Six Philosophies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abhinavagupta's Portrait of a Guru: Revelation and Religious Authority in Kashmir

Abhinavagupta's Portrait of a Guru: Revelation and Religious Authority in Kashmir The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:39987948 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Abhinavagupta’s Portrait of a Guru: Revelation and Religious Authority in Kashmir A dissertation presented by Benjamin Luke Williams to The Department of South Asian Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of South Asian Studies Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts August 2017 © 2017 Benjamin Luke Williams All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Parimal G. Patil Benjamin Luke Williams ABHINAVAGUPTA’S PORTRAIT OF GURU: REVELATION AND RELIGIOUS AUTHORITY IN KASHMIR ABSTRACT This dissertation aims to recover a model of religious authority that placed great importance upon individual gurus who were seen to be indispensable to the process of revelation. This person-centered style of religious authority is implicit in the teachings and identity of the scriptural sources of the Kulam!rga, a complex of traditions that developed out of more esoteric branches of tantric "aivism. For convenience sake, we name this model of religious authority a “Kaula idiom.” The Kaula idiom is contrasted with a highly influential notion of revelation as eternal and authorless, advanced by orthodox interpreters of the Veda, and other Indian traditions that invested the words of sages and seers with great authority. -

ADVAITA-SAADHANAA (Kanchi Maha-Swamigal's Discourses)

ADVAITA-SAADHANAA (Kanchi Maha-Swamigal’s Discourses) Acknowledgement of Source Material: Ra. Ganapthy’s ‘Deivathin Kural’ (Vol.6) in Tamil published by Vanathi Publishers, 4th edn. 1998 URL of Tamil Original: http://www.kamakoti.org/tamil/dk6-74.htm to http://www.kamakoti.org/tamil/dk6-141.htm English rendering : V. Krishnamurthy 2006 CONTENTS 1. Essence of the philosophical schools......................................................................... 1 2. Advaita is different from all these. ............................................................................. 2 3. Appears to be easy – but really, difficult .................................................................... 3 4. Moksha is by Grace of God ....................................................................................... 5 5. Takes time but effort has to be started........................................................................ 7 8. ShraddhA (Faith) Necessary..................................................................................... 12 9. Eligibility for Aatma-SAdhanA................................................................................ 14 10. Apex of Saadhanaa is only for the sannyAsi !........................................................ 17 11. Why then tell others,what is suitable only for Sannyaasis?.................................... 21 12. Two different paths for two different aspirants ...................................................... 21 13. Reason for telling every one .................................................................................. -

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

Bhagavad Gita – the Timeless Science

Bhagavad Gita – The Timeless Science exactly like a big reservoir of water that Section 1 explains the essence of all Vedic literature and indeed there is no need to resort to any other literature in order to understand the science of Setting the Scene for the Course: Why should I study The Bhagavad Gita? Bhagavad Gita - The Timeless Science Bhagavad Gita is the most quintessential literature among all Vedic compositions. This composition as compiled by the great sage Vyasadeva has been endearing to all those who seek Truth, who look for perfection, who are interested in a complete science of everything irrespective of caste, creed, religion self-realization. and nationality. This holy book presents the ● Whom is Bhagavad Gita endearing to? science of life, as it is, which was originally ● In how many languages has Bhagavad Gita spoken to Arjun by Lord Krishna, the Supreme been translated? Personality of Godhead in the battlefield of ● Why is Bhagavad Gita timeless? Mahabharata approximately 5000 years ago. ● Give an analogy to compare Bhagavad Gita Through the ages, Srimad Bhagavad Gita has with other Vedic literature. inspired and guided hosts of philosophers and scientists. Its influence is not limited to India. Bhagavad Gita - The Torch-light There is not a single language in the world in of Wisdom which Bhagavad Gita has not been translated. Arjuna in the battlefield got confused about his Just like the Quran and Bible are known all duty. Like Arjuna, we are all confused about over the world, Bhagavad Gita is also known our duty. This world is a battlefield. -

