Again in the Age of Shenanigans: Kehinde Wiley X Spike Lee,” Interview Magazine, June 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibiliography

Parodies of Ownership: Hip-Hop Aesthetics and Intellectual Property Law Richard L. Schur http://www.press.umich.edu/titleDetailDesc.do?id=822512 The University of Michigan Press, 2009. Bibiliography A&M Records v. Napster. 2001. 239 F.3d 1004 (9th Cir.). Adler, Bill. 2006. “Who Shot Ya: A History of Hip Hop Photography.” Total Chaos: The Art and Aesthetics of Hip Hop. Ed. Jeff Chang. New York: Basic Books. 102–116. Alim, Salim. 2006. Roc the Mic Right: The Language of Hip Hop Culture. New York: Routledge. Alkalimat, Abdul. 2002a. Editor’s Notes. “Archive of Malcolm X For Sale.” By David Chang. February 20. www.h-net.org/~afro-am/. People can ‹nd the dis- cussion loss there H-Afro-Am. August 9, 2004. http://h-net.msu.edu/cgi- bin/logbrowse.pl?trx=vx&list=H-Afro-Am&month=0202&week=c&msg=c PR4wypSByppLKU61e5Diw&user=&pw=. Alkalimat, Abdul. 2002b. Editor’s Notes. “Archive of Malcolm X For Sale.” By Gerald Horne. February 20. H-Afro-Am. August 9, 2004. http://h- net.msu.edu/cgi-bin/logbrowse.pl?trx=vx&list=H-Afro-Am&month=0202& week=c&msg=JQnoJ7FS8tJmazqZ6J5S3Q&user=&pw=. Allen, Ernest, Jr. 2002. “Du Boisian Double Consciousness: The Unsustainable Ar- gument.” Massachusetts Review 43.2: 215–253. Alridge, Derrick. 2005. “From Civil Rights to Hip Hop: Toward a Nexus of Ideas.” Journal of African American History 90.3: 226–252. Ancient Egyptian Order of Nobles of the Mystic Shrine v. Michaux. 1929. 279 U.S. 737. Angelo, Bonnie. 1994. “The Pain of Being Black: An Interview with Toni Morri- son.” Conversations with Toni Morrison. -

Fort Gansevoort

FORT GANSEVOORT March Madness 5 Ninth Avenue, New York, NY, 10014 On View: Friday March 18 – May 1, 2016 Opening Reception: March 18, 6-9pm When sports and art collide with the impact of “March Madness,” a show of 28 artists opening March 18 at Fort Gansevoort, our games become metaphors, our heroes are transformed, even our golf bags reveal secrets. The artist’s eye finds the corruption, violence and racism behind the scoreboard, and the artist’s hand enhances the protest. To fans, “March Madness” refers to the hyped fun and games of the current national college basketball tournament. To Hank Willis Thomas and Adam Shopkorn, organizers of these 44 works, it reflects the classic spirit of Tommie Smith and John Carlos raising the black power salute at the 1968 Olympics, of Leni Riefenstahl’s film of the 1936 Berlin Olympics, of George Bellows’ painting of Dempsey knocking Firpo out of the ring. The boxer in this show is still. The legendary photographer Gordon Parks reveals Muhammad Ali, the leading symbol of athletic protest, in a rare moment of stunning silence. The boxing champion is framed in a doorway, praying. Contrast that to the in-your-face fury of Michael Ray Charles’ “Yesterday.” A powerful black figure in a loin-cloth bursts through a jungle to slam-dunk his own head through what looks like basketball hoop of vines. A cameo of Abraham Lincoln looks on. Is the artist suggesting that the end of slavery is the beginning of March Madness? More subtle but no less troubling is Charles’ rendition of the face of O.J. -

