1 Preserving the Legacy the Hotel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Fourteenth Colony: Florida and the American Revolution in the South

THE FOURTEENTH COLONY: FLORIDA AND THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION IN THE SOUTH By ROGER C. SMITH A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Roger C. Smith 2 To my mother, who generated my fascination for all things historical 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Jon Sensbach and Jessica Harland-Jacobs for their patience and edification throughout the entire writing process. I would also like to thank Ida Altman, Jack Davis, and Richmond Brown for holding my feet to the path and making me a better historian. I owe a special debt to Jim Cusack, John Nemmers, and the rest of the staff at the P.K. Yonge Library of Florida History and Special Collections at the University of Florida for introducing me to this topic and allowing me the freedom to haunt their facilities and guide me through so many stages of my research. I would be sorely remiss if I did not thank Steve Noll for his efforts in promoting the University of Florida’s history honors program, Phi Alpha Theta; without which I may never have met Jim Cusick. Most recently I have been humbled by the outpouring of appreciation and friendship from the wonderful people of St. Augustine, Florida, particularly the National Association of Colonial Dames, the ladies of the Women’s Exchange, and my colleagues at the St. Augustine Lighthouse and Museum and the First America Foundation, who have all become cherished advocates of this project. -

Black History Month February 2020

BLACK HISTORY MONTH FEBRUARY 2020 LITERARY FINE ARTS MUSIC ARTS Esperanza Rising by Frida Kahlo Pam Munoz Ryan Frida Kahlo and Her (grades 3 - 8) Animalitos by Monica Brown and John Parra What Can a Citizen Do? by Dave Eggers and Shawn Harris (K-2) MATH & CULINARY HISTORY SCIENCE ARTS BLACK HISTORY MONTH FEBRUARY 2020 FINE ARTS Alma Thomas Jacob Lawrence Faith Ringgold Alma Thomas was an Faith Ringgold works in a Expressionist painter who variety of mediums, but is most famous for her is best-known for her brightly colored, often narrative quilts. Create a geometric abstract colorful picture, leaving paintings composed of 1 or 2 inches empty along small lines and dot-like the edge of your paper marks. on all four sides. Cut colorful cardstock or Using Q-Tips and primary Jacob Lawrence created construction paper into colors, create a painted works of "dynamic squares to add a "quilt" pattern in the style of Cubism" inspired by the trim border to your Thomas. shapes and colors of piece. Harlem. His artwork told stories of the African- American experience in the 20th century, which defines him as an artist of social realism, or artwork based on real, modern life. Using oil pastels and block shapes, create a picture from a day in your life at school. What details stand out? BLACK HISTORY MONTH FEBRUARY 2020 MUSIC Creating a Music important to blues music, and pop to create and often feature timeless radio hits. Map melancholy tales. Famous Famous Motown With your students, fill blues musicians include B.B. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form 1

ntt NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections__________________ 1. Name__________________ historic Holy Assumption Orthodox Church_________________ and/or common Church of the Holv Assumption of the Virgin Mary 2. Location street & number Mission & Overland Streets not for publication city, town Kenai vicinity of state Alaska code county code 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public J£ _ occupied agriculture museum building(s) X private unoccupied commercial park _ structure both work in progress educational X private residence X site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment _X _ religious object in process _X _ yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation N.A. no military other: 4. Owner of Property name Alaska Diocese, Orthodox Church in America street & number Box 728 city, town Kodiak vicinity of state Alaska 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. U. S. Bureau of Land Management street & number 701 C Street city, town Anchorage state Alaska 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Alaska Heritage Resources title $urvev has this property been determined eligible? y yes __ no date June 16, 1972 federal _%_ state county local Office of History & Archeology, Alaska State Division of Parks depository for survey records pniirh 7nm (^ PnrHnya) Olympic Bldg.___________________ city, town Anchorage state Alaska 7. Description Condition Check one Check one __ excellent __ deteriorated __ unaltered _X_ original site _X_ good __ ruins _X_ altered __ moved date __ fair __ unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance See Continuation Sheet, NO. -

