Of the Atakapa Language Accompanied by Text Material

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C

REPORT NO. PN-1-210205-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 02/05/2021 Federal Communications Commission 45 L Street NE PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 APPLICATIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. City, State Applicant or Licensee Status Date Status 0000132840 Assignment AM WING 25039 Main 1410.0 DAYTON, OH ALPHA MEDIA 01/27/2021 Accepted of LICENSEE LLC For Filing Authorization From: ALPHA MEDIA LICENSEE LLC To: Alpha Media Licensee LLC Debtor in Possession 0000132974 Assignment FM KKUU 11658 Main 92.7 INDIO, CA ALPHA MEDIA 01/27/2021 Accepted of LICENSEE LLC For Filing Authorization From: ALPHA MEDIA LICENSEE LLC To: Alpha Media Licensee LLC Debtor in Possession 0000132926 Assignment AM WSGW 22674 Main 790.0 SAGINAW, MI ALPHA MEDIA 01/27/2021 Accepted of LICENSEE LLC For Filing Authorization From: ALPHA MEDIA LICENSEE LLC To: Alpha Media Licensee LLC Debtor in Possession 0000132914 Assignment FM WDLD 23469 Main 96.7 HALFWAY, MD ALPHA MEDIA 01/27/2021 Accepted of LICENSEE LLC For Filing Authorization From: ALPHA MEDIA LICENSEE LLC To: Alpha Media Licensee LLC Debtor in Possession 0000132842 Assignment AM WJQS 50409 Main 1400.0 JACKSON, MS ALPHA MEDIA 01/27/2021 Accepted of LICENSEE LLC For Filing Authorization From: ALPHA MEDIA LICENSEE LLC To: Alpha Media Licensee LLC Debtor in Possession Page 1 of 66 REPORT NO. PN-1-210205-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 02/05/2021 Federal Communications Commission 45 L Street NE PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 APPLICATIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. -

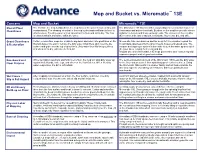

Mop Bucket Vs Micromatic

™ Mop and Bucket vs. Micromatic 13E Concern Mop and Bucket Micromatic™ 13E Overall Floor The first time the mop is dipped into the mop bucket, the water becomes dirty and The Micromatic 13E floor scrubber always dispenses a solution mixture of Cleanliness contaminated. The cleaning chemical in the mop bucket water will start to lose its clean water and active chemicals. Brushes on the scrubber provide intense effectiveness. The dirty water is then spread on the floor and left to dry. The floor agitation to loosen and break up tough soils. The vacuum on the scrubber is left wet with dirt and grime still in the water. then removes the water and dirt, leaving the floor clean, dry, and safe. Grout Cleanliness Cotton or microfiber mops are unable to dig down and reach into grout lines on tile Micromatic 13E uses brushes and the weight of the machine to push the & Restoration floors to loosen the soil or remove the dirty water. Mop fibers skim over the tile brush bristle tips deep into the grout lines to loosen embedded soils. The surface and glide over the top of grout lines. Dirty water then fills the grout lines vacuum and squeegee system is then able to suck the water up and out of and when left to dry, will leave behind dirt. the grout lines, leaving them clean and dry. Regular use of the Micromatic 13E helps prevent the time consuming and expensive project work of grout restoration. Baseboard and While swinging mops back and forth over a floor, the mop will sling dirty water up The semi-enclosed scrub deck of the Micromatic 13E keeps the dirty water Floor Fixtures against baseboards, table legs, and other on the floor fixtures. -

