The Dilmun Burial Mounds of Bahrain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Many People Live in Manama? and How Many Property Owners Are There? Who Is Allowed to Enter the City? and What’S the Density of Its Population?

How many people live in Manama? And how many property owners are there? Who is allowed to enter the city? And what’s the density of its population? Ask the same questions for this “Bahrain” island over here! S a m e s c a l e ! They call this a private That’s OK. But just be … and did the property (owned by a reminded that it’s twice owner of it member of the ruling family) as big as Sadad village… pay for it?! This is Malkiyya. How many times of Malkiyya’s population can this area accommodate? But sorry… Not for sale! Owned by a ruling family member! Legal?!! What’s this?! It’s the King’s favorite property! It’s the size of Malkiyya, Karzakkan, Sadad and Shahrakkan together! What’s in there? Here you go… That’s right… An island! Look for the yacht… And note the size of it… A golf course… A horse track… … and the main facility Just to the near South of Bilaj Al-Jaza’er A’ALI Shahrakkan & part of Zallaq… The entire area is owned by Al-Khalifa Compare the size and color of the two areas! Southern part of Bahrain. Thinking of going there is trespassing! And hey! What’s that spot?! That’s THAT! Nasser Bin Hamad’s manor! How did he get it?!!! In the middle of nowhere… Rumaitha Palace (Hamad Bin Issa manor “one of them”) UOB F1 “Small” mansion! A little bit a bigger one. Compare the size of it against UOB and F1 track Constitution of Bahrain Article 11 [Natural Resources] All natural wealth and resources are State property. -

Country Advice

Country Advice Bahrain Bahrain – BHR39737 – 14 February 2011 Protests – Treatment of Protesters – Treatment of Shias – Protests in Australia Returnees – 30 January 2012 1. Please provide details of the protest(s) which took place in Bahrain on 14 February 2011, including the exact location of protest activities, the time the protest activities started, the sequence of events, the time the protest activities had ended on the day, the nature of the protest activities, the number of the participants, the profile of the participants and the reaction of the authorities. The vast majority of protesters involved in the 2011 uprising in Bahrain were Shia Muslims calling for political reforms.1 According to several sources, the protest movement was led by educated and politically unaffiliated youth.2 Like their counterparts in other Arab countries, they used modern technology, including social media networks to call for demonstrations and publicise their demands.3 The demands raised during the protests enjoyed, at least initially, a large degree of popular support that crossed religious, sectarian and ethnic lines.4 On 29 June 2011 Bahrain‟s King Hamad issued a decree establishing the Bahrain Independent Commission of Investigation (BICI) which was mandated to investigate the events occurring in Bahrain in February and March 2011.5 The BICI was headed by M. Cherif Bassiouni and four other internationally recognised human rights experts.6 1 Amnesty International 2011, Briefing paper – Bahrain: A human rights crisis, 21 April, p.2 http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/asset/MDE11/019/2011/en/40555429-a803-42da-a68d- -

