Issue: Shopping Malls Shopping Malls

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Landover Alternative

6.0 Landover Alternative Chapter 6 describes existing conditions of the Figure 6- 1: Landover Conceptual Site Plan affected environment and identifies the environmental consequences associated with the consolidation of the FBI HQ at the Landover site. A detailed description of ¨¦§495 the methodologies employed to evaluate impacts for BRIGHTSEAT ROAD ¨¦§95 each resource and the relevant regulatory framework is given in chapter 3, Methodology. The Landover site consists of approximately 80 acres of vacant land located near the intersection of Brightseat Road and Landover Road in Prince George’s County, Maryland. It is bound on the north by Evarts Street, on the east by the Capital Beltway, on the south by Landover Road, and on the west by TRUCK & EVARTS STREET SECONDARY Brightseat Road. Previously, the site was home to the TRUCK VEHICULAR SCREENING GATE Landover Mall, which operated between 1972 and REMOTE DELIVERY 2002. As of December 2014, all facilities associated FACILITY with Landover Mall have been demolished, and only STANDBY SUBSTATION GENERATORS the surface parking lot and retaining walls remain MAIN LANDOVER ROAD VEHICULAR GATE CENTRAL UTILITY WOODMORE TOWNE CENTRE on-site. Commercial uses in proximity to the site (EXIT ONLY) PLANT MAPLE RIDGE include Woodmore Towne Centre, located across the EMPLOYEE Capital Beltway (Interstate [I]-95) to the east, and the APARTMENTS PARKING Arena Plaza Shopping Center. South of Landover VISITOR CENTER Road. West of the site along Brightseat Road is the VISITOR PARKING 202 Maple Ridge apartment complex, while H.P. Johnson Park, additional apartment and single-family residential communities are located north of the site. -

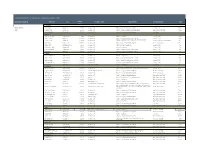

Track Record of Prior Experience of the Senior Cobalt Team

Track Record of Prior Experience of the Senior Cobalt Team Dedicated Executives PROPERTY City Square Property Type Responsibility Company/Client Term Feet COLORADO Richard Taylor Aurora Mall Aurora, CO 1,250,000 Suburban Mall Property Management - New Development DeBartolo Corp 7 Years CEO Westland Center Denver, CO 850,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and $30 million Disposition May Centers/ Centermark 9 Years North Valley Mall Denver, CO 700,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and Redevelopment First Union 3 Years FLORIDA Tyrone Square Mall St Petersburg, FL 1,180,000 Suburban Mall Property Management DeBartolo Corp 3 Years University Mall Tampa, FL 1,300,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and New Development DeBartolo Corp 2 Years Property Management, Asset Management, New Development Altamonte Mall Orlando, FL 1,200,000 Suburban Mall DeBartolo Corp and O'Connor Group 1 Year and $125 million Disposition Edison Mall Ft Meyers, FL 1,000,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and Redevelopment The O'Connor Group 9 Years Volusia Mall Daytona Beach ,FL 950,000 Suburban Mall Property and Asset Management DeBartolo Corp 1 Year DeSoto Square Mall Bradenton, FL 850,000 Suburban Mall Property Management DeBartolo Corp 1 Year Pinellas Square Mall St Petersburg, FL 800,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and New Development DeBartolo Corp 1 Year EastLake Mall Tampa, FL 850,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and New Development DeBartolo Corp 1 Year INDIANA Lafayette Square Mall Indianapolis, IN 1,100,000 Suburban Mall Property Management -

STATE of MICHIGAN CIRCUIT COURT for the 6TH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT OAKLAND COUNTY SIMON PROPERTY GROUP, INC. and SIMON PROPERTY GROUP

