The True Story of Bound by Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JUDAS PRIEST the Broadmoor World Arena Wednesday, June 5, 2019

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE JUDAS PRIEST with special guest Uriah Heep The Broadmoor World Arena Wednesday, June 5, 2019 – 7:30pm Colorado Springs (December 3, 2018) -- AEG Presents and The Broadmoor World Arena are excited to announce JUDAS PRIEST Firepower 2019 Tour with URIAH HEEP at The Broadmoor World Arena on Wednesday, June 5, 2019. With Judas Priest’s latest studio album, Firepower, confirmed as one of the most successful of the band’s entire career - landing in the "Top 5" of 17 countries (including their highest chart placement ever in the U.S., at #5) - demand to see the legendary metal band in concert is higher than ever. Colorado Springs “head-bangers” will get their chance to experience the legendary band when KILO presents Judas Priest Firepower 2019 Tour at The Broadmoor World Arena – one of their 32 tour dates next summer - on Wednesday, June 5 with the classic metal band Uriah Heep. “Metal maniacs - Judas Priest is roaring back to the USA for one more blast of Firepower! Firepower 2019 charges forth with new first-time performances born out of Firepower, as well as fresh classic cuts across the decades from the Priest world metalsphere. Our visual stage set and light show will be scorching a unique, hot, fresh vibe - mixing in headline festivals, as well as the in-your-face venue close ups. We can’t wait to reunite and reignite our maniacs...THE PRIEST IS BACK!” said Judas Priest. Tickets will go on sale Friday, December 7 at 10 a.m., and will range in price from $49.50 to $69.50, plus applicable fees. -

AD GUITAR INSTRUCTION** 943 Songs, 2.8 Days, 5.36 GB

Page 1 of 28 **AD GUITAR INSTRUCTION** 943 songs, 2.8 days, 5.36 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 I Am Loved 3:27 The Golden Rule Above the Golden State 2 Highway to Hell TUNED 3:32 AD Tuned Files and Edits AC/DC 3 Dirty Deeds Tuned 4:16 AD Tuned Files and Edits AC/DC 4 TNT Tuned 3:39 AD Tuned Files and Edits AC/DC 5 Back in Black 4:20 Back in Black AC/DC 6 Back in Black Too Slow 6:40 Back in Black AC/DC 7 Hells Bells 5:16 Back in Black AC/DC 8 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap 4:16 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap AC/DC 9 It's A Long Way To The Top ( If You… 5:15 High Voltage AC/DC 10 Who Made Who 3:27 Who Made Who AC/DC 11 You Shook Me All Night Long 3:32 AC/DC 12 Thunderstruck 4:52 AC/DC 13 TNT 3:38 AC/DC 14 Highway To Hell 3:30 AC/DC 15 For Those About To Rock (We Sal… 5:46 AC/DC 16 Rock n' Roll Ain't Noise Pollution 4:13 AC/DC 17 Blow Me Away in D 3:27 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 18 F.S.O.S. in D 2:41 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 19 Here Comes The Sun Tuned and… 4:48 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 20 Liar in E 3:12 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 21 LifeInTheFastLaneTuned 4:45 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 22 Love Like Winter E 2:48 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 23 Make Damn Sure in E 3:34 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 24 No More Sorrow in D 3:44 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 25 No Reason in E 3:07 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 26 The River in E 3:18 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 27 Dream On 4:27 Aerosmith's Greatest Hits Aerosmith 28 Sweet Emotion -

On Elite Rule of Law and Deterrence

Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs Volume 4 Issue 2 Violence Against Women Symposium and Collected Works September 2016 Caught in the Act but not Punished: on Elite Rule of Law and Deterrence Francesca Jensenius Abby Wood Follow this and additional works at: https://elibrary.law.psu.edu/jlia Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, International and Area Studies Commons, International Law Commons, International Trade Law Commons, Law and Politics Commons, Political Science Commons, Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons, Rule of Law Commons, Social History Commons, and the Transnational Law Commons ISSN: 2168-7951 Recommended Citation Francesca Jensenius and Abby Wood, Caught in the Act but not Punished: on Elite Rule of Law and Deterrence, 4 PENN. ST. J.L. & INT'L AFF. 686 (2016). Available at: https://elibrary.law.psu.edu/jlia/vol4/iss2/13 The Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs is a joint publication of Penn State’s School of Law and School of International Affairs. Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs 2016 VOLUME 4 NO. 2 CAUGHT IN THE ACT BUT NOT PUNISHED: ON ELITE RULE OF LAW AND DETERRENCE Francesca R. Jensenius and Abby K. Wood Most literature on criminal deterrence in law, economics, and criminology assumes that people who are caught for a crime will be punished. The literature focuses on how the size of sanctions and probability of being caught affect criminal behavior. However, in many countries entire groups of people are “above the law” in the sense that they are able to evade punishment even if caught violating the law. -