Press Release ENG

SHARIF BEY EDDY KAMUANGA PAT PHILLIPS MICHAEL RAY CHARLES KATHIA ST HILAIRE 20th March – 8th May 2021 Zidoun-Bossuyt Gallery is pleased to present an exhibition of sculptures, paintings and works on paper by Sharif Bey, Eddy Kamunaga, Michael Ray Charles, Pat Phillips and Kathia St Hilaire. Sharif Bey “I was raised in an anti-imperialist household - that was the culture,” Sharif Bey explains, “a culture of asking, of questioning, of pushing back on the narratives that media has fed to us.” Over the past thirty years, Bey has channeled this impulse into his clay practice. Bey’s sculptures reference the visual heritage of Africa and Oceania, as well as present-day African American culture, exploring the significance of traditional beads and figurines through contemporary reinterpretations of these forms. He works primarily with ceramics, a medium historically used by communities to create both functional objects and objects of worship. Investigating the symbolic and formal properties of archetypal motifs, Bey questions how the meaning of icons transform across cultures and time. Bey does not shy away from stereotypical associations. Instead, he reappropriates and recontextualizes this imagery to challenge the cultural mainstream. For example, in the Protest Shields, the artist incorporates ceremonial elements with crowns of raised fists – another symbol whose meaning has continually shifted, from workers’ movements of the early twentieth century, to the Black Power movement of nineteen sixties and seventies, to today’s Black Lives Matter movement. Sharif Bey [b. 1974, Pittsburgh, PA] lives and works in Syracuse, NY, where in addition to this studio practice he is an associate professor in arts education and teaching and leadership in the College of Visual and Performing Arts and Syracuse University’s School of Education. -

Interpreting Art : Reflecting, Wondering, and Responding

E>»isa S' oc 3 Interpreting Art Interpreting Art Reflecting, Wondering, and Responding Terry Barrett The Ohio State University Boston Burr Ridge, IL Dubuque, IA Madison, Wl New York San Francisco St. Louis Bangkok Bogota Caracas Kuala Lumpur Lisbon London Madrid Mexico City Milan Montreal New Delhi Santiago Seoul Singapore Sydney Taipei Toronto McGraw-Hill Higher Education gg A Division of The McGraw-Hill Companies Interpreting Art: Reflecting, Wondering, and Responding Published by McGraw-Hill, an imprint of The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 1221 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020. Copyright ® 2003 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written consent of The McGraw- Hill Companies, Inc., including, but not limited to, in any network or other electronic storage or transmission, or broadcast for distance learning. This book is printed on acid-free paper. 34567890 DOC/DOC 0 9 8 7 6 5 4 ISBN 0-7674-1648-1 Publisher: Chris Freitag Sponsoring editor: Joe Hanson Marketing manager: Lisa Berry Production editor: David Sutton Senior production supervisor: Richard DeVitto Designer: Sharon Spurlock Photo researcher: Brian Pecko Art editor: Emma Ghiselli Compositor: ProGraphics Typeface: 10/13 Berkeley Old Style Medium Paper: 45# New Era Matte Printer and binder: RR Donnelley & Sons Because this page cannot legibly accommodate all the copyright notices, page 249 constitutes an extension of the copyright page. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Barrett, Terry Michael, 1945- Interpreting Art: reflecting, wondering, and responding / Terry Barrett, p. -

Diaspora/Strategies/Realities a Conference Paper on African

n.paradoxa online, issue 7 July 1998 Editor: Katy Deepwell n.paradoxa online issue no.7 July 1998 ISSN: 1462-0426 1 Published in English as an online edition by KT press, www.ktpress.co.uk, as issue 7, n.paradoxa: international feminist art journal http://www.ktpress.co.uk/pdf/nparadoxaissue7.pdf July 1998, republished in this form: January 2010 ISSN: 1462-0426 All articles are copyright to the author All reproduction & distribution rights reserved to n.paradoxa and KT press. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, including photocopying and recording, information storage or retrieval, without permission in writing from the editor of n.paradoxa. Views expressed in the online journal are those of the contributors and not necessarily those of the editor or publishers. Editor: [email protected] International Editorial Board: Hilary Robinson, Renee Baert, Janis Jefferies, Joanna Frueh, Hagiwara Hiroko, Olabisi Silva. www.ktpress.co.uk n.paradoxa online issue no.7 July 1998 ISSN: 1462-0426 2 List of Contents Pennina Barnett Materiality, Subjectivity & Abjection in the Work ofChohreh Feyzdjou, Nina Saunders and Cathy de Monchaux 4 Howardena Pindell Diaspora/Strategies/Realities 12 Jane Fletcher Uncanny Resemblances: The Uncanny Effect of Sally Mann's Immediate Family 27 Suzana Milevska Female Art Through the Looking Glass 38 Katy Deepwell Out of Sight / Out of Action 42 Diary of an Ageing Art Slut 46 n.paradoxa online issue no.7 July 1998 ISSN: 1462-0426 3 Diaspora/Realities/Strategies Howardena Pindell African-American artists in the diaspora face continuing cutbacks in American government funding of the arts due to conservative pressure in Congress, a situation which has led to the restriction and/ or curtailment of organisations serving African-American communities and the general public. -

