Vedalak¶Aƒa Texts: Search and Analysis Sam∂K¶Ikå Series No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

APA Newsletter on Asian and Asian-American Philosophers And

NEWSLETTER | The American Philosophical Association Asian and Asian-American Philosophers and Philosophies FALL 2018 VOLUME 18 | NUMBER 1 Prasanta Bandyopadhyay and R. Venkata FROM THE EDITOR Raghavan Prasanta S. Bandyopadhyay Some Critical Remarks on Kisor SUBMISSION GUIDELINES AND Chakrabarti’s Idea of “Observational INFORMATION Credibility” and Its Role in Solving the Problem of Induction BUDDHISM Kisor K. Chakrabarti Madhumita Chattopadhyay Some Thoughts on the Problem of Locating Early Buddhist Logic in Pāli Induction Literature PHILOSOPHY OF LANGUAGE Rafal Stepien AND GRAMMAR Do Good Philosophers Argue? A Buddhist Approach to Philosophy and Philosophy Sanjit Chakraborty Prizes Remnants of Words in Indian Grammar ONTOLOGY, LOGIC, AND APA PANEL ON DIVERSITY EPISTEMOLOGY Ethan Mills Pradeep P. Gokhale Report on an APA Panel: Diversity in Īśvaravāda: A Critique Philosophy Palash Sarkar BOOK REVIEW Cārvākism Redivivus Minds without Fear: Philosophy in the Indian Renaissance Reviewed by Brian A. Hatcher VOLUME 18 | NUMBER 1 FALL 2018 © 2018 BY THE AMERICAN PHILOSOPHICAL ASSOCIATION ISSN 2155-9708 APA NEWSLETTER ON Asian and Asian-American Philosophy and Philosophers PRASANTA BANDYOPADHYAY, EDITOR VOLUME 18 | NUMBER 1 | FALL 2018 opponent equally. He pleads for the need for this sort of FROM THE EDITOR role of humanism to be incorporated into Western analytic philosophy. This incorporation, he contends, has a far- Prasanta S. Bandyopadhyay reaching impact on both private and public lives of human MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY beings where the love of wisdom should go together with care and love for fellow human beings. The fall 2018 issue of the newsletter is animated by the goal of reaching a wider audience. Papers deal with issues SECTION 2: ONTOLOGY, LOGIC, AND mostly from classical Indian philosophy, with the exception EPISTEMOLOGY of a report on the 2018 APA Eastern Division meeting panel on “Diversity in Philosophy” and a review of a book about This is the longest part of this issue. -

Yoga and the Jesus Prayerâ•Fla Comparison Between Aá¹

Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies Volume 28 Article 7 2015 Yoga and the Jesus Prayer—A Comparison between aṣtānga yoga in the Yoga Sūtras of Patañjali and the Psycho-Physical Method of Hesychasm Eiji Hisamatsu Ryukoku University Ramesh Pattni Oxford University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.butler.edu/jhcs Recommended Citation Hisamatsu, Eiji and Pattni, Ramesh (2015) "Yoga and the Jesus Prayer—A Comparison between aṣtānga yoga in the Yoga Sūtras of Patañjali and the Psycho-Physical Method of Hesychasm," Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies: Vol. 28, Article 7. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.7825/2164-6279.1606 The Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies is a publication of the Society for Hindu-Christian Studies. The digital version is made available by Digital Commons @ Butler University. For questions about the Journal or the Society, please contact [email protected]. For more information about Digital Commons @ Butler University, please contact [email protected]. Hisamatsu and Pattni: Yoga and the Jesus Prayer—A Comparison between a?t?nga yoga in th Yoga and the Jesus Prayer—A Comparison between aṣtānga yoga in the Yoga Sūtras of Patañjali and the Psycho-Physical Method of Hesychasm Eiji Hisamatsu Ryukoku University and Ramesh Pattni Oxford University INTRODUCTION the “Jesus Prayer” in the late Byzantine era and The present article will try to show differences “yoga” in ancient India. A prayer made much and similarities in description about the ascetic use of by Christians in the Eastern Orthodox teaching and mystical experience of two totally Church is the so-called “Jesus Prayer” or different spiritual traditions, i.e. -