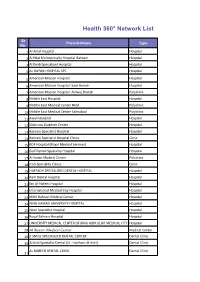

Health 360° Network List

Health 360° Network List Sr ProviderName Type No. 1 Al Amal Hospital Hospital 2 Al Hilal Multispecialty Hospital-Bahrain Hospital 3 Al Kindi Specialised Hospital Hospital 4 AL RAYAN HOSPITAL SPC Hospital 5 American Mission Hospital Hospital 6 American Mission Hospital -Saar Branch Hospital 7 American Mission Hospital -Amwaj Branch Polyclinic 8 Middle East Hospital Hospital 9 Middle East Medical Center Hidd Polyclinic 10 Middle East Medical Center Salmabad Polyclinic 11 Awali Hospital Hospital 12 Mahroos Diabetes Center Hospital 13 Bahrain Specialist Hospital Hospital 14 Bahrain Specialist Hospital Clinics Clinic 15 BDF Hospital (Royal Medical Services) Hospital 16 Gulf Dental Speciality Hospital Hospital 17 Al Senan Medical Center Polyclinic 18 Irish Speciality Clinics Clinic 19 HAFFADH SPECIALISED DENTAL HOSPITAL Hospital 20 Ram Dental Hospital Hospital 21 Ibn Al-Nafees Hospital Hospital 22 International Medical City Hospital Hospital 23 KIMS Bahrain Medical Center Hospital 24 KING HAMAD UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL Hospital 25 Noor Specialist Hospital Hospital 26 Royal Bahrain Hospital Hospital 27 UNIVERSITY MEDICAL CENTER OF KING ABDULLAH MEDICAL CITY Hospital 28 Al Bayan Medical Center Medical Center 29 2 SMILE SPECIALIZED DENTAL CENTER Dental Clinic 30 Al Jishi Specialist Dental (Dr. Haitham Al-Jishi) Dental Clinic AL RABEEH DENTAL CLINIC Dental Clinic 31 New Al-Rabeeh Gate Dental Clinic Dental Clinic 32 33 Dr.Balqees Abdulla Tawash Dental Center Dental Clinic 34 CERAM DENTAL SPECIALIST CENTER Dental Clinic 35 Dr. Ali Mattar Clinic Dental Clinic 36 Dr. Amal Al Samak Dental Centre Dental Clinic 37 Dr. Lamya Mahmood Clinic Dental Clinic 38 Dr. Lamya Mahmood Clinic Dental Clinic 39 Dr. Mariam Habib Dental Clinic Dental Clinic 40 Dr. -

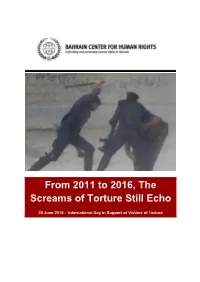

From 2011 to 2016, the Screams of Torture Still Echo

From 2011 to 2016, The Screams of Torture Still Echo 26 June 2016 - International Day in Support of Victims of Torture From 2011 to 2016, The Screams of Torture Still Echo Copyright © 2016, Bahrain Center for Human Rights (BCHR). All rights reserved. Publication of this report would not have been possible without the generous support from the Arab Human Rights Fund (AHRF), European Endowment for Democracy (EED) and the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) to which the BCHR wishes to express its sincere gratitude. Bahrain Center for Human Rights 2 From 2011 to 2016, The Screams of Torture Still Echo About Us The Bahrain Center for Human Rights (BCHR) is a non-profit, non-governmental organization, registered with the Bahraini Ministry of Labor and Social Services since July 2002. Despite an order by the authorities in November 2004 to close down, BCHR is still functioning after gaining a wide local and international support for its struggle to promote human rights in Bahrain. The vast majority of our operations are carried out in Bahrain, while a small office in exile, founded in 2011, is maintained in Copenhagen, Denmark, to coordinate our international advocacy program. For more than 13 years, BCHR has carried out numerous projects, including advocacy, online security training, workshops, seminars, media campaigns and reporting to UN mechanisms and international NGOs. BCHR has also participated in many regional and international conferences and workshops in addition to testifying in national parliaments across Europe, the EU parliament, and the United States Congress. BCHR has received a number of awards for its efforts to promote democracy and human rights in Bahrain. -

Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain (ADHRB)

Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain (ADHRB) and Bahrain Center Cultural Society (BCCS) For consideration at the 27th session of the UN working group in April-May 2017 22 September 2016 1. ADHRB is a non-profit organization that fosters awareness of and support for democracy and human rights in Bahrain and the Middle East. 2. ADHRB’s reporting is based primarily on its United Nations (UN) complaint program, by which it works directly with victims of human rights violations, their family members or their lawyers on the ground in the region to document evidence of abuses and submit this evidence to the UN Special Procedures. ADHRB has repeatedly requested permission to formally visit Bahrain in order to consult with government officials, national human rights mechanisms, and our independent civil society partners on the ground, regarding issues relating to the UPR process, but has been so far denied access. As yet, the Government of Bahrain has declined to cooperate with ADHRB on any level. 3. BCCS is Bahraini cultural center and advocacy organization based in Berlin, Germany. 4. ADHRB and BCCS welcome the opportunity to contribute to the third cycle of the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) of Bahrain. This submission focuses on Bahrain’s compliance with its second-cycle recommendations to take measures to meet the aspirations of victims of discrimination and protect ethnic and religious groups from abuse. Introduction 5. In its second UPR cycle, the Government of Bahrain fully supported recommendations 115.70 (Belgium) and 115.93 (Canada) concerning efforts to meet the aspirations of the victims of discrimination and the protection of ethnic and religious communities. -

