Reality TV and Interpersonal Relationship Perceptions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

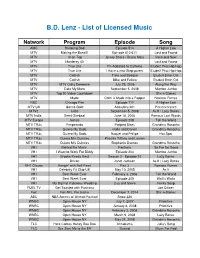

B.D. Lenz - List of Licensed Music

B.D. Lenz - List of Licensed Music Network Program Episode Song AMC Breaking Bad Episode 514 A Higher Law MTV Making the Band II Episode 610 611 Lost and Found MTV 10 on Top Jersey Shore / Bruno Mars Here and Now MTV Monterey 40 Lost and Found MTV True Life I'm Addicted to Caffeine Etude2 Phat Hip Hop MTV True Life I Have a new Step-parent Etude2 Phat Hip Hop MTV Catfish Trina and Scorpio Etude4 Bmin Ost MTV Catfish Mike and Felicia Etude4 Bmin Ost MTV MTV Oshq Deewane July 29, 2006 Along the Way MTV Date My Mom September 5, 2008 Mumbo Jumbo MTV Top 20 Video Countdown Stix-n-Stones MTV Made Colin is Made into a Rapper Noxious Fumes NBC Chicago Fire Episode 711 A Higher Law MTV UK Gonzo Gold Acoustics 201 Perserverance MTV2 Cribs September 5, 2008 As If / Lazy Bones MTV India Semi Girebaal June 18, 2006 Famous Last Words MTV Europe Gonzo Episode 208 Tell the World MTV TR3s Pimpeando Pimped Bikes Grandma Rosocha MTV TR3s Quiero My Boda Halle and Daneil Grandma Rosocha MTV TR3s Quiero My Boda Raquel and Philipe Hot Spot MTV TR3s Quiero Mis Quinces Priscilla Tiffany and Lauren MTV TR3s Quiero Mis Quinces Stephanie Duenas Grandma Rosocha VH1 Behind the Music Fantasia So Far So Good VH1 I Want to Work For Diddy Episode 204 Mumbo Jumbo VH1 Brooke Knows Best Season 2 - Episode 10 Lazy Bones VH1 Driven Janet Jackson As If / Lazy Bones VH1 Classic Hangin' with Neil Peart Part 3 Noxious Fumes VH1 Celebrity Fit Club UK May 10, 2005 As If VH1 Best Week Ever February 3, 2006 Tell the World VH1 Best Week Ever Episode 309 Walt's Waltz VH1 My Big Fat -

SCHOOL GARDENS.L

CHAPTEIl XI. SCHOOL GARDENS.l By E. G.L'G, 'I'riptis, Thuringia, Germany. C01drnts.-IIistorical Review-Sites and arrangement of Rchool gatdcns-s-Dilterent Rections of fkhool gardens-::\Ianagement-Instruction in School gardens-E\lucu- tional and Economic Significance of School gardens. 1. DISTOIlY. Rchool gardens, in the narrow sense of the term, are a very modern institution; but when considered as including all gardens serving the purpose of instruction, the expression ol Ben Akiba may be indorsed, "there is nothing new under the SUIl," for in a comprehensive sense, school gardens cease to be a modern institution. His- tory teaches that the great Persian King Cyrus the Elder ( 559-5~ B. C.) laid out the first school gardens in Persia, in which the sons of noblemen were instruct ·(1 ill hor- ticulture. King Solomon (1015 B. C.) likewise possessed extensive gardens ill which all kinds of plants were kept, probably for purposes of instruction as well as orna- ment, "from the cedar tree that is in Lebanon even unto the hyssop that springoth out of the wall." The botanical gardens of Italian and other univer -ities belong to school gardens in the broader acceptation of the term. The first to establish a garden of this kind was Gaspar de Gabriel, a wealthy Italian nobleman, who, in 1525 A. D., laid out the first one in Tuscany. Many Italian cities, Venice, Milan, and Naples followed this ex- ample. Pope Pius V (1566-1572) cstabli hed one in Bologna, and Duke Franci . of Tuscany (1574-1584) one in Florence. At that time, almost every important city in Italy possessed its botanical garden. -