Practice of Karma Yoga

PRACTICE OF KARMA YOGA By SRI SWAMI SIVANANDA SERVE, LOVE, GIVE, PURIFY, MEDITATE, REALIZE Sri Swami Sivananda So Says Founder of Sri Swami Sivananda The Divine Life Society A DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY PUBLICATION Sixth Edition: 1995 (4,000 Copies) World Wide Web (WWW) Edition: 2001 WWW site: http://www.SivanandaDlshq.org/ This WWW reprint is for free distribution © The Divine Life Trust Society ISBN 81-7052-014-2 Published By THE DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY P.O. SHIVANANDANAGAR—249 192 Distt. Tehri-Garhwal, Uttaranchal, Himalayas, India. OM Dedicated to all selfless, motiveless, disinterested workers of the world who are struggling hard to get knowledge of the Self by purifying their minds, by getting Chitta Suddhi through Nishkama Karma Yoga OM PUBLISHERS’ NOTE The nectar-like teachings of His Holiness Sri Swami Sivananda Saraswati, the incomparable saint of the Himalayas, famous in song and legend, are too well-known to the intelligent public as well as to the earnest aspirant of knowledge Divine. Their aim and object is nothing but emancipation from the wheel of births and deaths through absorption of the Jiva with the supreme Soul. Now, this emancipation can be had only through right knowledge. It is an undisputed fact that it is almost a Herculean task for the man in the street, blinded as he is by worldly desires of diverse kinds, to forge his way to realisation of God. Not only is it his short-sightedness that stands in the way but innumerable other difficulties and obstacles hamper the progress onward towards the goal. He is utterly helpless until someone who has successfully trodden the path, comes to his aid or rescue, takes him by the hand, leads him safely through the inextricable traps and pitfalls of worldly temptation and desires, and finally brings him to his destination which is the crowning glory of the be-all and end-all of life, where all suffering ceases and all quest comes to an end. -

Against a Hindu God

against a hindu god Against a Hindu God buddhist philosophy of religion in india Parimal G. Patil columbia university press——new york columbia university press Publishers Since 1893 new york chichester, west sussex Copyright © 2009 Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Patil, Parimal G. Against a Hindu god : Buddhist philosophy of religion in India / Parimal G. Patil. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-231-14222-9 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-231-51307-4 (ebook) 1. Knowledge, Theory of (Buddhism) 2. God (Hinduism) 3. Ratnakirti. 4. Nyaya. 5. Religion—Philosophy. I. Title. BQ4440.P38 2009 210—dc22 2008047445 ∞ Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. Printed in the United States of America c 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 References to Internet Web sites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared. For A, B, and M, and all those who have called Konark home contents abbreviations–ix Introduction–1 1. Comparative Philosophy of Religions–3 1. Disciplinary Challenges–5 2. A Grammar for Comparison–8 3. Comparative Philosophy of Religions–21 4. Content, Structure, and Arguments–24 Part 1. Epistemology–29 2. Religious Epistemology in Classical India: In Defense of a Hindu God–31 1. Interpreting Nyaya Epistemology–35 2. The Nyaya Argument for the Existence of Irvara–56 3. Defending the Nyaya Argument–69 4. -

30. Prayatna Stabakam

Sincere Thanks To: 1. SrI Srinivasan Narayanan swami for providing Sanskrit text and proof reading the document 2. Sau R Chitralekha, Nedumtheru SrI Mukund Srinivasan, SrI Srivallabhan, SrI Srivatsan, SrI Lakshminarasimhan Sridhar, www.exoticindiaart.com, SrI Shreekrishna Akilesh and SrI V Ramaswamy for pictures and artwork. 3. Smt Jayashree Muralidharan for eBook assembly CONTENTS Introductory Note to yatna stabakam 1 by Sri. V. Sadagopan Slokams and Commentaries 5 Slokam 1-10 7-20 Slokam 11-20 21-32 Slokam 21-30 31-45 Slokam 31-39 46-57 . ïI>. ïI pÒavit smet ïIinvas präü[e nm>. ïImte ramanujay nm>. ïImte ingmaNt mhadeizkay nm>. ïI ve»qaXvir Svaimne nm>. lúmIshöm! (ïIve»qaXvirk«tm!) lakshmI sahasram Stbk> 6 àyÆ (yÆ) Stbk> stabakam 6 prayatna (yatna) stabakam INTRODUCTION BY SRI. V. SADAGOPAN: This stabakam is entitled Yatna (Prayatna) stabakam. Yatnam means an effort, an endeavour to accomplish some thing. We have to strive, if we have some desired goals. Things won’t fall in one's lap without any Yatnam/Prayatnam. If the desired fruit is not achieved, there is no dosham (blemish): “yatna krte na sidhyati ko atra dosha:?”. One has to persevere however with diligence on what one has deliberately chosen. Yatnam also means effort like the word yatanam. Both words are derived from the root “yat” meaning to attempt or to endeavour. The words of wisdom taught to us are: All with a big family should strive to assemble wealth, when they are at an age enjoying perfect health (sarva: kalye vayasi yatate labdum arthAn kuDumbhI). This reminds us of VarAha carama Slokam, when the Lord advises us to think of Him, when one's body is strong and mind is clear instead of waiting for the time, when one is unconscious like a log or 1 stone during the last moments of one's life. -

