Thenceforward, and Forever Free August 22 - December 22, 2012 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black History Month February 2020

BLACK HISTORY MONTH FEBRUARY 2020 LITERARY FINE ARTS MUSIC ARTS Esperanza Rising by Frida Kahlo Pam Munoz Ryan Frida Kahlo and Her (grades 3 - 8) Animalitos by Monica Brown and John Parra What Can a Citizen Do? by Dave Eggers and Shawn Harris (K-2) MATH & CULINARY HISTORY SCIENCE ARTS BLACK HISTORY MONTH FEBRUARY 2020 FINE ARTS Alma Thomas Jacob Lawrence Faith Ringgold Alma Thomas was an Faith Ringgold works in a Expressionist painter who variety of mediums, but is most famous for her is best-known for her brightly colored, often narrative quilts. Create a geometric abstract colorful picture, leaving paintings composed of 1 or 2 inches empty along small lines and dot-like the edge of your paper marks. on all four sides. Cut colorful cardstock or Using Q-Tips and primary Jacob Lawrence created construction paper into colors, create a painted works of "dynamic squares to add a "quilt" pattern in the style of Cubism" inspired by the trim border to your Thomas. shapes and colors of piece. Harlem. His artwork told stories of the African- American experience in the 20th century, which defines him as an artist of social realism, or artwork based on real, modern life. Using oil pastels and block shapes, create a picture from a day in your life at school. What details stand out? BLACK HISTORY MONTH FEBRUARY 2020 MUSIC Creating a Music important to blues music, and pop to create and often feature timeless radio hits. Map melancholy tales. Famous Famous Motown With your students, fill blues musicians include B.B. -

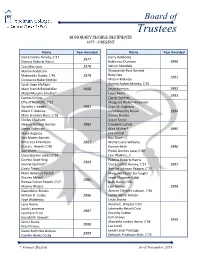

Honorary Degree Recipients 1977 – Present

Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Claire Collins Harvey, C‘37 Harry Belafonte 1977 Patricia Roberts Harris Katherine Dunham 1990 Toni Morrison 1978 Nelson Mandela Marian Anderson Marguerite Ross Barnett Ruby Dee Mattiwilda Dobbs, C‘46 1979 1991 Constance Baker Motley Miriam Makeba Sarah Sage McAlpin Audrey Forbes Manley, C‘55 Mary French Rockefeller 1980 Jesse Norman 1992 Mabel Murphy Smythe* Louis Rawls 1993 Cardiss Collins Oprah Winfrey Effie O’Neal Ellis, C‘33 Margaret Walker Alexander Dorothy I. Height 1981 Oran W. Eagleson Albert E. Manley Carol Moseley Braun 1994 Mary Brookins Ross, C‘28 Donna Shalala Shirley Chisholm Susan Taylor Eleanor Holmes Norton 1982 Elizabeth Catlett James Robinson Alice Walker* 1995 Maya Angelou Elie Wiesel Etta Moten Barnett Rita Dove Anne Cox Chambers 1983 Myrlie Evers-Williams Grace L. Hewell, C‘40 Damon Keith 1996 Sam Nunn Pinkie Gordon Lane, C‘49 Clara Stanton Jones, C‘34 Levi Watkins, Jr. Coretta Scott King Patricia Roberts Harris 1984 Jeanne Spurlock* Claire Collins Harvey, C’37 1997 Cicely Tyson Bernice Johnson Reagan, C‘70 Mary Hatwood Futrell Margaret Taylor Burroughs Charles Merrill Jewel Plummer Cobb 1985 Romae Turner Powell, C‘47 Ruth Davis, C‘66 Maxine Waters Lani Guinier 1998 Gwendolyn Brooks Alexine Clement Jackson, C‘56 William H. Cosby 1986 Jackie Joyner Kersee Faye Wattleton Louis Stokes Lena Horne Aurelia E. Brazeal, C‘65 Jacob Lawrence Johnnetta Betsch Cole 1987 Leontyne Price Dorothy Cotton Earl Graves Donald M. Stewart 1999 Selma Burke Marcelite Jordan Harris, C‘64 1988 Pearl Primus Lee Lorch Dame Ruth Nita Barrow Jewel Limar Prestage 1989 Camille Hanks Cosby Deborah Prothrow-Stith, C‘75 * Former Student As of November 2019 Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Max Cleland Herschelle Sullivan Challenor, C’61 Maxine D. -

