Historic Preservation in St.4Augustine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form 1

ntt NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections__________________ 1. Name__________________ historic Holy Assumption Orthodox Church_________________ and/or common Church of the Holv Assumption of the Virgin Mary 2. Location street & number Mission & Overland Streets not for publication city, town Kenai vicinity of state Alaska code county code 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public J£ _ occupied agriculture museum building(s) X private unoccupied commercial park _ structure both work in progress educational X private residence X site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment _X _ religious object in process _X _ yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation N.A. no military other: 4. Owner of Property name Alaska Diocese, Orthodox Church in America street & number Box 728 city, town Kodiak vicinity of state Alaska 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. U. S. Bureau of Land Management street & number 701 C Street city, town Anchorage state Alaska 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Alaska Heritage Resources title $urvev has this property been determined eligible? y yes __ no date June 16, 1972 federal _%_ state county local Office of History & Archeology, Alaska State Division of Parks depository for survey records pniirh 7nm (^ PnrHnya) Olympic Bldg.___________________ city, town Anchorage state Alaska 7. Description Condition Check one Check one __ excellent __ deteriorated __ unaltered _X_ original site _X_ good __ ruins _X_ altered __ moved date __ fair __ unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance See Continuation Sheet, NO. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB NO. 1024-0018 Expires 10-31-87 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS us« only ._ MAY 27 1986 National Register off Historic Places received ll0 Inventory Nomination Form date entered &> A// J^ See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name historic St. Augustine Historic District and or common 2. Location N/A street & number __ not for publication St. Augustine city, town vicinity of Florida state code 12 county St. Johns code 109 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use x district public occupied agriculture X museum building(s) private X unoccupied ^ commercial X .park structure X both work in progress X educational X . private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible X entertainment X religious object in process yes: restricted X government scientific being considered X yes: unrestricted industrial transportation x military . other: 4. Owner off Property name Multiple street & number N/A St. Augustine N/A city, town vicinity of state Florida 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. St. Johns County Courthouse street & number 95 Cordova Street city, town St. Augustine state Florida 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title St. Augustine Survey has this property been determined eligible? X yes __ no date 1978-1986 federal X state county local depository for survey records Florida Department of State; Hist. St. Augustine Preservation Bd, city, town Tallahassee and St. Augustine state Florida 7. Description Condition Check one Check one ___4;ejteeHent . deteriorated unaltered original site OOOu ruins altered moved date __ fair unexposed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance SUMMARY OF PRESENT AND ORIGINAL PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The revised St. -

1 Preserving the Legacy the Hotel

PRESERVING THE LEGACY THE HOTEL PONCE DE LEON AND FLAGLER COLLEGE By LESLEE F. KEYS A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2013 1 © 2013 Leslee F. Keys 2 To my maternal grandmother Lola Smith Oldham, independent, forthright and strong, who gave love, guidance and support to her eight grandchildren helping them to pursue their dreams. 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My sincere appreciation is extended to my supervisory committee for their energy, encouragement, and enthusiasm: from the College of Design, Construction and Planning, committee chair Christopher Silver, Ph.D., FAICP, Dean; committee co-chair Roy Eugene Graham, FAIA, Beinecke-Reeves Distinguished Professor; and Herschel Shepard, FAIA, Professor Emeritus, Department of Architecture. Also, thanks are extended to external committee members Kathleen Deagan, Ph.D., Distinguished Research Professor Emeritus of Anthropology, Florida Museum of Natural History and John Nemmers, Archivist, Smathers Libraries. Your support and encouragement inspired this effort. I am grateful to Flagler College and especially to William T. Abare, Jr., Ed.D., President, who championed my endeavor and aided me in this pursuit; to Michael Gallen, Library Director, who indulged my unusual schedule and persistent requests; and to Peggy Dyess, his Administrative Assistant, who graciously secured hundreds of resources for me and remained enthusiastic over my progress. Thank you to my family, who increased in number over the years of this project, were surprised, supportive, and sources of much-needed interruptions: Evan and Tiffany Machnic and precocious grandsons Payton and Camden; Ethan Machnic and Erica Seery; Lyndon Keys, Debbie Schmidt, and Ashley Keys. -

