“It's Gonna Be Some Drama!”: a Content Analytical Study Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sunday Morning Grid 8/13/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

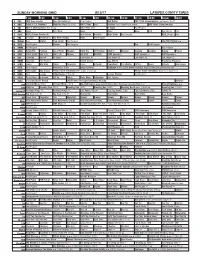

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 8/13/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Bull Riding 2017 PGA Championship Final Round. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Triathlon From Kailua-Kona, Hawaii. IAAF World Championships 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Invitation to Fox News Sunday News Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program The Pink Panther ›› 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program The Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking Cooking Baking Project 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bali (TVG) Bali (TVG) Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ KCET Special Å KCET Special Å KCET Special Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Central Liga MX (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Recuerda y Gana Juego Estrellas Gladiator ››› (2000, Drama Histórico) Russell Crowe, Joaquin Phoenix. -

BET Networks Delivers More African Americans Each Week Than Any Other Cable Network

BET Networks Delivers More African Americans Each Week Than Any Other Cable Network BET.com is a Multi-Platform Mega Star, Setting Trends Worldwide with over 6 Billion Multi-Screen Fan Impressions BET Networks Announces More Hours of Original Programming Than Ever Before Centric, the First Network Designed for Black Women, is One of the Fastest Growing Ad - Supported Cable Networks among Women NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- BET Networks announced its upcoming programming schedule for BET and Centric at its annual Upfront presentation. BET Networks' 2015 slate features more original programming hours than ever before in the history of the network, anchored by high quality scripted and reality shows, star studded tentpoles and original movies that reflect and celebrate the lives of African American adults. BET Networks is not just the #1 network for African Americans, it's an experience across every screen, delivering more African Americans each week than any other cable network. African American viewers continue to seek BET first and it consistently ranks as a top 20 network among total audiences. "Black consumers experience BET Networks differently than any other network because of our 35 years of history, tremendous experience and insights. We continue to give our viewers what they want - high quality content that respects, reflects and elevates them." said Debra Lee, Chairman and CEO, BET Networks. "With more hours of original programming than ever before, our new shows coupled with our returning hits like "Being Mary Jane" and "Nellyville" make our original slate stronger than ever." "Our brand has always been a trailblazer with our content trending, influencing and leading the culture. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

Feasibility Study of Marketing Channels in the Music Industry

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Drexel Libraries E-Repository and Archives Feasibility Study of Marketing Channels in the Music Industry A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Drexel University by Joseph Christopher Terry in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Television Management September 2012 © Copyright 2012 Joseph C. Terry. All Rights Reserved ii Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the guidance and the help of several individuals who in one way or another contributed and extended their valuable assistance in the preparation and completion of this study. First and foremost, this thesis would not have been possible without the guidance of Albert Tedesco, the Program Director of the Television Management Graduate Program. I would like to show my gratitude to Mary Cavallaro, Esq. for her support and guidance while writing the thesis. I wish to acknowledge Larry Rudolph, Adam Leber and Rebecca Lambrecht of Reign Deer Entertainment for showing me how the entertainment industry works on a worldwide scale. Finally, I want to thank my family and Kate for supporting me while writing this and giving me the encouragement to complete the thesis. Joseph C. Terry iii Table of Contents LIST OF TABLES .................................................................................................... v LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................. vi -