Bibiliography

Parodies of Ownership: Hip-Hop Aesthetics and Intellectual Property Law Richard L. Schur http://www.press.umich.edu/titleDetailDesc.do?id=822512 The University of Michigan Press, 2009. Bibiliography A&M Records v. Napster. 2001. 239 F.3d 1004 (9th Cir.). Adler, Bill. 2006. “Who Shot Ya: A History of Hip Hop Photography.” Total Chaos: The Art and Aesthetics of Hip Hop. Ed. Jeff Chang. New York: Basic Books. 102–116. Alim, Salim. 2006. Roc the Mic Right: The Language of Hip Hop Culture. New York: Routledge. Alkalimat, Abdul. 2002a. Editor’s Notes. “Archive of Malcolm X For Sale.” By David Chang. February 20. www.h-net.org/~afro-am/. People can ‹nd the dis- cussion loss there H-Afro-Am. August 9, 2004. http://h-net.msu.edu/cgi- bin/logbrowse.pl?trx=vx&list=H-Afro-Am&month=0202&week=c&msg=c PR4wypSByppLKU61e5Diw&user=&pw=. Alkalimat, Abdul. 2002b. Editor’s Notes. “Archive of Malcolm X For Sale.” By Gerald Horne. February 20. H-Afro-Am. August 9, 2004. http://h- net.msu.edu/cgi-bin/logbrowse.pl?trx=vx&list=H-Afro-Am&month=0202& week=c&msg=JQnoJ7FS8tJmazqZ6J5S3Q&user=&pw=. Allen, Ernest, Jr. 2002. “Du Boisian Double Consciousness: The Unsustainable Ar- gument.” Massachusetts Review 43.2: 215–253. Alridge, Derrick. 2005. “From Civil Rights to Hip Hop: Toward a Nexus of Ideas.” Journal of African American History 90.3: 226–252. Ancient Egyptian Order of Nobles of the Mystic Shrine v. Michaux. 1929. 279 U.S. 737. Angelo, Bonnie. 1994. “The Pain of Being Black: An Interview with Toni Morri- son.” Conversations with Toni Morrison. -

Fort Gansevoort

FORT GANSEVOORT March Madness 5 Ninth Avenue, New York, NY, 10014 On View: Friday March 18 – May 1, 2016 Opening Reception: March 18, 6-9pm When sports and art collide with the impact of “March Madness,” a show of 28 artists opening March 18 at Fort Gansevoort, our games become metaphors, our heroes are transformed, even our golf bags reveal secrets. The artist’s eye finds the corruption, violence and racism behind the scoreboard, and the artist’s hand enhances the protest. To fans, “March Madness” refers to the hyped fun and games of the current national college basketball tournament. To Hank Willis Thomas and Adam Shopkorn, organizers of these 44 works, it reflects the classic spirit of Tommie Smith and John Carlos raising the black power salute at the 1968 Olympics, of Leni Riefenstahl’s film of the 1936 Berlin Olympics, of George Bellows’ painting of Dempsey knocking Firpo out of the ring. The boxer in this show is still. The legendary photographer Gordon Parks reveals Muhammad Ali, the leading symbol of athletic protest, in a rare moment of stunning silence. The boxing champion is framed in a doorway, praying. Contrast that to the in-your-face fury of Michael Ray Charles’ “Yesterday.” A powerful black figure in a loin-cloth bursts through a jungle to slam-dunk his own head through what looks like basketball hoop of vines. A cameo of Abraham Lincoln looks on. Is the artist suggesting that the end of slavery is the beginning of March Madness? More subtle but no less troubling is Charles’ rendition of the face of O.J. -

