Constructions of Black Identity in the Work of Glenn Ligon and Kara Walker Shadé R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

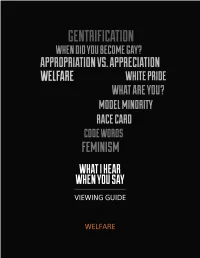

10-Welfare-Viewing Guide.Pdf

1 | AN INTRODUCTION TO WHAT I HEAR WHEN YOU SAY Deeply ingrained in human nature is a tendency to organize, classify, and categorize our complex world. Often, this is a good thing. This ability helps us make sense of our environment and navigate unfamiliar landscapes while keeping us from being overwhelmed by the constant stream of new information and experiences. When we apply this same impulse to social interactions, however, it can be, at best, reductive and, at worst, dangerous. Seeing each other through the lens of labels and stereotypes prevents us from making authentic connections and understanding each other’s experiences. Through the initiative, What I Hear When You Say ( WIHWYS ), we explore how words can both divide and unite us and learn more about the complex and everchanging ways that language shapes our expectations, opportunities, and social privilege. WIHWYS ’s interactive multimedia resources challenge what we think we know about race, class, gender, and identity, and provide a dynamic digital space where we can raise difficult questions, discuss new ideas, and share fresh perspectives. 1 | Introduction WELFARE I think welfare queen is an oxymoron. I can’t think of a situation where a queen would be on welfare. “ Jordan Temple, Comedian def•i•ni•tion a pejorative term used in the U.S. to refer to women who WELFARE QUEEN allegedly collect excessive welfare payments through fraud or noun manipulation. View the full episode about the term, Welfare Queen http://pbs.org/what-i-hear/web-series/welfare-queen/ A QUICK LOOK AT THE HISTORY OF U.S. -

© 2015 Kasey Lansberry All Rights Reserved

© 2015 KASEY LANSBERRY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED THE INTERSECTION OF GENDER, RACE, AND PLACE IN WELFARE PARTICIPATION: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF WELFARE-TO-WORK PROGRAMS IN OHIO AND NORTH CAROLINA COUNTIES A Dissertation Presented to The Graduate Faculty at the University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Kasey D. Lansberry August, 2015 THE INTERSECTION OF GENDER, RACE, AND PLACE IN WELFARE PARTICIPATION: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF WELFARE-TO-WORK PROGRAMS IN OHIO AND NORTH CAROLINA COUNTIES Kasey Lansberry Dissertation Approved: Accepted: ________________________________ ____________________________________ Advisor Department Chair Dr. Tiffany Taylor Dr. Matthew Lee ________________________________ ____________________________________ Co-Advisor or Faculty Reader Dean of the College Dr. Kathryn Feltey Dr. Chand Midha ________________________________ ____________________________________ Committee Member Interim Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Adrianne Frech Dr. Chand Midha ________________________________ ____________________________________ Committee Member Date Dr. Janette Dill ________________________________ Committee Member Dr. Nicole Rousseau ________________________________ Committee Member Dr. Pamela Schulze ii ABSTRACT Welfare participation has been a longstanding issue of public debate for over the past 50 years, however participation remains largely understudied in welfare literature. Various public policies, racial discrimination, the war on poverty, fictitious political depictions of the “welfare queen”, and a call for more stringent eligibility requirements all led up to the passage of welfare reform in the 1990s creating the new Temporary Aid for Needy Families (TANF) program. Under the new welfare program, work requirements and time limits narrowed the field of eligibility. The purpose of this research is to examine the factors that influence US welfare participation rates among the eligible poor in 2010. -