On the Ball! One of the Most Recognizable Stars on the U.S

TVhome The Daily Home June 7 - 13, 2015 On the Ball! One of the most recognizable stars on the U.S. Women’s World Cup roster, Hope Solo tends the goal as the U.S. 000208858R1 Women’s National Team takes on Sweden in the “2015 FIFA Women’s World Cup,” airing Friday at 7 p.m. on FOX. The Future of Banking? We’ve Got A 167 Year Head Start. You can now deposit checks directly from your smartphone by using FNB’s Mobile App for iPhones and Android devices. No more hurrying to the bank; handle your deposits from virtually anywhere with the Mobile Remote Deposit option available in our Mobile App today. (256) 362-2334 | www.fnbtalladega.com Some products or services have a fee or require enrollment and approval. Some restrictions may apply. Please visit your nearest branch for details. 000209980r1 2 THE DAILY HOME / TV HOME Sun., June 7, 2015 — Sat., June 13, 2015 DISH AT&T CABLE DIRECTV CHARTER CHARTER PELL CITY PELL ANNISTON CABLE ONE CABLE TALLADEGA SYLACAUGA SPORTS BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM CONVERSION CABLE COOSA WBRC 6 6 7 7 6 6 6 6 AUTO RACING 5 p.m. ESPN2 2015 NCAA Baseball WBIQ 10 4 10 10 10 10 Championship Super Regionals: Drag Racing Site 7, Game 2 (Live) WCIQ 7 10 4 WVTM 13 13 5 5 13 13 13 13 Sunday Monday WTTO 21 8 9 9 8 21 21 21 8 p.m. ESPN2 Toyota NHRA Sum- 12 p.m. ESPN2 2015 NCAA Baseball WUOA 23 14 6 6 23 23 23 mernationals from Old Bridge Championship Super Regionals Township Race. -

Homeland Security Today Dayton, Ohio 11 August 2016

U.S.-Cuba Trade and Economic Council, Inc. New York, New York Telephone (917) 453-6726 • E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.cubatrade.org • Twitter: @CubaCouncil Facebook: www.facebook.com/uscubatradeandeconomiccouncil LinkedIn: www.linkedin.com/company/u-s--cuba-trade-and-economic-council-inc- Homeland Security Today Dayton, Ohio 11 August 2016 US to Deploy Federal Air Marshals on Cuba Flights By: Amanda Vicinanzo, Online Managing Editor The Transportation Security Administration (TSA) announced this week that the United States and Cuba have reached an agreement which will allow federal air marshals on board certain flights to and from Cuba. TSA released a statement on the decision at the request of the US-Cuba Trade and Economic Council. TSA explained that In-Flight Security Officers (IFSOs), also known as federal air marshals, play a crucial role in aviation security. The agency plans to continue to work with Cuba to expand the presence of IFSOs on flights to and from Cuba. “This agreement will strengthen both parties' aviation security efforts by furnishing a security presence on board certain passenger flights between the United States and The Republic of Cuba,” TSA said in the statement, adding, “IFSOs serve as an active last line of defense against terrorism and air piracy, and are an important part of a multi- layer strategy adopted by the US to thwart terrorism in the civil aviation sector.” Commenting on the announcement, Rep. Michael McCaul (R-Texas), Chairman of the House Committee on Homeland Security, warned that despite the presence of federal air marshals on flights between the two countries, Americans traveling to Cuba remain at risk. -

Sanibel Resident Killed by 12-Foot Alligator by Kevin Duffy Meisek Was Air-Lifted to Lee Memorial Tern

The islands' newspaper of record Andrew Congress and Kayia Weber Week of July 29 - August 4, 2004 SANIBEL & CAPTIVA, FLORIDA VOLUME 31, NUMBER 31 20 PAGES 75 CENTS Sanibel resident killed by 12-foot alligator By Kevin Duffy Meisek was air-lifted to Lee Memorial tern. Staff Writer shortly after police received a phone call Morse said that even a seemingly from a neighbor at 12:41 p.m. Wednesday, harmless activity, such as feeding ducks, A Sanibel resident attacked by an alli- informing them of the emergency. can present problems as well because gator on Wednesday has died, and city Officers discovered two persons in the ducks are part of an alligator's staple diet. officials say they wiil scrutinize existing water at the pond's edge attempting to "An alligator does not differentiate regulations to better safeguard people. assist Meisek, who was floating face up between the chef and the waiter, v/hose Janie Meisek, 54, a landscaper who and saying she was caught in vines. The being served or the meal," he said. "It rec- was dragged into a pond while tree-trim- officers, soon assisted by fire and EMS ognizes patterns of behavior, and if there ming behind a house at 3061 Poinciana personnel, took up the struggle, but could are ducks nearby, and you are feeding Circle, died at 9:16 a.m. Friday from com- not see the alligator despite Melsek's them, you are now part of the scenario. plications due to extensive injuries, offi- claims that it had her in it's jaws. -