Numbered Panel 1

PRIDE 1A 1B 1C 1D 1E The African-American Baseball Experience Cuban Giants season ticket, 1887 A f r i c a n -American History Baseball History Courtesy of Larry Hogan Collection National Baseball Hall of Fame Library 1 8 4 5 KNICKERBOCKER RULES The Knickerbocker Base Ball Club establishes modern baseball’s rules. Black Teams Become Professional & 1 8 5 0 s PLANTATION BASEBALL The first African-American professional teams formed in As revealed by former slaves in testimony given to the Works Progress FINDING A WAY IN HARD TIMES 1860 – 1887 the 1880s. Among the earliest was the Cuban Giants, who Administration 80 years later, many slaves play baseball on plantations in the pre-Civil War South. played baseball by day for the wealthy white patrons of the Argyle Hotel on Long Island, New York. By night, they 1 8 5 7 1 8 5 7 Following the Civil War (1861-1865), were waiters in the hotel’s restaurant. Such teams became Integrated Ball in the 1800s DRED SCOTT V. SANDFORD DECISION NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BA S E BA L L PL AY E R S FO U N D E D lmost as soon as the game’s rules were codified, Americans attractions for a number of resort hotels, especially in The Supreme Court allows slave owners to reclaim slaves who An association of amateur clubs, primarily from the New York City area, organizes. R e c o n s t ruction was meant to establish Florida and Arkansas. This team, formed in 1885 by escaped to free states, stating slaves were property and not citizens. -

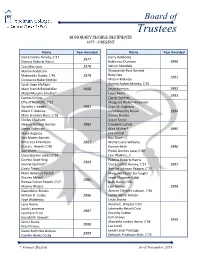

Honorary Degree Recipients 1977 – Present

Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Claire Collins Harvey, C‘37 Harry Belafonte 1977 Patricia Roberts Harris Katherine Dunham 1990 Toni Morrison 1978 Nelson Mandela Marian Anderson Marguerite Ross Barnett Ruby Dee Mattiwilda Dobbs, C‘46 1979 1991 Constance Baker Motley Miriam Makeba Sarah Sage McAlpin Audrey Forbes Manley, C‘55 Mary French Rockefeller 1980 Jesse Norman 1992 Mabel Murphy Smythe* Louis Rawls 1993 Cardiss Collins Oprah Winfrey Effie O’Neal Ellis, C‘33 Margaret Walker Alexander Dorothy I. Height 1981 Oran W. Eagleson Albert E. Manley Carol Moseley Braun 1994 Mary Brookins Ross, C‘28 Donna Shalala Shirley Chisholm Susan Taylor Eleanor Holmes Norton 1982 Elizabeth Catlett James Robinson Alice Walker* 1995 Maya Angelou Elie Wiesel Etta Moten Barnett Rita Dove Anne Cox Chambers 1983 Myrlie Evers-Williams Grace L. Hewell, C‘40 Damon Keith 1996 Sam Nunn Pinkie Gordon Lane, C‘49 Clara Stanton Jones, C‘34 Levi Watkins, Jr. Coretta Scott King Patricia Roberts Harris 1984 Jeanne Spurlock* Claire Collins Harvey, C’37 1997 Cicely Tyson Bernice Johnson Reagan, C‘70 Mary Hatwood Futrell Margaret Taylor Burroughs Charles Merrill Jewel Plummer Cobb 1985 Romae Turner Powell, C‘47 Ruth Davis, C‘66 Maxine Waters Lani Guinier 1998 Gwendolyn Brooks Alexine Clement Jackson, C‘56 William H. Cosby 1986 Jackie Joyner Kersee Faye Wattleton Louis Stokes Lena Horne Aurelia E. Brazeal, C‘65 Jacob Lawrence Johnnetta Betsch Cole 1987 Leontyne Price Dorothy Cotton Earl Graves Donald M. Stewart 1999 Selma Burke Marcelite Jordan Harris, C‘64 1988 Pearl Primus Lee Lorch Dame Ruth Nita Barrow Jewel Limar Prestage 1989 Camille Hanks Cosby Deborah Prothrow-Stith, C‘75 * Former Student As of November 2019 Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Max Cleland Herschelle Sullivan Challenor, C’61 Maxine D. -