Tenets of Vaisheshika Philosophy in Ayurveda

Published online in http://ijam.co.in ISSN: 0976-5921 International Journal of Ayurvedic Medicine, 2013, 4(4), 245-251 Tenets of Vaisheshika philosophy in Ayurveda Review article Archana I1*, Praveen Kumar A2, Mahesh Vyas3 1. Ph.D Scholar, Dept of Basic Principles, 2. Ph.D Scholar, Dept of Dravya Guna, 3. Associate professor, Dept of Basic Principles, I.P.G.T. & R. A., Gujarat Ayurveda University, Jamnagar Abstract Ayurveda is the ancient science of life, which is developed by integrating various other systems of knowledge like philosophy, arts, literature and so on. In this regard the verse “Sarva Parishadamidam Shastram” told by Chakrapani, the commentator of Charaka Samhita, a great lexicon of Ayurveda much suits here. Even though Ayurveda is an applied science it incorporates the philosophical principles which are so modified that these principles have become Ayurvedic in nature and considered as Ayurvedic principles. Among the six orthodox schools of philosophy, Vaishishika system is also one and Ayurveda has taken the fundamental principles of this school of thought which are helpful in its applied aspects. Key words: Philosophy, Vaisheshika, Ayurveda, Padartha (Category), Health Introduction: the 25 elements (2), Vaisheshika consider The scope of philosophy is 6 Padarthas/categories (3) and so on. The extensive and wide spread. It includes all central premise of these Darshana is to the efforts to accomplish the total understand creation in total with the help knowledge i.e. the beginning, development of the Tatvas/elements and thereby getting and destruction of the universe. The eradication from all type of miseries (4). discussion of the same is the main subject Vedas are the root source of all the matter in all the branches of philosophy. -

Talks with Ramana Maharshi

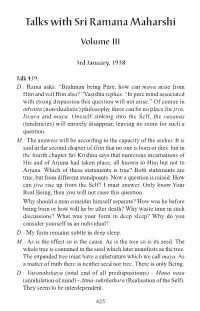

Talks with Sri Ramana Maharshi Volume III 3rd January, 1938 Talk 439. D.: Rama asks: “Brahman being Pure, how can maya arise from Him and veil Him also? “Vasishta replies: “In pure mind associated with strong dispassion this question will not arise.” Of course in advaita (non-dualistic) philosophy there can be no place for jiva, Isvara and maya. Oneself sinking into the Self, the vasanas (tendencies) will entirely disappear, leaving no room for such a question. M.: The answers will be according to the capacity of the seeker. It is said in the second chapter of Gita that no one is born or dies: but in the fourth chapter Sri Krishna says that numerous incarnations of His and of Arjuna had taken place, all known to Him but not to Arjuna. Which of these statements is true? Both statements are true, but from different standpoints. Now a question is raised: How can jiva rise up from the Self? I must answer. Only know Your Real Being, then you will not raise this question. Why should a man consider himself separate? How was he before being born or how will he be after death? Why waste time in such discussions? What was your form in deep sleep? Why do you consider yourself as an individual? D.: My form remains subtle in deep sleep. M.: As is the effect so is the cause. As is the tree so is its seed. The whole tree is contained in the seed which later manifests as the tree. The expanded tree must have a substratum which we call maya. -