National Historic Landmark

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK. Theme: Architecture Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (Rev. 6-72) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Maryland COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Anne Arundel T "~ 0lt4VENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY "— ; ENTRY DATE (Type all entries complete applicable sections) London Town Publik House AND/OR HISTORIC: London Town Publik House STREET ANO NUMBER: End of London Town Road on South Bank of South River CITY OR TOWN: CONGRESSIONAL. DISTRICT: Vicinity of Annapolis 4th COUNT Y. Anne Mb CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) O District gg Building Public Public Acquisition: D Occupied Yes: i —i M . , I I Restricted Q Site Q Structure CD Private §2 In Process [_J Unoccupied ' — ' _, _ , Kl Unrestricted D Object { | Both [ | Being Considered | _| Preservation work in progress ' — ' PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) Agricultural 1 | Government [ | Park I I Transportation 1 1 Comments .Commercial 1~1 Industrial |~] Private Residence [D Other (Specify) Educational CD 'Military Q Religious Entertainment 83 Museum Q Scientific OWNER'S NAME: .-, - Lounty of Anne Arundel; administered by London Town Publik House Commission, Mr. Y. Kirlcpatrick Howat Chairman STREET AND NUMBER: -1 * w I*1 X Contee Farms CITY OR TOWN: STATE: CODF Edgewater Maryland 9/1 COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: Anne Arundel County Court House— Clerk of Circuit Court ArundelAnne COUNTY: STREET AND NUMBER: P.O. Box 71 C1 TY OR TOWN: STATE . CODE Annapolis Maryland 21404 24 T1TUE OF SURVEY: . • . Historic American Buildings Survey (8 photos) NUMBERENTRY 0 DATE OF SURVEY: 1936, 1937 XX Federal n Statc D County Q Loca 70 DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: -DZ cn Library of Congress/ Annex C STREET AND NUMBER: '•.... -

Front Cover: the Llambias House of St Augustine, Florida

The following article on the Llambias House National Historic Landmark was originally published in the Front Cover: The Llambias House of St Augustine, Southwestern Mission Research Center's (SMRC) Revista newsletter Volume 43, no. 160-161, 2009. Permission was granted by the President of SMRC by email on July 14, 2015 for a PDF copy to be made Florida. (Photo courtesy of Mark R. Barries.) of this article and posted on the National Park Service Electronic Library website, http://npshistory.com/. All rights reserved. 14 • News & Events SMRC REVISTA Figure 1. View of the front (north) and east elevations of the Llanibias House, looking southwest. (Photo courtesy of the St. Augustine Historical Society.) THE LLAMBIAS HOUSE: AN EXAMPLE OF SPANISH COLONIAL CARIBBEAN HOUSING IN THE SOUTHEASTERN UNITED STATES by MARK R. BARNES, PH.D. The Llambias House, located at 31 St. Francis Street in the south the edges of the house lot to enclose an interior courtyard. A ernmost section of the old Spanish colonial town of St. Augus notable feature of the St. Augustine Plan was a lack of direct tine, Florida, is a nationally significant example of the Spanish access to the interior of the residence from the street. Instead, colonial "St. Augustine Plan" of residential architecture that access was provided through a gate in the garden wall which led may be found throughout the Spanish Antilles (Figure 1). The to the courtyard, with two variations based on the manner of definitive work on this architectural style was produced in the access from the courtyard to the dwelling's interior: through a early 1960s by Albert Manucy and then expanded upon by other covered porch on the building's rear or through a covered loggia researchers. -