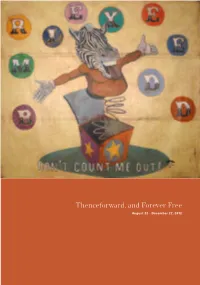

Thenceforward, and Forever Free August 22 - December 22, 2012 2

1 1 Thenceforward, and Forever Free August 22 - December 22, 2012 2 Cover image Michael Ray Charles American, b. 1967 (Forever Free) Mixed Breed, 1997 Acrylic latex, stain and copper penny on canvas tarp 99 x 111" Collection of Tony Shafrazi Gallery, New York 3 Thenceforward, and Forever Free August 22 - December 22, 2012 Thenceforward, and Forever Free is presented as part of Marquette University’s Freedom Project, a yearlong commemoration of the Sesquicentennial of the Civil War. The Project explores the many histories and meanings of emancipation and freedom in the United States and beyond. The exhibition features seven contemporary artists whose work deals with issues of race, gender, privilege, and identity, and more broadly conveys interpretations of the notion of freedom. Artists in Thenceforward are: Laylah Ali, Willie Birch, Michael Ray Charles, Gary Simmons, Elisabeth Subrin, Mark Wagner, and Kara Walker. Essayists for the exhibition catalogue are Dr. A. Kristen Foster, associate professor, Department of History, Marquette University, and Ms. Kali Murray, assistant professor, Marquette University Law School. Thenceforward, and Forever Free is sponsored in part by the Friends of the Haggerty, the Joan Pick Endowment Fund, the Marquette University Andrew W. Mellon Fund, a Marquette Excellence in Diversity Grant, the Martha and Ray Smith, Jr. Endowment Fund, the Nelson Goodman Endowment Fund, and the Wisconsin Arts Board with funds from the State of Wisconsin and the National Endowment for the Arts. 4 Art and the American Paradox A. Kristen Foster, Ph.D. Associate Professor Department of History Marquette University On December 1, 1862—before signing the Emancipation Proclamation, before the end of the Civil War, and before the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment—President Abraham Lincoln sent his Annual Message to Congress. -

“Details That Matter” in the Appropriated Works of Las Meninas

CRAE - RCÉA 23 2010 (37) 23-36 Abstracts/Résumés pp. xv-xx Finding the “Details that Matter” in the Appropriated Works of Las Meninas Linda Apps Simon Fraser University Carolyn Mamchur Simon Fraser University Artists are constantly in a state of selecting. Selecting – to shape, to clarify, to discover, to make visible. A continuous flow of decisions must be made about inclusion and exclu- sion rendered simply as what to introduce, what to keep, and what to omit. Descriptively capturing what one wants to say requires an attentive and refined focus. The gathering and culling of details is a delicate process that results in the calci- fication of an idea. Researcher and educator Murray (1968) describes this selec- tion process in the art of writing as the searching for specifics. Strunk and White (2000) refer to it more precisely as finding the “details that matter” (p. 21). In visual art, this selection pro- cess is where the artist sifts through her physical and concep- tual toolbox to answer the nagging questions: Is this the direc- tion in which I want to take my subject? How does this colour, this line, or this object work when I position it here? Does it enhance? Does it disrupt? Does it do the job…of enhancing or disrupting? In the moment of creating, decisions may ap- pear to be made simply and/or spontaneously. However, the © 2010 CRAE - RCÉA & AUTHORS/AUTEURS Body_Layout_CRAE 37.indd 23 8/4/10 12:16:10 PM 24 Linda Apps and Carolyn Mamchur complexity of these acts in the excavation and rendering of a topic are rarely simple or spontaneous. -

