Pedestrian Malls

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

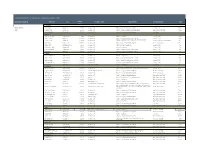

Track Record of Prior Experience of the Senior Cobalt Team

Track Record of Prior Experience of the Senior Cobalt Team Dedicated Executives PROPERTY City Square Property Type Responsibility Company/Client Term Feet COLORADO Richard Taylor Aurora Mall Aurora, CO 1,250,000 Suburban Mall Property Management - New Development DeBartolo Corp 7 Years CEO Westland Center Denver, CO 850,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and $30 million Disposition May Centers/ Centermark 9 Years North Valley Mall Denver, CO 700,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and Redevelopment First Union 3 Years FLORIDA Tyrone Square Mall St Petersburg, FL 1,180,000 Suburban Mall Property Management DeBartolo Corp 3 Years University Mall Tampa, FL 1,300,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and New Development DeBartolo Corp 2 Years Property Management, Asset Management, New Development Altamonte Mall Orlando, FL 1,200,000 Suburban Mall DeBartolo Corp and O'Connor Group 1 Year and $125 million Disposition Edison Mall Ft Meyers, FL 1,000,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and Redevelopment The O'Connor Group 9 Years Volusia Mall Daytona Beach ,FL 950,000 Suburban Mall Property and Asset Management DeBartolo Corp 1 Year DeSoto Square Mall Bradenton, FL 850,000 Suburban Mall Property Management DeBartolo Corp 1 Year Pinellas Square Mall St Petersburg, FL 800,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and New Development DeBartolo Corp 1 Year EastLake Mall Tampa, FL 850,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and New Development DeBartolo Corp 1 Year INDIANA Lafayette Square Mall Indianapolis, IN 1,100,000 Suburban Mall Property Management -

Issue: Shopping Malls Shopping Malls

Issue: Shopping Malls Shopping Malls By: Sharon O’Malley Pub. Date: August 29, 2016 Access Date: October 1, 2021 DOI: 10.1177/237455680217.n1 Source URL: http://businessresearcher.sagepub.com/sbr-1775-100682-2747282/20160829/shopping-malls ©2021 SAGE Publishing, Inc. All Rights Reserved. ©2021 SAGE Publishing, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Can they survive in the 21st century? Executive Summary For one analyst, the opening of a new enclosed mall is akin to watching a dinosaur traversing the landscape: It’s something not seen anymore. Dozens of malls have closed since 2011, and one study predicts at least 15 percent of the country’s largest 1,052 malls could cease operations over the next decade. Retail analysts say threats to the mall range from the rise of e-commerce to the demise of the “anchor” department store. What’s more, traditional malls do not hold the same allure for today’s teens as they did for Baby Boomers in the 1960s and ’70s. For malls to remain relevant, developers are repositioning them into must-visit destinations that feature not only shopping but also attractions such as amusement parks or trendy restaurants. Many are experimenting with open-air town centers that create the feel of an urban experience by positioning upscale retailers alongside apartments, offices, parks and restaurants. Among the questions under debate: Can the traditional shopping mall survive? Is e-commerce killing the shopping mall? Do mall closures hurt the economy? Overview Minnesota’s Mall of America, largest in the U.S., includes a theme park, wedding chapel and other nonretail attractions in an attempt to draw patrons. -

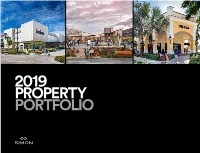

2019 Property Portfolio Simon Malls®

The Shops at Clearfork Denver Premium Outlets® The Colonnade Outlets at Sawgrass Mills® 2019 PROPERTY PORTFOLIO SIMON MALLS® LOCATION GLA IN SQ. FT. MAJOR RETAILERS CONTACTS PROPERTY NAME 2 THE SIMON EXPERIENCE WHERE BRANDS & COMMUNITIES COME TOGETHER SIMON MALLS® LOCATION GLA IN SQ. FT. MAJOR RETAILERS CONTACTS PROPERTY NAME 2 ABOUT SIMON Simon® is a global leader in retail real estate ownership, management, and development and an S&P 100 company (Simon Property Group, NYSE:SPG). Our industry-leading retail properties and investments across North America, Europe, and Asia provide shopping experiences for millions of consumers every day and generate billions in annual sales. For more information, visit simon.com. · Information as of 12/16/2019 3 SIMON MALLS® LOCATION GLA IN SQ. FT. MAJOR RETAILERS CONTACTS PROPERTY NAME More than real estate, we are a company of experiences. For our guests, we provide distinctive shopping, dining, and entertainment. For our retailers, we offer the unique opportunity to thrive in the best retail real estate in the best markets. From new projects and redevelopments to acquisitions and mergers, we are continuously evaluating our portfolio to enhance the Simon experience—places where people choose to shop and retailers want to be. 4 LOCATION GLA IN SQ. FT. MAJOR RETAILERS CONTACTS PROPERTY NAME WE DELIVER: SCALE A global leader in the ownership of premier shopping, dining, entertainment, and mixed-use destinations, including Simon Malls®, Simon Premium Outlets®, and The Mills® QUALITY Iconic, irreplaceable properties in great locations INVESTMENT Active portfolio management increases productivity and returns GROWTH Core business and strategic acquisitions drive performance EXPERIENCE Decades of expertise in development, ownership, and management That’s the advantage of leasing with Simon. -