COMING EVENTS Thursday, September 17, 2015

Page 8A East Oregonian COMING EVENTS Thursday, September 17, 2015 THURSDAY, SEPT. 17 S.W. Dorion Ave. Gym activities baked goods and plants, locally 2-mile and 5K run/walk. $5 entry VFW COWBOY BREAKFAST, and life skills for middle and high crafted jewelry and items for the fee, $10 shirt. Proceeds bene¿t the 6-10 a.m., Stillman Park, 413 S.E. school students. Free, but registra- home. EBT, debit and credit cards Morrow County cross country team. Byers Ave., Pendleton. Famous tion requested. (Danny Bane 541- welcome. (pendletonfarmersmar- DRIVE ONE 4 UR SCHOOL VFW pancakes, eggs, ham and 379-4250). ket.net). FUNDRAISER, 8 a.m. to 4 p.m., coffee or juice for $8 adults, $4 chil- THE ARC UMATILLA COUNTY VFW BINGO, doors open at 6 Hermiston High School, 600 S. dren under 12. BINGO, 6 p.m. doors open, bingo p.m., games start at 7 p.m., Herm- First St. Take a test drive in a new FREE ADMISSION AT HERI- starts at 7 p.m. 215 W. Orchard iston VFW, 45 W. Cherry St. Ford vehicle and help the high TAGE STATION MUSEUM, 10 a.m. Ave., Hermiston. (541-567-7615). THE EOSCENES, 6:30 p.m. school marching band attend the to 4 p.m., 108 S.W. Frazer Ave., FIDDLER’S NIGHT, 6:30-8:30 doors open, 7 p.m. concert, Pend- Holiday Bowl in December. Food Pendleton. Admission is free Mon- p.m., Hermiston Terrace Assisted leton Center for the Arts, 214 N. vendors and daycare will be avail- day-Thursday of Round-Up Week. -

Press Contacts for the Television Academy: 818-264

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Post-awards presentation (approximately 7:00PM, PDT) September 11, 2016 WINNERS OF THE 68th CREATIVE ARTS EMMY® AWARDS ANNOUNCED (Los Angeles, Calif. - September 11, 2016) The Television Academy tonight presented the second of 2016 Creative Arts Emmy® Awards ceremonies for programs and individual achievements at the Microsoft Theater in Los Angeles and honored variety, reality and documentary programs, as well as the many talented artists and craftspeople behind the scenes who create television excellence. Executive produced by Bob Bain, this year’s Creative Arts Awards featured an array of notable presenters, among them Derek and Julianne Hough, Heidi Klum, Jane Lynch, Ryan Seacrest, Gloria Steinem and Neil deGrasse Tyson. In recognition of its game-changing impact on the medium, American Idol received the prestigious 2016 Governors Award. The award was accepted by Idol creator Simon Fuller, FOX and FremantleMedia North America. The Governors Award recipient is chosen by the Television Academy’s board of governors and is bestowed upon an individual, organization or project for outstanding cumulative or singular achievement in the television industry. For more information, visit Emmys.com PRESS CONTACTS FOR THE TELEVISION ACADEMY: Jim Yeager breakwhitelight public relations [email protected] 818-264-6812 Stephanie Goodell breakwhitelight public relations [email protected] 818-462-1150 TELEVISION ACADEMY 2016 CREATIVE ARTS EMMY AWARDS – SUNDAY The awards for both ceremonies, as tabulated by the independent -

