Fascinating Flags of Plundering Pirates and Profiteering Privateers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Welcome from the Dais ……………………………………………………………………… 1 Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Background Information ……………………………………………………………………… 3 The Golden Age of Piracy ……………………………………………………………… 3 A Pirate’s Life for Me …………………………………………………………………… 4 The True Pirates ………………………………………………………………………… 4 Pirate Values …………………………………………………………………………… 5 A History of Nassau ……………………………………………………………………… 5 Woodes Rogers ………………………………………………………………………… 8 Outline of Topics ……………………………………………………………………………… 9 Topic One: Fortification of Nassau …………………………………………………… 9 Topic Two: Expulsion of the British Threat …………………………………………… 9 Topic Three: Ensuring the Future of Piracy in the Caribbean ………………………… 10 Character Guides …………………………………………………………………………… 11 Committee Mechanics ……………………………………………………………………… 16 Bibliography ………………………………………………………………………………… 18 1 Welcome from the Dais Dear delegates, My name is Elizabeth Bobbitt, and it is my pleasure to be serving as your director for The Republic of Pirates committee. In this committee, we will be looking at the Golden Age of Piracy, a period of history that has captured the imaginations of writers and filmmakers for decades. People have long been enthralled by the swashbuckling tales of pirates, their fame multiplied by famous books and movies such as Treasure Island, Pirates of the Caribbean, and Peter Pan. But more often than not, these portrayals have been misrepresentations, leading to a multitude of inaccuracies regarding pirates and their lifestyle. This committee seeks to change this. In the late 1710s, nearly all pirates in the Caribbean operated out of the town of Nassau, on the Bahamian island of New Providence. From there, they ravaged shipping lanes and terrorized the Caribbean’s law-abiding citizens, striking fear even into the hearts of the world’s most powerful empires. Eventually, the British had enough, and sent a man to rectify the situation — Woodes Rogers. In just a short while, Rogers was able to oust most of the pirates from Nassau, converting it back into a lawful British colony. -

975 Bacons Bridge

Your #1 Source For Patriotic Goods! 975 Bacons Bridge Rd., Suite 148-152, Summerville, SC 29485 www.patriotic-flags.com 1-866-798-2803 All flags are 3’x5’, silk-screened polyester, have two brass grommets, and cost only $13.00 postpaid. (unless otherwise noted). Gadsden Viking Raven Banner Jolly Roger U.S. Marine Corp Culpeper Vinland Irish American POW *MIA Colonial Navy Jack French Fleur de lis Russian Czar Welcome Home Grand Union Blue Service Star East Flanders Imperial German Jack Bunker Hill 34 Star (Civil War) UK Royal Standard Munster Betsy Ross 35 Star (Civil War) German Parliamentary Royal Swedish All 3’x5’ Polyester flags only $13.00 postage paid. Free shipping in the US and Canada. South Carolina residents receive a discount equal to sales tax. All polyester flags have two rows of stitching per side and most have four rows on the fly for extra strength in high wind. All flags have two brass grommets. All flags look the same on both sides. Most world flags and military flags are also available in 2’x3’ for $11.00 postage paid. Some flags are also available in 4’x6’ for $25.00 postage paid. Other types of flags we sell. 3’x5’ Sewn Cotton flags for $45.00. 3’x5’ Sewn Synthetic flags for $35.00. We have extra heavy duty 3’x5’ sewn nylon flags (all lettering is the correct orientation on both sides) for the branches of the military and POW*MIA flags for $45.00. All prices include shipping in the US & Canada. We sell over 1,000 different flags. -