STATE OF MICHIGAN CIRCUIT COURT FOR THE 6TH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT OAKLAND COUNTY SIMON PROPERTY GROUP, INC. and SIMON PROPERTY GROUP, L.P., Plaintiffs, Case No. v. TAUBMAN CENTERS, INC. and TAUBMAN REALTY GROUP, L.P., Honorable Defendants. There is no other pending or resolved civil action arising out of the transaction or occurrence alleged in this complaint. This case involves a business or commercial dispute as defined in MCL 600.8031 and meets the statutory requirements to be assigned to the business court. COMPLAINT Plaintiffs Simon Property Group, Inc. (“SPG”) and Simon Property Group L.P. (“SPG Operating Partnership”) (collectively “Simon”), by and through their undersigned counsel, file this Complaint against Defendants Taubman Centers, Inc. (“TCO”) and Taubman Realty Group, L.P. (“TRG”) (collectively, “Taubman” or “Defendants”), upon knowledge as to matters relating to themselves and upon information and belief as to all other matters, and allege as follows: NATURE OF THE CLAIMS 1. On February 9, 2020, after extensive negotiations, Simon agreed to acquire most of Taubman—a retail real estate company that promotes itself as having the “most productive” shopping centers in the United States—for approximately $3.6 billion. Taubman agreed that Simon could terminate the deal if Taubman suffered a Material Adverse Effect Document Submitted for Filing to MI Oakland County 6th Circuit Court. (“MAE”) or if Taubman breached its covenant to operate its business in the ordinary course until closing. The parties explicitly agreed that a “pandemic” would be an MAE, if it disproportionately affected Taubman “as compared to other participants in the industries in which [it] operate[s].” On June 10, 2020, Simon properly exercised its right to terminate the acquisition agreement (the “Agreement”; Ex. -

Urban Suburban: Re-Defining the Suburban Shopping Centre and the Search for a Sense of Place

Urban Suburban: Re-Defining the Suburban Shopping Centre and the Search for a Sense of Place By Trevor D. Schram A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2014, Trevor D. Schram 2 Abstract In today’s suburban condition, the shopping centre has become a significant destination for many. Vastly sized, it has become a cultural landmark within many suburban and urban neighbourhoods. Not only a space for ‘purchasing’, the suburban shopping centre has become a place to shop, a place to eat, a place to meet, a place to exercise – a social space. However, with the development and conception of a big box environment and a new typology of consumerism (and architecture) at play, the ‘suburban shopping mall’ as we currently know it, is slowly disappearing. Consumerism has always been an important aspect of many cities within the Western World, and more recently it is understood as a cultural phenomenon1. Early department stores have been, and are, architecturally and culturally significant, having engaged people through such devices as store windows and a ‘grand’ sense of place. It is more recently that shopping centres have become a space for the suburban community to engage – a social space to shop, eat and purchase. Suburban malls, which were once successful in serving their suburban communities, are on the decline. These malls are suffering financially as 1 Hudson’s Bay Company Heritage: The Department Store. Hudson’s Bay Company. Accessed online <http://www.hbcheritage.ca/hbcheritage/history/social> 3 stores close and the community no longer has reason to attend these dying monoliths – it is with this catalyst that the mall eventually has no choice but to close. -