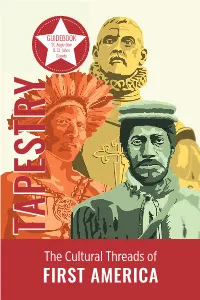

Tapestry Passport Program Created by the City of St

GUIDEBOOK St. Augustine & St. Johns County TAPESTRY TAPESTRY The Cultural Threads of FIRST AMERICA WELCOME TO GUIDEBOOK ST. AUGUSTINE! PROGRAM This program is designed to St. Augustine is America’s first connect you with important city, established in 1565. It is a city historic sites and programs in built on discovery, courage and St. Augustine and St. Johns enduring spirit; it is a city built by County. Use the map and pioneers, soldiers, artisans and destination descriptions to entrepreneurs. More than four navigate your way to the locations and a half centuries later, the (most are in walking distance). town and its people continue to symbolize the rich history and cultural diversity that makes St. Augustine unique. We welcome you to the Nation’s Oldest City and invite you to explore our rich history. Photo by Daniel J. Bagan The guidebook is divided into three historic periods designated by color. STARTING LOCATION 1 - Visitor Information Center DO FIRST AMERICA W 2 - Mission Nombre de Dios 3 - Fountain of Youth Archaeological Park NTO COLONIAL ST. AUGUSTINE 4 - City Gate and Cubo Defense Line W 5 - Castillo de San Marcos National Monument 6 - Tolomato Cemetery N 7 - Colonial Quarter DE 8 - St. Augustine Pirate & Treasure Museum 9 - St. Photios Greek Orthodox National Shrine S 10 - Peña-Peck House TIN 11 - Cathedral Basilica of St. Augustine 12 - Father Pedro Camps Monument 13 - Governor’s House Cultural Center & Museum A 14 - Plaza de la Constitución TION 15 - Spanish Constitution Monument 16 - Aviles Street 17 - Spanish Military Hospital Museum 18 - Ximenez-Fatio House Museum S 19 - Father Miguel O’Reilly House Museum 20 - St. -

ST. STEPHEN's EPISCOPAL CHURCH Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 ST. STEPHEN'S EPISCOPAL CHURCH Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: St. Stephen's Episcopal Church Other Name/Site Number: 2. LOCATION Street & Number: State 45 Not for publication: City/Town: St. Stephen's Vicinity:, State: SC County: Berkeley Code: 015 Zip Code: 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: x Building(s): _X_ Public-Local: __ District: _ Public-State: __ Site: _ Public-Federal: Structure: _ Object: _ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 1 _ buildings _ sites _ structures _ objects 1 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register:_ Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 ST. STEPHEN'S EPISCOPAL CHURCH Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal Agency and Bureau In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Resilient Herita Ge

TAYLOR ENGINEERING, INC. TAYLOR RESILIENT HERITAGE IN THE NATION’S OLDEST CITY CITY OF ST. AUGUSTINE Project Report, PB2019-02 August 2020 Resilient Heritage in the Nation’s Oldest City St. Augustine, FL Final Report Prepared for City of St. Augustine PB2019-02 by Taylor Engineering, Inc. 10199 Southside Blvd., Ste 310 Jacksonville, FL 32256 The Craig Group 400 E. Kettleman, Ln. Ste. 20 Lodi, CA 95240 Archaeological Consultants, Inc. 8110 Blaikie Court, Suite A Sarasota, Florida 34240 Marquis Latimer + Halback 34 Cordova St. St. Augustine, FL 32084 PlaceEconomics P.O. Box 7529 Washington, DC 20044 August 2020 C2019-054 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The multidisciplinary team made up of Taylor Engineering, The Craig Group, Archaeological Consultants, Inc., Marquis Latimer + Halback, and PlaceEconomics performed this work on behalf of the City of St. Augustine (CoSA). We extend appreciation to the entirety of the CoSA team and the many local and regional stakeholders who provided helpful input. This project’s success is a direct result of the enthusiastic participation of those who contributed their valuable time to share their experiences, knowledge, insight, and areas of expertise. This instrumental group includes representatives of the City of St. Augustine, University of Florida (UF), Historical Architectural Review Board (HARB), National Park Service (NPS), St. Augustine Historical Society, St. Johns County (SJC), St. Augustine Lighthouse Archaeological Maritime Program (LAMP), St. Augustine Archaeological Association, the Florida Public Archaeology Network (FPAN), the Lightner Museum, the Woman’s Exchange of St. Augustine, First Coast/Sotheby’s International Realty; and St. Augustine, Ponte Vedra & The Beaches Visitors & Convention Bureau. This project is sponsored in part by the Department of State, Division of Historical Resources and the State of Florida. -