17 Pirates.Cdr

8301EdwardEngland,originunknown, Pirates’ flags (JollyRoger)ofthe17thcenturypiracy. wasstrandedinMadagaskar1720 byJohn Tayloranddiedthere Someofthepirateshadsmallfleetsofships shorttimelaterasapoorman. thatsailedundertheseflags. Lk=18mm=1,80 € apiece Afterasuccessfulcounteractionbymanycountries Lk=28mm=2,20 € apiece thiskindofpiracyabatedafter1722. Lk=38mm=3,60 € apiece Lk=80mm=6,50 € apiece 8303JackRackam(CalicoJack), wasimprisonedtogetherwith 8302HenryEvery, theamazones AnneBonnyand bornaround1653,wascalledlater MaryRead.Washangedin1720. BenjaminBridgeman,wasnevercaught Lk=18mm=1,80 € apiece anddiedinthefirstquarter Lk=28mm=2,20 € apiece of18thcenturysomewhereinEngland. Lk=38mm=3,20 € apiece Lk=18mm=1,80 € apiece Lk=45mm=3,80 € apiece Lk=28mm=2,20 € apiece Lk=50mm=4,20 € apiece Lk=38mm=3,20 € apiece 8305 Thomas Tew, piratewithaprivateeringcommision fromthegovernorofBermuda, 8304RichardWorley, hedied1695inafightwhile littleisknownabouthim. boardinganIndianmerchantship. Lk=18mm=1,80 € apiece Lk=18mm=1,80 € apiece Lk=28mm=2,20 € apiece Lk=28mm=2,20 € apiece Lk=38mm=3,20 € apiece Lk=38mm=3,20 € apiece Lk=70mm=5,60 € apiece 8306ChristopherCondent, hecapturedahuge Arabshipwitharealtreasure in1719nearBombay. Asaresultheandmostof hiscrewgaveuppiracyandnegotiatedapardon withtheFrenchgovernorofReunion.Condent marriedthegovernor’ssisterinlawandlater 8307Edward Teach,namedBlackbeard, settledaswelltodoshipownerinFrance. oneofthemostfearedpiratesofhistime. Lk=15mm=1,90 € apiece Hediedin1718inagunfight Lk=18mm=2,25 € apiece duringhiscapture. Lk=28mm=2,60 -

Blood & Bounty

A short life but a merry one! A 28mm “Golden Age of Piracy” Wargame by DonkusGaming Version 1.0 Contents: Setting up a Game pg. 2 A very special “Thank You” to my art resources: Sequence of Play pg. 3 http://www.eclipse.net/~darkness/sail-boat-01.png https://math8geometry.wikispaces.com/file/view/protractor.gif/3 3819765/protractor.gif Vessel Movement Details pg. 7 http://brethrencoast.com/ship/sloop.jpg, Vessel Weapon Details pg. 8 http://brethrencoast.com/ship/brig.jpg, Vessel Weapons & Tables pg. 9 http://brethrencoast.com/ship/frigate.jpg, http://brethrencoast.com/ship/manofwar.jpg, Vessel Classes & Statistics pg. 11 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_ensign, Vessel Actions pg. 16 http://www.crwflags.com/fotw/flags/fr~mon.html, http://www.crwflags.com/fotw/flags/es~c1762.html, Crew Actions pg. 22 http://www.crwflags.com/fotw/flags/es_brgdy.html, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jolly_Roger, Crew Weapons (Generic) pg. 26 http://www.juniorgeneral.org/donated/johnacar/napartTD.png Crew Statistics pg. 29 https://jonnydoodle.files.wordpress.com/2012/06/alp ha.jpg http://www.webweaver.nu/clipart/img/historical/pirates/xbones- Famous Characters & Crews pg. 34 black.png Running a Campaign pg. 42 http://www.imgkid.com/ http://animal-kid.com/pirate-silhouette-clip-art.html Legal: The contents of this strategy tabletop miniatures game “Blood & Bounty” (excluding art resources where listed) are the sole property of myself, Liam Thomas (DonkusGaming) and may not be reproduced in part or as a whole under any circumstances except for personal, private use. They may not be published within any website, blog, or magazine, etc., or otherwise distributed publically without advance written permission (see email address listed below.) Use of these documents as a part of any public display without permission is strictly prohibited, and a violation of the author’s rights. -

