From Epistemic Diversity to Common Knowledge: Rational Rituals and Publicity in Democratic Athens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Athens' Domain

Athens’ Domain: The Loss of Naval Supremacy and an Empire Keegan Laycock Acknowledgements This paper has a lot to owe to the support of Dr. John Walsh. Without his encouragement, guid- ance, and urging to come on a theoretically educational trip to Greece, this paper would be vastly diminished in quality, and perhaps even in existence. I am grateful for the opportunity I have had to present it and the insight I have gained from the process. Special thanks to the editors and or- ganizers of Canta/ἄειδε for their own patience and persistence. %1 For the Athenians, the sea has been a key component of culture, economics, and especial- ly warfare. The Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC) displayed how control of the waves was vital for victory. This was not wholly apparent at the start of the conflict. The Peloponnesian League was militarily led by Sparta who was the greatest land power in Greece; to them naval warfare was excessive. Athens, as the head of the Delian League, was the greatest sea power in Greece whose strengths lay in their navy. However, through a combination of factors, Athens lost control of the sea and lost the war despite being the superior naval power at the war’s outset. Ultimately, Athens lost because they were unable to maintain strong naval authority. The geographic position of Athens and many of its key resources ensured land-based threats made them vulnerable de- spite their naval advantage. Athens also failed to exploit their naval supremacy as they focused on land-based wars in Sicily while the Peloponnesian League built up a rivaling navy of its own. -

Download the Greek Wars: the Failure of Persia, George Cawkwell

The Greek Wars: The Failure of Persia, George Cawkwell, Oxford University Press, 2006, 0199299838, 9780199299836, 316 pages. The Greek Wars treats the whole course of Persian relations with the Greeks from the coming of Cyrus in the 540s down to Alexander the Great's defeat of Darius III in 331 BC. Cawkwell discusses from a Persian perspective major questions such as why Xerxes' invasion of Greece failed, and how important a part the Great King played in Greek affairs in the fourth century. Cawkwell's views are at many points original: in particular, his explanation of how and why the Persian invasion of Greece failed challenges the prevailing orthodoxy, as does his view of the importance of Persia in Greek affairs for the two decades after the King's Peace. Persia, he concludes, was destroyed by Macedonian military might but moral decline had no part in it; the Macedonians who had subjected Greece were too good an army, but their victory was not easy.. DOWNLOAD HERE The Greeks and the Persians from the sixth to the fourth centuries, Hermann Bengtson, 1968, History, 478 pages. The Fall of the Athenian Empire , Donald Kagan, 1991, History, 455 pages. An overview of history in ancient Athens, beginning with the ill-fated Sicilian expedition of 413 B.C. and ends with the surrender of Athens to Sparta in 404 B.C.. A History of Greece From the Earliest Times to the Roman Conquest : with Supplementary Chapters on the History of Literature and Art, Sir William Smith, George Washington Greene, 1863, , 704 pages. Alexander the Great selected texts from Arrian, Curtius and Plutarch, Tania Gergel, Michael Wood, Sep 28, 2004, , 150 pages. -

JUDAS PRIEST the Broadmoor World Arena Wednesday, June 5, 2019

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE JUDAS PRIEST with special guest Uriah Heep The Broadmoor World Arena Wednesday, June 5, 2019 – 7:30pm Colorado Springs (December 3, 2018) -- AEG Presents and The Broadmoor World Arena are excited to announce JUDAS PRIEST Firepower 2019 Tour with URIAH HEEP at The Broadmoor World Arena on Wednesday, June 5, 2019. With Judas Priest’s latest studio album, Firepower, confirmed as one of the most successful of the band’s entire career - landing in the "Top 5" of 17 countries (including their highest chart placement ever in the U.S., at #5) - demand to see the legendary metal band in concert is higher than ever. Colorado Springs “head-bangers” will get their chance to experience the legendary band when KILO presents Judas Priest Firepower 2019 Tour at The Broadmoor World Arena – one of their 32 tour dates next summer - on Wednesday, June 5 with the classic metal band Uriah Heep. “Metal maniacs - Judas Priest is roaring back to the USA for one more blast of Firepower! Firepower 2019 charges forth with new first-time performances born out of Firepower, as well as fresh classic cuts across the decades from the Priest world metalsphere. Our visual stage set and light show will be scorching a unique, hot, fresh vibe - mixing in headline festivals, as well as the in-your-face venue close ups. We can’t wait to reunite and reignite our maniacs...THE PRIEST IS BACK!” said Judas Priest. Tickets will go on sale Friday, December 7 at 10 a.m., and will range in price from $49.50 to $69.50, plus applicable fees. -

