepted by Qatar in December 1990 (hereinafter referred to as the "Bahraini formula"). 2 Pursuant to Article 40, paragraph 2, of the Statute of the Court, the Application was forthwith communicated by the Registrar of the Court to the Government of Bahrain; in accordance with paragraph 3 of that Article, all other States entitled to appear before the Court were notified by the Registrar of the Application. 3 By letters addressed to the Registrar on 14 July 1991 and 18 August 1991, Bahrain contested the basis of jurisdiction invoked by Qatar. -

The Gulf States and the Middle East Peace Process: Considerations, Stakes, and Options

ISSUE BRIEF 08.25.20 The Gulf States and the Middle East Peace Process: Considerations, Stakes, and Options Kristian Coates Ulrichsen, Ph.D, Fellow for the Middle East conflict, the Gulf states complied with and INTRODUCTION enforced the Arab League boycott of Israel This issue brief examines where the six until at least 1994 and participated in the nations of the Gulf Cooperation Council— oil embargo of countries that supported 1 Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Israel in the Yom Kippur War of 1973. In Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates 1973, for example, the president of the (UAE)—currently stand in their outlook and UAE, Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, approaches toward the Israeli-Palestinian claimed that “No Arab country is safe from issue. The first section of this brief begins by the perils of the battle with Zionism unless outlining how positions among the six Gulf it plays its role and bears its responsibilities, 2 states have evolved over the three decades in confronting the Israeli enemy.” In since the Madrid Conference of 1991. Section Kuwait, Sheikh Fahd al-Ahmad Al Sabah, a two analyzes the degree to which the six brother of two future Emirs, was wounded Gulf states’ relations with Israel are based while fighting with Fatah in Jordan in 3 on interests, values, or a combination of 1968, while in 1981 the Saudi government both, and how these differ from state to offered to finance the reconstruction of state. Section three details the Gulf states’ Iraq’s Osirak nuclear reactor after it was 4 responses to the peace plan unveiled by destroyed by an Israeli airstrike. -

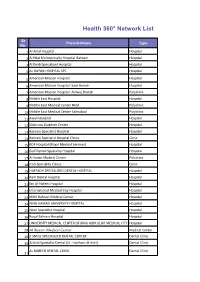

Health 360° Network List

Health 360° Network List Sr ProviderName Type No. 1 Al Amal Hospital Hospital 2 Al Hilal Multispecialty Hospital-Bahrain Hospital 3 Al Kindi Specialised Hospital Hospital 4 AL RAYAN HOSPITAL SPC Hospital 5 American Mission Hospital Hospital 6 American Mission Hospital -Saar Branch Hospital 7 American Mission Hospital -Amwaj Branch Polyclinic 8 Middle East Hospital Hospital 9 Middle East Medical Center Hidd Polyclinic 10 Middle East Medical Center Salmabad Polyclinic 11 Awali Hospital Hospital 12 Mahroos Diabetes Center Hospital 13 Bahrain Specialist Hospital Hospital 14 Bahrain Specialist Hospital Clinics Clinic 15 BDF Hospital (Royal Medical Services) Hospital 16 Gulf Dental Speciality Hospital Hospital 17 Al Senan Medical Center Polyclinic 18 Irish Speciality Clinics Clinic 19 HAFFADH SPECIALISED DENTAL HOSPITAL Hospital 20 Ram Dental Hospital Hospital 21 Ibn Al-Nafees Hospital Hospital 22 International Medical City Hospital Hospital 23 KIMS Bahrain Medical Center Hospital 24 KING HAMAD UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL Hospital 25 Noor Specialist Hospital Hospital 26 Royal Bahrain Hospital Hospital 27 UNIVERSITY MEDICAL CENTER OF KING ABDULLAH MEDICAL CITY Hospital 28 Al Bayan Medical Center Medical Center 29 2 SMILE SPECIALIZED DENTAL CENTER Dental Clinic 30 Al Jishi Specialist Dental (Dr. Haitham Al-Jishi) Dental Clinic AL RABEEH DENTAL CLINIC Dental Clinic 31 New Al-Rabeeh Gate Dental Clinic Dental Clinic 32 33 Dr.Balqees Abdulla Tawash Dental Center Dental Clinic 34 CERAM DENTAL SPECIALIST CENTER Dental Clinic 35 Dr. Ali Mattar Clinic Dental Clinic 36 Dr. Amal Al Samak Dental Centre Dental Clinic 37 Dr. Lamya Mahmood Clinic Dental Clinic 38 Dr. Lamya Mahmood Clinic Dental Clinic 39 Dr. Mariam Habib Dental Clinic Dental Clinic 40 Dr. -