Two-Year Appraisal Services Contracts to Terzo Bologna, Integra Realty

CITY of NOVI CITY COUNCIL Agenda Item 8 May 20,2013 cityofnovi.org SUBJECT: Approval to award two (2) year appraisal services contracts to Terzo Bologna Inc., Integra Realty Resources, and fuller Appraisal Services to provide Property Appraisal and Related Services, for an estimated annual amount of $135,000. • I SUBMITTING DEPARTMENT: A,,es~mg ,~/'/ CITY MANAGER APPRO¢: I EXPENDITURE REQUIRED $135,000 Estimated AMOUNT BUDGETED $135,000 2013-2014 and $135,000 2104-2015 APPROPRIATION REQUIRED $0 LINE ITEM NUMBER 101-209.00-816.900 BACKGROUND INFORMATION: The City periodically requires professional property appraisals and expert testimony on commercial, industrial and residential properties that are being appealed to the Michigan Tax Tribunal. A Request for Qualifications (RFQ) was posted in March 2013 on the MITN/Bidnet website and three (3) responses were received. All three responders are currently providing appraisal services to the City of Novi. The most recent RFQs were evaluated for their personnel qualifications and their expertise in the areas of commercial, industrial, residential, and personal property appraisals. The three firms listed above are in good standing and have assisted the Assessing Department in the resolution of many cases. Two one (1) year options will be available to the city at the end of two (2) year contract. For each Michigan Tax Tribunal case requiring an appraisal, the firms will be reviewed for subject expertise and contacted for competitive quotes when appropriate. All quotes provided for appraisals will be lump sum for the complete appraisal. Typically, an appraisal will cost between $5,000 and $15,000 depending on property type and complexity. -

Latinos | Creating Shopping Centers to Meet Their Needs May 23, 2014 by Anthony Pingicer

Latinos | Creating shopping centers to meet their needs May 23, 2014 by Anthony Pingicer Source: DealMakers.net One in every six Americans is Latino. Since 1980, the Latino population in the United States has increased dramatically from 14.6 million, per the Census Bureau, to exceeding 50 million today. This escalation is not just seen in major metropolitan cities and along the America-Mexico border, but throughout the country, from Cook County, Illinois to Miami-Dade, Florida. By 2050, the Latino population is projected to reach 134.8 million, resulting in a 30.2 percent share of the U.S. population. Latinos are key players in the nation’s economy. While the present economy benefits from Latinos, the future of the U.S. economy is most likely to depend on the Latino market, according to “State of the Hispanic Consumer: The Hispanic Market Imperative,” a report released by Nielsen, an advertising and global marketing research company. According to the report, the Latino buying power of $1 trillion in 2010 is predicted to see a 50 percent increase by next year, reaching close to $1.5 trillion in 2015. The U.S. Latino market is one of the top 10 economies in the world and Latino households in America that earn $50,000 or more are growing at a faster rate than total U.S. households. As for consumption trends, Latinos tend to spend more money per shopping trip and are also expected to become a powerful force in home purchasing during the next decade. Business is booming for Latinos. According to a study by the Partnership for a New Economy, the number of U.S. -

Pedestrian Malls

Pedestrian Malls Downtown Madison, Inc. JANUARY 20, 2021 | MADISON, WI i Pedestrian Malls Table of Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................... 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 2 PART I: Pedestrian Malls ........................................................................................................ 2 BACKGROUND ...............................................................................................................................3 Early Pedestrian Zones ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Coming to America (1945-Present) ...................................................................................................................... 4 Suburban Shift (1950-1975) ................................................................................................................................. 5 Rise and Fall of Competing Mall Designs ................................................................................ 6 Decline of Pedestrian Malls (1980-1990) ............................................................................................................. 6 Decline of Suburban Shopping Malls (2000-2020) ............................................................................................... 7 Modern Pedestrian -