JUDAS PRIEST BIOGRAPHY There Are Few Heavy Metal Bands That

JUDAS PRIEST BIOGRAPHY There are few heavy metal bands that have managed to scale the heights that Judas Priest have during their nearly 50-year career. Their presence and influence remains at an all-time high as evidenced by 2014's 'Redeemer of Souls' being the highest charting album of their career, a 2010 Grammy Award win for 'Best Metal Performance', being a 2006 VH1 Rock Honors recipient, a 2017 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame nomination, and they will soon release their 18th studio album, 'Firepower', through Epic Records. Judas Priest originally formed in 1969 in Birmingham, England (an area that many feel birthed heavy metal). Rob Halford, Glenn Tipton, K.K. Downing and Ian Hill would be the nucleus of musicians (along with several different drummers over the years) that would go on to change the face of heavy metal. After a 'feeling out' period of a couple of albums, 1974's 'Rocka Rolla' and 1976's 'Sad Wings of Destiny' this line-up truly hit their stride. The result was a quartet of albums that separated Priest from the rest of the hard rock pack - 1977's 'Sin After Sin', 1978's 'Stained Class' and 'Hell Bent for Leather', and 1979's 'Unleashed in the East', which spawned such metal anthems as 'Sinner', 'Diamonds and Rust', 'Hell Bent for Leather', and 'The Green Manalishi (With the Two-Pronged Crown)'. Also, Priest were one of the first metal bands to exclusively wear leather and studs – a look that began during this era and would eventually be embraced by metal heads throughout the world. -

From Epistemic Diversity to Common Knowledge: Rational Rituals and Publicity in Democratic Athens

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics From epistemic diversity to common knowledge: Rational rituals and publicity in democratic Athens. Version 1.0 July 2006 Josiah Ober Stanford Unversity Abstract: Effective organization of knowledge allows democracies to meet Darwinian challenges, and thus avoid elimination by more hierarchical rivals. Institutional processes capable of aggregating diverse knowledge and coordinating action promote the flourishing of democratic communities in competitive environments. Institutions that increase the credibility of commitments and build common knowledge are key aspects of democratic coordination. “Rational rituals,” through which credible commitments and common knowledge are effectively publicized, were prevalent in democratic Athens. Analysis of parts of Lycurgus’ speech Against Leocrates reveals some key features of the how rational rituals worked to build common knowledge in Athens. This paper, adapted from a book-in-progess, is fortthcoming in the journal Episteme. © [email protected] 1 From epistemic diversity to common knowledge: Rational rituals and publicity in democratic Athens. Word count (with notes and bibliography): 9000 By Josiah Ober. [email protected]. (Adapted from Knowledge in Action in Democratic Athens: Innovation, Learning, and Government by the People. A book-in-progress.) In a famous poetic fragment (Fragment 16 West) Sappho sets up a contest among things that might be considered the “most beautiful”: Some say a host of horsemen is the most beautiful thing on the black earth, some say a host of foot-soldiers, some, a fleet of ships; but I say it is whatever one loves. Sappho contrasts her own claim for “the most beautiful” with the answers offered by several imagined groups of others, who may be taken as representing ordinary Greek (male) opinion: each group proposes as its candidate for “the most beautiful” a different form of organized military formation – that is, in each case, a body of men and equipment whose extraordinary beauty inheres in their coordinated movement. -

Antigone Vs Creon Tragic Hero Examining the Traits Listed Below, Find Textual Evidence Throughout the Play That Proves This Character’S Status As a Tragic Hero

Antigone vs Creon Tragic Hero Examining the traits listed below, find textual evidence throughout the play that proves this character’s status as a tragic hero. 1. A person of high estate 2. Suffers because of hamartia 3. Experiences strong emotions and comes to a breaking point 4. Faces a horrible truth (catastrophe) 5. Reversal of fortune (paripateia) 6. The fall and the revelation 3rd Period Antigone 1. A person of high estate “You would think we had suffered enough for the curse of Oedipus”* (Prologue) - Get connection to Oedipus (remember, original audience would know the Oedipus myth) - Princess of Thebes 2. Suffers because of hamartia “Ismene, I am going to bury him…Creon is not strong enough to stand in the way”* - Overconfident, does not think Creon can stop her 3. Experiences strong emotions and comes to a breaking point “Then let me go since all of your words are bitter” (scene iv) - See her fearing death, asking for pity (conflicts with what we saw in scene 2) - Chorus offers her no pity; she did it of her own free will “That must be your excuse I suppose because for me I must bury the brother I love” - Initially wants to bury him out of respect, but now that Ismene refuses to do it, it is a mission for her. Her breaking point because now she is even more determined to break the law. “She had made a noose of her fine linen veil and hanged herself” (exodus) - Her death could also be the breaking point because she committed suicide; she took matters into her own hands; didn’t want to suffer. -