Ticketmaster and Simon Property Group Bring Tickets to Shopping Malls Across the Country

TICKETMASTER AND SIMON PROPERTY GROUP BRING TICKETS TO SHOPPING MALLS ACROSS THE COUNTRY - Ticketmaster Tickets Now Available at More Than 70 Simon Mall Locations Nationwide - LOS ANGELES – November 2, 2011 – Ticketmaster, a Live Nation Entertainment company (NYSE:LYV), and Simon Property Group, Inc. (NYSE:SPG), the country's largest owner, developer and manager of high quality retail real estate have extended and expanded their unique relationship, opening twenty-two additional Ticketmaster ticket purchasing locations in Simon malls, for a total of seventy-two Simon Malls now offering Ticketmaster event tickets at Guest Services. “Ticketmaster’s retail outlets at our Guest Service locations have been a convenient amenity for millions of our shoppers. We are pleased to be extending and expanding our relationship with Ticketmaster,” said Dennis Tietjen, senior vice president of Simon Brand Ventures, a division of Simon Property Group. “Recognizing the strategic value of Simon as a distribution channel, we worked together, to deliver a solution that would raise awareness of events and provide an onsite ticket purchasing option for our fans in their neighborhood shopping mall,” said Sandy Gaare, executive vice president of retail partners, Ticketmaster. “Ticketmaster is committed to providing convenient ticket purchasing options through our online store and our thousands of retail outlets.” In each of the seventy-two participating Simon malls, fans may purchase tickets at the Guest Service desk from a Simon associate. Tickets are printed on traditional ticket stock and are produced on location. Ticketmaster Retail Centers in Simon Malls: Apple Blossom Mall (Winchester, VA) Coral Square (Coral Springs, FL) Arsenal Mall® (Watertown, MA) Crystal Mall (Waterford, CT) Arundel Mills (Hanover, MD) Dadeland Mall (Miami, FL) Auburn Mall (Auburn, MA) DeSoto Square (Bradenton, FL) Battlefield Mall (Springfield, MO) Edison Mall (Ft. -

Store # State City Mall/Shopping Center Name Address Date 2918

Store # State City Mall/Shopping Center Name Address Date 2918 AL ALABASTER COLONIAL PROMENADE 340 S COLONIAL DR Coming Soon in September 2016! 2218 AL HOOVER RIVERCHASE GALLERIA 2300 RIVERCHASE GALLERIA Coming Soon in September 2016! 2131 AL HUNTSVILLE MADISON SQUARE 5901 UNIVERSITY DR Coming Soon in September 2016! 219 AL MOBILE BEL AIR MALL MOBILE, AL 36606-3411 Coming Soon in September 2016! 2840 AL MONTGOMERY EASTDALE MALL MONTGOMERY, AL 36117-2154 Coming Soon in September 2016! 2956 AL PRATTVILLE HIGH POINT TOWN CENTER PRATTVILLE, AL 36066-6542 Coming Soon in September 2016! 2875 AL SPANISH FORT SPANISH FORT TOWN CENTER 22500 TOWN CENTER AVE Coming Soon in September 2016! 2869 AL TRUSSVILLE TUTWILER FARM 5060 PINNACLE SQ Coming Soon in September 2016! 2709 AR FAYETTEVILLE NW ARKANSAS MALL 4201 N SHILOH DR Coming Soon in September 2016! 1961 AR FORT SMITH CENTRAL MALL 5111 ROGERS AVE Coming Soon in September 2016! 2914 AR LITTLE ROCK SHACKLEFORD CROSSING 2600 S SHACKLEFORD RD Coming Soon in July 2016! 663 AR NORTH LITTLE ROCK MC CAIN SHOPPING CENTER 3929 MCCAIN BLVD STE 500 Coming Soon in July 2016! 2879 AR ROGERS PINNACLE HLLS PROMDE 2202 BELLVIEW RD Coming Soon in September 2016! 2936 AZ CASA GRANDE PROMNDE AT CASA GRANDE 1041 N PROMENADE PKWY Coming Soon in September 2016! 157 AZ CHANDLER MILL CROSSING 2180 S GILBERT RD Coming Soon in September 2016! 251 AZ GLENDALE ARROWHEAD TOWNE CENTER 7750 W ARROWHEAD TOWNE CENTER Coming Soon in September 2016! 2842 AZ GOODYEAR PALM VALLEY CORNERST 13333 W MCDOWELL RD Coming Soon in September -