Taubman Centers, Inc. Annual Meeting Investor Presentation

Taubman Centers, Inc. Annual Meeting Investor Presentation Spring 2018 0 We are Taubman We own, manage and develop retail properties that deliver superior financial performance to our shareholders 23 Owned Centers¹ We distinguish ourselves by creating extraordinary retail properties where customers choose to shop, dine and be entertained; where retailers can thrive $10.7bn Total Market Cap² As we benefit from the markets in which we operate, we endeavor to give back and ensure our presence adds value to our employees, our tenants and communities $12.5bn Est. Gross Asset Value³ We foster a rewarding and empowering work environment, where we strive for excellence, encourage innovation and demonstrate teamwork 68 We recognize that strong governance improves corporate decision-making and Years in strengthens our company, and we have taken steps to significantly enhance Operation our governance We have been the best performing U.S. public mall REIT over the last 20 years 468 with a 14% total shareholder return CAGR and have grown our sales per square Employees4 foot by ~18% over the past five years5 Source: Company filings as of 31-Dec-2017 (1) Includes centers from unconsolidated JVs, as of 1-May-2018. (2) As of 31-Dec-2017. (3) Per Green Street Advisors. (4) Full-time employees as of 31-Dec-2017, including Taubman Asia and certain other affiliates. (5) TSR per KeyBanc Capital Markets: The Leaderboard; sales per square foot growth reflects the increase from 2012 ($688) to 2017 ($810). 1 Key Accomplishments Through 2017 Both our recent and historical performance reflect our ability to create long-term sustainable value 14.0% 4.5 % $810 20-Year Total Shareholder Dividend CAGR Highest Sales Per Square 1 2 Return CAGR Since IPO Foot in the U.S. -

LARGEST RETAIL Centersranked by Gross Leasable Area

CRAIN'S LIST: LARGEST RETAIL CENTERS Ranked by gross leasable area Shopping center name Leasing agent Address Gross leasable area Company Number of Rank Phone; website Top executive(s) (square footage) Center type Phone stores Anchors Lakeside Mall Ed Kubes 1,550,450 Super-regional Rob Michaels 180 Macy's, Macy's Men & Home, Sears, JCPenney, Lord 14000 Lakeside Circle, Sterling Heights 48313 general manager General Growth Properties Inc. & Taylor 1. (586) 247-1590; www.shop-lakesidemall.com (312) 960-5270 Twelve Oaks Mall Daniel Jones 1,513,000 Super-regional Margaux Levy-Keusch 200 Nordstrom, Macy's, Lord & Taylor, JCPenney, Sears 27500 Novi Road, Novi 48377 general manager The Taubman Co. 2. (248) 348-9400; www.shoptwelveoaks.com (248) 258-6800 Oakland Mall Peter Light 1,500,000 Super-regional Jennifer Jones 127 Macy's, Sears, JCPenney 412 W. 14 Mile Road, Troy 48083 general manager Urban Retail Properties LLC 3. (248) 585-6000; www.oaklandmall.com (248) 585-4114 Northland Center Brent Reetz 1,464,434 Super-regional Amanda Royalty 122 Macy's, Target 21500 Northwestern Hwy., Southfield 48075 general manager AAC Realty 4. (248) 569-6272; www.shopatnorthland.com (317) 590-7913 Somerset Collection John Myszak 1,440,000 Super-regional The Forbes Co. 180 Macy's, Neiman Marcus, Nordstrom, Saks Fifth 2800 W. Big Beaver Road, Troy 48084 general manager (248) 827-4600 Avenue 5. (248) 643-6360; www.thesomersetcollection.com Eastland Center Brent Reetz 1,393,222 Super-regional Casey Conley 105 Target, Macy's, Lowe's, Burlington Coat Factory, 18000 Vernier Road, Harper Woods 48225 general manager (313) 371-1500 K & G Fashions 6. -

Preliminary Design of Bus Rapid Transit in the Southfield/Jefferies C

GM Tlansportation Systems 4.0 INTERMEDIATE SERVICE IN THE SOUTHFIELD-GREENFIELD CORRIDOR The potential transit demand in the Southfield-Greenfield corridor, as estimated in Stage I, is not sufficient to support the non-stop (or one-stop) BRT service envisioned for the Southfield-Jeffries corridor, An intermediate stopping service is therefore proposed to provide improved transit service in the corridor, This section of the final report presents the analyses which led to the design of the Intermediate Service, Following an over view of the system, the evaluation of alternative routes and implementations is described. Then a summary of the corridor demand analysis, including consideration of potential demand for Fairlane, is presented, Finally, system cost estimates are presented. 4.1 Overview of Greenfield Intermediate Service The objective of the Intermediate Service is to provide a higher level of service in the Southfield-Greenfield corridor than is currently being provided by local buses with a system that can be deployed quiGkly and with low capital investment. The system which is proposed to satisfy this objective is an intermediate level bus service operating on Greenfield Road between Southfield and Dearborn, The system is designed to provide improved travel time for relatively long transit trips (two miles or more) by stopping only at major cross-streets and by operating with traffic signal pre-emption. The proposed system operates at constant 12-minute headway throughout the day from 7:00a.m. to 9:00p.m. During periods of peak work trip demand (7:00 to 10:00 a.m. and 3:00 to 6:00p.m.), the route is configured so that direct distribution service is provided to employment sites in Dearborn and in Southfield along Northwestern Highway. -