Entertainment Memorabilia Memorabilia Entertainment Entertainment

Entertainment Memorabilia Entertainment I New Bond Street, London I 11 December 2018 I New Bond Street, 24669 Entertainment Memorabilia New Bond Street, London I 11 December 2018 Entertainment Memorabilia New Bond Street, London | Tuesday 11 December 2018 at 12pm BONHAMS ENQUIRIES The following symbol is used to denote that VAT is due on SPECIAL NOTICE TO 101 New Bond Street Katherine Schofield BUYERS London W1S 1SR +44 (0) 20 7393 3871 the hammer price and buyer’s Given the age of some of www.bonhams.com [email protected] premium the Lots they may have been damaged and/or repaired and Claire Tole-Moir † VAT 20% on hammer price VIEWING you should not assume that +44 (0) 20 7393 3984 and buyer’s premium Saturday 8 December a Lot is in good condition. [email protected] 10am to 4pm * VAT on imported items at Electronic or mechanical parts Sunday 9 December may not operate or may not Stephen Maycock a preferential rate of 5% on 10am to 4pm comply with current statutory +44 (0) 20 7393 3844 hammer price and the prevailing Monday 10 December requirements. You should not [email protected] rate on buyer’s premium 9am to 4.30pm assume that electical items Tuesday 11 December Y These lots are subject to designed to operate on mains SALE NUMBER: 9am to 10am CITES regulations, please read electricity will be suitable 24669 the information in the back of the for connection to the mains BIDS catalogue. electricity supply and you should +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 CATALOGUE: obtain a report from a qualified +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax £15 IMPORTANT INFORMATION electrician on their status before doing so. -

Scanned Using Book Scancenter 5131

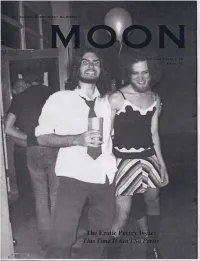

Jonathan Morgan___________________ A Midnight Ride on Paul’s Derriere Listen, my children, and you shall hear Suffice it to say they slunk back to their lair Of that fine tradition all Johnnies revere And Peterson echoed with their cries of despair: A Poetry Contest, in your nomenclature “How now shall we manage, O Divine Mercy, Erotic in name, and though small in stature to express our deep love for all things unseemly? Healthy and bulging with tumescent pride For sodomy, incest, and good Lady Chatterley, And like many bulges, too prominent to hide. For onanists, frotteurists, and bestiality?!? A rude, hairy Tourney of frustrated gripes Freud says that what isn’t expressed will fester! Which yet managed beauty, as Pan from his pipes. What we hold in now will be worse next semester! A contest that Johnnies created, in trust. And though we are craven and burning with lust, As a repository for their various lusts. Most average Johnnies are homier than us!” On one fine spring morning, in 2004, The editors anguished long into the night. The Dean paid a call on the Moon editors. But had they a plan, by first morning light. He asked them, with feigned nonchalance, to accompany Although it would gall them, they must take a chance, Him back to his office, and they complied readily. A crash-course in administrative song-and-dance: Then, barring his door tightly behind their backs They’d barter, cajole, beseech, threaten and stall. And tuning upon them, as if to attack, said And try to appease the Gods of Weigle Hall. -

Vinyl Catalogue 2014

VINYL CATALOGUE 2014 Established in 2004, Back On Black - together with subsidiary label Back On Black Rock Classics - specialises in vinyl editions of classic metal and rock albums and is dedicated to providing top quality releases for record collectors and rock fans worldwide. Our releases are pressed on exquisite, heavyweight vinyl to produce the very best in sound quality with a mesmerizing tactile feel that makes them a pleasure to handle. Beautiful vinyl colours are carefully chosen to complement the artwork, with some releases available in a variety of colours for the dedicated collector. Many releases are double, or even triple, LPs! The artwork itself is re-worked to faithfully interpret the original album, and reproduced on superior grade gatefold sleeves in heavyweight card with a superb and un-rivalled finish. As well as all our re-mastered LPs of classic albums from throughout history, Back On Black also issues many exclusive vinyl editions of contemporary metal and rock releases. Far from being dead, our beloved vinyl format is going from strength to strength – and Back On Black is proud to serve the needs of the vinyl connoisseur! Just take a look at our catalogue of releases to see the calibre of albums we release! Combine your favourite rock and metal with your favourite format – and get your music Back On Black! CONtact: PHONE: +44 (0)1491 825029 MAILORDER: PLASTICHEAD.COM UK SALES: [email protected] INTERNATIONAL SALES: [email protected] BACKONBLACK.COM facebook.COM/BACKONBLACKRECORDS PLASTICHEAD.COM All titles subject to availability due to territorial or licensing terms. -