Friday Prime Time, April 17 4 P.M

April 17 - 23, 2009 SPANISH FORK CABLE GUIDE 9 Friday Prime Time, April 17 4 P.M. 4:30 5 P.M. 5:30 6 P.M. 6:30 7 P.M. 7:30 8 P.M. 8:30 9 P.M. 9:30 10 P.M. 10:30 11 P.M. 11:30 BASIC CABLE Oprah Winfrey Å 4 News (N) Å CBS Evening News (N) Å Entertainment Ghost Whisperer “Save Our Flashpoint “First in Line” ’ NUMB3RS “Jack of All Trades” News (N) Å (10:35) Late Show With David Late Late Show KUTV 2 News-Couric Tonight Souls” ’ Å 4 Å 4 ’ Å 4 Letterman (N) ’ 4 KJZZ 3The People’s Court (N) 4 The Insider 4 Frasier ’ 4 Friends ’ 4 Friends 5 Fortune Jeopardy! 3 Dr. Phil ’ Å 4 News (N) Å Scrubs ’ 5 Scrubs ’ 5 Entertain The Insider 4 The Ellen DeGeneres Show (N) News (N) World News- News (N) Two and a Half Wife Swap “Burroughs/Padovan- Supernanny “DeMello Family” 20/20 ’ Å 4 News (N) (10:35) Night- Access Holly- (11:36) Extra KTVX 4’ Å 3 Gibson Men 5 Hickman” (N) ’ 4 (N) ’ Å line (N) 3 wood (N) 4 (N) Å 4 News (N) Å News (N) Å News (N) Å NBC Nightly News (N) Å News (N) Å Howie Do It Howie Do It Dateline NBC A police of cer looks into the disappearance of a News (N) Å (10:35) The Tonight Show With Late Night- KSL 5 News (N) 3 (N) ’ Å (N) ’ Å Michigan woman. (N) ’ Å Jay Leno ’ Å 5 Jimmy Fallon TBS 6Raymond Friends ’ 5 Seinfeld ’ 4 Seinfeld ’ 4 Family Guy 5 Family Guy 5 ‘Happy Gilmore’ (PG-13, ’96) ›› Adam Sandler. -

Blacks Reveal TV Loyalty

Page 1 1 of 1 DOCUMENT Advertising Age November 18, 1991 Blacks reveal TV loyalty SECTION: MEDIA; Media Works; Tracking Shares; Pg. 28 LENGTH: 537 words While overall ratings for the Big 3 networks continue to decline, a BBDO Worldwide analysis of data from Nielsen Media Research shows that blacks in the U.S. are watching network TV in record numbers. "Television Viewing Among Blacks" shows that TV viewing within black households is 48% higher than all other households. In 1990, black households viewed an average 69.8 hours of TV a week. Non-black households watched an average 47.1 hours. The three highest-rated prime-time series among black audiences are "A Different World," "The Cosby Show" and "Fresh Prince of Bel Air," Nielsen said. All are on NBC and all feature blacks. "Advertisers and marketers are mainly concerned with age and income, and not race," said Doug Alligood, VP-special markets at BBDO, New York. "Advertisers and marketers target shows that have a broader appeal and can generate a large viewing audience." Mr. Alligood said this can have significant implications for general-market advertisers that also need to reach blacks. "If you are running a general ad campaign, you will underdeliver black consumers," he said. "If you can offset that delivery with those shows that they watch heavily, you will get a small composition vs. the overall audience." Hit shows -- such as ABC's "Roseanne" and CBS' "Murphy Brown" and "Designing Women" -- had lower ratings with black audiences than with the general population because "there is very little recognition that blacks exist" in those shows. -

Grown-Ish Introduction

THE REPRESENTATION OF FEMALE AFRICAN MONEJAH BLACK AMERICAN COLLEGE NATHANIEL FREDERICK, PHD, FACULTY STUDENTS ON MENTOR EMMANUEL NWACHUKWU, FACULTY TELEVISION: A MENTOR CONTENT ANALYSIS DEPARTMENT OF MASS COMMUNICATION OF A DIFFERENT WINTHROP UNIVERSITY WORLD AND GROWN-ISH INTRODUCTION Source: Wikipedia Commons Source: Fan Art TV •1987-1993 • 2018-present •Spin-off of The Cosby • College • Spin-off of Black-ish: experience of Show: black female the female black female daughter daughter (Denise African (Zoey Johnson) American lead attends California Huxtable) attends Hillman Predominantly Historically Black character University (PWI) White College (HBCU) College or University Institution Source: HBCU Buzz Source: TV Over Mind WHY IT MATTERS The representation of the female AA college student The representation of the college experience PWI non-minority students who have limited first-hand experience with AAs prior to/during college Who’s watching? What are they learning? High school students who have limited knowledge of what to expect in college LITERATURE REVIEW The Social Construction Sitcoms and African of the African American American Portrayal on Family on Television Television Television as a Vicarious Perceived Realism Experience THE SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION OF THE AFRICAN AMERICAN FAMILY ON TELEVISION: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE COSBY SHOW AND BLACK-ISH Differences in How AA family is Similarities in family Textual analysis on willingness to address constructed on demographics (well- The Cosby Show and certain topics such as television, evolved rounded, educated, Black-ish racial issues and over time suburban) stereotypes Stamps (2008) Source: Amazon Source: NPR SITCOMS AND THE AFRICAN AMERICAN PORTRAYAL ON TELEVISION Situational Comedy • Comical, yet expected to be Characters with Tells us how to run traits the audience moral our lives relate to • “The producers seem to have forgotten that you can’t raise a Berman moral issue and play with it— (1987) people expect you to solve it. -