AD GUITAR INSTRUCTION** 943 Songs, 2.8 Days, 5.36 GB

Page 1 of 28 **AD GUITAR INSTRUCTION** 943 songs, 2.8 days, 5.36 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 I Am Loved 3:27 The Golden Rule Above the Golden State 2 Highway to Hell TUNED 3:32 AD Tuned Files and Edits AC/DC 3 Dirty Deeds Tuned 4:16 AD Tuned Files and Edits AC/DC 4 TNT Tuned 3:39 AD Tuned Files and Edits AC/DC 5 Back in Black 4:20 Back in Black AC/DC 6 Back in Black Too Slow 6:40 Back in Black AC/DC 7 Hells Bells 5:16 Back in Black AC/DC 8 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap 4:16 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap AC/DC 9 It's A Long Way To The Top ( If You… 5:15 High Voltage AC/DC 10 Who Made Who 3:27 Who Made Who AC/DC 11 You Shook Me All Night Long 3:32 AC/DC 12 Thunderstruck 4:52 AC/DC 13 TNT 3:38 AC/DC 14 Highway To Hell 3:30 AC/DC 15 For Those About To Rock (We Sal… 5:46 AC/DC 16 Rock n' Roll Ain't Noise Pollution 4:13 AC/DC 17 Blow Me Away in D 3:27 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 18 F.S.O.S. in D 2:41 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 19 Here Comes The Sun Tuned and… 4:48 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 20 Liar in E 3:12 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 21 LifeInTheFastLaneTuned 4:45 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 22 Love Like Winter E 2:48 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 23 Make Damn Sure in E 3:34 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 24 No More Sorrow in D 3:44 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 25 No Reason in E 3:07 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 26 The River in E 3:18 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 27 Dream On 4:27 Aerosmith's Greatest Hits Aerosmith 28 Sweet Emotion -

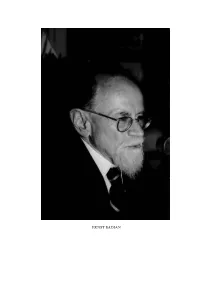

ERNST BADIAN Ernst Badian 1925–2011

ERNST BADIAN Ernst Badian 1925–2011 THE ANCIENT HISTORIAN ERNST BADIAN was born in Vienna on 8 August 1925 to Josef Badian, a bank employee, and Salka née Horinger, and he died after a fall at his home in Quincy, Massachusetts, on 1 February 2011. He was an only child. The family was Jewish but not Zionist, and not strongly religious. Ernst became more observant in his later years, and received a Jewish funeral. He witnessed his father being maltreated by Nazis on the occasion of the Reichskristallnacht in November 1938; Josef was imprisoned for a time at Dachau. Later, so it appears, two of Ernst’s grandparents perished in the Holocaust, a fact that almost no professional colleague, I believe, ever heard of from Badian himself. Thanks in part, however, to the help of the young Karl Popper, who had moved to New Zealand from Vienna in 1937, Josef Badian and his family had by then migrated to New Zealand too, leaving through Genoa in April 1939.1 This was the first of Ernst’s two great strokes of good fortune. His Viennese schooling evidently served Badian very well. In spite of knowing little English at first, he so much excelled at Christchurch Boys’ High School that he earned a scholarship to Canterbury University College at the age of fifteen. There he took a BA in Classics (1944) and MAs in French and Latin (1945, 1946). After a year’s teaching at Victoria University in Wellington he moved to Oxford (University College), where 1 K. R. Popper, Unended Quest: an Intellectual Autobiography (La Salle, IL, 1976), p. -

A View from the City

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OXFORD ISSUE 3 SUMMER 2015 A VIEW FROM THE CITY LEIGH INNES (1994) AND LIFE IN THE MARKETPLACE ALSO IN THIS ISSUE GEORGE CAWKWELL CELEBRATES 65 YEARS AT UNIV LOUISE TAYLOR (2011) ON THE PURSUIT OF PERFECTION ELECTION NIGHT SPECIAL WITH SIR IVOR CREWE THE MAGNA CARTA AT UNIV JOHN RADCLIFFE’S MEDICAL LEGACY FROM THE EDITOR University College Oxford OX1 4BH elcome to the Summer 2015 issue of The Martlet, the magazine for www.univ.ox.ac.uk Members and Friends of University College Oxford. I would like to Wexpress my sincere thanks to those Old Members, students, Fellows, staff www.facebook.com/univalumni and Friends of the College who contributed to this issue. [email protected] I would also like to take this opportunity to thank our extended Univ team – © University College, Oxford, 2015 Charles New and Andrew Boyle at B&M Design & Advertising Limited, who produce the magazine; Clare Holt and the team at Nice Tree Films who worked tirelessly on Produced by B&M Design & Advertising our recent videos – in particular the Election Night Special, for which they stayed www.bm-group.co.uk up well past their bedtimes! Michelle Enoch and the team at h2o creative for their splendid design concepts for the 1249 Society, and our unofficial ‘in-house’ designer Rob Moss and photographer Rachel Harrison for all their hard work on our event If you would like to share your thoughts or programmes and College photography. comments about The Martlet, please e-mail: [email protected] Enormous thanks also to Dr Robin Darwall-Smith and Frances Lawrence for their invaluable help with the In Memoriam section of the magazine. -