Southdale Library Heading for Southdale Center Library Planned for Herberger’S Site

Edition: Edina JULY 2019 Strong Reliable Livable Better CITY GOALS: Foundation Service City Together Volume 6, Issue 7 Southdale Library Heading For Southdale Center Library Planned for Herberger’s Site Construction on the new Hennepin County Library – Southdale could start in 2020, with an estimated completion in early 2022. With the new library, Southdale Center moves closer to architect Victor Gruen’s vision of a community- centered facility that provides goods, services and civic amenities that are connected to surrounding residents. Hennepin County plans to build the library on a portion of the old Herberger’s site at Southdale Center, most visible from West 69th Street and York Avenue. “The new site allows us to maintain our valued core services, our access to physical materials, community responsive programming and more – really, those services that patrons have come to value at the Southdale Library for a long time, but in a new secure and welcoming space,” said Interim Library Director Janet Mills. After considering construction and operational costs, access to other services and public transportation, Hennepin County Board of Commissioners voted June 18 to negotiate a The new space will also offer a new and unique Hennepin County staff will collaborate with Simon Property Group lease for the Southdale Library at Southdale opportunity to deepen community connection on the exterior of the new building at Southdale Center and will lead design efforts for the interior spaces. Submitted Illustration Center. Patrons will be able to access the and provide innovative and inclusive programs new library from both the shopping mall and and services without a pause in service during parking lot. -

Oic / Law Enforcement Summit Overview

OPERATIONAL INTELLIGENCE CENTER LAW ENFORCEMENT SUMMIT AUGUST 25 & 26, 2019 INDIANAPOLIS, INDIANA OIC / LAW ENFORCEMENT SUMMIT OVERVIEW As part of Simon’s commitment to developing strong public/private relationships with our centers and local law enforcement, we have organized numerous conferences across the country over the past decade. For 2019, we will be hosting a two-day conference in Indianapolis, bringing together law enforcement executives, mall management teams and security directors from 73 premiere properties throughout the Simon Malls, Mills, and Premium Outlets portfolio. In addition, the FBI and DHS will also be participating in this summit as well as key security personnel from a variety of luxury retail brands. On the first evening, a series of live simulations will occur, along with a demonstration of Simon's new Operational Intelligence Center (OIC), followed by a second day of speakers from a variety of backgrounds, discussing relevant challenges facing the retail security realm. As we have in years past, we will be securing sponsors to help us underwrite this event to ensure we have strong attendance from our local law enforcement agencies, stationed all across the US. Sponsors will be encouraged to network with all participants and we will be hosting a Summit Showcase as well where participants will be able to demonstrate products, services and devices utilized at Simon malls or local law enforcement offices each day. The OIC Law Enforcement Summit will take place at The Sheraton Hotel attached to Keystone Fashion -

In the Superior Court of the State of Delaware Simon

EFiled: Jun 02 2020 05:08PM EDT Transaction ID 65668754 Case No. N20C-06-034 EMD CCLD IN THE SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF DELAWARE SIMON PROPERTY GROUP, L.P., ) on behalf of itself and its affiliated ) landlord entities, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) C.A. No. (CCLD) ) THE GAP, INC., OLD NAVY, LLC, ) INTERMIX HOLDCO, INC., ) BANANA REPUBLIC, LLC, AND ) ATHLETA LLC, ) ) Defendants. ) COMPLAINT Plaintiff Simon Property Group, L.P. (“Simon”), on behalf of itself and as assignee of its various landlord entities (“Simon Landlords”), by and through its undersigned counsel, and as for its Complaint against The Gap, Inc., Old Navy, LLC, Intermix HoldCo, Inc., Banana Republic, LLC, and Athleta LLC (collectively, “Defendants” or “The Gap Entities”), alleges and states as follows: NATURE OF THE ACTION 1. Simon seeks monetary damages from The Gap Entities for failure to pay more than $65.9 million in rent and other charges due and owing under certain retail Leases (defined below) plus attorneys’ fees and expenses incurred in connection with this suit. 2. The Gap Entities are in default on each of the Leases for failure to pay rent for April, May and June, 2020. As of the date of this filing (June 2, 2020), there is due and owing approximately $65.9 million in unpaid rent to each of the Landlord entities. The amounts due and owing will continue to accrue each month, with interest, and The Gap Entities are expected to fall even further behind in rent and other charges due to be paid to the Simon Landlords. PARTIES 3. Simon, a Delaware limited partnership, is the principal operating partnership for Simon Property Group, Inc., a publicly-held Delaware corporation and Simon’s sole general partner. -