Media Release

MEDIA RELEASE The Studio Museum in Harlem 144 West 125th Street New York, NY 10027 studiomuseum.org/press Preview: Wednesday, November 13, 2013, 6 to 7pm Contact: Liz Gwinn, Communications Manager [email protected] 646.214.2142 This Fall, the Studio Museum presents The Shadows Took Shape, an exhibition with more than 60 works by 29 artists examining Afrofuturism from a global perspective Left: Cyrus Kabiru, Nairobian Baboon (from C-Stunners series), 2012. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Amunga Eshuchi. Right: The Otolith Group, Hydra Decapita (film still), 2010. Courtesy the artists New York, NY, July 9, 2013—This fall, The Studio Museum in Harlem is thrilled to present The Shadows Took Shape, a dynamic interdisciplinary exhibition exploring contemporary art through the lens of Afrofuturist aesthetics. Coined in 1994 by writer Mark Dery in his essay “Black to the Future,” the term “Afrofuturism” refers to a creative and intellectual genre that emerged as a strategy to explore science fiction, fantasy, magical realism and pan-Africanism. With roots in the avant-garde musical stylings of sonic innovator Sun Ra (born Herman Poole Blount, 1914–1993), Afrofuturism has been used by artists, writers and theorists as a way to prophesize the future, redefine the present and reconceptualize the past. The Shadows Took Shape will be one of the few major museum exhibitions to explore the ways in which this form of creative expression has been adopted internationally and highlight the range of work made over the past twenty-five years. On view at The Studio Museum in Harlem from November 14, 2013 to March 9, 2014, the exhibition draws its title from an obscure Sun Ra poem and a posthumously released series of recordings. -

Nytimes Black History Month Is a Good Excuse for Delving Into Our

Black History Month Is a Good Excuse for Delving Into Our Art An African-American studies professor suggests ways to mark the month, from David Driskell’s paintings and Dance Theater of Harlem’s streamed performances to the rollicking return of “Queen Sugar.” David Driskell’s “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” (1972), acrylic on canvas. Estate of David C. Driskell and DC Moore Gallery By Salamishah Tillet • Feb. 18, 2021 Black History Month feels more urgent this year. Its roots go back to 1926, when the historian Carter G. Woodson developed Negro History Week, near the February birthdays of both President Abraham Lincoln and the abolitionist Frederick Douglass, in the belief that new stories of Black life could counter old racist stereotypes. Now in this age of racial reckoning and social distancing, our need to connect with each other has never been greater. As a professor of African-American studies, I am increasingly animated by the work of teachers who have updated Woodson’s goal for the 21st century. Just this week, my 8- year-old daughter showed me a letter written by her entire 3rd-grade art class to Faith Ringgold, the 90-year-old African-American artist. And my son told me about a recent pre-K lesson on Ruby Bridges, the first African-American student who, at 6, integrated an elementary school in the South. Suddenly, the conversations my kids have at home with my husband and me are the ones they’re having in their classrooms. It's not just their history that belongs in all these spaces, but their knowledge, too. -

Direct Democracy, 2013, Curated By

DIRECT DEMOCRACY 1 2 DIRECT DEMOCRACY DIRECT DEMOCRACY Laylah Ali Hany Armanious Natalie Bookchin A Centre for Everything DAMP Destiny Deacon Alicia Frankovich Will French Gail Hastings Alex Martinis Roe Andrew McQualter John Miller Alex Monteith Raquel Ormella Mike Parr Simon Perry Carl Scrase Milica Tomić Kostis Velonis Jemima Wyman Curator: Geraldine Barlow Monash University Museum of Art | MUMA 26 April – 6 July 2013 7 Milica Tomic cover, back cover and pages 2-9 ‘One Day, Instead of One Night, a Burst of Machine-Gun Fire Will Flash, if Light Cannot Come Otherwise’ (Oskar Davico – fragment from a poem). Dedicated to the members of the Anarcho-Syndicalist Initiative – Belgrade, 3 September 2009 2009 8 9 10 11 12 13 John Miller pages 10-15 Tour scrums: Protesting black and blue 2007 14 15 16 17 18 19 Jemima Wyman page 16 Combat 02 2008 page 19 Combat 06 2008 page 20 Combat 08 2008 page 21 Combat drag 2008 20 21 22 23 24 25 Alicia Frankovich page 22 Slow dance 2011 page 23 Girl with a pomegranate 2012 pages 24-27 Bisons 2010 26 27 28 29 30 Kostis Velonis page 28 detail of hammers collected for Who might rebuild 2013 page 30 A sea of troubles (sail the red ship to the south) 2012 page 31 Untitled (life without tragedy) 2009 31 32 33 34 35 Hany Armanious pages 33, 35, 37 Mystery of the plinth 2010 36 37 38 39 40 A Centre for Everything (Will Foster & Gabrielle de Vietri) page 38 event documentation: Neighbourhood mapping, pesto and La révolution surréaliste 2013, top Show & tell, Ethiopian cuisine and verbal geography 2013, middle Bat talk, -

