Shoukei Matsumoto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mop Bucket Vs Micromatic

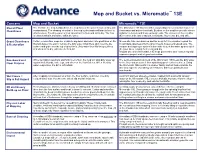

™ Mop and Bucket vs. Micromatic 13E Concern Mop and Bucket Micromatic™ 13E Overall Floor The first time the mop is dipped into the mop bucket, the water becomes dirty and The Micromatic 13E floor scrubber always dispenses a solution mixture of Cleanliness contaminated. The cleaning chemical in the mop bucket water will start to lose its clean water and active chemicals. Brushes on the scrubber provide intense effectiveness. The dirty water is then spread on the floor and left to dry. The floor agitation to loosen and break up tough soils. The vacuum on the scrubber is left wet with dirt and grime still in the water. then removes the water and dirt, leaving the floor clean, dry, and safe. Grout Cleanliness Cotton or microfiber mops are unable to dig down and reach into grout lines on tile Micromatic 13E uses brushes and the weight of the machine to push the & Restoration floors to loosen the soil or remove the dirty water. Mop fibers skim over the tile brush bristle tips deep into the grout lines to loosen embedded soils. The surface and glide over the top of grout lines. Dirty water then fills the grout lines vacuum and squeegee system is then able to suck the water up and out of and when left to dry, will leave behind dirt. the grout lines, leaving them clean and dry. Regular use of the Micromatic 13E helps prevent the time consuming and expensive project work of grout restoration. Baseboard and While swinging mops back and forth over a floor, the mop will sling dirty water up The semi-enclosed scrub deck of the Micromatic 13E keeps the dirty water Floor Fixtures against baseboards, table legs, and other on the floor fixtures. -

Beesupplies2017.Pdf

Hive Bodies and Components Item Price 5 frame wooden nuc box $37.50 assembled nuc $37.50 Plastic Nuc Box $10.95 9-5/8'' unassembled ponderosa pine hive body $15.00 6-5/8'' unassembled pine super $11.50 5-3/4'' unassembled pine super $10.50 9-5/8'' unassembled cypress hive body $22.00 6-5/8'' unassembled cypress super $17.00 5-3/4'' unassembled cypress super $14.75 9-5/8'' assembled & painted pine hive body $26.50 6-5/8'' assembled & painted pine super $22.50 5-3/4'' assembled & painted pine super $21.50 hive stand cypress (8 & 10 frame) $19.75 cypress screened bottom board (8 & 10 frame) $25.00 cypress solid reversible bottom board (8 & 10 frame) $19.75 Unassembled cypress telescoping cover $23.00 assembled cypress telescoping cover (8 & 10 frame) $28.50 assembled painted pine telescoping cover $26.75 assembled unpainted pine telescoping cover $24.50 cypress inner cover (8 or 10 frame) $14.00 migratory flat cover $13.50 Painted Migratory Cover $15.00 Nails for Hives $3.50 25 hive staples $2.00 plastic bound queen excluder $4.85 metal bound queen excluder (8 or 10 frame) $8.25 entrance reducer (8 or 10 frame) $1.50 propolis trap $8.50 bottom pollen trap $63.40 Hive bodies and Components cont. cypress double screen $19.00 cypress top moving screen $11.00 plastic 9 frame spacer $13.95 8 frame spacer for 10 frame equipment $0.60 9 frame spacer for 10 frame equipment $0.60 deep drone frames $2.75 medium drone frames $2.75 10 frame starter kit $189.50 Observation Hive (bees not included) $899.00 Observation Hive with Bees $1,099.00 Frame Assembly -

Design, Development and Evaluation of Erlotinib-Loaded Hybrid Nanoparticles for Targeted Drug Delivery to Nonsmall Cell Lung Cancer" (2015)