The Cheesecake Factory Restaurants in Operation

The Cheesecake Factory® Restaurants in Operation State City Location Address Phone Alabama Birmingham The Summit 236 Summit Boulevard (205) 262-1800 Arizona Chandler Chandler Fashion Center 3111 W. Chandler Boulevard (480) 792-1300 Mesa Superstition Springs Center 6613 East Southern Avenue (480) 641-7300 Peoria Arrowhead Fountains Center 16134 N. 83rd Avenue (623) 773-2233 Phoenix Biltmore Fashion Park 2402 E. Camelback Road (602) 778-6501 Scottsdale Kierland Commons 15230 N. Scottsdale Road (480) 607-0083 Tucson Tucson Mall 60 West Wetmore Road (520) 408-0033 California Anaheim Anaheim Garden Walk 321 Katella Avenue (714) 533-7500 Beverly Hills 364 N. Beverly Drive (310) 278-7270 Brea Brea Mall 120 Brea Mall Way (714) 255-0115 Carlsbad The Shoppes at Carlsbad 2525 El Camino Real (760) 730-9880 Cerritos Los Cerritos Center 201 Los Cerritos Center (562) 402-2906 Chula Vista Otay Ranch Town Center 2015 Birch Road (619) 421-2500 Corte Madera The Village 1736 Redwood Highway (415) 945-0777 Escondido North County Mall 200 E. Via Rancho Parkway (760) 743-2253 Fresno Fashion Fair Mall 639 East Shaw Avenue (559) 228-1400 Glendale Americana at Brand 511 Americana Way (818) 550-7505 Huntington Beach Bella Terra Mall 7871 Edinger Avenue (714) 889-1500 Irvine Irvine Spectrum 71 Fortune Drive (949) 788-9998 Los Angeles The Grove 189 The Grove Drive (323) 634-0511 Marina del Rey 4142 Via Marina (310) 306-3344 Mission Viejo The Shops at Mission Viejo 42 The Shops at Mission Viejo (949) 364-6200 Newport Beach Fashion Island Mall 1141 Newport Center Drive (949) 720-8333 Oxnard The Collection at RiverPark 600 Town Center Drive (805) 278-8878 Pasadena 2 West Colorado Boulevard (626) 584-6000 Pleasanton Stoneridge Mall 1350 Stoneridge Mall Road (925) 463-1311 Rancho Cucamonga Victoria Gardens Mall 12379 N. -

Store Listing

APPENDIX C STORE LISTING All shipments must be shipped to the Dry Goods Distribution Center at with the specific store name, abbreviation or number indicated on the Shipping Label, Carton, and Packing Slip. Do not ship directly to the store. DRY GOODS - Distribution Center 6565 Brady Street Davenport, IA 52806 Store # Store Initials Store Name/Location 1001 FXVY Fox Valley/Aurora, IL 1002 WFLD Woodfield Mall/Schaumburg, IL 1003 WSTN West Towne/Madison, WI 1004 MYFR Mayfair Mall/Milwaukee, WI 1005 TWOK Twelve Oaks Mall/Detroit, MI 1006 RSDL Rosedale Mall/Roseville, MN 1007 ORSQ Orland Square/Orland Park, IL 1008 JDCR Jordan Creek Mall/West Des Moines, IA 1009 STDL Southdale Center/Edina, MN 1010 CRIA Coralridge Mall/Coralville, IA 1011 HWIL Westfield Hawthorn/Vernon Hills, IL 1012 APMN Apache Mall/Rochester, MN 1013 FMIN Fashion Mall/Indianapolis, IN 1014 CRMN Crossroads Center/St. Cloud, MN 1015 RDMN Ridgedale Center/Minnetonka, MN 1016 BRMI Briarwood Mall/Ann Arbor, MI 1017 UPIN University Park/Mishawaka, IN 1018 GRIN Greenwood Park/Greenwood, IN 1019 WDMI Woodland Mall/Grand Rapids, MI 1020 FRWI Fox River/Appleton, WI 1021 GSIN Glenbrook Square Mall, Fort Wayne, IN 1022 MPIL Market Place, Champaign, IL 1023 OBIL OakBrook Center, Oak Brook, IL 1024 OOIL Old Orchard Mall, Skokie, IL 1025 KWOH Kenwood Towne Center, Cincinnati, OH 1026 FYKY Fayette Mall, Lexington, KY 1027 SMKY Mall St. Matthews, Louisville, KY 1028* GPIL The Shoppes at Grand Prairie, Peoria, IL 1029* PFOH Polaris Fashion Place, Columbus, OH 1030* TCOH Tuttle Crossing, Columbus, OH 1031* WAND West Acres, Fargo, ND 1032** WRNE Westroads Mall, Omaha, NE 1033** CRMI Crossroads Mall, Kalamazoo, MI 1034** NPIA Northpark Mall, Davenport, IA 1035** TGOH The Greene, Dayton, OH 1036** GLMO St. -