Perfect Guru

Perfect Guru By H. H. Krishna Chaitanya Swami 1 Table of contents Introduction Chapter 1 Who can be called a guru? Chapter 2 Qualities and activities of guru. Chapter 3 Indra lost heaven by offending his spiritual master. Dedicated to His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Srila Prabhupada and Bhakti Svarupa Damodara Swami Srila Sripada Introducion Introduction A guru is one who disseminates transcendental knowledge among his disciples with reference to distinction of matter, spirit and Supreme Spirit, Godhead. Many teachers have tried to be gurus, but not all of them could become a guru for want of necessary qualification. To be a guru, one must be able to protect his disciples from falling down into the repeated cycle of birth, death, old age, and disease by associating the disciple with God in yoga. Guru teaches mainstream yoga practices, given in the scriptures, which unites the disciple with the Supreme Lord. A Guru does not manifest magic, gold, siddhis. He neither watch TV serials nor digital movies, and certainly does none of the prohibited acts viz. eat betel nuts, smoke ganja, and travel for amusement, eat meat, drink alcohol, has close association with females, nor gamble. He cannot be identified from a long beard and curly long hair with golden turban, a clever disguise to attract the followers. The goal of a guru is not to render dry social services in the form of hospitals and schools unless it is strongly connected to the Supreme Lord Krishna. He does not wear gold and diamond ornaments on his body, does not dance with his female disciples. -

Arsha Vidya Newsletter Rs

Arsha Vidya Newsletter Rs. 15/- Swamiji--Jnana Biksha Vol. 17 May 2016 Issue 5 2.Pujya Swamiji with Swami Chinmayanandaji2.Pujya Swamiji with Swami Chinmayanandaji Ramanavami at AVG 2 Arsha Vidya Newsletter - May 2016 1 Arsha Vidya Pitham Dr.V.Prathikanti,G.S.Raman Swami Dayananda Ashram Trustees: Dr.L.Mohan rao, Dr Bhagabat sahu, Sri Gangadhareswar Trust Ramesh Bhaurao Girde Rakesh Sharma,V.B.Somasundaram Purani Jhadi, Rishikesh Avinash Narayanprasad Pande and Bhagubhai Tailor. Pin 249 201, Uttarakhanda Madhav Chintaman Kinkhede Ph.0135-2431769 Ramesh alias Nana Pandurang Arsha Vidya Gurukulam Gawande Fax: 0135 2430769 Rajendra Wamanrao Korde Institute of Vedanta and Sanskrit Sruti Website: www.dayananda.org Swamini Brahmaprakasananda Seva Trust Email: [email protected] Anaikatti P.O., Coimbatore 641108 Tel. Arsha Vidya Gurukulam 0422-2657001 Board of Trustees: Institute of Vedanta and Sanskrit Fax 91-0422-2657002 P.O. Box No.1059 Web Site http://www.arshavidya.in Founder : Saylorsburg, PA, 18353, USA Email: [email protected] Brahmaleena Pujya Sri Tel: 570-992-2339 Swami Dayananda Fax: 570-992-7150 Board of Trustees: Saraswati 570-992-9617 Web Site : http://www.arshavidhya.org Founder: Chairman & BooksDept:http://books.arshavidya.org Brahmaleena Pujya Sri Managing Trustee: Swami Dayananda Saraswati Swami Suddhananda Board of Trustees: Saraswati Paramount Trustee: Founder : Vice Chairman: Brahmaleena Pujya Sri Swami Sadatmananda Saraswati Swami Tattvavidananda Swami Dayananda Swami Shankarananda Saraswati Saraswati Saraswati Trustee & Acharya: President: Chairman: Swami Santatmananda Swami Viditatmananda Saraswati R. Santharam Saraswati Vice Presidents: Trustees: Swami Tattvavidananda Saraswati Trustees: Swami Jnanananda Swami Pratyagbodhanada C. Soundar Raj Saraswati Saraswati P.R.Ramasubrahmaneya Rajhah Sri M.G. -