Zallaq-Springs-Brochure.Pdf

Zallaq Springs waterfront destination has been inspired by ideas of Japanese Zen gardens, and provides an avant-garde central point for everyone to meet, relax, eat, socialize and engage in a panoramic location quite eccentric keeping other conventional Bahraini assembly points in mind. The purpose of creating this wonderful mirage is Located at the heart of Zallaq, Zallaq Springs is to provide visitors with an organic, natural, serene a destination like no other in Bahrain, offering experience within Bahrain. Zallaq Springs wishes breathtaking indoor and outdoor dining to emulate the soothing resonance, aura and experience, lifestyle therapy, cultural events, overall sense of tranquilly from its inspiration and and exciting new attractions. It has been amalgamate it with a choice of activities and designed for visitors to unwind from their daily cuisines to enhance the customer experience. routines and dissolve themselves by the beauty Zallaq Springs intends on becoming home to and serenity created by an enchanted retreat cultural events and social activities in the Kingdom, within Bahrain. including art and photography exhibitions, festivals and similar occasions aimed at bringing people together to celebrate. It is a destination for families and friends to enjoy together with the range of activities Zallaq Springs offers. 3 4 The project is spread over an area of 25,338 sqm and aims to offer leisure and family oriented activities. It consists of 16 shops, 9 waterfront restaurant/café units, and 1 drive through café unit, and around 168 car parking spaces. Al Zallaq Real Estate wishes to expand its Zallaq Springs is an open meeting point that footprint through an urban development project lies adjacent to a breathtaking residential in the Southern Governorate of the Kingdom of community “The Gardens at Zallaq”. -

Ministry of Works Kingdom of Bahrain

Invitation for Prequalification Feasibility Studies for Bahrain Integrated Transit Lines Ministry of Works Kingdom of Bahrain International Competitive Bidding Expression of Interest (EOI) INVITATION FOR PREQUALIFCATION TENDER NO.: PQ-CED/03/2011 FEASIBILITY STUDIES FOR BAHRAIN INTEGRATED TRANSIT LINES June, 2011 ROADS PLANNING & DESI GN DIRECTORATE Ministry of Works, P O Box No.5 Manama, Kingdom of Bahrain Tel: +973 1754 5666 Fax: +973 17530989 Website: www.works.gov.bh Roads Planning & Design Directorate, Ministry of Works, Kingdom of Bahrain | 1 Invitation for Prequalification Feasibility Studies for Bahrain Integrated Transit Lines Contents 1.0 Introduction ................................................................................................ 4 2.0 Instructions to Consultants ................................................................. 7 3.0 Project Information .............................................................................. 16 4.0 Scope of Services ................................................................................... 24 5.0 Preparation and submission of EoI ............................................... 36 Annexure 1 Format of letter of application ....................................... 38 Annexure 2 ‘Letter of Endorsement’ Format for JV Partners ...... 40 Annexure 3 Project Sheets-Consultant’s Experience .................... 41 Annexure 4 Key Professionals and their CVs ...................................... 42 Annexure 5 Prequalification Questionnaire ....................................... -

Anatomy of a Police State Systematic Repression, Brutality, and Bahrain’S Ministry of Interior Anatomy of a Police State