U.S. Et Al V. Conocophillips Co., and Sasol North America, Inc. NRD

Case 2:10-cv-01556 Document 1-5 Filed 10/12/10 Page 1 of 54 PageID #: 230 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA LAKE CHARES DIVISION UNITED STATES OF AMERICA and STATE OF LOUISIANA Plaintiffs, CIVIL ACTION NO. v. JUDGE CONOCOPHILLIPS COMPANY MAGISTRATE JUDGE and SASOL NORTH AMERICA INC., Settling Defendants. CONSENT DECREE FOR NATURA RESOURCE DAMAGES This Consent Decree is made and entered into by and among Plaintiffs, the United States of America ("United States"), on behalf of the United States Deparment ofthe Interior, acting through the United States Fish and Wildlife Service ("DOI/USFWS"), and the National Oceanc and Atmospheric Administration ("NOAA") of the United States Deparment of Commerce, and the Louisiana Deparment of Wildlife and Fisheries ("LDWF") and the Louisiana Deparment of Environmental Quality ("LDEQ") for the State of Louisiana (State), and Settling Defendants ConocoPhilips Company and Sasol North America Inc. (collectively the "Settling Defendants"). Case 2:10-cv-01556 Document 1-5 Filed 10/12/10 Page 2 of 54 PageID #: 231 I. BACKGROUN A. Contemporaneously with the lodging of this Consent Decree, the United States, on behalf of the Administrator of the United States Environmental Protection Agency ("EP A"), NOAA, and the DOI/SFWS, and LDEQ and LDWF have fied a Complaint in this matter against Settling Defendants pursuant to Sections 106 and 107 of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act ("CERCLA"), 42 U.S.c. §§ 9606 and 9607, Section 311(f) of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act (also known as the Clean Water Act or CWA), 33 U.S.C. -

The Caddo After Europeans

Volume 2016 Article 91 2016 Reaping the Whirlwind: The Caddo after Europeans Timothy K. Perttula Heritage Research Center, Stephen F. Austin State University, [email protected] Robert Cast Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita Part of the American Material Culture Commons, Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Other American Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Cite this Record Perttula, Timothy K. and Cast, Robert (2016) "Reaping the Whirlwind: The Caddo after Europeans," Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State: Vol. 2016, Article 91. https://doi.org/10.21112/.ita.2016.1.91 ISSN: 2475-9333 Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita/vol2016/iss1/91 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Regional Heritage Research at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reaping the Whirlwind: The Caddo after Europeans Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. This article is available in Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita/vol2016/iss1/91 -

Nelly, TLC, and Flo Rida Have Announced That They Will Be Hitting the Road Together for an Epic Tour Across North America

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: Bridget Smith v.845.583.2179 Photos & Interviews may be available upon request [email protected] NELLY, TLC AND FLO RIDA ANNOUNCE SUMMER AMPHITHEATER TOUR; INCLUDES PERFORMANCE AT BETHEL WOODS ON FRIDAY, AUGUST 9TH Tickets On-Sale Friday, March 15th at 10 AM March 11, 2019 (BETHEL, NY) – Music icons Nelly, TLC, and Flo Rida have announced that they will be hitting the road together for an epic tour across North America. The Billboard chart-topping hit makers will join forces to bring a show like no other to outdoor amphitheater stages throughout the summer – including a performance at Bethel Woods Center for the Arts, at the historic site of the 1969 Woodstock festival in Bethel, NY, on Friday, August 9th. Fans can expect an incredible, non-stop party with each artist delivering hit after hit all night long. Tickets go on sale to the general public beginning Friday, March 15th at 10 AM local time at www.BethelWoodsCenter.org, www.Ticketmaster.com, Ticketmaster outlets, or by phone at 1.800.745.3000. Citi is the official presale credit card for the tour. As such, Citi card members will have access to purchase presale tickets beginning Tuesday, March 12th at 12 PM local time until Thursday, March 14th at 10 PM local time through Citi’s Private Pass program. For complete presale details visit www.citiprivatepass.com. About Nelly: Nelly is a Diamond Selling, Multi-platinum, Grammy award-winning rap superstar, entrepreneur, philanthropist and TV/Film actor. Within the United States, Nelly has sold in excess of 22.5 million albums; on a worldwide scale, he has been certified gold and/or platinum in more than 35 countries – estimates bring his total record sales to over 40 Million Sold. -

