The Calculus of Piratical Consent: the Myth of the Myth of Social Contract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A General Model of Illicit Market Suppression A

ALL THE SHIPS THAT NEVER SAILED: A GENERAL MODEL OF ILLICIT MARKET SUPPRESSION A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Government. By David Joseph Blair, M.P.P. Washington, DC September 15, 2014 Copyright 2014 by David Joseph Blair. All Rights Reserved. The views expressed in this dissertation do not reflect the official policy or position of the United States Air Force, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. ii ALL THE SHIPS THAT NEVER SAILED: A GENERAL MODEL OF TRANSNATIONAL ILLICIT MARKET SUPPRESSION David Joseph Blair, M.P.P. Thesis Advisor: Daniel L. Byman, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This model predicts progress in transnational illicit market suppression campaigns by comparing the relative efficiency and support of the suppression regime vis-à-vis the targeted illicit market. Focusing on competitive adaptive processes, this ‘Boxer’ model theorizes that these campaigns proceed cyclically, with the illicit market expressing itself through a clandestine business model, and the suppression regime attempting to identify and disrupt this model. Success in disruption causes the illicit network to ‘reboot’ and repeat the cycle. If the suppression network is quick enough to continually impose these ‘rebooting’ costs on the illicit network, and robust enough to endure long enough to reshape the path dependencies that underwrite the illicit market, it will prevail. Two scripts put this model into practice. The organizational script uses two variables, efficiency and support, to predict organizational evolution in response to competitive pressures. -

BLACK JACKS Written by Eric Karkheck

BLACK JACKS Written By Eric Karkheck (323) 736-6718 [email protected] Black Jack: noun, 18th Century An African warrior who becomes a pirate. FADE IN: EXT. VILLAGE BEACH, WEST AFRICA - DAY Statuesque TERU FURRO (30s) sits in the sand braiding ropes together into a fishing net. She is left handed because her right is missing its pinky finger. She looks out to the vast ocean. EXT. HIDDEN LAGOON - DAY Blue sky and puffy clouds reflect in the surface of the water. A dugout canoe with a sail skims across it. Tall and muscular CHAGA FURRO (30s) paddles in the stern. His skinny son KUMI (13) is in the bow. Chaga spots a school of tilapia. CHAGA Kumi, mind the net. (Note: Italicized dialogue is spoken in Akan African and subtitled in English.) KUMI Yes, father. Kumi gathers the net into his arms. CHAGA Do it clean. If the lines tangle it will scatter the school. Kumi throws the net overboard. He pulls in the ropes. KUMI They are strong. The ropes zip through Kumi's hands. Chaga catches them. CHAGA Place your feet on the side to give you leverage. Together, they pull the net up and into the canoe to release a wave of fish onto themselves. CHAGA Ha Ha!! Do you see this my son?! Good, good, very good! Mother will be pleased. Yes. 2. Chaga wraps Kumi in a warm hug. Kumi halfheartedly returns the embrace. EXT. ATLANTIC OCEAN - DAY Chaga paddles toward land. Kumi scans the ocean horizon through a mariner's telescope. KUMI Can we go on a trip somewhere? Maybe to visit another tribe? CHAGA We are fishermen. -

Piracy, Illicit Trade, and the Construction of Commercial

Navigating the Atlantic World: Piracy, Illicit Trade, and the Construction of Commercial Networks, 1650-1791 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Jamie LeAnne Goodall, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Margaret Newell, Advisor John Brooke David Staley Copyright by Jamie LeAnne Goodall 2016 Abstract This dissertation seeks to move pirates and their economic relationships from the social and legal margins of the Atlantic world to the center of it and integrate them into the broader history of early modern colonization and commerce. In doing so, I examine piracy and illicit activities such as smuggling and shipwrecking through a new lens. They act as a form of economic engagement that could not only be used by empires and colonies as tools of competitive international trade, but also as activities that served to fuel the developing Caribbean-Atlantic economy, in many ways allowing the plantation economy of several Caribbean-Atlantic islands to flourish. Ultimately, in places like Jamaica and Barbados, the success of the plantation economy would eventually displace the opportunistic market of piracy and related activities. Plantations rarely eradicated these economies of opportunity, though, as these islands still served as important commercial hubs: ports loaded, unloaded, and repaired ships, taverns attracted a variety of visitors, and shipwrecking became a regulated form of employment. In places like Tortuga and the Bahamas where agricultural production was not as successful, illicit activities managed to maintain a foothold much longer. -