1835. EXECUTIVE. *L POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT

1835. EXECUTIVE. *l POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT. Persons employed in the General Post Office, with the annual compensation of each. Where Compen Names. Offices. Born. sation. Dol. cts. Amos Kendall..., Postmaster General.... Mass. 6000 00 Charles K. Gardner Ass't P. M. Gen. 1st Div. N. Jersey250 0 00 SelahR. Hobbie.. Ass't P. M. Gen. 2d Div. N. York. 2500 00 P. S. Loughborough Chief Clerk Kentucky 1700 00 Robert Johnson. ., Accountant, 3d Division Penn 1400 00 CLERKS. Thomas B. Dyer... Principal Book Keeper Maryland 1400 00 Joseph W. Hand... Solicitor Conn 1400 00 John Suter Principal Pay Clerk. Maryland 1400 00 John McLeod Register's Office Scotland. 1200 00 William G. Eliot.. .Chie f Examiner Mass 1200 00 Michael T. Simpson Sup't Dead Letter OfficePen n 1200 00 David Saunders Chief Register Virginia.. 1200 00 Arthur Nelson Principal Clerk, N. Div.Marylan d 1200 00 Richard Dement Second Book Keeper.. do.. 1200 00 Josiah F.Caldwell.. Register's Office N. Jersey 1200 00 George L. Douglass Principal Clerk, S. Div.Kentucky -1200 00 Nicholas Tastet Bank Accountant Spain. 1200 00 Thomas Arbuckle.. Register's Office Ireland 1100 00 Samuel Fitzhugh.., do Maryland 1000 00 Wm. C,Lipscomb. do : for) Virginia. 1000 00 Thos. B. Addison. f Record Clerk con-> Maryland 1000 00 < routes and v....) Matthias Ross f. tracts, N. Div, N. Jersey1000 00 David Koones Dead Letter Office Maryland 1000 00 Presley Simpson... Examiner's Office Virginia- 1000 00 Grafton D. Hanson. Solicitor's Office.. Maryland 1000 00 Walter D. Addison. Recorder, Div. of Acc'ts do.. -

Historic Preservation in St.4Augustine

Historic Preservation in St.4Augustine Historic Preservation in St. Augustine The Ancient City By William R. Adams In the aftermath of St. Augustine’s fiery destruction at the hands of Governor The following essay was written by Dr. George Moore in 1702, the residents set about rebuilding the town. Little William Adams and published in the St. remained but the stone fortress that had sheltered them from the British and Augustine Historical Society’s publication the century-old plan for the colonial presidio, marked by the central plaza El Escribano. Permission to use within this and a rough pattern of crude streets that defined a narrow, rectangular grid document was granted by the author and the St. Augustine Historical Society. It was along the west bank of the Matanzas River, or what is now the Intracoastal composed in 2002 as a reflection of St. Waterway. In building anew, the Spanish residents employed materials more Augustine’s growth in the context of the durable than the wood and thatch which had defined the town the British preservation movement looking forward torched. to the 21st century. William R. (Bill) Adams St. Augustine is not just another city with a history. All cities boast a past. Nor received a Ph.D. in history at Florida State University and served as director of the is St. Augustine merely the nation’s oldest city. What it claims in the pages of Department of Heritage Tourism for the U. S. history is the distinction as the capital of Spain’s colonial empire in North City of St. -

PART 1 BDV25 TWO977-25 Task 2B Delive

EVALUATION OF SELF CONSOLIDATING CONCRETE AND CLASS IV CONCRETE FLOW IN DRILLED SHAFTS – PART 1 BDV25 TWO977-25 Task 2b Deliverable – Field Exploratory Evaluation of Existing Bridges with Drilled Shaft Foundations Submitted to The Florida Department of Transportation Research Center 605 Suwannee Street, MS30 Tallahassee, FL 32399 [email protected] Submitted by Sarah J. Mobley, P.E., Doctoral Student Kelly Costello, E.I., Doctoral Candidate and Principal Investigators Gray Mullins, Ph.D., P.E., Professor, PI Abla Zayed, Ph.D., Professor, Co-PI Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering University of South Florida 4202 E. Fowler Avenue, ENB 118 Tampa, FL 33620 (813) 974-5845 [email protected] January, 2017 to July, 2017 Preface This deliverable is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements set forth and agreed upon at the onset of the project and indicates a degree of completion. It also serves as an interim report of the research progress and findings as they pertain to the individual task-based goals that comprise the overall project scope. Herein, the FDOT project manager’s approval and guidance are sought regarding the applicability of the intermediate research findings and the subsequent research direction. The project tasks, as outlined in the scope of services, are presented below. The subject of the present report is highlighted in bold. Task 1. Literature Review (pages 3-90) Task 2a. Exploratory Evaluation of Previously Cast Lab Shaft Specimens (page 91-287) Task 2b. Field Exploratory Evaluation of Existing Bridges with Drilled Shaft Foundations Task 3. Corrosion Potential Evaluations Task 4. Porosity and Hydration Products Determinations Task 5. -

Imperial Standard: Imperial Oil, Exxon, and the Canadian Oil Industry from 1880

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2019-04 Imperial Standard: Imperial Oil, Exxon, and the Canadian Oil Industry from 1880 Taylor, Graham D. University of Calgary Press Taylor, G. D. (2019). Imperial Standard: Imperial Oil, Exxon, and the Canadian Oil Industry from 1880. "University of Calgary Press". http://hdl.handle.net/1880/110195 book https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca IMPERIAL STANDARD: Imperial Oil, Exxon, and the Canadian Oil Industry from 1880 Graham D. Taylor ISBN 978-1-77385-036-8 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence. -