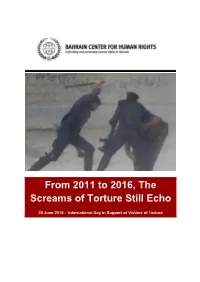

From 2011 to 2016, the Screams of Torture Still Echo

From 2011 to 2016, The Screams of Torture Still Echo 26 June 2016 - International Day in Support of Victims of Torture From 2011 to 2016, The Screams of Torture Still Echo Copyright © 2016, Bahrain Center for Human Rights (BCHR). All rights reserved. Publication of this report would not have been possible without the generous support from the Arab Human Rights Fund (AHRF), European Endowment for Democracy (EED) and the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) to which the BCHR wishes to express its sincere gratitude. Bahrain Center for Human Rights 2 From 2011 to 2016, The Screams of Torture Still Echo About Us The Bahrain Center for Human Rights (BCHR) is a non-profit, non-governmental organization, registered with the Bahraini Ministry of Labor and Social Services since July 2002. Despite an order by the authorities in November 2004 to close down, BCHR is still functioning after gaining a wide local and international support for its struggle to promote human rights in Bahrain. The vast majority of our operations are carried out in Bahrain, while a small office in exile, founded in 2011, is maintained in Copenhagen, Denmark, to coordinate our international advocacy program. For more than 13 years, BCHR has carried out numerous projects, including advocacy, online security training, workshops, seminars, media campaigns and reporting to UN mechanisms and international NGOs. BCHR has also participated in many regional and international conferences and workshops in addition to testifying in national parliaments across Europe, the EU parliament, and the United States Congress. BCHR has received a number of awards for its efforts to promote democracy and human rights in Bahrain. -

Nationals of Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Saudi Arabia and U

International Civil Aviation Organization STATUS OF AIRPORTS OPERABILITY AND RESTRICTION INFORMATION - MID REGION Updated on 26 September 2021 Disclaimer This Brief for information purposes only and should not be used as a replacement for airline dispatch and planning tools. All operational stakeholders are requested to consult the most up-to-date AIS publications. The sources of this Brief are the NOTAMs issued by MID States explicitly including COVID-19 related information, States CAA websites and IATA travel center (COVID-19) website. STATE STATUS / RESTRICTION 1. Passengers are not allowed to enter. - This does not apply to: - nationals of Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates; - passengers with a residence permit issued by Bahrain; - passengers with an e-visa obtained before departure; - passengers who can obtain a visa on arrival; - military personnel. 2. Passengers are not allowed to enter if in the past 14 days they have been in or transited through Bangladesh, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Ethiopia, Georgia, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Malawi, Malaysia, Mexico, Mongolia, Mozambique, Myanmar, Namibia, Nepal, Philippines, Slovenia, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Tunisia, Uganda, Ukraine, Viet Nam or Zimbabwe. - This does not apply to: - nationals of Bahrain; - passengers with a residence permit issued by Bahrain. BAHRAIN 3. Passengers must have a negative COVID-19 PCR test taken at most 72 hours before departure. The test result must have a QR code if arriving from Bangladesh, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Ethiopia, Georgia, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Malawi, Malaysia, Mexico, Mongolia, Mozambique, Myanmar, Namibia, Nepal, Philippines, Slovenia, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Tunisia, Uganda, Ukraine, Viet Nam or Zimbabwe.