Michael Attyah Flower

1 MICHAEL ATTYAH FLOWER Address Department of Classics Princeton University 141 East Pyne Princeton, NJ 08544 email: [email protected] Special Interests: Greek History and Historiography, Greek Religion, Ancient Sparta, Achaemenid Persia Education Ph.D., May 1986, in Classics, Brown University. B.A., M.A., 1981, in Classics, University College, Oxford University. (with concentration in ancient history and philosophy) B.A., 1978, in Classics, University of California, Berkeley. Summer Session, American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1977. Employment 2018—: David Magie '97 Class of 1897 Professor of Classics 2015—: Professor of Classics, Princeton University. 2013—2015: Senior Research Scholar, with continuing appointment, and Lecturer with the Rank of Professor, Princeton University. 2007—2012: Senior Research Scholar, with continuing appointment, Princeton University. 2003—2007: Lecturer in Classics, Princeton University. Spring 2002: Visiting Professor of Classics, Princeton University. Spring 1998: Visiting Associate Professor of Greek, Bryn Mawr College. 1987—2003: Assistant to Associate to John W. Wetzel Professor of Classics, Franklin and Marshall College. Chair of the Department in 2000/1 and 2002/3. 2 Awards Old Dominion Research Professor, Humanities Council, Princeton University, 2018/19 Loeb Classical Library Foundation Fellowship, Fall 2010. NEH Fellowship for College Teachers and Independent Scholars, 1999/2000. Visiting Scholar, Wolfson College, Oxford University, 1993/4. Junior Fellow, The Center for Hellenic Studies, Washington D.C., 1990/1. National Endowment for the Humanities Summer Stipend, 1990. Michaelides Fellowship, Brown University, Spring 1985. University Fellowship, Brown University, 1981/2. Dr. F. Parkes Weber Prize for 1975, Royal Numismatic Society London, for an essay entitled, “Alexander of Epirus, Alexander of Macedonia, and the Gold Coinage of Tarentum.” Professional Service Member of the Planning Committee: Fate and Prognostication in Early China and the Ancient Mediterranean. -

Interstate Alliances of the Fourth-Century BCE Greek World: a Socio-Cultural Perspective

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2016 Interstate Alliances of the Fourth-Century BCE Greek World: A Socio-Cultural Perspective Nicholas D. Cross The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1479 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] INTERSTATE ALLIANCES IN THE FOURTH-CENTURY BCE GREEK WORLD: A SOCIO-CULTURAL PERSPECTIVE by Nicholas D. Cross A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 Nicholas D. Cross All Rights Reserved ii Interstate Alliances in the Fourth-Century BCE Greek World: A Socio-Cultural Perspective by Nicholas D. Cross This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________ __________________________________________ Date Jennifer Roberts Chair of Examining Committee ______________ __________________________________________ Date Helena Rosenblatt Executive Officer Supervisory Committee Joel Allen Liv Yarrow THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Interstate Alliances of the Fourth-Century BCE Greek World: A Socio-Cultural Perspective by Nicholas D. Cross Adviser: Professor Jennifer Roberts This dissertation offers a reassessment of interstate alliances (συµµαχία) in the fourth-century BCE Greek world from a socio-cultural perspective. -

On Elite Rule of Law and Deterrence

Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs Volume 4 Issue 2 Violence Against Women Symposium and Collected Works September 2016 Caught in the Act but not Punished: on Elite Rule of Law and Deterrence Francesca Jensenius Abby Wood Follow this and additional works at: https://elibrary.law.psu.edu/jlia Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, International and Area Studies Commons, International Law Commons, International Trade Law Commons, Law and Politics Commons, Political Science Commons, Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons, Rule of Law Commons, Social History Commons, and the Transnational Law Commons ISSN: 2168-7951 Recommended Citation Francesca Jensenius and Abby Wood, Caught in the Act but not Punished: on Elite Rule of Law and Deterrence, 4 PENN. ST. J.L. & INT'L AFF. 686 (2016). Available at: https://elibrary.law.psu.edu/jlia/vol4/iss2/13 The Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs is a joint publication of Penn State’s School of Law and School of International Affairs. Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs 2016 VOLUME 4 NO. 2 CAUGHT IN THE ACT BUT NOT PUNISHED: ON ELITE RULE OF LAW AND DETERRENCE Francesca R. Jensenius and Abby K. Wood Most literature on criminal deterrence in law, economics, and criminology assumes that people who are caught for a crime will be punished. The literature focuses on how the size of sanctions and probability of being caught affect criminal behavior. However, in many countries entire groups of people are “above the law” in the sense that they are able to evade punishment even if caught violating the law. -