The Breakers Palm Beach - More Than a Century of History

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Sara Flight (561) 659-8465 Bonnie Reuben (310) 248-3852 [email protected] [email protected] The Breakers Palm Beach - More than a Century of History PALM BEACH, FL – The Breakers’ celebrated history is a tribute to its founder, Henry Morrison Flagler, the man who transformed South Florida into a vacation destination for millions. Now into its second century, the resort not only enjoys national and international acclaim, but it continues to thrive under the ownership of Flagler’s heirs. Flagler’s Fortune and Florida’s East Coast When Henry Morrison Flagler first visited Florida in March 1878, he had accumulated a vast fortune with the Standard Oil Company (today Exxon Mobil) in Cleveland and New York as a longtime partner of John D. Rockefeller. In 1882, with the founding of the Standard Oil Trust, the then 52-year-old was earning and able to depend on an annual income of several millions from dividends. Impressed by Florida’s mild winter climate, Flagler decided to gradually withdraw from the company's day-to-day operations and turn his vision towards Florida and his new role of resort developer and railroad king. In 1885, Flagler acquired a site and began the construction of his first hotel in St. Augustine, Florida. Ever the entrepreneur, he continued to build south towards Palm Beach, buying and building Florida railroads and rapidly extending lines down the state's east coast. As the Florida East Coast Railroad opened the region to development and tourism, Flagler continued to acquire or construct resort hotels along the route. -

Annual Report of the Town Offices of Fairhaven, Massachusetts

Fairhaven High School showing addition and Henry Huttleston Rogers Monument Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 https ://arch i ve .org/detai Is/ann ual reportofto 1 978fai r ANNUAL REPORT of The Town Offices of Fairhaven, Massachusetts R. E. SMITH PRINTING CO.. INC. FALL RIVER. MASS. 1979 Town of Fairhaven -• Settled 1653 Incorporated 1812 Population 15,973 — 1975 State Census Twelfth Congressional District First Councillor District Bristol and Plymouth Senatorial District Tenth Bristol Representative District ELECTION OF OFFICERS First Monday in April 2 1 Fairhaven, Massachusetts General Information About the Town Located On the Shore of Buzzards Bay 56 Miles from Boston 1 Mile from New Bedford Registered Voters — 9072 Tax Rate -$211.00 Valuation - $28,563,670.00 Area — 7,497 Acres Miles of Shore Property — 21 Miles of Streets and Roads — Approximately 91 Number of Dwellings — 5310 Churches — 1 Public Schools — 8 Private Schools — 1 Banks — 6 Principal Industries Ship Building Fishing Industry Winches and Fishing Machinery Fish Freezing Tack and Nail Making Loam Crank Shafts Oil Refinery Diesel Engine Repairing Benefactions of the Late Henry Huttleston Rogers Millicent Library Town Hall High School Rogers School Unitarian Memorial Church Fairhaven Water Works Masonic Building Cushman Park 3 RETIRED POLICE CHIEF ALFRED RAPHAEL Served the T own of Fairhaven in the Police Department from 1941 until his retirement November 16, 1978 “A dedicated public seivant!” 4 Directory of Town Officers (Elective Officials Designated by Capital Letters) BOARD OF SELECTMEN WALTER SILVEIRA, Chairman Term Expires 1979 ROLAND N. SEGUIN Term Expires 1980 EVERETT J. MACOMBER, JR. Term Expires 1981 Alice S. -

Here Al Lang Stadium Become Lifelong Readers

RWTRCover.indd 1 4/30/12 4:15 PM Newspaper in Education The Tampa Bay Times Newspaper in Education (NIE) program is a With our baseball season in full swing, the Rays have teamed up with cooperative effort between schools the Tampa Bay Times Newspaper in Education program to create a and the Times to promote the lineup of free summer reading fun. Our goals are to encourage you use of newspapers in print and to read more this summer and to visit the library regularly before you electronic form as educational return to school this fall. If we succeed in our efforts, then you, too, resources. will succeed as part of our Read Your Way to the Ballpark program. By reading books this summer, elementary school students in grades Since the mid-1970s, NIE has provided schools with class sets three through five in Citrus, Hernando, Hillsborough, Manatee, Pasco of the Times, plus our award-winning original curriculum, at and Pinellas counties can circle the bases – first, second, third and no cost to teachers or schools. With ever-shrinking school home – and collect prizes as they go. Make it all the way around to budgets, the newspaper has become an invaluable tool to home and the ultimate reward is a ticket to see the red-hot Rays in teachers. In the Tampa Bay area, the Times provides more action at Tropicana Field this season. than 5 million free newspapers and electronic licenses for teachers to use in their classrooms every school year. Check out this insert and you’ll see what our players have to say about reading.