Anatomy of a Police State Systematic Repression, Brutality, and Bahrain’s Ministry of Interior Anatomy of a Police State Systematic Repression, Brutality, and Bahrain’s Ministry of Interior Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain ©2019, Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain. All rights reserved. Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain (ADHRB) is a non-profit, 501(c)(3) organization based in Washington, D.C. that fosters awareness of and support for democracy and human rights in Bahrain and the Arabian Gulf. Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain (ADHRB) 1001 Connecticut Avenue NW, Suite 205 Washington, D.C. 20036 USA (202) 621-6141 www.adhrb.org Design and layout by Jennifer King Contents Executive Summary .............................................. 5 Methodology .................................................... 8 Introduction ................................................... .10 1 Background: Crime and Criminality in Bahrain .................... 12 2 Command and Control: Structure, Hierarchy, and Organization ..... .16 A. Senior Leadership .................................................... 17 B. Lead Agencies and Directorates ......................................... 22 C. Support Agencies and Directorates ....................................... 32 3 A Policy of Repression: Widespread and Systematic Abuses ....... .38 A. Arbitrary Detention and Warrantless Home Raids ......................... 39 B. Enforced Disappearance ............................................... 42 C. Torture -

Lessons from Lebanon, Bahrain, Syria, and Iraq

C O R P O R A T I O N RESEARCH BRIEF Countering Sectarianism in the Middle East Lessons from Lebanon, Bahrain, Syria, and Iraq Beirut Madinati candidates and delegates cheer while monitoring ballot counts REUTERS/MOHAMED AZAKIR after the close of polling stations during Beirut’s municipal elections in May 2016. ectarianism has become a destructive feature of societies can become more resilient to sectarianism by the modern Middle East. Whether it is driven pursuing a range of actions. by political elites to preserve their regimes, The study, which was funded by the Henry Luce by regional powers to build influence, or by Foundation’s Religion in International Affairs program, religious leaders who are unwilling to accept the arrives at a unique understanding of how communities legitimacy of other faiths, sectarianism is likely inoculate against or recover from sectarianism. Collaborat- Sto remain part of the Middle East’s landscape for years to ing with scholars from different disciplinary backgrounds, come. However, the results of a study by the RAND Cor- RAND researchers explored the experiences of four coun- poration suggest that endless bouts of sectarian violence and tries in the region with mixed sectarian populations and religious conflict are not inevitable and that Middle Eastern histories of sectarian tension or conflict—Lebanon, Bahrain, Key Policies for Countering Sectarianism divided societies in the region is a critical first step in tack- ling the complex challenge of sectarianism. States seeking to counter sectarianism should consider the following national and local measures: • Improve border controls. Cutting off the flow of resources, supplies, and fighters coming from foreign Lebanon sources to fuel sectarian conflict is critical. -

National Study on the Prevalence of Iodine Deficiency Disorders Among School Children Aged 8-12 Years Old in Bahrain

National Study On The Prevalence of Iodine Deficiency Disorders Among School Children Aged 8-12 years old in Bahrain By Dr. Khairya Moosa Head, Nutrition Section Ministry of Health, Bahrain Dr.A.W.M. Abdul Wahab Assistant Undersecretary for Primary Care & Public Health Ministry of Health, Bahrain Dr. Jamal AlSayyad Consultant Epidemiologist Ministry of Health, Bahrain Dr. Bader Z. Hassan Baig Head, Public Health Laboratory Ministry of Health, Bahrain 2000 Table of Contents Subject Page No. Acknowledgements 2 Abstracts 3 Introduction 4 Aim of the study 4 Specific Objectives 5 Subjects & Methods 5 Results 10 Discussion and Recommendations 11 References 24 Appendix 26 1 Acknowledgements This study was partially supported by Joint Ministry of Health and World Health Organization Regional Office (JPRM) fund. The staff of the nutrition section (Ms. Ghada Al-Raees, Mrs. Manal Al- Sairafi and Mrs. Mariam Al-Amer) have cooperated and assisted fully in the field work, data entry and analysis. We are indebted to Dr. Mohammed Rafie, General Surgeon at Salmaniya Medical Complex for his cooperation in conducting neck examination at schools. Sincere thanks to the Ministry of Education officials and school administrators for their support and cooperation. 2 Abstract Background Iodine deficiency disorder (IDD) Continues to be an important public health problem in many countries. In the Eastern Mediterranean Region, 348 million (74% of the population) are considered to be at risk of iodine deficiency. The main objective of this study was to estimate the prevalence of goitre and iodine deficiency among school children in Bahrain. Methods A cross-sectional survey of primary school children was carried out. -