The Afterlife of Malls

The Afterlife of Malls John Drain INTRODUCTION teenage embarrassments and rejection, along with fonder It seems like it was yesterday: Grandpa imagined the search memories – from visiting Mall Santa to getting fitted for my for some new music would distract him from an illness prom tux. that was reaching its terminal stage. This meant a trip to the Rolling Acres Mall at Akron’s western fringe; probably Some spectators interpret the decline of malls as a signal the destination was a Sam Goody, which in 1996 was as that auto-oriented suburban sprawl is finally unwinding. synonymous with record store as iTunes is with music today. Iconoclasts might attribute their abrupt collapse to a Grandpa bought a couple tapes and then happily strolled conspiracy of “planned obsolescence,” or even declare this the mall concourse. But his relief quickly faded; he slowed a symptom of a decadent society. Some will fault today’s his clip and sidled into a composite bench-planter on a politics or the Great Recession (anachronistically, in most carpeted oasis, confessing, “I am so tired.” cases). Some attribute the decline to a compromised sense of safety among crowds of people who aren’t exposed Grandpa and his cohort – the rubber workers – have mostly to an intensive security screening (certainly the violent vanished from Akron. The Rolling Acres Mall is abandoned. incidents in Ward Parkway Mall in Kansas City2 or the City The so-called “shadow retail” that gradually built up around Center in Columbus3 lend some credence to this view that the mall is today the shadow of a ghost. -

Presentazione Di Powerpoint

corso di laurea UPTA / aa. 2017-2018 / corso_zero_la_città_che_cambia / prof. Daniela Lepore I LUOGHI DEL COMMERCIO Dal mercato al mall (già in crisi) passando per il supermercato info e credit foto E’ IL MERCATO CHE FA LA CITTÀ Altra caratteristica che deve coesistere perché si possa parlare di “città” è l'esistenza di uno scambio regolare e non solo occasionale di merci sul luogo dell'insediamento quale elemento essenziale del guadagno e dell'approvvigionamento degli abitanti: cioè l'esistenza del mercato. Però non tutti i “mercati” fanno dell'abitato, in cui hanno luogo, una “città”. Le fiere periodiche ed i mercati … nei quali s'incontrano a data fissa commercianti che vi convengono per vendere le loro merci all'ingrosso e al minuto fra loro od ai consumatori, avevano spesso la loro sede in luoghi che noi chiamiamo “villaggi”. Noi vogliamo parlare di “città” nel senso economico solo nei casi in cui la popolazione stabile copre una parte economicamente essenziale del suo fabbisogno giornaliero sul mercato locale ed in particolare prevalentemente con prodotti che la popolazione locale e quella degli immediati dintorni ha fabbricato oppure acquistato per la vendita sul mercato. Ogni città nel senso qui usato è “luogo di mercato”, ossia possiede un mercato locale quale centro economico dell'insediamento, sul quale, in seguito all'esistente specializzazione della produzione economica, anche la popolazione non cittadina copre il suo fabbisogno di prodotti industriali o di articoli commerciali o di entrambi contemporaneamente e sul quale naturalmente anche i cittadini stessi scambiano fra loro le specialità ed i prodotti occorrenti per il consumo delle loro aziende.