Implementing Screens Within Screens to Create Telepresence in Reality TV

Implementing screens within screens to create telepresence in reality TV Daniel Klug ∗ 1, Axel Schmidt ∗y 2 1 Institute for Media Studies, University of Basel – Suisse 2 Institute for the German Language – Allemagne Following Gumbrecht’s (2004) draft of a theory of presence the notion of presence aims at spatial relations: Something is present if it is tangible or ‘in actual range’ (Sch´’utz/Luckmann 1979). Concerning the social world, Goffman (1971) understands co-presence in a similar way, as the chance to get in direct contact with each other. For this, the possibility of mutually perceiving each other is a precondition and is in turn made possible by a shared location. Goffman’s concept of co-presence is bound to a shared here and now and thus is based on a notion of situation with place as its central dimension. Interaction as a basic mode of human exchange builds on situations and the possibility of mutual perception allowing so called perceived perceptions in particular (Hausendorf 2003) as the main mechanism of focused encounters. Media studies, however, proved that both the notion of situation as place and interaction as co-presence need to be extended as mediated contact creates new forms of situations and interactions. Especially Meyrowitz (1990) shows that the notion of situation has to be detached from the dimension of place and instead be redefined in terms of mediated contact. Therefore, the question ”who can hear me, who can see me?” is the basis for individual orientation and should guide the analysis of (inter)action. Although media enlarges the scope of perception in this way, it is not just a simple extension, but a trans- formation process in which the mediation itself plays a crucial role. -

1995-1996 Literary Magazine

á Shabash AMERICAN EMBASSY MIDDLE SCHOOL 1995-1996 LITERARY MAGAZINE Produced by Ms. Lundsteen’s English Class: Marco Acciarri Youn Joung Choi Bassem Amin Rohan Jetley Erin Brand Tara Lowen-Ault Grace Calma Daniel Luntzel Ajay Chand - Zoe Manickam With special thanks to Mrs. Kochar for her patience and guidance. Cover Design: Tara Lowen-Ault "" "7'_"'""’/Y"*"‘ ' F! f'\ O f O O f-\ ü Ö O o o o O O ____\. O o O . Q o ° '\ . '.-'.. n, . _',':'. '- -.'.` Q; Z / \ / The Handsome Toad A Trip Down Memory Lane Once upon a time a ugly princess was playing soccer with a solid gold ball in her garden. She slipped and the ball went flying up into the air When I was four, and landed into a nearby lake. “lt’s a throw in!” the umpire called out. My Dad was working in England, The princess went to get the ball but soon He was offered a job in Oman, realized that the ball had sunk. Then in spite of He went for the interview in the morning, herself she saw a toad swimming. I told him,“Daddy wear this tie.lt is fashion.” She said to the toad,”lf you go get my gold ball, He wore it. you can sleep in my bed tonight.” ' He got back in the evening. At first the toad did not think it was a good idea I asked “Daddy are we going to Oman?” but after all she was the princess so she could "Yes,” he said. execute him. So the toad agreed. -

In Honolulu's Christ Church in Kailua, Which Will Repeat Next Hemenway Theatre, UH Manoa Campus: Wed

5 The Fear Factor 8 Pritchett !ICalendar 13 Book Bonanza l!IStraight Dope Volume 3, Number 45, November 10, 1993 FREE Interview by JOHN WYTHE WHITE State Representative DaveHagino has spent 15 years fighting the system he's a partof- and theparty he belongs to. !JiORDERS BOOKS & MUSIC· BORDERS BOOKS & MUSIC· BORDERS BOOKS & MUSIC· BORDERS BOOKS & MUSIC· BORDERS BOOKS & MUSIC· BORDERS BOOKS & MUSIC· BORDERS BOOKS 8 ,,,, :,..: ;o 0 0 � �L � w ffi 8 Cl 0 ;,<; 0::: w 0 il,1.. � SELECTION: w 2 No Comparison 00 Cl 0::: i0 co co 0 ;o 0 -- -- co�:. 0 0 7' $�··· C nw oco ;o· · 0 m � co 0 0 w7' ::c: :::: C w 0:co 0 ;o 0 m � co 0 0 ci: � $ C w Borders® Books &Music. n ;o8 0 m The whole idea behind Finda book or music store the new Borders Books w;o co .- Borders Books & Music is to &Music. 0 with more titles and 0 w7' create an appealing place with Welcome to the new � $ we'll shop there. C more selection. So we brought Borders Books &Music. w () 100,000 in over book titles, more times the average store. Borders co 0 than 5 times the average bookstore. especially excels in classical and ;o It 0 CD m .r::;"' � OJ ;o What that means is that Borders jazz recordings. 0 E w (.) "' i co .r::; 'l' CD I 0 E 0 offersmore history, more com Borders also carries the area's (!) 0 """' 7' H-1 Fwy. w puters, more cooking. More of broadest selection of videotapes, � Waikele/Waipahu Exit 7 ::::: C everything, not just more copies including classic and foreign films. -