TEL NO FAX NO AREA ADDRESS Al Amal Hospital Multispecialty

GEMS TAZUR BAHRAIN NETWORK- EN CONTACT DETAILS PROVIDER NAME SPECIALITY TEL NO FAX NO AREA ADDRESS HOSPITALS Al Amal Hospital Multispecialty 17602602 17640391 Burri Bldg 1751, Block 754.Boori Hamad town Al Kindi Hospital, Bahrain Multispecialty 17240450 17240043 Al Zenj Bldg 960, Rd 3017, Block 330. AL Rayan Hospital Multispecialty 17495500 77022000 East Riffa Bldg 573, Road 1111, Al Shargi, East Riffa American Mission Hospital Multispecialty 17253447/Ext 2245 17230706 Manama Sh Isa Avenue, Al Gudabiya Block 307. Bahrain Specialist Hospital Clinics Multispecialty 13381338/35157739 13381358 Riffa Bldg 767, Rd 1221, Blck 912 Ibn-Al Nafees Hospital Multispecialty 17823415/17828282 17741606 Al Zenj Bldg 63, Rd 3302, Block 333. MEDICAL CENTER/ POLYCLINIC Al Mosawi Eye Center Ophthalmology 16000002/3/38833190 16000004 Tubli Flat 14, Bldg 69 , Rd 1101, Tubli American Mission Saar Clinic Multispecialty 17790025 17230706 Saar Saar, Opposite Al Mahd School. Bahrain Medical Centre Multispecialty 17000210 17003040 Muharraq Flat28, Bldg 52, Block 204, Ave no 1 Near Oasis, Master Point Muharraq Gulf Air Clinic Multispecialty 17338901 / 17338904 17330466 Muharraq Gulf Air Headquarter, Opposite Bahrain International Airport. International Medical City Co WLL Multispecialty 17490006 17490007 East Riffa Bldg 178, Rd 2702, Block 927, Al-Bayena St, On Riffa Ave Near Lulu H/Market. Kims Bahrain Medical Centre Multispecialty 17822123/17740485 17740610/17 822127 Mahooz Umm-Al-Hassam Ave ,Nr Copperchimney Rest, Rd 3709, Block 335. Middle East Medical Center- Salmabad Multispecialty 17216056 17216209 Salmabad PO Box 80289, 2nd flr Al hayat Medical complex, Next to Ruyan Pharmacy Salmabad Shifa Al Jazeera Medical Centre Multispecialty 17288000/007 17280270 Manama Isa Al Kabeer Avenue, Ras Ruman Block 306. -

Expert Rheumatologist to Join Royal Bahrain

Thursday, September 7, 2017 5 Seef Properties Donates BD5,000 to Muharraq Parents Home Care In line with its ongoing Corporate Social Responsibility efforts, Seef Properties donated BD5,000 to Muharraq Parents Home Care. The cer- emony was attended by the Chairman of Seef Properties, Essa Najibi, Board Members, Fuad Taqi and Eman Al Murbati, as well as Vice Chairman and CSR Committee Chairman of Seef Properties, Dr. Mustafa Al Sayed, and the Chief Executive Officer of Seef Properties, Ahmed Yusuf. The dona- tion was received by the President of Muharraq Parents Home Care, Latifa Al Bursheed. Expert Rheumatologist BBK to to join Royal Bahrain Manama qualification includes Master iving up its commitment and Doctorate Degrees of providing expert and in Rheumatology and excellentL healthcare with a Rehabilitation Medicine from launch range of specialties, Royal Assiut Medical School of Egypt, Bahrain Hospital, will now Sheffield Center for Rheumatic provide services related to Diseases at Sheffield University, diagnosis and treatment of United Kingdom. musculoskeletal diseases Extending a welcome note, and systemic autoimmune Dr. Sheriff Sahadulla, Executive ITM in conditions. Director at RBH, says, “We are Strengthening the existing extremely delighted to welcome team further is a highly Dr. Sahar to RBH. Her rich Chief Executive, qualified and experienced experience adds immense Reyadh Sater Consultant in Rheumatology, depth to our team of doctors Dr. Sahar Saad, Msc, MD, who and we are looking at providing BahrainManama ID can suffice. to be the first to adopt this will be joining RBH from first our patients with the best BK yesterday announced The move, according to innovative technology week of September 2017.