TAKING a STAND Petty Said the Shop, Which Opened on Aug

MONDAY, AUGUST 21, 2017 Seaside mansion facing wrecking ball By Gayla Cawley Robert Corcoran, the own- It includes a large home/ Developer ITEM STAFF er of 133 Puritan Road, ac- mansion, carriage house quired the 1.06 acre proper- with residential space in- SWAMPSCOTT — The looking to ty in August 2014 for $1.785 owner of a Puritan Road side, tennis court and pool. build 16 property has proposed dem- million, according to land It abuts the Swampscott olition of the site’s existing records. The property is as- Harbor and includes a sea- condos in structures to make room for sessed at $2.943 million. wall, according to Peter the construction of 16 con- The property was built in Kane, director of community COURTESY PHOTO Swampscott dominiums or apartments, 1914 and is located at the development. This mansion at 133 Puritan Road could be razed to with an affordable housing intersection of Puritan Road construct three buildings with 16 condominiums. component. and Lincoln House Avenue. MANSION, A7 One’s trash is another’s treasure in Marblehead By Gayla Cawley ITEM STAFF MARBLEHEAD — After nearly three years, the Marblehead Swap Shop is open for busi- ness at the transfer station site on Wood n Terrace. Andrew Petty, director of public health, said the popular swap shop, or swap shed, is run by volunteers and has been closed for the past two and half years because of construction at the transfer station. The swap shed is open from May to October on Saturdays from 9 to 11:30 a.m. at 5 Wood- n Terrace, and allows residents to drop off usable items for other residents to take at no charge, according to the town website. -

Programming; Providing an Environment for the Growth and Education of Theatre Professionals, Audiences and the Community at Large

may 2012 NOBODY LOVES YOU A World Premiere Musical Comedy Welcome to The Old Globe began its journey with Itamar Moses and Gaby Alter’s Nobody Loves You in 2010, and we are thrilled to officially launch the piece here in its world premiere production. The Globe has a longstanding relationship with Itamar Moses. He was a Globe Playwright-in-Residence in 2007-2008 when we produced the world premieres of his plays Back Back Back and The Four of Us. Nobody Loves You is filled with the same HENRY DIROCCO HENRY whip-smart humor and insight that mark Itamar’s other works, here united with Gaby’s vibrant music and lyrics. Together they have created a piece that portrays, with a tremendous amount of humor and heart, the quest for love in a world in which romance is often commercialized. Just across Copley Plaza, the Globe is presenting another musical, the acclaimed The Scottsboro Boys, by musical theatre legends John Kander and Fred Ebb. We hope to see you back this summer for our 2012 Summer Shakespeare Festival. Under Shakespeare Festival Artistic Director Adrian Noble, this outdoor favorite features Richard III, As You Like It and Inherit the Wind in the Lowell Davies Festival Theatre. The summer season will also feature Michael Kramer’s Divine Rivalry as well as Yasmina Reza’s Tony Award-winning comedy God of Carnage. As always, we thank you for your support as we continue our mission to bring San Diego audiences the very best theatre, both classical and contemporary. Michael G. Murphy Managing Director Mission Statement The mission of The Old Globe is to preserve, strengthen, and advance American theatre by: Creating theatrical experiences of the highest professional standards; Producing and presenting works of exceptional merit, designed to reach current and future audiences; Ensuring diversity and balance in programming; Providing an environment for the growth and education of theatre professionals, audiences and the community at large. -