Ryan Dempsey SAG AFTRA Eligible (203)-233-0758

Ryan Dempsey SAG AFTRA Eligible (203)-233-0758 Height: 5’10 Weight: 190 Hair: Red Eyes: Hazel FILM: Party Boat Supporting SONY Pictures Studios/Mesquite Prod. /Dir: Dylan Kidd Summer Madness Supporting FIFTEEN Studios/Dir: Justin Poage Atomic Brain Invasion Supporting Scorpio Film Releasing/Dir: Richard Griffin TELEVISION / WEB SERIES: Homicide Hunter Guest-Star Jupiter Entertainment / Dir: Greg Francis Killer Couples Guest-Star Jupiter Entertainment / Dir: Brian Peery Office Secrets Co-Star Taylormade Film Company/ Dir: Tony F. Charles Mixed Emotions Co-Star E-Tre Productions/ Dir: Ernestine Johnson Room Raiders 2.0 Guest-Star MTV/Dir: Trip Swanhaus COMMERCIAL: Yard Force Principal Yard Force 3200 PSI Pressure Washer/ Dir: Nathan Shinholt Jay Morrison Academy Principal EZ Funding / Dir: Ernestine Johnson Marriott Featured Through The Madness TRAINING: Bill Walton Acting for the Camera Connecticut Eric E. Tonner Acting 1: Character Study Connecticut Eric E. Tonner Voice and Diction Connecticut Sal S. Trapani Acting 3: Period styles Connecticut Pamela D. McDaniel Acting 2: Scene Study Connecticut Pamela D. McDaniel Performance Technique Connecticut Louisa C. Burns Bisogno Screenwriting Workshop Connecticut Alessandro Folchitto/Gary Watson Tactical weapons training for film Georgia Gary Monroe Tactical Parkour for film Georgia Capt. Dale Dye Military Training for film Louisiana College Classes Western Connecticut State University, Connecticut SPECIAL SKILLS: Dialects (Irish, British, Southern, Boston), Tactical weapons training for film, Parkour with weapons, Stunt driving, Stand-Up Comedy, Improv, Bartending, Cooking, Good with Kids, Good with animals, Hand Gun experience, Assualt Rifle Experience, Shotgun Experience, Football, Baseball, Volleyball, Long-distance Runner, Belch on command, Wiggle Ears, Vibrate Eyeballs, Drivers License, Passport . -

Long Term Rental Sites & Docks

CEDAR COVE RESORT RENTAL TERMS & CONDITIONS 320 “Your Valley Vacation Village” a. A TRAILER (RV) when first placed on a seasonally rented site On Beautiful White Lake must be NEW, not more than 5 years old (based on availability of sites) & registered in the name of the person bringing it into 276 Full Service Seasonal Trailer Sites Cedar Cove. Tents, converted buses and truck campers are not to 24 Full Service and Pull-Thru Tourist Sites be placed on seasonally-rented sites. An RV must be maintained Year-round Cottages with Fireplaces in excellent condition. An RV with no rust, water leaks, wood rot, 130 Dock Slips exterior damage, or defective plumbing, appliances and fixtures is Rental Boats, Canoes, Kayaks, & Pedal Boats considered well maintained. Licensed Dining Lounge Three Volleyball Courts - Basketball Court b. All seasonal guests at Cedar Cove MUST have a permanent Ball Diamond - Four Horseshoe Pits address outside of the Resort unless otherwise approved by Cedar 100 Cedar Cove Road, RR 2 Two Children's Playgrounds Cove Resort. Child Friendly Sandy Beach White Lake, Ontario, Canada, K0A 3L0 c. All trailers in the Resort must be registered in the name of the Tel: 613 623 3133 - Fax: 613 623 5962 4,000 Foot Lakeside Walking Trail 6,000 Foot Forest Walking Trail guest leasing the site. Toll Free: 888 650 8572 d. Users of Resort facilities and equipment agree to HOLD Email: [email protected] CEDAR COVE ANNUAL EVENTS- HARMLESS the Owners & Staff of Cedar Cove for injury of any kind resulting from the use of the grounds or facilities of the During Peak Season (June 24 th – September 5nd 2016): www.cedarcove.ca Resort OR for loss or damage of personal property brought into In House "Family Bingo" - Saturdays the Resort or docked at a Resort dock.