'Rotch Sep 20 2002 Libraries

Declining Tenant Diversity in Retail Malls: 1970-2000 By Matthew M. Doelger B.A., Economics, 1998 Wheaton College Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Real Estate Development at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September, 2002 Copyright 2002 Matthew M. Doelger All rights reserved The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author Depart'ment~pfrbaqSSties and Planning August 2, 2002 Certified by_ John Riordan Thomas G. Eastman Chairman, Center for Real Estate Thesis Supervisor Accepted by William C. Wheaton Chairman, Interdepartmental Degree Program in Real Estate Development 'ROTCH MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SEP 20 2002 LIBRARIES DECLINING TENANT DIVERSITY IN RETAIL MALLS: 1970-2000 by MATTHEW M. DOELGER Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on August 2, 2002 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Real Estate Development ABSTRACT A study of tenant diversity in retail malls was carried out to determine if tenant diversity declined between 1970 and 2000. The study measured tenant diversity by examining the percent of tenants that occur more than once in a given set of sample malls where each occupant of a single mall space counts as a single tenant. The study examined three sets of malls: a five-mall set of malls located in Massachusetts, a five-mall set of nationally distributed malls owned by different/separate owners, and a five-mall set of malls owned by the largest owner of retail malls, Simon Property Group. -

The Cheesecake Factory Company-Owned

The Cheesecake Factory® Company-Owned Restaurants in Operation State City Location Address Phone Alabama Birmingham The Summit 236 Summit Boulevard (205) 262-1800 Arizona Chandler Chandler Fashion Center 3111 W. Chandler Boulevard (480) 792-1300 Mesa Superstition Springs Center 6613 East Southern Avenue (480) 641-7300 Peoria Arrowhead Fountains Center 16134 N. 83rd Avenue (623) 773-2233 Phoenix Biltmore Fashion Park 2402 E. Camelback Road (602) 778-6501 Scottsdale Kierland Commons 15230 N. Scottsdale Road (480) 607-0083 Tucson Tucson Mall 60 West Wetmore Road (520) 408-0033 California Anaheim Anaheim Garden Walk 321 Katella Avenue (714) 533-7500 Beverly Hills 364 N. Beverly Drive (310) 278-7270 Brea Brea Mall 120 Brea Mall Way (714) 255-0115 Carlsbad The Shoppes at Carlsbad 2525 El Camino Real (760) 730-9880 Cerritos Los Cerritos Center 201 Los Cerritos Center (562) 402-2906 Chula Vista Otay Ranch Town Center 2015 Birch Road (619) 421-2500 Corte Madera The Village 1736 Redwood Highway (415) 945-0777 Escondido North County Mall 200 E. Via Rancho Parkway (760) 743-2253 Fresno Fashion Fair Mall 639 East Shaw Avenue (559) 228-1400 Glendale Americana at Brand 511 Americana Way (818) 550-7505 Huntington Beach Bella Terra Mall 7871 Edinger Avenue (714) 889-1500 Irvine Irvine Spectrum 71 Fortune Drive (949) 788-9998 Los Angeles The Grove 189 The Grove Drive (323) 634-0511 Marina del Rey 4142 Via Marina (310) 306-3344 Mission Viejo The Shops at Mission Viejo 42 The Shops at Mission Viejo (949) 364-6200 Newport Beach Fashion Island Mall 1141 Newport Center Drive (949) 720-8333 Oxnard The Collection at RiverPark 600 Town Center Drive (805) 278-8878 Pasadena 2 West Colorado Boulevard (626) 584-6000 Pleasanton Stoneridge Mall 1350 Stoneridge Mall Road (925) 463-1311 Rancho Cucamonga Victoria Gardens Mall 12379 N.