The Rhythm of College Life

The Rhythm of College Life For many students, going to college is filled with ambiguity and doubt. It may be their first time away from home for an extended period. There is powerful tension between their desire for more freedom and autonomy and their need for reassurance and support. Parents, too, have mixed emotions when their children leave home. They often feel a sense of loss accompanied by a sense of freedom. The house seems so quiet. At the same time, the house seems too quiet! Separation Anxiety People are more comfortable with the familiar. Your son or daughter has probably spent several years with the same friends from the same high school. The teachers are familiar, the school campus is familiar, and the town is familiar. College means finding a whole new set of friends, adapting to professors who do not treat them the way their high school teachers did, and navigating a campus where everything is not located in one building. Beginning a new adventure on campus at Tiffin University generates both excitement and anxiety. For students who adapt quickly, any apprehension is quickly overcome. For others, the transition may take a little longer and include some struggle with homesickness. Some students begin to feel anxious several weeks before they even leave home. Others seem OK at first only to find themselves feeling homesick later, perhaps after returning from Christmas break. Most often, though, the first few days or weeks are the most difficult. At TU, we help students feel accepted and secure by creating an environment in which they can function well and meet challenges successfully. -

* (Asterisk) in Google, 6 with Group Syntax, 215 in Name

CH27_228-236_Index.qxd 7/14/04 2:48 PM Page 229 INDEXINDEX * (asterisk) Applied Power, Principle of, brand names, 86–88 in Google, 6 102–106 Brooklyn Public Library, 119 with group syntax, 215 area codes, 169–170. See also browsers, 22–40 in name searches, 75 phone number searches bookmarklets with, 34–36 as wildcard, 6 art. See images gadgets for, 36–39 + (plus sign), 4–5. See also askanexpert.com, 93 iCab, 24 Boolean modifiers Ask Jeeves, 17–18 Internet Explorer, 23 – (minus sign), 4–5. See also for Kids, 210 listing, 25 Boolean modifiers toolbar, 32–33 Lynx, 24 | (pipe symbol), 5 associations Mozilla, 23 experts in, 91–93 Netscape, 23 finding, 92–93 Opera, 24 A audio, 154–163 plugins for, 27–29 finding, 159–160 Safari, 24–25 About.com, genealogy at, formats, 154–156 search toolbars with, 29–33 179–180 fun sites for, 162–163 security with, 25–26 address searches playing, 156–158 selecting, 25 driving directions and, 173 search engines/directories specialty toolbars with, 33 names in, 76–77 for, 160–162 speed optimization with, reverse lookups, 168–169 software sources, 158 26–27 229 for things/sites, 78 AU format, 155 turning off auto-password zip code helpers and, 172 reminders in, 26 AIFF format, 155 turning off Java in, 26 ALA Great Web Sites, 210 B turning off pop-ups in, 26 All Experts, 93–94 turning off scripting in, 25 AllPlaces, 134 Babelfish, 227 browser sniffer, 36–37 AlltheWeb, 160 BBB database, 195, 198 Bureau of Consumer Protection, almanacs, 186 Better Business Bureau, 195, 198 195 AltaVista, 148 biographical information, -

On the Fringe: a Practical Start-Up Guide to Creating, Assembling, and Evaluating a Fringe Festival in Portland, Oregon

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Oregon Scholars' Bank ON THE FRINGE: A PRACTICAL START-UP GUIDE TO CREATING, ASSEMBLING, AND EVALUATING A FRINGE FESTIVAL IN PORTLAND, OREGON By Chelsea Colette Bushnell A Master’s Project Presented to the Arts and Administration program of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Science in Arts and Administration November 2004 1 ON THE FRINGE: A Practical Start-Up Guide to Creating, Assembling, and Evaluating a Fringe Festival in Portland, Oregon Approved: _______________________________ Dr. Gaylene Carpenter Arts and Administration University of Oregon Date: ___________________ 2 © Chelsea Bushnell, 2004 Cover Image: Edinburgh Festival website, http://www.edfringe.com, November 12, 2004 3 Title: ON THE FRINGE: A PRACTICAL START-UP GUIDE TO CREATING, ASSEMBLING, AND EVALUATING A FRINGE FESTIVAL IN PORTLAND, OREGON Abstract The purpose of this study was to develop materials to facilitate the implementation of a seven- to-ten day Fringe Festival in Portland, Oregon or any similar metro area. By definition, a Fringe Festival is a non-profit organization of performers, producers, and managers dedicated to providing local, national, and international emerging artists a non-juried opportunity to present new works to arts-friendly audiences. All Fringe Festivals are committed to a common philosophy that promotes accessible, inexpensive, and fun performing arts attendance. For the purposes of this study, qualitative research methods, supported by action research and combined with fieldwork and participant observations, will be used to investigate, describe, and document what Fringe Festivals are all about.