University of Tennessee Health Science Center UTHSC Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations (ETD) College of Graduate Health Sciences 5-2015 Design, Development and Evaluation of Erlotinib- Loaded Hybrid Nanoparticles for Targeted Drug Delivery to NonSmall Cell Lung Cancer Bivash Mandal University of Tennessee Health Science Center Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uthsc.edu/dissertations Part of the Pharmaceutics and Drug Design Commons Recommended Citation Mandal, Bivash , "Design, Development and Evaluation of Erlotinib-Loaded Hybrid Nanoparticles for Targeted Drug Delivery to NonSmall Cell Lung Cancer" (2015). Theses and Dissertations (ETD). Paper 166. http://dx.doi.org/10.21007/etd.cghs.2015.0196. This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Graduate Health Sciences at UTHSC Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (ETD) by an authorized administrator of UTHSC Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Design, Development and Evaluation of Erlotinib-Loaded Hybrid Nanoparticles for Targeted Drug Delivery to NonSmall Cell Lung Cancer Document Type Dissertation Degree Name Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) Program Pharmaceutical Sciences Research Advisor George C. Wood, Ph.D. Committee Himanshu Bhattacharjee, Ph.D. James R. Johnson, Ph.D. Timothy D. Mandrell, Ph.D. Duane D. Miller, Ph.D. DOI 10.21007/etd.cghs.2015.0196 This dissertation is available at UTHSC Digital Commons: https://dc.uthsc.edu/dissertations/166 Design, Development and Evaluation of Erlotinib-Loaded Hybrid Nanoparticles for Targeted Drug Delivery to Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer A Dissertation Presented for The Graduate Studies Council The University of Tennessee Health Science Center In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy From The University of Tennessee By Bivash Mandal May 2015 Portions of Chapter 1 © 2013 by Elsevier. -

Remote Controlled Autonomous Floor Cleaning Robot

International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering (IJRTE) ISSN: 2277-3878, Volume-8, Issue-2S11, September 2019 Remote Controlled Autonomous Floor Cleaning Robot R.Senthil Kumar, Vaisakh KP, Sayanth A Kumar, Gaurav Dasgupta Abstract— Cleanbot is a smartphone-controlled floor cleaning paradigm shift in the field of mopping to more robot which cleans a dirty floor automatically using a set of technologically sound machinery. commands given to your device by a smartphone. Cleanbot has two modes of cleaning – Mopping and Wiping. These two II. HISTORY AND EVOLUTION OF MOPPING variations can be dedicatedly used in various applications in the cleaning industry and can break the manual labor in terms of A. History of Mopping cleaning is concerned. The device communicates through Bluetooth technology via a HC05 Bluetooth module that will be The mop has been a very important invention in terms of used to exchange commands to the microcontroller -Arduino addressing the history of society as well as being a part of the UNO. The robot is given power by a 12V lead-acid battery, the apt evolution of house wares#. Thomas W. Steward, an voltage requirement used for all motors here. The driver motors African-American inventor invented the mop. Steward's deck uses 100 rpm type while the run with mops 60rpm plastic geared mop was made of yarn and became an instant hit in terms of motors attached to them. Essentially Cleanbot has a very discrete design in terms of compactness and usability as it is very handy usability in household and cleaning in industries and factories and easy to operate. -

Spying with Your Robot Vacuum Cleaner: Eavesdropping Via Lidar Sensors

Spying with Your Robot Vacuum Cleaner: Eavesdropping via Lidar Sensors Sriram Sami Yimin Dai Sean Rui Xiang Tan National University of Singapore National University of Singapore National University of Singapore [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Nirupam Roy Jun Han University of Maryland, College Park National University of Singapore [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT Victim’s Home Eavesdropping on private conversations is one of the most common “194-70-6839” “194-70-6839” yet detrimental threats to privacy. A number of recent works have explored side-channels on smart devices for recording sounds with- out permission. This paper presents LidarPhone, a novel acoustic side-channel attack through the lidar sensors equipped in popular commodity robot vacuum cleaners. The core idea is to repurpose the lidar to a laser-based microphone that can sense sounds from subtle vibrations induced on nearby objects. LidarPhone carefully processes and extracts traces of sound signals from inherently noisy laser reflections to capture privacy sensitive information (such as “Listening” via Lidar Sensor Remote Attacker speech emitted by a victim’s computer speaker as the victim is en- gaged in a teleconferencing meeting; or known music clips from Figure 1: Figure depicts the LidarPhone attack, where the ad- television shows emitted by a victim’s TV set, potentially leaking versary remotely exploits the lidar sensor equipped on a vic- the victim’s political orientation or viewing preferences). We imple- tim’s robot vacuum cleaner to capture parts of privacy sensi- ment LidarPhone on a Xiaomi Roborock vacuum cleaning robot and tive conversation (e.g., credit card, bank account, and/or so- evaluate the feasibility of the attack through comprehensive real- cial security numbers) emitted through a computer speaker world experiments. -