New Work: Glenn Ligon

- 1 glenn ligon: new work SAN FRANCISCO MUSEUM OF MODERN ART Glenn Ligon: New Work is a thought-proYoking, three part rumination on self-por traiture and the individual in relationship to collective hi,tories and notions of group identity. The first gallery of the show features four large, silkscreened paint ings based on news photos documenting the 1995 Million Man March. The next gallery contains a number of self-portraits of the artist himself, also silkscreened onto canvas, constituting a complement and counterpart to the images of the march. The final component is a collection of news clippings, test photos, journal notes, and other documents Ligon accumulated while creating the exhibition as a whole. This material will be archived permanently at the Gay and Lesbian Historical Society of Northern California and is on view there in conjunction with the show. Iigon considers these three components of the exhibition to be distinct and separate bodies of work, ret they arc also clearly related. Each element is a way of reflecting, both conceptually and visually, on ways that images of the self and the group are con structed and deployed, and to what ends. 'J he two bodies of imagery on view at SFMOMA stand in sharp contrast to one another: on one side, immense pictures of the Million Man March, showing African-American men joined together in an impressive show of unity and strength; on the other, a clinically spare series of unemotional head-shots of an individual man. The paintings derived from news photographs feature a largely undifferentiat ed sea of humanity and suggest themes long associated with photographs of demon strations: political struggle, adivbm, and protest. -

Celebrity and Race in Obama's America. London

Cashmore, Ellis. "To be spoken for, rather than with." Beyond Black: Celebrity and Race in Obama’s America. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2012. 125–135. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 29 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781780931500.ch-011>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 29 September 2021, 05:30 UTC. Copyright © Ellis Cashmore 2012. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 11 To be spoken for, rather than with ‘“I’m not going to put a label on it,” said Halle Berry about something everyone had grown accustomed to labeling. And with that short declaration she made herself arguably the most engaging black celebrity.’ uperheroes are a dime a dozen, or, if you prefer, ten a penny, on Planet SAmerica. Superman, Batman, Captain America, Green Lantern, Marvel Girl; I could fi ll the rest of this and the next page. The common denominator? They are all white. There are benevolent black superheroes, like Storm, played most famously in 2006 by Halle Berry (of whom more later) in X-Men: The Last Stand , and Frozone, voiced by Samuel L. Jackson in the 2004 animated fi lm The Incredibles. But they are a rarity. This is why Will Smith and Wesley Snipes are so unusual: they have both played superheroes – Smith the ham-fi sted boozer Hancock , and Snipes the vampire-human hybrid Blade . Pulling away from the parallel reality of superheroes, the two actors themselves offer case studies. -

Re-Presenting Black Masculinities in Ta-Nehisi Coates's

Re-Presenting Black Masculinities in Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me by Asmaa Aaouinti-Haris B.A. (Universitat de Barcelona) 2016 THESIS/CAPSTONE Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in HUMANITIES in the GRADUATE SCHOOL of HOOD COLLEGE April 2018 Accepted: ________________________ ________________________ Amy Gottfried, Ph.D. Corey Campion, Ph.D. Committee Member Program Advisor ________________________ Terry Anne Scott, Ph.D. Committee Member ________________________ April M. Boulton, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School ________________________ Hoda Zaki, Ph.D. Capstone Advisor STATEMENT OF USE AND COPYRIGHT WAIVER I do authorize Hood College to lend this Thesis (Capstone), or reproductions of it, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. ii CONTENTS STATEMENT OF USE AND COPYRIGHT WAIVER…………………………….ii ABSTRACT ...............................................................................................................iv DEDICATION………………………………………………………………………..v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………….....vi Chapter 1: Introduction…………………………………………………………….…2 Chapter 2: Black Male Stereotypes…………………………………………………12 Chapter 3: Boyhood…………………………………………………………………26 Chapter 4: Fatherhood……………………………………………………………....44 Chapter 5: Conclusion…………………………………………………………...….63 WORKS CITED…………………………………………………………………….69 iii ABSTRACT Ta-Nehisi Coates’s memoir and letter to his son Between the World and Me (2015)—published shortly after the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement—provides a rich and diverse representation of African American male life which is closely connected with contemporary United States society. This study explores how Coates represents and explains black manhood as well as how he defines his own identity as being excluded from United States society, yet as being central to the nation. Coates’s definition of masculinity is analyzed by focusing on his representations of boyhood and fatherhood. -