An Understanding of Maya: the Philosophies of Sankara, Ramanuja and Madhva

An understanding of Maya: The philosophies of Sankara, Ramanuja and Madhva Department of Religion studies Theology University of Pretoria By: John Whitehead 12083802 Supervisor: Dr M Sukdaven 2019 Declaration Declaration of Plagiarism 1. I understand what plagiarism means and I am aware of the university’s policy in this regard. 2. I declare that this Dissertation is my own work. 3. I did not make use of another student’s previous work and I submit this as my own words. 4. I did not allow anyone to copy this work with the intention of presenting it as their own work. I, John Derrick Whitehead hereby declare that the following Dissertation is my own work and that I duly recognized and listed all sources for this study. Date: 3 December 2019 Student number: u12083802 __________________________ 2 Foreword I started my MTh and was unsure of a topic to cover. I knew that Hinduism was the religion I was interested in. Dr. Sukdaven suggested that I embark on the study of the concept of Maya. Although this concept provided a challenge for me and my faith, I wish to thank Dr. Sukdaven for giving me the opportunity to cover such a deep philosophical concept in Hinduism. This concept Maya is deeper than one expects and has broaden and enlightened my mind. Even though this was a difficult theme to cover it did however, give me a clearer understanding of how the world is seen in Hinduism. 3 List of Abbreviations AD Anno Domini BC Before Christ BCE Before Common Era BS Brahmasutra Upanishad BSB Brahmasutra Upanishad with commentary of Sankara BU Brhadaranyaka Upanishad with commentary of Sankara CE Common Era EW Emperical World GB Gitabhasya of Shankara GK Gaudapada Karikas Rg Rig Veda SBH Sribhasya of Ramanuja Svet. -

Vaisnava Calendar 2008 Krishna Bhakti Magazine

Disclaimer: This calendar is calculated Krishna Bhakti Magazine for Radhadesh and Amsterdam. For more precise details of your location, Vaisnava Calendar 2008 Radhadesh • Château de Petite Somme • 6940 Septon (Durbuy) • Belgium • (+) 32 (0)86 32 29 26 • [email protected] please consult: vcal.iskcongbc.org January February March April May June 3 Th Fasting for Saphala Ekadasi 2 Sa Fasting for Sat-tila Ekadasi 3 Mo Fasting for Vijaya Ekadasi 2 We Fasting for Papamocani Ekadasi 1 Th Fasting for Varuthini Ekadasi 1 Su Break fast 05:32 - 08:38 Sri Devananda Pandita (disappearance) 3 Su Break fast 08:37 - 11:18 4 Tu Break fast 07:19 - 10:58 3 Th Break fast 07:10 - 11:31 2 Fr Break fast 08:10 - 11:07 Srila Vrndavana Dasa Thakura 4 Fr Break fast 08:50 - 11:21 11 Mo Vasanta Pancami Sri Isvara Puri (disappearance) Sri Govinda Ghosh (disappearance) 5 Mo Sri Gadadhara Pandita (appearance) (appearance) 5 Sa Sri Mahesa Pandita (disappearance) Srimati Visnupriya Devi (appearance) 6 Th Siva-ratri 10 Th Sri Ramanujacarya (appearance) 8 Th Candana-yatra starts (continues for 21 days) 13 Fr Sri Baladeva Vidyabhusana Sri Uddharana Datta Thakura Sarasvati-puja 8 Sa Srila Jagannatha Dasa Babaji 13 Su Beginning of Salagrama and Tulasi Aksaya Tritiya (day for new beginnings) (disappearance) (disappearance) Srila Visvanatha Cakravarti Thakura (disappearance) Jala Dana 11 Su Jahnu Saptami Ganga Puja 9 We Sri Locana Dasa Thakura (appearance) (disappearance) Sri Rasikananda (disappearance) 14 Mo Rama Navami: Appearance of Lord 13 Tu Srimati Sita Devi (consort -