Constructions of Black Identity in the Work of Glenn Ligon and Kara Walker Shadé R

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Theses, Dissertations, and Student Creative Activity, Art, Art History and Design, School of School of Art, Art History and Design Spring 5-2014 Constructions of Black Identity in the Work of Glenn Ligon and Kara Walker Shadé R. Ayorinde University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/artstudents Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, Contemporary Art Commons, and the Theory and Criticism Commons Ayorinde, Shadé R., "Constructions of Black Identity in the Work of Glenn Ligon and Kara Walker" (2014). Theses, Dissertations, and Student Creative Activity, School of Art, Art History and Design. 52. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/artstudents/52 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art, Art History and Design, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations, and Student Creative Activity, School of Art, Art History and Design by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 1 CONSTRUCTIONS OF BLACK IDENTITY IN THE WORK OF GLENN LIGON AND KARA WALKER by Shadé R. Ayorinde A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Major: Art History Under the Supervision of Professor Marissa Vigneault Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2014 2 CONSTRUCTIONS OF BLACK IDENTITY IN THE WORK OF GLENN LIGON AND KARA WALKER Shadé R. Ayorinde, M.A University of Nebraska, 2014 Advisor: Marissa Vigneault In this thesis I reference artworks and installations by Glenn Ligon and Kara Walker, as well as contemporary mass media images, to offer a reading of various constructions of black identity in the 1990s and into the 21st century. -

Theuniversity

0073040572 NON-PROFIT ORG. U.S. POSTAGE PAID PERMIT NO. 5910 THE U NIVER SI T Y UNIVERSITY ADVANCEMENT HOUSTON, TEXAS 306 McELHINNEY HALL HOUSTON, TEXAS 77204-5035 OF SPRING 2010 HOUSTON Magazine CHANGE SERVICE REQUESTED 2010ARTSCALENDAR SCHOOL OF THEATRE & DANCE MOORES SCHOOL OF MUSIC April 16–18, 22–25: Dangerous Liaisons April 19: Percussion Ensembles April 30–May 2: Spring Dance Concert April 21: Jazz Orchestra /Jazz Ensemble April 23–25: Symphonic Band/Symphonic Winds SCHOOL OF ART April 24: Choral Artists Through April 24: 2010 Masters April 25: Wind Ensemble Thesis Exhibition April 30: Symphony Orchestra June 12, 19, 26, July 3: Texas Music BLAFFER GALLERY Festival Orchestra May 14–July 31: Tomás Saraceno: June 8, 15, 22, 29: Festival Artist Lighter Than Air Exhibition Series Concerts (May 13: Opening Reception) New Frontier of Pride From Past to Present, the Cougar Legacy Endures • UH Inspiration • UH Motivation “II viaggio a Reims” | Moores Opera House • UH Determination Tell us what you think: www.uh.edu/magazine At The University of Houston Magazine, our goal is to create a publication UH RECEIVES $3.5 MILLION GRANT FOR APPLIED RESEARCH HUB p. 4 you’ll be proud to receive, read and share with others. Your involvement as an engaged reader is critical to our success. As we strive to continue to improve the magazine, we want to hear from you. Please help us by going online at www.uh.edu/survey to take a brief survey about your thoughts on The UH Magazine. We want to know whether you prefer the print or the online edition, what sections you most enjoy, what sections you don’t prefer and suggested improvements for our online edition. -