Working Safer and Easier for Janitors, Custodians, and Housekeepers

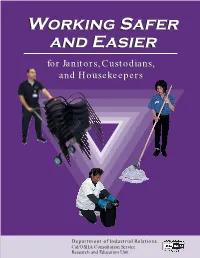

WorkingWorking SaferSafer andand EasierEasier forfor Janitors,Janitors,Custodians, Custodians, andand HousekeepersHousekeepers Department of Industrial Relations Cal/OSHA Consultation Service Research and Education Unit WWORKINGORKING SSAFERAFER ANDAND EEASIERASIER Publication Information Working Safer and Easier: for Janitors, Custodians, and Housekeepers was developed and prepared for publication by the Cal/OSHA Consultation Service, Research and Education Unit, Division of Occupational Safety and Health, California Department of Industrial Relations. It was distributed under the provisions of the Library Distribution Act and Government Code Section 11096. Published 2005 by the California Department of Industrial Relations This booklet is not meant to be a substitute for, or a legal interpretation of, the occupational safety and health standards. Please see the California Code of Regulations, Title 8, or the Labor Code for detailed and exact information, specifications, and exceptions. The display or use of particular products in this booklet is for illustrative purposes only and does not constitute an endorsement by the Department of Industrial Relations. In Memory of Douglas Binion WORKING SAFER AND EASIER Contents INTRODUCTION FACT SHEETS FOR CREATING A SAFER WORKPLACE Tips for Managers 1. A Safe and Healthful Workplace 2. Commitment to Safety and Health 3. Effective Communication 4. Training 5. Work Assignment 6. Productivity and Rest Breaks 7. Buying Equipment and Supplies 8. Equipment Maintenance Program General Guidelines 9. Know Your Body 10. Organizing Work 11. Workplace Awareness 12. Preventing Slips, Trips, and Falls 13. Chemicals and Their Health Effects 14. Procedures for Safe Handling and Use of Chemicals 15. Using Personal Protective Equipment Using Ergonomics 16. Moving Barrels/Carts 17. Emptying Office Trash Cans 18. -

2014 Budget Proposals – Import Cess

HS HS Code(II) Hdg(I) Description (III) Rate of Cess(IV) Unit 1st Crieteria 2nd criteria 02.01 Meat of bovine animals, fresh or chilled. 0201.10 - Carcasses and half-carcasses 30% or Rs. 225/= per kg kg 30% 225 0201.20 - Other cuts with bone in 30% or Rs. 225/= per kg kg 30% 225 0201.30 - Boneless 30% or Rs. 225/= per kg kg 30% 225 02.02 Meat of bovine animals, frozen. 0202.10 - Carcasses and half-carcasses 30% or Rs. 225/= per kg kg 30% 225 0202.20 - Other cuts with bone in 30% or Rs. 225/= per kg kg 30% 225 0202.30 - Boneless 30% or Rs. 225/= per kg kg 30% 225 02.03 Meat of swine, fresh, chilled or frozen. - Fresh or chilled : 0203.11 -- Carcasses and half-carcasses 30% or Rs. 225/= per kg kg 30% 225 0203.12 -- Hams, shoulders and cuts thereof, with bone in 30% or Rs. 225/= per kg kg 30% 225 0203.19 -- Other 30% or Rs. 225/= per kg kg 30% 225 - Frozen : 0203.21 -- Carcasses and half-carcasses 30% or Rs. 225/= per kg kg 30% 225 0203.22 -- Hams, shoulders and cuts thereof, with bone in 30% or Rs. 225/= per kg kg 30% 225 0203.29 -- Other 30% or Rs. 225/= per kg kg 30% 225 02.04 Meat of sheep or goats, fresh, chilled or frozen. 0204.10 - Carcasses and half-carcasses of lamb, fresh or chilled 30% or Rs. 225/= per kg kg 30% 225 - Other meat of sheep, fresh or chilled: 0204.21 -- Carcasses and half-carcasses 30% or Rs. -