Water Quality Monitoring in the Bayou Teche Watershed

Water Quality Monitoring in the Bayou Teche Watershed Researchers: Dr. Whitney Broussard III Dr. Jenneke M. Visser Kacey Peterson Mark LeBlanc Project type: Staff Research Funding sources: Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality, Environmental Protection Agency Status: In progress Summary The historic Bayou Teche is an ancient distributary of the Mississippi River. Some 3,000-4,000 years ago, the main flow of the Mississippi River followed the Bayou Teche waterway. This explains the long, slow bends of the small bayou and its wide, sloping banks. The Atákapa-Ishák nation named the bayou “Teche” meaning snake because the course of the bayou looked like a giant snake had laid down to rest, leaving its mark on the land. Many years later, the first Acadians arrived in Southwestern Louisiana via Bayou Teche. They settled along its banks and used the waterway as a means of transportation and commerce. The bayou remains to this day an iconic cultural figure and an important ecological phenomenon. Several modern events have reshaped the quality and quantity of water in Bayou Teche. After the catastrophic flood of 1927, the United States Congress authorized the US Army Corps of Engineers to create the first comprehensive flood management plan for the Mississippi River. One important element of this plan was the construction of the West Atchafalaya Basin Protection Levee, which, in conjunction with the East Protection Levee, allows the Corps of Engineers to divert a substantial amount of floodwaters out of the Mississippi River into the Atchafalaya Spillway, and away from major urban centers like Baton Rouge and New Orleans. -

Myths and Legends Byway to Experience 17 Oberlin 21 Legendary Tales from This Region Firsthand

LOOK FOR THESE SIGNS ALONG THIS See reverse side for detailed 11 rest BYWAY information about stops Woodworth along this byway. Leesville MYTHS LEGEND 23 2 Miles AND 1 Informational Kiosks 0 1.25 2.5 5 7.5 a Points of Interest Kisatchie National Forest LEGENDS Fort Polk North 1 inch equals approximately 5 miles a 111 Local Tourist Information Centers New Llano 1 8 Fort Polk State Welcome Centers South Cities and Communities on 111 e Forest Hill 171 or near Byways Fort Polk Military Reservation RAPIDESPARISH 10 399 State Parks North VERNON PARISH 171 6 24 4 Water Bodies, Rivers and Bayous 3 Fullerton State Highways Connected McNary Evans f with Byways 399 Glenmora Neame 10 458 463 Interstate Highways 399 10 Hauntings, hidden treasures and hangings are all U.S. Highways Texas Kisatchie Pitkin part of the folktales that have been passed down National Forest 5 10 Urbanized Areas 113 throughout the region now designated as the Myths Rosepine Parish Line 1146 g and Legends Byway. Explore a former no-man’s- 3226 377 171 7 land once populated by outlaws and gunslingers. 464 Ludington 399 Miles Fish on the Calcasieu River, the waterway that 1146 i 021.25 .5 57.5 c d 16 Legend 113 1 inch equals approximately 5 miles infamous buccaneer Jean Lafitte is known to have 111 3226 Elizabeth 112 165 190 9 22 Myths and traveled. Search for the ghost-protected buried 3099 10 8 Sugartown j Legends treasure of two Jayhawkers—pro-Union Civil War 190 13 26 h 10 20 Byway rebel guerrillas—from the 1800s. -

CHARENTON BRIDGE HAER No. LA-43 (Bridge Recall No

CHARENTON BRIDGE HAER No. LA-43 (Bridge Recall No. 008970) Carries Louisiana Highway 182 (LA 182) over Charenton Drainage and Navigation Canal Baldwin St. Mary Parish Louisiana PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA REDUCED COPIES OF MEASURED & INTERPRETIVE DRAWINGS FIELD RECORDS HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street, NW Washington, DC 20240 HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD CHARENTON BRIDGE (Bridge Recall No. 008970) HAER No. LA-43 Location: Carries Louisiana Highway 182 (LA 182) over Charenton Drainage and Navigation Canal (Charenton Canal) in the town of Baldwin, St. Mary Parish, Louisiana. The Charenton Bridge (Bridge Recall No. 008970) is located at latitude 29.825298 north, longitude - 91.537959 west.1 The coordinate represents the center of the bridge. It was obtained in 2016 by plotting its location in Google Earth. The location has no restriction on its release to the public. Present Owner: State of Louisiana. Present Use: Vehicular and pedestrian traffic. Significance: The Charenton Bridge is significant as an important example of a distinctive truss type. The bridge’s significant design feature is its K-truss configuration, characterized by the arrangement of vertical and diagonal members to form a “K” in each truss panel. The K-truss is a rare variation both nationally and in Louisiana, where there are only three extant examples of the bridge type.2 The Charenton Bridge retains good integrity and clearly conveys the significant design features of the through K-truss. It was determined eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places (National Register) in 2013 under Criterion C: Engineering at the state level of significance.3 Historian(s): Angela Hronek, Cultural Resource Specialist, and Robert M. -