Silhouetted Stereotypes in the Art of Kara Walker

standards. They must give up their personal desires and Walker insists that her work “mimics the past, but it’s all live for the common good of the community. Hester about the present” (Tang 161). After her earning her strays from this conformity the first time when she has B.F.A. at Atlanta College of Art and further study at the sexual relations with her minister, a major violation of Rhode Island School of Design, Walker rose to community standards. She not only defiled herself, but prominence by winning the MacArthur Genius Grant in she defiled the leader of the community, and therefore, 1997 at the young age of 27 (Richardson 50). This the entire community. She does not conform again when prominent award poised Walker for great she bears the scarlet letter A with pride and dignity. The accomplishments, yet also exposed her to harsh community’s intention for punishing Hester is to force criticism from fellow African American women artists, her to fully repent. Hester seems to go through the such as Betye Saar, who launched a critical letterwriting motions of repentance. She stands on the scaffold, she campaign to boycott Walker’s work (Wall 277). Walker’s wears the letter A, and she lives on the outskirts of town. critics are quick to demonize aspects of her personal However, Hester’s “haughtiness,” “pride,” and “strong, life, like her marriage to a white European man, and calm, steadfastly enduring spirit” undermines the even her mental state, accusing her of mental distress community’s objective (Hawthorne, 213). -

Bibiliography

Parodies of Ownership: Hip-Hop Aesthetics and Intellectual Property Law Richard L. Schur http://www.press.umich.edu/titleDetailDesc.do?id=822512 The University of Michigan Press, 2009. Bibiliography A&M Records v. Napster. 2001. 239 F.3d 1004 (9th Cir.). Adler, Bill. 2006. “Who Shot Ya: A History of Hip Hop Photography.” Total Chaos: The Art and Aesthetics of Hip Hop. Ed. Jeff Chang. New York: Basic Books. 102–116. Alim, Salim. 2006. Roc the Mic Right: The Language of Hip Hop Culture. New York: Routledge. Alkalimat, Abdul. 2002a. Editor’s Notes. “Archive of Malcolm X For Sale.” By David Chang. February 20. www.h-net.org/~afro-am/. People can ‹nd the dis- cussion loss there H-Afro-Am. August 9, 2004. http://h-net.msu.edu/cgi- bin/logbrowse.pl?trx=vx&list=H-Afro-Am&month=0202&week=c&msg=c PR4wypSByppLKU61e5Diw&user=&pw=. Alkalimat, Abdul. 2002b. Editor’s Notes. “Archive of Malcolm X For Sale.” By Gerald Horne. February 20. H-Afro-Am. August 9, 2004. http://h- net.msu.edu/cgi-bin/logbrowse.pl?trx=vx&list=H-Afro-Am&month=0202& week=c&msg=JQnoJ7FS8tJmazqZ6J5S3Q&user=&pw=. Allen, Ernest, Jr. 2002. “Du Boisian Double Consciousness: The Unsustainable Ar- gument.” Massachusetts Review 43.2: 215–253. Alridge, Derrick. 2005. “From Civil Rights to Hip Hop: Toward a Nexus of Ideas.” Journal of African American History 90.3: 226–252. Ancient Egyptian Order of Nobles of the Mystic Shrine v. Michaux. 1929. 279 U.S. 737. Angelo, Bonnie. 1994. “The Pain of Being Black: An Interview with Toni Morri- son.” Conversations with Toni Morrison. -