Making a Digital Critical Edition of Captain Charles

Digitizing the Pyrates: Making a Digital Critical Edition of Captain Charles Johnson’s A General History of the Pyrates (1724-1726) by Ingrid Reiche A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Collaborative Program in the Digital Humanities and English Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2016, Ingrid Reiche Reiche ii Abstract Critical editing in a digital environment has changed how bibliographic practices are employed. This thesis investigates how digital critical editing impacts eighteenth- century literary studies. The way scholars examine questions of author attribution and employ bibliography practices has changed with the advent of digital tools. Since the mid nineteen-nineties, digital editing has taken on various forms, from hypermedia archives to crowdsourced projects. A critical apparatus that provides a high-level of interactivity to elucidate the intricacies of a text over its production in a given time is often overlooked in these projects. By producing a digital edition that compares the first four editions of A General History of the Pyrates (1724-26) using the Versioning Machine V.4.0 and conducting a user experience survey regarding the edition’s functionality (both are at http://ingridreiche.com/Resume/Thesis.html), the goal of this project has been to show how eighteenth-century print culture was a highly collaborative space where authorship was unstable. Reiche iii Acknowledgments Dedicated to Eric and Mary Ann Reiche for all their encouragement, support, hours of reading and helping to iron out my ideas. With special thanks to Professor Brian Greenspan for his editorial diligence, insight and patience, and for motivating me to always look beyond my original goals. -

Adobe PDF File

BOOK REVIEWS David M. Williams and Andrew P. White as well as those from the humanities. The (comp.). A Select Bibliography of British and section on Maritime Law lists work on Irish University Theses About Maritime pollution and the maritime environment, and History, 1792-1990. St. John's, Newfound• on the exploitation of sea resources. It is land: International Maritime Economic particularly useful to have the Open Univer• History Association, 1992. 179 pp., geo• sity and the C.NAA. theses listed. graphical and nominal indices. £10 or $20, The subjects are arranged under twenty- paper; ISBN 0-969588-5. five broad headings; there are numerous chronological geographic and subject sub• The establishment of the International and divisions and an author and geographic British Commissions for Maritime History, index to facilitate cross referencing. Though both of which have assisted in the publica• it is mildly irritating to have details some• tion of this bibliography, illustrates the times split between one column and the steadily growing interest in maritime history next, the whole book is generally convenient during the last thirty years. However, the and easy to use. The introduction explains increasing volume of research in this field the reasons for the format of the biblio• and the varied, detailed work of postgradu• graphy, its pattern of classification and the ate theses have often proved difficult to location and availability of theses. This has locate and equally difficult to consult. This recently much improved and an ASLIB bibliography provides access to this "enor• number is helpfully listed for the majority of mously rich resource" (p. -

The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse 1

The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse 1 The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Pirates' Who's Who Giving Particulars Of The Lives and Deaths Of The Pirates And Buccaneers Author: Philip Gosse Release Date: October 17, 2006 [EBook #19564] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE PIRATES' WHO'S WHO *** Produced by Suzanne Shell, Christine D. and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net Transcriber's note. Many of the names in this book (even outside quoted passages) are inconsistently spelt. I have chosen to retain the original spelling treating these as author error rather than typographical carelessness. THE PIRATES' The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse 2 WHO'S WHO Giving Particulars of the Lives & Deaths of the Pirates & Buccaneers BY PHILIP GOSSE ILLUSTRATED BURT FRANKLIN: RESEARCH & SOURCE WORKS SERIES 119 Essays in History, Economics & Social Science 51 BURT FRANKLIN NEW YORK Published by BURT FRANKLIN 235 East 44th St., New York 10017 Originally Published: 1924 Printed in the U.S.A. Library of Congress Catalog Card No.: 68-56594 Burt Franklin: Research & Source Works Series 119 Essays in History, Economics & Social Science -