African American Creative Arts Dance, Literature, Music, Theater, and Visual Art from the Great Depression to Post-Civil Rights Movement of the 1960S

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 6, No. 2; February 2016 African American Creative Arts Dance, Literature, Music, Theater, and Visual Art From the Great Depression to Post-Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s Dr. Iola Thompson, Ed. D Medgar Evers College, CUNY 1650 Bedford Ave., Brooklyn, NY 11225 USA Abstract The African American creative arts of dance, music, literature, theater and visual art continued to evolve during the country’s Great Depression due to the Stock Market crash in 1929. Creative expression was based, in part, on the economic, political and social status of African Americans at the time. World War II had an indelible impact on African Americans when they saw that race greatly affected their treatment in the military while answering the patriotic call like white Americans. The Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s had the greatest influence on African American creative expression as they fought for racial equality and civil rights. Artistic aesthetics was based on the ideologies and experiences stemming from that period of political and social unrest. Keywords: African American, creative arts, Great Depression, WW II, Civil Rights Movement, 1960s Introduction African American creative arts went through several periods of transition since arriving on the American shores with enslaved Africans. After emancipation, African characteristics and elements began to change as the lifestyle of African Americans changed. The cultural, social, economic, and political vicissitudes caused the creative flow and productivity to change as well. The artistic community drew upon their experiences as dictated by various time periods, which also created their ideologies. During the Harlem Renaissance, African Americans experienced an explosive period of artistic creativity, where the previous article left off. -

Diversity in the Arts

Diversity In The Arts: The Past, Present, and Future of African American and Latino Museums, Dance Companies, and Theater Companies A Study by the DeVos Institute of Arts Management at the University of Maryland September 2015 Authors’ Note Introduction The DeVos Institute of Arts Management at the In 1999, Crossroads Theatre Company won the Tony Award University of Maryland has worked since its founding at the for Outstanding Regional Theatre in the United States, the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in 2001 to first African American organization to earn this distinction. address one aspect of America’s racial divide: the disparity The acclaimed theater, based in New Brunswick, New between arts organizations of color and mainstream arts Jersey, had established a strong national artistic reputation organizations. (Please see Appendix A for a list of African and stood as a central component of the city’s cultural American and Latino organizations with which the Institute revitalization. has collaborated.) Through this work, the DeVos Institute staff has developed a deep and abiding respect for the artistry, That same year, however, financial difficulties forced the passion, and dedication of the artists of color who have theater to cancel several performances because it could not created their own organizations. Our hope is that this project pay for sets, costumes, or actors.1 By the following year, the will initiate action to ensure that the diverse and glorious quilt theater had amassed $2 million in debt, and its major funders that is the American arts ecology will be maintained for future speculated in the press about the organization’s viability.2 generations. -