19. Sarasaram V1

Sincere Thanks To: 1. The Editor-in-Chief of SrI hayagrivan eBooks - "SrI nrusimha seva rasikan" Oppiliappan Koil SrI Varadachari SaThakopan Swamy - for kindly hosting this title in his eBooks series 2. Mannargudi SrI Srinivasan Narayanan Swamy for proof reading 3. Sri N.Santhanakrishnan (http://www.thiruvarangam.com) for all pictures relating to the divyadesams of SrIrangam, Thiruvellarai, Thiru Anbil, ThirunAngur kshetrams and Thirukarambanur, except where otherwise indicated. sadagopan.org 4. Nedumtheru SrI Mukund SrInivasan, SrI Murali BhaTTar, SrI Ramakrishna Deekshitulu, SrI Diwakar Kannan, www.pbase.com, SrI Srikanth Veeraraghavan, SrI Achutharaman, SrI Prabhu and SrI Lakshminarasimhan Sridhar for all other images. 5. Sou R. Chitralekha for providing beautiful artwork for the eBook 6. Smt Jayashree Muralidharan for eBook assembly C O N T E N T S Introduction - Editors Note 1 Author's Introduction 9 The Importance of Thirumantra 15 The Eminence of Thirumantra 25 The Arrangement of Syllables in the Thirumantra 51 The Significance of the ‘a’ in PraNava 71 The Significance of the ‘u’ in PraNava 110 sadagopan.org The Significance of the ‘m’ in PraNava 119 The Significance of ‘namah’ 145 The Significance of ‘nArAyaNanAya’ 193 The Meaning of the Thirumanthiram as a Whole 265 Bibliography 282 sadagopan.org NamperumAl - SrIrangam . ïI>. INTRODUCTORY NOTE by Oppiliappan Koil SrI VaradAchAri Sadagopan Swamy NigamAnta MahA Desikan's vAtsalyam for us, the samsAris, led to the creation of many Sri sUktis dealing with the sacred Rahasyatrayams rooted in authentic PramANams. The most elaborate Sri sUkti of Swamy Desikan is Srimad Rahasya traya sAram dealing with the extensive coverage of the three sadagopan.org Rahasyams -- mUla mantram, dvayam and carama SlOkam -- for our upAya-phala pUrti. -

Neuroscience of the Yogic Theory of Mind and Consciousness

1 Neuroscience of the Yogic Theory of 2 Mind and Consciousness 3 Vaibhav Tripathi1* and Pallavi Bharadwaj2 *For correspondence: [email protected] (VT) 4 1Boston University; 2Massachusetts Institute of Technology † Present address: Department of 5 Psychological and Brain Sciences, Boston University, Boston, MA, ‡ USA 02215; Laboratory for 6 Abstract Yoga as a practice and philosophy of life has been followed for more than 4500 years Information and Decision Systems, 7 Massachusetts Institute of with known evidence of Yogic practices in the Indus Valley Civilization. A plethora of scholars have Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139 8 contributed to the development of the field, but in last century the profound knowledge 9 remained inaccessible and incomprehensible to the general public. Last few decades have seen a 10 resurgence in the utility of Yoga and Meditation as a practice with growing scientific evidence 11 behind it. Significant scientific literature has been published, illustrating the benefits of Yogic 12 practices including asana, pranayama and dhyana on mental and physical well being. 13 Electrophysiological and recent functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) studies have 14 found explicit neural signatures for Yogic practices. In this article, we present a review of the 15 philosophy of Yoga, based on the dualistic Sankhya school, as applied to consciousness 16 summarized by Patanjali in his Yoga Sutras followed by discussion on the five vritti (modulations 17 of mind), practice of pratyahara, dharana, dhyana, different states of samadhi, and samapatti. We 18 introduce Yogic Theory of Mind and Consciousness (YTMC), a cohesive theory that can model 19 both external modulations and internal states of the mind. -