Fort Gansevoort

FORT GANSEVOORT March Madness 5 Ninth Avenue, New York, NY, 10014 On View: Friday March 18 – May 1, 2016 Opening Reception: March 18, 6-9pm When sports and art collide with the impact of “March Madness,” a show of 28 artists opening March 18 at Fort Gansevoort, our games become metaphors, our heroes are transformed, even our golf bags reveal secrets. The artist’s eye finds the corruption, violence and racism behind the scoreboard, and the artist’s hand enhances the protest. To fans, “March Madness” refers to the hyped fun and games of the current national college basketball tournament. To Hank Willis Thomas and Adam Shopkorn, organizers of these 44 works, it reflects the classic spirit of Tommie Smith and John Carlos raising the black power salute at the 1968 Olympics, of Leni Riefenstahl’s film of the 1936 Berlin Olympics, of George Bellows’ painting of Dempsey knocking Firpo out of the ring. The boxer in this show is still. The legendary photographer Gordon Parks reveals Muhammad Ali, the leading symbol of athletic protest, in a rare moment of stunning silence. The boxing champion is framed in a doorway, praying. Contrast that to the in-your-face fury of Michael Ray Charles’ “Yesterday.” A powerful black figure in a loin-cloth bursts through a jungle to slam-dunk his own head through what looks like basketball hoop of vines. A cameo of Abraham Lincoln looks on. Is the artist suggesting that the end of slavery is the beginning of March Madness? More subtle but no less troubling is Charles’ rendition of the face of O.J. -

The Cultural Meaning of the "Welfare Queen": Using State Constitutions to Challenge Child Exclusion Provisions

THE CULTURAL MEANING OF THE "WELFARE QUEEN": USING STATE CONSTITUTIONS TO CHALLENGE CHILD EXCLUSION PROVISIONS RiSA E. KAuftIA.N* I. The Race Discrimination Underlying Child Exclusion Provisions .................................................... 304 A. The Welfare System's History of Discrimination Against African American Women ............................... 305 B. Images of the "Welfare Queen" ......................... 308 C. Illumination of History and Representation via the Cultural Meaning Test ................................... 312 I. The Insufficiency of Equal Protection Doctrine in Eliminating Race Discrimination in Welfare "Reform" Legislation ................................................... 314 III. The Use of State Constitutions for Challenging the Race Discrimination Inherent in Child Exclusion Provisions ...... 321 IV. Conclusion: The Advantages and Limitations of a Cultural Meaning Test ................................................ 326 The stereotype of the lazy, black welfare mother who "breeds children at the expense of the taxpayers in order to increase the amount of her welfare check"1 informs and justifies the ongoing welfare debate. This debate has led to the passage of recent federal welfare "reform" legislation eliminating the federal entitlement program of Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC).2 The debate now continues at the state * Law Clerk, the Honorable Ira DeMent, Middle District of Alabama; J.D., 1997, New York University; B.A., 1994, Talane University. I would like to thank, for their support and guidance, Paulette Caldwell, Martha F. Davis, Barbara Fedders, Lisa Kung, Anne Kysar, Jennie Pittman, Preston Pugh, Lynn Vogelstein, the staff of the N.Y.U. Review of Law and Social Change, and my family. 1. Dorothy Roberts, Punishing Drug Addicts Who Have Babies: Women of Color, Equality and Right to Privacy, 104 HARv. L. REv. 1419, 1443. -

Ice Cube Hello

Hello Ice Cube Look at these Niggaz With Attitudes Look at these Niggaz With Attitudes Look at these Niggaz With Attitudes Look at these Niggaz With Attitudes {Hello..} I started this gangsta shit And this the motherfuckin thanks I get? {Hello..} I started this gangsta shit And this the motherfuckin thanks I get? {Hello..} The motherfuckin world is a ghetto Full of magazines, full clips, and heavy metal When the smoke settle.. .. I'm just lookin for a big yellow; in six inch stilletos Dr. Dre {Hello..} perculatin keep em waitin While you sittin here hatin, yo' bitch is hyperventilatin' Hopin that we penetratin, you gets natin cause I never been to Satan, for hardcore administratin Gangbang affiliatin; MC Ren'll have you wildin off a zone and a whole half a gallon {Get to dialin..} 9 1 1 emergency {And you can tell em..} It's my son he's hurtin me {And he's a felon..} On parole for robbery Ain't no coppin a plea, ain't no stoppin a G I'm in the 6 you got to hop in the 3, company monopoly You handle shit sloppily I drop a ki properly They call me the Don Dada Pop a collar, drop a dollar if you hear me you can holla Even rottweilers, follow, the Impala Wanna talk about this concrete? Nigga I'm a scholar The incredible, hetero-sexual, credible Beg a hoe, let it go, dick ain't edible Nigga ain't federal, I plan shit while you hand picked motherfuckers givin up transcripts Look at these Niggaz With Attitudes Look at these Niggaz With Attitudes {Hello..} I started this gangsta shit And this the motherfuckin thanks I get? {Hello..} I started -