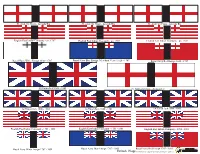

British Flags Permission to Copy for Personal Gaming Use Granted GAME STUDIOS

St AndrewsSt. Andrews Cross – CrossEnglish - Armada fl ag of the Era Armada Era St AndrewsSt. Andrews Cross – Cross English - Armada fl ag of the Era Armada Era St AndrewsSt. Andrews Cross – EnglishCross - flArmada ag of the Era Armada Era EnglishEnglish East IndianIndia Company Company - -pre pre 1707 1707 EnglishEnglish East East Indian India Company - pre 1707 EnglishEnglish EastEast IndianIndia Company Company - - pre pre 1707 1707 Standard Royal Navy Blue Squadron Ensign, Royal Navy White Ensign 1630 - 1707 Royal Navy Blue Ensign /Merchant Vessel 1620 - 1707 RoyalRoyal Navy Navy Red Red Ensign Ensign 1620 1620 - 1707 - 1707 1st Union Jack 1606 - 1801 St. Andrews Cross - Armada Era 1st1st UnionUnion fl Jackag, 1606 1606 - -1801 1801 1st1st Union Union Jack fl ag, 1606 1606 - 1801- 1801 1st1st Union Union fl Jackag, 1606 1606 - -1801 1801 English East Indian Company - 1701 - 1801 English East Indian Company - 1701 - 1801 English East Indian Company - 1701 - 1801 Royal Navy White Ensign 1707 - 1801 Royal Navy Blue Ensign 1707 - 1801 RoyalRed Navy Ensign Red as Ensignused by 1707 Royal - 1801Navy and ColonialSEA subjects DOG GAME STUDIOS British Flags Permission to copy for personal gaming use granted GAME STUDIOS . Dutch East India company fl ag Dutch East India company fl ag Dutch East India company fl ag Netherlands fl ag Netherlands fl ag Netherlands fl ag Netherlands Naval Jack Netherlands Naval Jack Netherlands Naval Jack Dutch East India company fl ag Dutch East India company fl ag Dutch East India company fl ag Netherlands fl ag Netherlands fl ag Netherlands fl ag SEA DOG Dutch Flags GAME STUDIOS Permission to copy for personal gaming use granted. -

Archaeology of Piracy Between Caribbean Sea and the North American Coast of 17Th and 18Th Centuries: Shipwrecks, Material Culture and Terrestrial Perspectives

Journal of Caribbean Archaeology Copyright 2019 ISBN 1524-4776 ARCHAEOLOGY OF PIRACY BETWEEN CARIBBEAN SEA AND THE NORTH AMERICAN COAST OF 17TH AND 18TH CENTURIES: SHIPWRECKS, MATERIAL CULTURE AND TERRESTRIAL PERSPECTIVES Jean Soulat Laboratoire LandArc – Centre Michel de Boüard, Craham UMR 6273 Groupe de Recherche en Archéométrie, Université Laval, Québec 29, rue de Courbuisson 77920 Samois-sur-Seine – France [email protected] John de Bry Center for Historical Archaeology 140 Warsteiner Way, Suite 204 Melbourne Beach, Florida 32951 – USA [email protected] The archaeology of piracy in the 17th and 18th centuries remains a poorly developed discipline in the world. American universities in connection with local authorities were the first to fund and support such research programs on the east coast of the United States and the Caribbean. The study of the shipwreck of the pirate Edward Teach (Blackbeard), the Queen Anne's Revenge 1718, is a very good example of this success. However, a work of crossing archaeological data deserves to be carried out for all the sites brought to light, in particular in the Caribbean area, on the North American coast, without forgetting the Indian Ocean. The synthetic work of Charles R. Ewen and Russell K. Skowronek published in 2006 and 2016 by the University of Florida is an important first step. They treat shipwrecks as well as land occupations, and go back for a long time on the percceived ideas related to the true image of Pirates. However, there is a lack of material culture studies from these sites probably related to the lack of scientific publications of these objects. -