SRI LANKA EXPORT DEVELOPMENT ACT, No

2 A Government Notifications SRI LANKA EXPORT DEVELOPMENT ACT, No. 40 OF 1979 Order under Section 14 BY virtue of powers vested in me by Section 14 (1) of the Sri Lanka Export Development Act, No. 40 of 1979, I, Malik Samarawickrama, Minister of Development Strategies and International Trade with the concurrence of the Minister of Finance, do by this Order declare that with effect from 12.11.2016, a Cess shall be charged, levied and paid on all goods enumerated in Column III of the Schedule hereto at rates specified in the corresponding entry in Column IV in the same Schedule hereto, on the aggregate of a sum equivalent to their value for Customs duty purposes at the time of importation and a sum equivalent to ten per centum (10%) of such value, provided however, that; (1) Wherever more than one rate is specified in Column IV of the Schedule hereto, the applicable rate for the purpose of calculating the Cess payable shall be that rate the application of which results in a higher amount being payable as Cess. (2) The Cess hereby imposed shall not apply to; (i) Ayurveda, Siddha and Unani raw and prepared drugs and medicinal plants specified by Notification published in Gazette by the Director General of Customs in consultation with the Secretary to the Ministry which is responsible to the subject of Ayurveda, and Ayurveda, Siddha and Unani preparations (other than cosmetics preparations) imported, subject to the approval of the Secretary to the Treasury. (ii) Any product or preparation registered as drug or device under the Cosmetics Devices and Drugs Act. -

Sri Lanka Tea Board As Wholly of Sri Lankan ---- Rs

1A Import Cess changes with effect from 09th November 2012 1 Schedule 02.01 Meat of bovine animals, fresh or chilled. 0201.10 - Carcasses and half-carcasses 30% or Rs. 200/= per kg 0201.20 - Other cuts with bone in 30% or Rs. 200/= per kg 0201.30 - Boneless 30% or Rs. 200/= per kg 02.02 Meat of bovine animals, frozen. 0202.10 - Carcasses and half-carcasses 30% or Rs. 200/= per kg 0202.20 - Other cuts with bone in 30% or Rs. 200/= per kg 0202.30 - Boneless 30% or Rs. 200/= per kg 02.03 Meat of swine, fresh, chilled or frozen. - Fresh or chilled : 0203.11 -- Carcasses and half-carcasses 30% or Rs. 200/= per kg 0203.12 -- Hams, shoulders and cuts thereof, with bone in 30% or Rs. 200/= per kg 0203.19 -- Other 30% or Rs. 200/= per kg - Frozen : 0203.21 -- Carcasses and half-carcasses 30% or Rs. 200/= per kg 0203.22 -- Hams, shoulders and cuts thereof, with bone in 30% or Rs. 200/= per kg 0203.29 -- Other 30% or Rs. 200/= per kg 02.04 Meat of sheep or goats, fresh, chilled or frozen. 0204.10 - Carcasses and half-carcasses of lamb, fresh or chilled 30% or Rs. 200/= per kg - Other meat of sheep, fresh or chilled: 0204.21 -- Carcasses and half-carcasses 30% or Rs. 200/= per kg 0204.22 -- Other cuts with bone in 30% or Rs. 200/= per kg 0204.23 -- Boneless 30% or Rs. 200/= per kg 0204.30 - Carcasses and half-carcasses of lamb, frozen 30% or Rs. -