(2001) 96- 126 Gangsta Misogyny: a Content Analysis of the Portrayals of Violence Against Women in Rap Music, 1987-1993*

Copyright © 2001 Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture All rights reserved. ISSN 1070-8286 Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture, 8(2) (2001) 96- 126 GANGSTA MISOGYNY: A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF THE PORTRAYALS OF VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN IN RAP MUSIC, 1987-1993* by Edward G. Armstrong Murray State University ABSTRACT Gangsta rap music is often identified with violent and misogynist lyric portrayals. This article presents the results of a content analysis of gangsta rap music's violent and misogynist lyrics. The gangsta rap music domain is specified and the work of thirteen artists as presented in 490 songs is examined. A main finding is that 22% of gangsta rap music songs contain violent and misogynist lyrics. A deconstructive interpretation suggests that gangsta rap music is necessarily understood within a context of patriarchal hegemony. INTRODUCTION Theresa Martinez (1997) argues that rap music is a form of oppositional culture that offers a message of resistance, empowerment, and social critique. But this cogent and lyrical exposition intentionally avoids analysis of explicitly misogynist and sexist lyrics. The present study begins where Martinez leaves off: a content analysis of gangsta rap's lyrics and a classification of its violent and misogynist messages. First, the gangsta rap music domain is specified. Next, the prevalence and seriousness of overt episodes of violent and misogynist lyrics are documented. This involves the identification of attributes and the construction of meaning through the use of crime categories. Finally, a deconstructive interpretation is offered in which gangsta rap music's violent and misogynist lyrics are explicated in terms of the symbolic encoding of gender relationships. -

42 Artists Donate Works to Sotheby's Auction Benefitting the Studio Museum in Harlem

42 Artists Donate Works to Sotheby’s Auction Benefitting the Studio Museum in Harlem artnews.com/2018/05/03/42-artists-donate-works-sothebys-auction-benefitting-studio-museum-harlem Grace Halio May 3, 2018 Mark Bradford’s Speak, Birdman (2018) will be auctioned at Sotheby’s in a sale benefitting the Studio Museum in Harlem. COURTESY THE ARTIST AND HAUSER & WIRTH Sotheby’s has revealed the 42 artists whose works will be on offer at its sale “Creating Space: Artists for The Studio Museum in Harlem: An Auction to Benefit the Museum’s New Building.” Among the pieces at auction will be paintings by Mark Bradford, Julie Mehretu, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Glenn Ligon, and Njideka Akunyili Crosby, all of which will hit the block during Sotheby’s contemporary art evening sale and day sales in New York, on May 16 and 17, respectively. The sale’s proceeds will support the construction of the Studio Museum’s new building on 125th Street, the first space specifically developed to meet the institution’s needs. Designed by David Adjaye, of the firm Adjaye Associates, and Cooper Robertson, the new building will provide both indoor and outdoor exhibition space, an education center geared toward deeper community engagement, a public hall, and a roof terrace. “Artists are at the heart of everything the Studio Museum has done for the past fifty years— from our foundational Artist-in-Residence program to creating impactful exhibitions of artists of African descent at every stage in their careers,” Thelma Golden, the museum’s director and chief curator, said in a statement.