The Six Systems of Vedic Philosophy

The six systems of Vedic philosophy compiled by Suhotra Swami Table of contents: 1. Introduction 2. Nyaya: The Philosophy of Logic and Reasoning 3. Vaisesika: Vedic Atomic Theory 4. Sankhya: Nontheistic Dualism 5. Yoga: Self-Discipline for Self-Realization 6. Karma-mimamsa: Elevation Through the Performance of Duty 7. Vedanta: The Conclusion of the Vedic Revelation 1. Introduction The word veda means "knowledge." In the modern world, we use the term "science" to identify the kind of authoritative knowledge upon which human progress is based. To the ancient people of Bharatavarsha (Greater India), the word veda had an even more profound import that the word science has for us today. That is because in those days scientific inquiry was not restricted to the world perceived by the physical senses. And the definition of human progress was not restricted to massive technological exploitation of material nature. In Vedic times, the primary focus of science was the eternal, not the temporary; human progress meant the advancement of spiritual awareness yielding the soul's release from the entrapment of material nature, which is temporary and full of ignorance and suffering. Vedic knowledge is called apauruseya , which means it is not knowledge of human invention. Vedic knowledge appeared at the dawn of the cosmos within the heart of Brahma, the lotus-born demigod of creation from whom all the species of life within the universe descend. Brahma imparted this knowledge in the form of sabda (spiritual sound) to his immediate sons, who are great sages of higher planetary systems like the Satyaloka, Janaloka and Tapaloka. -

EPISTEMOLOGY and METAPHYSICS (INDIAN and WESTERN) Directorate of Distance Education TRIPURA UNIVERSITY

EPISTEMOLOGY AND METAPHYSICS (INDIAN AND WESTERN) BA [Philosophy] First Semester Paper - I [ENGLISH EDITION] Directorate of Distance Education TRIPURA UNIVERSITY Reviewer Dr Shikha Jha Assistant Professor, Lakshmibai College, University of Delhi Authors Dr Prashant Shukla, Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy, University of Lucknow Units (1.4, 3.3, 4) © Reserved, 2015 Dr Jaspreet Kaur, Associate Professor, Trinity Institute of Professional Studies Unit (2) © Dr Jaspreet Kaur, 2015 Vikas Publishing House: Units (1.0-1.3, 1.5-1.9, 3.0-3.2, 3.4-3.8) © Reserved, 2015 Books are developed, printed and published on behalf of Directorate of Distance Education, Tripura University by Vikas Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this publication which is material, protected by this copyright notice may not be reproduced or transmitted or utilized or stored in any form of by any means now known or hereinafter invented, electronic, digital or mechanical, including photocopying, scanning, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without prior written permission from the DDE, Tripura University & Publisher. Information contained in this book has been published by VIKAS® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. and has been obtained by its Authors from sources believed to be reliable and are correct to the best of their knowledge. However, the Publisher and its Authors shall in no event be liable for any errors, omissions or damages arising out of use of this information and specifically disclaim any implied warranties or merchantability or fitness for any particular use. Vikas® is the registered trademark of Vikas® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. -

PADARTHA VIGYAN EVUM AYURVEDA ITIHAS (Philosophy and History of Ayurveda)

PADARTHA VIGYAN EVUM AYURVEDA ITIHAS (Philosophy and History of Ayurveda) Paper I - 100 Marks; Part A - 50 Marks 02 marks questions 1.Ayurveda Nirupana 1. Lakshana of Ayu, composition of Ayu. 2. Lakshana of Ayurveda. 3. Lakshana and classification of Siddhanta. 4. Introduction to basic principles of Ayurveda and their significance. Very Short Question: 02 marks 1. Define Ayu. 2. Lakshana of Ayu. 3. Synonyms of Ayu. 4. Types of Ayu. 5. Define Ayurveda. 6. Lakshana of Ayurveda. 7. Composition of Ayu. 8. Describe Sukhaayu. 9. Describe Dukha Ayu. 10. Describe Ahita Ayu. 11. Describe Hitaayu. 12. Give the definition of Ayurveda. 13. Write the Vyutpati of the word ‘Ayu’. 14. Write Nirukti of word ‘Ayu’. 15. Types of Siddhanta. 16. Give example of Sarvatantra Siddhant. 17. Give example of Pratitantra Siddhant. 18. Give example of Adhikarana Siddhant. Page 1 of 48 19. Give example of Abhyupagama Siddhant. 20. Name any four Basic Principles of Ayurveda. 2. Ayurveda Darshana Nirupana 1. Philosophical background of fundamentals of Ayurveda. 2. Etymological derivation of the word “Darshana”. Classification and general introduction to schools of Indian Philosophy with an emphasis on: Nyaya, Vaisheshika, Sankhya and Yoga. 3. Ayurveda as unique and independent school of thought (philosophical individuality of Ayurveda). 4. Padartha: Lakshana, enumeration and classification, Bhava and Abhava padartha, Padartha according to Charaka (Karana-Padartha). 21. Define word Darshana. 22. What is Darshana. 23. Etymological derivation of Darshana. 24. Types of Darshana. 25. Propounder of Vaisheshika Darshana. 26. Propounder of Shankhya Darshana. 27. Propounder of Nyay Darshana. 28. Propounder of Yoga Darshana. 29. Propounder of Purva-mimansa Darshana. -