Press Release ENG

SHARIF BEY EDDY KAMUANGA PAT PHILLIPS MICHAEL RAY CHARLES KATHIA ST HILAIRE 20th March – 8th May 2021 Zidoun-Bossuyt Gallery is pleased to present an exhibition of sculptures, paintings and works on paper by Sharif Bey, Eddy Kamunaga, Michael Ray Charles, Pat Phillips and Kathia St Hilaire. Sharif Bey “I was raised in an anti-imperialist household - that was the culture,” Sharif Bey explains, “a culture of asking, of questioning, of pushing back on the narratives that media has fed to us.” Over the past thirty years, Bey has channeled this impulse into his clay practice. Bey’s sculptures reference the visual heritage of Africa and Oceania, as well as present-day African American culture, exploring the significance of traditional beads and figurines through contemporary reinterpretations of these forms. He works primarily with ceramics, a medium historically used by communities to create both functional objects and objects of worship. Investigating the symbolic and formal properties of archetypal motifs, Bey questions how the meaning of icons transform across cultures and time. Bey does not shy away from stereotypical associations. Instead, he reappropriates and recontextualizes this imagery to challenge the cultural mainstream. For example, in the Protest Shields, the artist incorporates ceremonial elements with crowns of raised fists – another symbol whose meaning has continually shifted, from workers’ movements of the early twentieth century, to the Black Power movement of nineteen sixties and seventies, to today’s Black Lives Matter movement. Sharif Bey [b. 1974, Pittsburgh, PA] lives and works in Syracuse, NY, where in addition to this studio practice he is an associate professor in arts education and teaching and leadership in the College of Visual and Performing Arts and Syracuse University’s School of Education. -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1993

L T 1 TO THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES: It is my special pleasure to transmit herewith the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts for the fiscal year 1993. The National Endowment for the Arts has awarded over 100,000 grants since 1965 for arts projects that touch every community in the Nation. Through its grants to individual artists, the agency has helped to launch and sustain the voice and grace of a generation--such as the brilliance of Rita Dove, now the U.S. Poet Laureate, or the daring of dancer Arthur Mitchell. Through its grants to art organizations, it has helped invigorate community arts centers and museums, preserve our folk heritage, and advance the perform ing, literary, and visual arts. Since its inception, the Arts Endowment has believed that all children should have an education in the arts. Over the past few years, the agency has worked hard to include the arts in our national education reform movement. Today, the arts are helping to lead the way in renewing American schools. I have seen first-hand the success story of this small agency. In my home State of Arkansas, the National Endowment for the Arts worked in partnership with the State arts agency and the private sector to bring artists into our schools, to help cities revive downtown centers, and to support opera and jazz, literature and music. All across the United States, the Endowment invests in our cultural institutions and artists. People in communities small and large in every State have greater opportunities to participate and enjoy the arts. -

Interpreting Art : Reflecting, Wondering, and Responding

E>»isa S' oc 3 Interpreting Art Interpreting Art Reflecting, Wondering, and Responding Terry Barrett The Ohio State University Boston Burr Ridge, IL Dubuque, IA Madison, Wl New York San Francisco St. Louis Bangkok Bogota Caracas Kuala Lumpur Lisbon London Madrid Mexico City Milan Montreal New Delhi Santiago Seoul Singapore Sydney Taipei Toronto McGraw-Hill Higher Education gg A Division of The McGraw-Hill Companies Interpreting Art: Reflecting, Wondering, and Responding Published by McGraw-Hill, an imprint of The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 1221 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020. Copyright ® 2003 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written consent of The McGraw- Hill Companies, Inc., including, but not limited to, in any network or other electronic storage or transmission, or broadcast for distance learning. This book is printed on acid-free paper. 34567890 DOC/DOC 0 9 8 7 6 5 4 ISBN 0-7674-1648-1 Publisher: Chris Freitag Sponsoring editor: Joe Hanson Marketing manager: Lisa Berry Production editor: David Sutton Senior production supervisor: Richard DeVitto Designer: Sharon Spurlock Photo researcher: Brian Pecko Art editor: Emma Ghiselli Compositor: ProGraphics Typeface: 10/13 Berkeley Old Style Medium Paper: 45# New Era Matte Printer and binder: RR Donnelley & Sons Because this page cannot legibly accommodate all the copyright notices, page 249 constitutes an extension of the copyright page. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Barrett, Terry Michael, 1945- Interpreting Art: reflecting, wondering, and responding / Terry Barrett, p.