JUDAS PRIEST BIOGRAPHY There Are Few Heavy Metal Bands That

JUDAS PRIEST BIOGRAPHY There are few heavy metal bands that have managed to scale the heights that Judas Priest have during their nearly 50-year career. Their presence and influence remains at an all-time high as evidenced by 2014's 'Redeemer of Souls' being the highest charting album of their career, a 2010 Grammy Award win for 'Best Metal Performance', being a 2006 VH1 Rock Honors recipient, a 2017 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame nomination, and they will soon release their 18th studio album, 'Firepower', through Epic Records. Judas Priest originally formed in 1969 in Birmingham, England (an area that many feel birthed heavy metal). Rob Halford, Glenn Tipton, K.K. Downing and Ian Hill would be the nucleus of musicians (along with several different drummers over the years) that would go on to change the face of heavy metal. After a 'feeling out' period of a couple of albums, 1974's 'Rocka Rolla' and 1976's 'Sad Wings of Destiny' this line-up truly hit their stride. The result was a quartet of albums that separated Priest from the rest of the hard rock pack - 1977's 'Sin After Sin', 1978's 'Stained Class' and 'Hell Bent for Leather', and 1979's 'Unleashed in the East', which spawned such metal anthems as 'Sinner', 'Diamonds and Rust', 'Hell Bent for Leather', and 'The Green Manalishi (With the Two-Pronged Crown)'. Also, Priest were one of the first metal bands to exclusively wear leather and studs – a look that began during this era and would eventually be embraced by metal heads throughout the world. -

On the Daimonion of Socrates

SAPERE Scripta Antiquitatis Posterioris ad Ethicam REligionemque pertinentia Schriften der späteren Antike zu ethischen und religiösen Fragen Herausgegeben von Heinz-Günther Nesselrath, Reinhard Feldmeier und Rainer Hirsch-Luipold Band XVI Plutarch On the daimonion of Socrates Human liberation, divine guidance and philosophy edited by Heinz-Günther Nesselrath Introduction, Text, Translation and Interpretative Essays by Donald Russell, George Cawkwell, Werner Deuse, John Dillon, Heinz-Günther Nesselrath, Robert Parker, Christopher Pelling, Stephan Schröder Mohr Siebeck e-ISBN PDF 978-3-16-156444-4 ISBN 978-3-16-150138-8 (cloth) ISBN 987-3-16-150137-1 (paperback) The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Natio- nal bibliographie; detailed bibliographic data is availableon the Internet at http:// dnb.d-nb.de. © 2010 by Mohr Siebeck Tübingen. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher’s written permission. This applies particularly to reproductions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. This book was typeset by Christoph Alexander Martsch, Serena Pirrotta and Thorsten Stolper at the SAPERE Research Institute, Göttingen, printed by Gulde- Druck in Tübingen on non-aging paper and bound by Buchbinderei Spinner in Ottersweier. Printed in Germany. SAPERE Greek and Latin texts of Later Antiquity (1st–4th centuries AD) have for a long time been overshadowed by those dating back to so-called ‘classi- cal’ times. The first four centuries of our era have, however, produced a cornucopia of works in Greek and Latin dealing with questions of philoso- phy, ethics, and religion that continue to be relevant even today. -

Illinois Classical Studies

— 11 Philip II, The Greeks, and The King 346-336 B.C. JOHN BUCKLER "Gentlemen may cry, Peace, Peace! but there is no peace." Patrick Henry The aim of this piece is to examine a congeries of diplomatic, political, and legal arrangements and obligations that linked the Greeks, Macedonians, and Persians in various complicated ways during Philip's final years. The ties among them all were then often tangled and now imperfectly understood and incompletely documented. These matters evoke such concepts as the King's Peace and the Common Peace, and involve a number of treaties, some bilateral between Philip and individual states, others broader, as with the Peace of Philokrates between himself and his allies and the Athenians and theirs, and finally the nature of Philip's settlement with the Greeks in 338/7. In the background there always stood the King, who never formally renounced the rights that he enjoyed under the King's Peace of 386, even though he could seldom directly enforce them. It is an irony of history that Philip used the concept of a common peace in Greece both to exclude the King from Greek affairs and also as a tool of war against him. By so doing, Philip rejected the very basis of the King's Peace as it was originally drafted and later implemented. In its place he resurrected the memory of the days when the Greeks had thwarted Xerxes' invasion, and fanned the desire for retaliation of past wrongs, a theme that Alexander would also later put to good use.' The original version of this paper was presented at the annual meeting of the Association of Ancient Historians in Los Angeles on 4 May 1990.