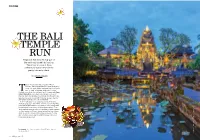

THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali Share the Top Spot on the Must-Visit List with Its Beaches

CULTURE THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali share the top spot on the must-visit list with its beaches. Take a look at some of these architectural marvels that dot the pretty Indonesian island. TEXT ANURAG MALLICK he sun was about to set across the cliffs of Uluwatu, the stony headland that gave the place its name. Our guide, Made, explained that ulu is ‘land’s end’ or ‘head’ in Balinese, while watu is ‘stone’. PerchedT on a rock at the southwest tip of the peninsula, Pura Luhur Uluwatu is a pura segara (sea temple) and one of the nine directional temples of Bali protecting the island. We gaped at the waves crashing 230 ft below, unaware that the real spectacle was about to unfold elsewhere. A short walk led us to an amphitheatre overlooking the dramatic seascape. In the middle, around a sacred lamp, fifty bare-chested performers sat in concentric rings, unperturbed by the hushed conversations of the packed audience. They sat in meditative repose, with cool sandalwood paste smeared on their temples and flowers tucked behind their ears. Sharp at six, chants of cak ke-cak stirred the evening air. For the next one hour, we sat open-mouthed in awe at Bali’s most fascinating temple ritual. Facing page: Pura Taman Saraswati is a beautiful water temple in the heart of Ubud. Elena Ermakova / Shutterstock.com; All illustrations: Shutterstock.com All illustrations: / Shutterstock.com; Elena Ermakova 102 JetWings April 2017 JetWings April 2017 103 CULTURE The Kecak dance, filmed in movies such as There are four main types of temples in Bali – public Samsara and Tarsem Singh’s The Fall, was an temples, village temples, family temples for ancestor worship, animated retelling of the popular Hindu epic and functional temples based on profession. -

Book Only Cd Ou160053>

TEXT PROBLEM WITHIN THE BOOK ONLY CD OU160053> Vedant series. Book No. 9. English aeries (I) \\ A hand book of Sri Madhwacfaar^a's POORNA-BRAHMA PH I LOSOPHY by Alur Venkat Rao, B.A.LL,B. DHARWAR. Dt. DHARWAR. (BOM) Publishers : NAYA-JEEYAN GRANTHA-BHANDAR, SADHANKERI, DHARWAR. ( S.Rly ) Price : Superior : 7 Rs. 111954 Ordinary: 6 Rs. (No postage} Publishers: Nu-va-Jeevan Granth Bhandar Dharwar, (Bombay) Printer : Sri, S. N. Kurdi, Sri Saraswati Printing Press, Dharwar. ,-}// rights reserved by the author. To Poorna-Brahma Dasa; Sri Sri : Sri Madhwacharya ( Courtesy 1 he title of my book is rather misleading for though the main theme of the book is Madhwa philosophy, it incidentally and comparitively deals with other philosophies such as that of Sri Shankara Sri Ramanuja and Sri Mahaveer etc. So, it is use- ful for all those who are interested in such subjects. Sri Madhawacharya, the foremost Vaishnawa philosopher, who is the last of the three great Teachers,- Sri Shankara, Sri Ramanuja and Sri Madhwa,- is so far practically unknown to the English-reading public of India. This is, therefore the first attempt to present his philosophy to the wider public. Madhwa philosophy has got two aspects, one universal and the other, particular. I have tried to place before the readers both these aspects. I have re-assessed the values of Madhwa and other philosophies, and have tried to find out also the greatest common factor,-an angle of vision which has not been systematically adopted by any body. He is a great Harmoniser. In fact mine isS quite a new approach, I have tried to put old things in a new way.