NEWS RELEASE Dec. 17, 2013

NEWS RELEASE Dec. 17, 2013 FRED JONES JR. MUSEUM OF ART UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA - NORMAN CONTACT MICHAEL BENDURE, Director of Communication, 405-325-3178, [email protected] FAX: 405-325-7696 www.ou.edu/fjjma FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE WITH IMAGE FJJMA to Celebrate 100th Student Exhibition Jan. 17 NORMAN, OKLA. — January 2014 marks the 100th celebration of the annual University of Oklahoma School of Art and Art History Student Exhibition. The student show will go on display at the Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art Tuesday, Jan. 14. A complimentary, public opening reception is scheduled at 7 p.m. Friday, Jan. 17, followed by an awards ceremony at 8 p.m. The competitive, juried show is held each spring semester and highlights the diverse works of art created by OU School of Art and Art History students. “The annual student art exhibition at the University of Oklahoma is a historic tradition that actually outdates the museum,” said Mark White, the Eugene B. Adkins and Chief Curator and interim director at the Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art. “Over the years, the art museum’s permanent collection has added quality work from up-and-coming artists. We are excited to help the School of Art and Art History celebrate a century of recognizing the university’s best student artists.” Internationally noted artist and University of Texas at Austin art professor Michael Ray Charles recently was named the primary juror for the centennial show. Last month, Charles filtered through hundreds of student submissions and selected 55 works for inclusion in the annual student exhibition. -

The Works of Faith Ringgold and Kara Walker Amy Bradshaw

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Honors Theses Student Research 2007 Refiguring history : the works of Faith Ringgold and Kara Walker Amy Bradshaw Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Bradshaw, Amy, "Refiguring history : the works of Faith Ringgold and Kara Walker" (2007). Honors Theses. 1354. https://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses/1354 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Vo""-f i" ~CC\._~ .S~ "..1.J UNIVERSITYiliiifilif s I\IIIL201192 3256 Refiguring History: The Works of Faith Ringgold and Kara Walker by Amy Bradshaw A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies University of Richmond May2007 Acknowledgements I would like to thank the Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies Department at the University of Richmond and Dr. Dorothy Holland, WGSS Coordinator. I would also like to thank my primary advisor, Dr. Mia Reinoso-Genoni, for her endless advice and comedic relief. I especially thank The Common Ground Initiative and Glyn Hughes, for their interest and support of this project. I would also like to thank my friends and family for their support during this project. Method In this thesis, I seek to investigate various elements that the works of Faith Ringgo ld (b 1930) and Kara Walker (b 1969) have in common as well as explore the differences. -

Bowden's Anger Is Delicious

| Index by Title | Acting Egyptian, contents Gitre .................. 106 The Adorned Body, Books for the Trade ...................... 2–69 Carter, Houston & Rossi... 94–95 Books for Scholars . 70–109 Agent of Change, Orozco .................. 77 Sales Information ...........................110 All I Ever Wanted, Valentine ............... 8–11 Sales Representatives ............ 110–112 All New, All Different?, Austin & Hamilton . 98 American Tacos, Ralat ................ 20–23 university of texas press America’s Most Alarming Writer, Bowden .............. 40–43 Exile and the Nation, My Shadow Is My Skin, ................ Whitney & Emery ......... 108 The Ancient Roman Afterlife, Marashi 105 King .................. 101 The Eye of the Mammoth, No Way but to Fight, ................. Smith................ 34–35 Bea Nettles, Harrigan 7 Allen & Lahs-Gonzales ... 46–49 The Florentine Codex, Out of the Shadow, ...... Gibbings & Vrana .......... 93 Big Wonderful Thing, Peterson & Terraciano, 81 Harrigan ............... 4–6 Glitter Up the Dark, Pictured Politics, ............... Engel ................ 82–83 Biscuits, the Dole, and Nodding Geffen 28–29 Donkeys, Guitar King, Quinceañera Style, Brown & Ozanne........ 64–65 Dann ................ 24–27 González ................ 79 Border Citizens, Haiku History, Radical Cartographies, Meeks................... 73 Brands............... 32–33 Sletto, Wagner, Bryan & Hale .. 85 Border Land, Border Water, Improbable Metropolis, Reading, Writing, and Alvarez.................. 72 Bradley .............. 66–69