Language and Reality: the World-View of the Nyaya-Vaisesika System of Indian Philosophy

Language and Reality: The World-View of the Nyaya-Vaisesika System of Indian Philosophy V.N. Jha, Pune No system of philosophy can be developed without the world-view of the philosopher.1 One can examine the truthfulness of this statement even in the context of Indian philosophical systems. There are six astika darshanas and three nastika darshanas. Samkhya, Yoga, Nyaya, Vaisesika, Purvamimamsa and Uttaramimamsa are the astika-darsanas and Buddhism, Jainism, and the Carvaka- darshana are the nastika-darsanas. The first six are called astika because they believe in the authoritativeness of the Vedas and the later three are called nastika because they do not accept the authority of the Vedas. The classification of astika and nastika has nothing to do with the believing and non-believing in God. There is nirisvara-samkhya and Purvamimamsa which did not accept God and Vaisesika too did not believe in God during its early development and still they are called astika-darsanas.2 Although Nyaya and Vaisesika were distinct systems of thought in their initial period of development, they started merging gradually because of coming closer and closer in their world-views and by the nineth century AD the merger seems to be very close. This can be drawn from the following statement of Jayantabhatta, the celebrated Kashmiri logician of the 9 th century AD: Vaisesikah asmad-anuyayina eva (Nyayamanjari, Ahnika I) 3 Purvamimamsa develped into three schools: Bhatta, Prabhakara and Murari. Uttaramimamsa or Vedanta manifested in various forms: Advaita, Dvaita, Visistadvaita, Bhedabheda, Acintyabhedabheda and so on. Even Advaita did not remain one. -

Paribhāṣenduśekharapradīpa

PARIBHĀṢENDUŚEKHARAPRADĪPA Translation, Explanation and Elucidiation of 37 Paribhāṣās of Śāstrārtha-sampādaka-prakaraṇa of Nāgojībhaṭṭa’s Paribhāṣenduśekhara With Commentaries from Vaidyanāthabhaṭṭa Pāyaguṇḍa’s Gadā-ṭīkā Tāttyaśāstri Patwardhana’s Bhūtī-ṭīkā Jayadeva Miśra’s Vijayā-tīkā Supported by Excerpts from Patañjali’s Vyākaraṇa-Mahābhāṣya Rishit Desai Chief Editor Prof. Shrinivasa Varakhedi Vice Chancellor, KKSU, Ramtek Executive Editor Prof. Madhusudan Penna Director, Research and Publication, KKSU, Ramtek Kavikulaguru Kalidas Sanskrit University, Ramtek Title - Paribhāṣenduśekharapradīpa Author - Rishit Desai Chief Editor - Prof. Shrinivasa Varakhedi Executive Editor - Prof. Madhusudan Penna (Copyright Publisher) Publisher - Registrar Kavikulaguru Kalidas Sanskrit University, Ramtek - 441106 Publication Year - 2020 Edition - First ISBN - 978-93-85710-75-9 Price - Rs. 699 /- Designed by - Umesh Patil Printed by - Avadhoot Graphics & Printing, Nagpur ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I take this opportunity to express my gratidude to all my teachers at the Bharatiya Sanskriti Peetham, Institute of Dharma Studies, Somaiya Vidyavihar University. I was a student at the Institute from 2010 to 2015 and all the concepts of the Sanskrit language – from the basics of the varṇa-mālā to advanced concepts of Pāṇinian grammar, have been learnt by me from its highly qualified teachers. I would like to specially acknowledge the efforts of Dr. (Mrs.) Kala Acharya, Director (Retd.), Dr. (Mrs.) Lalita Namjoshi, Principal (Retd.), Mrs. Prachi Pathak, Principal and Dr. Rudraksha Sakrikar, Asst. Professor, who not only taught me during my Masters programme but also were present to guide me even after I concluded my formal education. It was the Bharatiya Sanskriti Peetham that gave me the opportunity to teach and for that I remain indebted to it.