When We Now Think of a Pirate's Flag We Think Of

Pirates with Ely Museum Pirate Flags When we now think of a pirate's flag we think of the "Skull and Cross Bones", however many pirates had their own unique designs that in their day would have been well known and would strike fear in the crew of a merchant ship if they saw it. To start with, many pirate ships did not have flags with designs on, instead they used different colour flags to say different things. A plain black flag had been used in the past to show a ship had plague on it and to stay away, so pirates started flying this to cause fear. However it also usually meant that the pirate would accept surrender and spare lives. Others used plain red flags, which dated back to English privateers who used it to show they were not Royal Navy, in pirate use this flag meant no surrender was accepted and no mercy would be shown! Over time pirates started adding their own designs to these plain coloured flags, these unique flags would soon become well known as the pirates reputation increased. Favourite things for pirates to have on their flags were skull, bones or sometimes whole skeletons, all meaning death and aiming to cause fear. They also often used images of swords, daggers and other weapons to show that they were ready to fight. An hourglass would mean that your time is running out as death was coming and a heart was used to show life and death. Jolly Roger Flag A flag would often be made up of one or more of those items and would sometimes include the Captain's initials or a simple outline of a figure depicting the Captain. -

The Newgate Calendar Supplement 3 Edited by Donal Ó Danachair

The Newgate Calendar Supplement 3 Edited By Donal Ó Danachair Published by the Ex-classics Project, year http://www.exclassics.com Public Domain The Newgate Calendar CONTENTS SIR HENRY MORGAN. Pirate who became Governor of Jamaica (1688) ................ 4 MAJOR STEDE BONNET. Wealthy Landowner turned Pirate, Hanged 10th December 1718 ............................................................................................................ 13 ANN HOLLAND Wife of a highwayman with whom she robbed many people. Executed 1705 .............................................................................................................. 15 DICK MORRIS. Cunning and audacious swindler, executed 1706 ........................... 16 WILLIAM NEVISON Highwayman who robbed his fellows. Executed at York, 4th May 1684 ..................................................................................................................... 19 CAPTAIN AVERY Pirate who died penniless, having been robbed of his booty by merchants ..................................................................................................................... 24 CAPTAIN MARTEL Pirate ........................................................................................ 31 CAPTAIN TEACH alias BLACK BEARD, the Most Famous Pirate of all. ............... 33 CAPTAIN EDWARD ENGLAND Pirate .................................................................. 39 CAPTAIN CHARLES VANE. Pirate ......................................................................... 49 CAPTAIN JOHN RACKAM. -

Theodore Levitt's

Quelch.ffirs 4/5/04 4:54 PM Page iii The Global Market Developing a Strategy to Manage Across Borders John Quelch Rohit Deshpande Editors Quelch.ffirs 4/5/04 4:54 PM Page ii Quelch.ffirs 4/5/04 4:54 PM Page i Quelch.ffirs 4/5/04 4:54 PM Page ii Quelch.ffirs 4/5/04 4:54 PM Page iii The Global Market Developing a Strategy to Manage Across Borders John Quelch Rohit Deshpande Editors Quelch.ffirs 4/5/04 4:54 PM Page iv Copyright © 2004 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved. Published by Jossey-Bass A Wiley Imprint 989 Market Street, San Francisco, CA 94103-1741 www.josseybass.com No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400, fax 978-750-4470, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, 201-748-6011, fax 201-748-6008, e-mail: [email protected]. Jossey-Bass books and products are available through most bookstores. To contact Jossey-Bass directly call our Customer Care Department within the U.S. -