Life Under the Jolly Roger: Reflections on Golden Age Piracy

praise for life under the jolly roger In the golden age of piracy thousands plied the seas in egalitarian and com- munal alternatives to the piratical age of gold. The last gasps of the hundreds who were hanged and the blood-curdling cries of the thousands traded as slaves inflated the speculative financial bubbles of empire putting an end to these Robin Hood’s of the deep seas. In addition to history Gabriel Kuhn’s radical piratology brings philosophy, ethnography, and cultural studies to the stark question of the time: which were the criminals—bankers and brokers or sailors and slaves? By so doing he supplies us with another case where the history isn’t dead, it’s not even past! Onwards to health-care by eye-patch, peg-leg, and hook! Peter Linebaugh, author of The London Hanged, co-author of The Many-Headed Hydra This vital book provides a crucial and hardheaded look at the history and mythology of pirates, neither the demonization of pirates as bloodthirsty thieves, nor their romanticization as radical communitarians, but rather a radical revisioning of who they were, and most importantly, what their stories mean for radical movements today. Derrick Jensen, author of A Language Older Than Words and Endgame Stripping the veneers of reactionary denigration and revolutionary romanti- cism alike from the realities of “golden age” piracy, Gabriel Kuhn reveals the sociopolitical potentials bound up in the pirates’ legacy better than anyone who has dealt with the topic to date. Life Under the Jolly Roger is important reading for anyone already fascinated by the phenomena of pirates and piracy. -

The Pirates Christopher Condent an English Pirate Known for His Brutal Treatment of Prisoners, Sailed the Seas in the Early to Mid 1700’S

TM Rules The Pirates Christopher Condent An English pirate known for his brutal treatment of prisoners, sailed the seas in the early to mid 1700’s. His exploits ranged from the coast of Brazil to India and the Red Sea. He died in 1770. Jack Rackham Known as Calico Jack for the brightly colored coats and clothing he wore, Rackham was a classic Caribbean pirate, capturing small merchant vessels. After being pardoned once, he returned to piracy and was tried and hanged in Port Royal, Jamaica, in November of 1720. Henry Avery Sailing the Atlantic and Indian Oceans in the 1690’s, Avery was known at one time to be the richest pirate in the world. He is also famous for being one of the few pirates to retain his wealth and retire before either being killed in battle or tried and hanged. Emanuel Wynn This French Pirate is considered by many to be the first to fly the familiar skull and crossbones or ‘Jolly Roger’ flag. He also incorporated the image of an hourglass to tell his victims that time was running out. Playing the Game Goal: The goal of the game is to make three X’s out of your Pirate icons. Setting up the Game: You will need a large flat surface to play. Take the four Pirate Flag Cards (shown on page one) and shuffle them. Each player takes one and does not show it to the other players. The flag you drew is your icon. Keep this face down in front of you. Now, Ghost ship: A wild shuffle the deck and deal four cards face down to each player. -

Research Ranger--Pirates: a Bibliography of Multnomah County Library Resources

Research Ranger--Pirates: A bibliography of Multnomah County Library resources AUTHOR Adkins, Jan. TITLE What if you met a pirate? : an historical voyage of seafaring speculation / written & illustrated by Jan Adkins. PUB INFO Brookfield, Ct. : Roaring Brook Press, c2004. CALL # j 910.45 A236w 2004. AUTHOR Davis, Kelly. TITLE See-through pirates / Kelly Davis. PUB INFO Philadelphia, PA : Running Press Kids, 2003. CALL # j 910.45 D262s 2003. AUTHOR Dennis, Peter, 1950- TITLE Shipwreck / illustrated by Peter Dennis ; [text, Claire Aston]. PUB INFO Hauppauge, NY : Barron's Educational Series, Inc., c2001. CALL # j 910.452 D411s 2001. AUTHOR Gibbons, Gail. TITLE Pirates : robbers of the high seas / Gail Gibbons. PUB INFO Boston : Little, Brown, c1993. CALL # j 910.45 G441p. AUTHOR Harward, Barnaby. TITLE The best book of pirates / Barnaby Harward. PUB INFO New York : Kingfisher, 2002. CALL # j 910.45 H343b 2002. AUTHOR Kallen, Stuart A., 1955- TITLE Life among the pirates / by Stuart A. Kallen. PUB INFO San Diego, CA : Lucent Books, c1999. CALL # j 910.45 K14L 1999. AUTHOR Lincoln, Margarette. TITLE The pirate's handbook / Margarette Lincoln. PUB INFO New York, N.Y. : Cobblehill Books, c1995. CALL # j 910.45 L738p. AUTHOR Lock, Deborah. TITLE Pirate / written by Deborah Lock. PUB INFO New York, NY : DK Pub., 2005. CALL # j 910.45 L813p 2005. AUTHOR Malam, John, 1957- TITLE How to be a pirate / written by John Malam ; illustrated by Dave Antram. PUB INFO Washington, D.C. : National Geographic, 2005. CALL # j 910.45 M236h 2005. AUTHOR Maynard, Christopher. TITLE Pirates! : raiders of the high seas / written by Christopher Maynard. -