Common Fund for Commodities

Discover Technical Paper No. 56 natural fibres 2009 COMMON FUND FOR COMMODITIES PROCEEDINGS OF THE SYMPOSIUM ON NATURAL FIBRES Rome 20 October 2008 FAO, Rome Supported by the Common Fund for Commodities The Symposium and publication of the Proceedings is sponsored by the CFC and FAO. This document is published without formal editing. Any presentation or part of it, published in these Proceedings, represents the opinion of the author(s) and does not necessarily reflect the official policy of sponsoring organizations, or the institution within which the presenter is affiliated unless this is clearly specified. Additionally, the author(s) is/are fully responsible for the contents of the presentation and for any claim or disclaim therein. Common Fund for Commodities Stadhouderskade 55, 1072 AB Amsterdam, The Netherlands Postal Address: PO Box 74656, 1070 BR Amsterdam, The Netherlands Tel: (31-20) 5754949 E.mail: [email protected] Fax: (31-20) 6760231 website: www.common-fund.org Copyright © Common Fund for Commodities 2009 The contents of this report may not be reproduced, stored in a data retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission of the Common Fund for Commodities, except that reasonable extracts may be made for the purpose of comment or review provided the Common Fund for Commodities is acknowledged as the source. COMMON FUND FOR COMMODITIES PROCEEDINGS OF THE SYMPOSIUM ON NATURAL FIBRES Rome 20 October 2008 iii Contents FOREWORD iv OVERVIEW OF THE SYMPOSIUM v PRÉSENTATION GÉNÉRALE -

Windsor Cricket Automop

Cricket™ Automop Do More With Less. There are problems/challenges and benefits to a mop and an autoscrubber. The Cricket fills the need in-between. • Safety » Leaves floor dry » Reduces slip-n-falls » “Ergo-mopping” Reduces the swinging & wringing » Fewer injuries • Hygienic/Green » Clean with clean water vs. spreading dirty water » Quiet <52 dBA » Daytime Cleaning • Productivity » 5x the cleaning rate of a mop in open areas » Add on tools provide ability to clean in small/tight areas » Greater productivity than a 20" pad assist autoscrubber • Simple » Simple to operate & push » Maintenance free: no batteries, no cords, always available » Footprint similar to a mop & bucket Low Labor High Labor PDIR Low Overall Cost High Overall Cost Daily & Interim Maintenance Low Chemical Usage High Chemical Usage The Cricket AutoMop can be used for daily hard floor cleaning or as an interim process between Greener Less Green autoscrubbing and deep cleaning. Preventative Daily Interim Restorative Why Did Windsor Create The Cricket? Windsor recognized a need for a cleaning solution between a mop & bucket and an autoscrubber in function, capability and price. It is important to recognize that innovative solutions do not need to rely heavily on technology but that innovation can be found in creative ways of applying tried and true systems. As an important part of Windsor’s PDIR program, the Cricket Automop is a Daily & Interim hard floor solution. The Cricket is not designed to replace the mop and bucket nor an autoscrubber...it was created to fill a need in between. Additionally, where autoscrubbers are in use the Cricket can fill a need for effective and safe cleaning between regular scrubbing. -

Roscoleum™ User Instructions

Roscoleum™ User Instructions INSTRUCTIONS FOR BREAKING IN THE ROSCOLEUM STUDIO FLOORS TO BE USED AS A BALLET FLOOR Note: For a new floor it may be necessary to scrub twice depending on the first application. Two people will be needed and process requires three buckets and three new mops, one for each process. Once a mop has been designated for a step, DO NOT USE IT FOR ANOTHER STEP. Mop buckets should be thoroughly clean before starting. Step 1: Sweep floor first. Step 2: Using a clean bucket and mop, the 1st person should mix 2-1/2 cups of floor stripper to one pail (4 gallons) of water. It is recommended to use Red Line Stripper from Crown Chemicals, which is a heavy duty stripper. Once mixed, proceed to put the stripper on the Roscoleum floor one strip (panel) at a time. Step 3: 2nd person follows behind after approx. 5 minutes with a floor scrubber using a green pad. Step 4: 1st person follows the person with the scrubber and using a bucket of clean water, mops up the floor stripper. It is important to use a clean mop, not the mop used to put down the cleaner. Step 5: 2nd person follows behind the person who is taking up the floor stripper with a bucket (4 gallons) of clean water mixed with 1/2 quart of white vinegar. This neutralizes any soap that remains on the floor and is the most important part of this maintenance process. Note: On a monthly basis the floor should be washed and cleaned, but it should not be necessary to repeat this process..