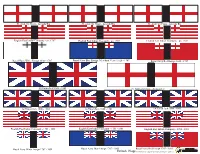

British Flags Permission to Copy for Personal Gaming Use Granted GAME STUDIOS

St AndrewsSt. Andrews Cross – CrossEnglish - Armada fl ag of the Era Armada Era St AndrewsSt. Andrews Cross – Cross English - Armada fl ag of the Era Armada Era St AndrewsSt. Andrews Cross – EnglishCross - flArmada ag of the Era Armada Era EnglishEnglish East IndianIndia Company Company - -pre pre 1707 1707 EnglishEnglish East East Indian India Company - pre 1707 EnglishEnglish EastEast IndianIndia Company Company - - pre pre 1707 1707 Standard Royal Navy Blue Squadron Ensign, Royal Navy White Ensign 1630 - 1707 Royal Navy Blue Ensign /Merchant Vessel 1620 - 1707 RoyalRoyal Navy Navy Red Red Ensign Ensign 1620 1620 - 1707 - 1707 1st Union Jack 1606 - 1801 St. Andrews Cross - Armada Era 1st1st UnionUnion fl Jackag, 1606 1606 - -1801 1801 1st1st Union Union Jack fl ag, 1606 1606 - 1801- 1801 1st1st Union Union fl Jackag, 1606 1606 - -1801 1801 English East Indian Company - 1701 - 1801 English East Indian Company - 1701 - 1801 English East Indian Company - 1701 - 1801 Royal Navy White Ensign 1707 - 1801 Royal Navy Blue Ensign 1707 - 1801 RoyalRed Navy Ensign Red as Ensignused by 1707 Royal - 1801Navy and ColonialSEA subjects DOG GAME STUDIOS British Flags Permission to copy for personal gaming use granted GAME STUDIOS . Dutch East India company fl ag Dutch East India company fl ag Dutch East India company fl ag Netherlands fl ag Netherlands fl ag Netherlands fl ag Netherlands Naval Jack Netherlands Naval Jack Netherlands Naval Jack Dutch East India company fl ag Dutch East India company fl ag Dutch East India company fl ag Netherlands fl ag Netherlands fl ag Netherlands fl ag SEA DOG Dutch Flags GAME STUDIOS Permission to copy for personal gaming use granted. -

Going on the Account: Examining Golden Age Pirates As a Distinct

GOING ON THE ACCOUNT: EXAMINING GOLDEN AGE PIRATES AS A DISTINCT CULTURE THROUGH ARTIFACT PATTERNING by Courtney E. Page December, 2014 Director of Thesis: Dr. Charles R. Ewen Major Department: Anthropology Pirates of the Golden Age (1650-1726) have become the stuff of legend. The way they looked and acted has been variously recorded through the centuries, slowly morphing them into the pirates of today’s fiction. Yet, many of the behaviors that create these images do not preserve in the archaeological environment and are just not good indicators of a pirate. Piracy is an illegal act and as a physical activity, does not survive directly in the archaeological record, making it difficult to study pirates as a distinct maritime culture. This thesis examines the use of artifact patterning to illuminate behavioral differences between pirates and other sailors. A framework for a model reflecting the patterns of artifacts found on pirate shipwrecks is presented. Artifacts from two early eighteenth century British pirate wrecks, Queen Anne’s Revenge (1718) and Whydah (1717) were categorized into five groups reflecting behavior onboard the ship, and frequencies for each group within each assemblage were obtained. The same was done for a British Naval vessel, HMS Invincible (1758), and a merchant vessel, the slaver Henrietta Marie (1699) for comparative purposes. There are not enough data at this time to predict a “pirate pattern” for identifying pirates archaeologically, and many uncontrollable factors negatively impact the data that are available, making a study of artifact frequencies difficult. This research does, however, help to reveal avenues of further study for describing this intriguing sub-culture. -

Pirates and Buccaneers of the Atlantic Coast

ITIG CC \ ',:•:. P ROV Please handle this volume with care. The University of Connecticut Libraries, Storrs Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from Lyrasis Members and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/piratesbuccaneerOOsnow PIRATES AND BUCCANEERS OF THE ATLANTIC COAST BY EDWARD ROWE SNOW AUTHOR OF The Islands of Boston Harbor; The Story of Minofs Light; Storms and Shipwrecks of New England; Romance of Boston Bay THE YANKEE PUBLISHING COMPANY 72 Broad Street Boston, Massachusetts Copyright, 1944 By Edward Rowe Snow No part of this book may be used or quoted without the written permission of the author. FIRST EDITION DECEMBER 1944 Boston Printing Company boston, massachusetts PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA IN MEMORY OF MY GRANDFATHER CAPTAIN JOSHUA NICKERSON ROWE WHO FOUGHT PIRATES WHILE ON THE CLIPPER SHIP CRYSTAL PALACE PREFACE Reader—here is a volume devoted exclusively to the buccaneers and pirates who infested the shores, bays, and islands of the Atlantic Coast of North America. This is no collection of Old Wives' Tales, half-myth, half-truth, handed down from year to year with the story more distorted with each telling, nor is it a work of fiction. This book is an accurate account of the most outstanding pirates who ever visited the shores of the Atlantic Coast. These are stories of stark realism. None of the arti- ficial school of sheltered existence is included. Except for the extreme profanity, blasphemy, and obscenity in which most pirates were adept, everything has been included which is essential for the reader to get a true and fair picture of the life of a sea-rover.