Prehistoric Settlements of Coastal Louisiana. William Grant Mcintire Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1954 Prehistoric Settlements of Coastal Louisiana. William Grant Mcintire Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Mcintire, William Grant, "Prehistoric Settlements of Coastal Louisiana." (1954). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 8099. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/8099 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HjEHisroaic smm&ws in coastal Louisiana A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Geography and Anthropology by William Grant MeIntire B. S., Brigham Young University, 195>G June, X9$k UMI Number: DP69477 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI DP69477 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest: ProQuest LLC. -

Capitol Federal Big Money Play of the Game Text Contest Contest Rules

Capitol Federal Big Money Play of the Game Text Contest Contest Rules These contest rules are specific to the Capitol Federal Big Money Play of the Game Text Contest (the “Contest”) conducted by Entercom Kansas, LLC d/b/a the Kansas City Chiefs Radio Network (the “Contest Administrator”) (see complete list of stations in Attachment A at the end of these rules). A copy of these specific Contest rules is available online at www.1065thewolf.com/rules and www.radio.com/610sports/contest-rules. WHO CAN ENTER 1. Eligible entrants must be eighteen (18) years of age or older and legal U.S. residents of Arkansas, Iowa, Illinois, Kansas, Louisiana, Missouri, Nebraska, Oklahoma, South Dakota, or Texas as of the date of entry in the Contest. 2. Employees (including, without limitation, part-time or temporary employees) of the Contest Administrator, Contest sponsors and their respective parent entities, subsidiaries, affiliated companies and advertising and promotion agencies, at any time during the applicable contesting period and the immediate family and other household members (i.e., spouses, parents, grandparents, children, grandchildren, roommates, housemates, significant others, partners, siblings (half and full) and the steps of each of the foregoing) of each of the above are NOT eligible to enter and/or to win the Contest. HOW TO ENTER 3. NO PURCHASE OR PAYMENT OF ANY KIND IS NECESSARY TO ENTER OR WIN THIS CONTEST. A PURCHASE WILL NOT INCREASE YOUR CHANCES OF WINNING. 4. To enter, during each of the Contest Entry Periods set forth in Section 4(a) below (each a “Contest Entry Period” and together the “Contest Entry Periods”) text PLAY to SMS shortcode 26004. -

Native American Languages, Indigenous Languages of the Native Peoples of North, Middle, and South America

Native American Languages, indigenous languages of the native peoples of North, Middle, and South America. The precise number of languages originally spoken cannot be known, since many disappeared before they were documented. In North America, around 300 distinct, mutually unintelligible languages were spoken when Europeans arrived. Of those, 187 survive today, but few will continue far into the 21st century, since children are no longer learning the vast majority of these. In Middle America (Mexico and Central America) about 300 languages have been identified, of which about 140 are still spoken. South American languages have been the least studied. Around 1500 languages are known to have been spoken, but only about 350 are still in use. These, too are disappearing rapidly. Classification A major task facing scholars of Native American languages is their classification into language families. (A language family consists of all languages that have evolved from a single ancestral language, as English, German, French, Russian, Greek, Armenian, Hindi, and others have all evolved from Proto-Indo-European.) Because of the vast number of languages spoken in the Americas, and the gaps in our information about many of them, the task of classifying these languages is a challenging one. In 1891, Major John Wesley Powell proposed that the languages of North America constituted 58 independent families, mainly on the basis of superficial vocabulary resemblances. At the same time Daniel Brinton posited 80 families for South America. These two schemes form the basis of subsequent classifications. In 1929 Edward Sapir tentatively proposed grouping these families into superstocks, 6 in North America and 15 in Middle America. -

Emergency Alert System Plan

State Emergency Alert System Plan 2013 i i ii Record of Changes Change Location of Change Date of Date Entered Person Making Number Change Change iii Contents Promulgation Letter ....................................................................................................................................... i Concurrence Signatures…………………………………………………………………………………….ii Record of Changes…...…………………………………………………………………………………….iii Purpose .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Authority ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 1 General Considerations ................................................................................................................................. 1 Definitions..................................................................................................................................................... 2 Concept of Operation .................................................................................................................................... 3 Methods of Access for System Activation .................................................................................................... 3 A. State Activation