Judas Priest Corregida

EL NOMBRE 1975 1980 British Steel 1984 1992 2008 Toda Europa los ve pasar con su primera El mánager Bill Kurbishley y Allom otra vez Halford anuncia su debut en solitario con Aparece el disco experimental Uno de los integrantes, revisando sus discos, gran gira. Inglaterra será el sitio de como productor dan lugar al Defenders Fight. Luego de tres meses se lleva Nostradamus. se topa con uno de Bob Dylan llamado John partida y llegada: Lateld (Man Hall, el of the Faith de la formación Halford, consigo a Travis. Lo acompañan también 2008 Nostradamus Wesley Harding, el cual contiene el tema 21 de febrero) y Coventri Tech (el 12 de Tipton, Downing, Hill y Holland. Brian Tilse y Russ Parish a las guitarras, y "The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest", diciembre). Brillan temas como “Freewheel Burning”, Jay Jay al bajo. por lo que propuso el nombre Judas Priest; Hinch deja los tambores luego de una “Jawbreaker”, “The Sentinel”, “Some así surgió el nombre de la banda. presentación memorable en el Reading Heads Are Gonna Roll” o “Rock Hard Ride En noviembre, el “Metal God” sustituye, Festival. Alan Skip Moore regresa a la Free”, este último es un remake del sin abandonar su nuevo proyecto, a banda y vuelven a componer junto a setentero “Fight for your Life”. Ronnie James Dio en Black Sabbath. Priest. Quienes aún permanecían en Judas 1985 1999 En diciembre los estudios London’s (K. K., Glen e Ian) anuncian su separación. Priest... Live Rob Halford se declara homosexual en Morgan reciben al cuarteto para la televisión y de eso surge la banda Two. -

Halford, Rob (B

Halford, Rob (b. 1951) by Krista L. May Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2008 glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Rob Halford performing with Judas Priest in With a four-and-a-half octave vocal range, Rob Halford--dubbed "The Metal God" by Moline, Illinois in 2005. fans and critics--is one of the most talented vocalists in heavy metal music. Though Photograph by Zach Petersen. many of his friends, family members, and fellow musicians have known for quite some This image appears time that he is gay, he did not come out publicly until 1998 in an interview that aired under the Creative on MTV. Commons Attribution ShareAlike 2.0 license. Shortly after proclaiming his sexual identity in that interview, Halford was profiled in The Advocate, where he spoke openly about his sexuality and his decision to come out in the media. Halford had met and performed with the queercore band Pansy Division--who encouraged him to come out-- at several gay pride events in 1997. Even though he had support from some friends and fellow musicians, coming out publicly was especially difficult because of the small number of gay metal artists who are out. Additionally, as a recovering alcoholic, Halford did not feel like he was in a place where he could come out publicly until he was more secure in himself. In The Advocate, Halford described a volatile relationship with a lover that was fueled by drugs and alcohol. After a particularly violent fight, he realized he needed to leave for his own safety. -

FRIDAY, JUNE 28Th at 8:00 PM CITIZENS BUSINESS BANK ARENA

JUDAS PRIEST ADDS SECOND SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA DATE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: With Judas Priest’s latest studio album, Firepower, confirmed as one of the most successful of the band’s entire career - landing in the "top 5" of 17 countries (including their highest chart placement ever in the U.S., at #5) - demand to see the legendary metal band in concert is higher than ever. And North American headbangers will get their chance to experience the legendary band on a nearby concert stage this coming spring/summer, when Priest will tour throughout the continent - with the classic metal band Uriah Heep as support. The tour added a second stop in Southern California at Citizens Business Bank Arena on Friday, June 28, 2019. Tickets go on sale Friday, March 29 at 10am at ticketmaster.com. “Metal maniacs - Judas Priest is roaring back to the USA for one more blast of Firepower! Firepower 2019 charges forth with new first time performances born out of Firepower, as well as fresh classic cuts across the decades from the Priest world metalsphere. Our visual stage set and light show will be scorching a unique, hot, fresh vibe - mixing in headline festivals, as well as the in-your-face venue close ups. We can’t wait to reunite and reignite our maniacs...THE PRIEST IS BACK!” -Judas Priest There are few heavy metal bands that have managed to scale the heights that Judas Priest have during their nearly 50-year career - responsible for issuing such all-time classic albums as British Steel, Screaming for Vengeance, and Painkiller, as well as the anthems “Breaking the Law,” “Living After Midnight,” and “You’ve Got Another Thing Coming.” And Priest’s presence and influence remains strong, as evidenced by the chart performance of 'Firepower' and its glowing reviews, a Grammy Award win for 'Best Metal Performance', plus being a VH1 Rock Honors recipient and a Rock and Roll Hall of Fame nomination.