The Alliance of Pirates : Ireland and Atlantic Piracy in the Early Seventeenth Century Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE ALLIANCE OF PIRATES : IRELAND AND ATLANTIC PIRACY IN THE EARLY SEVENTEENTH CENTURY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Connie Kelleher | 552 pages | 29 May 2020 | Cork University Press | 9781782053651 | English | Cork, Ireland The Alliance of Pirates : Ireland and Atlantic Piracy in the Early Seventeenth Century PDF Book Main article: A General History of the Pyrates. Other ranks include the boatswain, master, gunner, doctor, and carpenter. If a pirate were to take more than his share, hide in times of war, or was dishonest with the crew, he "risked being deposited" somewhere unpleasant and full of hardships. Right before he swung off to his death he delivered a warning to all ships captains and owners that in order to prevent their crews from mutinying and resorting to piracy, they would be wise to pay their crews on time and treat them humanly. For pirates in the Atlantic World, trade routes are fortuitous, because of the vast wealth they supply in the way of cargo that moved along the Middle Passage. The captors were already "familiar with the single-sex community of work and the rigors of life-and death-at sea. Governments would stop turning a blind eye to these bandits when the costs of ignoring them outweighed attacking the pirate, and so a "campaign to cleanse the seas," was put into effect by governments, lawyers, businessmen, writers, and other members of legitimate society. Pirates were mostly former merchant seamen, or at least men who had sailed on vessels legitimately before turning to piracy. These were usually granted to ships which had been attacked so they could regain their property. -

Pirate Articles and Their Society, 1660-1730

‘Piratical Schemes and Contracts’: Pirate Articles and their Society, 1660-1730 Submitted by Edward Theophilus Fox to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Maritime History In May 2013 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………………………………………………………….. 1 Abstract During the so-called ‘golden age’ of piracy that occurred in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans in the later seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, several thousands of men and a handful of women sailed aboard pirate ships. The narrative, operational techniques, and economic repercussions of the waves of piracy that threatened maritime trade during the ‘golden age’ have fascinated researchers, and so too has the social history of the people involved. Traditionally, the historiography of the social history of pirates has portrayed them as democratic and highly egalitarian bandits, divided their spoil fairly amongst their number, offered compensation for comrades injured in battle, and appointed their own officers by popular vote. They have been presented in contrast to the legitimate societies of Europe and America, and as revolutionaries, eschewing the unfair and harsh practices prevalent in legitimate maritime employment. This study, however, argues that the ‘revolutionary’ model of ‘golden age’ pirates is not an accurate reflection of reality. -

Origins, Motives, and Political Sentiments, C.1716-1726

Occam's Razor Volume 10 (2020) Article 6 2020 Piratical Actors: Origins, Motives, and Political Sentiments, c.1716-1726 Corey Griffis Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/orwwu Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Griffis, Corey (2020) "Piratical Actors: Origins, Motives, and Political Sentiments, c.1716-1726," Occam's Razor: Vol. 10 , Article 6. Available at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/orwwu/vol10/iss1/6 This Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Western Student Publications at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occam's Razor by an authorized editor of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Griffis: Piratical Actors: Origins, Motives, and Political Sentiments, c.1 PIRATICAL ACTORS Origins, Motives, and Political Sentiments, c. 1716-1726 By Corey Griffis n the middle months of the year 1720, Clement Downing arrived at the settlement of Saint Augustin in Mad- Iagascar, a midshipman aboard the Salisbury on its journey to trade in India. Led by ex-pirate John Rivers from 1686-1719, Saint Augustin was well-known as a resupplying depot for pirates operating in the region and, like other settlements in the immediate vicinity, was populated by “30 to 50 ex-pirates, or men waiting for a ship.”1 As ex-pirates, these men were said to have had “a very open-handed fraternity” with the Indigenous Malagasy populations; on rare occasions, the ex-pirates traded for enslaved people captured in local warfare and sold them to passing sailors or merchants.