Liiiibiiiiiiiiiiiiil^

ME: ARCHITECTURE Form 10-300 UNITED IOR (Rev. 6-72) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Virginia COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES KMTI01IAL HISTOj^ENTQRY - NOMINATION FORM Prince George FOR NPS USE ONLY LANDMARKS) ENTRY DATE (Type all entries - complete applicable sections) Brandon, Brandon Plantation "Lower Brandnn" AND/OR HISTORIC: __________Brandon. Brandon Plantation <'Lower RranHnn" STREET AND, NUMBER: Brandon Plantation CITY OR TOWN: CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT: Spring Grove fnear Burrowsvl11 nna._____ COUNTY: Virginia George 1 AQ CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC D District Q Building Public Public Acquisition: [ | Occupied Yes: Q Restricted D Site Q Structure Private Q In Process II Unoccupied Q] Unrestricted D Object Both | | Being Considered I I Preservation work in progress D No PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) I | Agricultural I | Government D Pork I I Transportation I I Comments I | .Commercial I I Industrial I | Private Residence n Other (Specify) I I Educational n Military I | Religious I I Entertainment II Museum I | Scientific OWNER'S NAME: <r! H £ > Congressman Robert W. Daniel . .Tr STREET AND NUMBER: (2 m H« 3 Brandon Plantation H- CITY OR TOWN: ____;,,,.....,„.. - - - •• -. —— Burrowsyi 11 e) ?^Rai 1liiiiBiiiiiiiiiiiiil^ COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: Clerk of the Circuit Court, Prince George County Courthouse STREET AND NUMBER: on courthouse Road off Route 106, 3 miles from the junctionoo" 106 §460, across s;treet from Guerin'c; <;tr»re Mailing addr. p - n Ry Cl TY OR TOWN: -

St. Augustine National Register Historic District (2016)

ST. AUGUSTINE INVENTORY ST. JOHNS COUNTY, FLORIDA Prepared for The City of St. Augustine St. Augustine, Florida and Florida Department of State Division of Historical Resources Tallahassee, Florida Prepared by Patricia Davenport, MHP Environmental Services, Inc. and Paul Weaver Historic Property Associates, Inc. 30 June 2016 Grant No. S1601 ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES, INC. 7220 Financial Way, Suite 100 Jacksonville, Florida 32256 (904) 470-2200 St. Augustine National Register Historic District Survey Report For the City of St. Augustine EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Environmental Services Inc. of Jacksonville, Florida with assistance from Historic Property Associates of St. Augustine, Florida, conducted an inventory of structures within the St. Augustine National Register Historic District, for the City of St. Augustine, St. John’s County, Florida from December 2015 through June 2016. The survey was conducted under contract number RFP #PB2016-01 with the City of St. Augustine to fulfill requirements under a Historic Preservation Small-Matching Grant (CSFA 45.031), grant number S1601. The objectives of the survey was to update the inventory of historic structures within the St. Augustine National Register Historic District, and to record and update Florida Master Site File (FMSF) forms for all structures 45 years old or older, and for any “reconstructions” on original locations utilizing the Historic Structure Form and assess their eligibility for listing in the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP). All work was intended to comply with Section 106 of the National Historic preservation Act (NHPA) of 1966 (as amended) as implemented by 36 CFR 800 (Protection of Historic Properties), Chapter 267 F.S. and the minimum field methods, data analysis, and reporting standards embodied in the Florida Division of Historic Resources’ (FDHR) Historic Compliance Review Program (November 1990, final draft version). -

Draft of the Historic Preservation Plan

CITY OF ST. AUGUSTINE HISTORIC PRESERVATION MASTER PLAN DRAFT 21 AUGUST 2017 Preservation Design Partnership, llc Table of Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION 2.0 HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT (to be provided) 3.0 THE CITY TODAY 4.0 HISTORIC PRESERVATION IN ST. AUGUSTINE 5.0 HISTORIC PRESERVATION STRATEGIES 6.0 IMPLEMENTATION APPENDICES (to be provided) Resources DRAFTS.W.O.T Analysis DRAFT Introduction1 DRAFT Introduction The rich and varied history of St. Augustine has been a key component of its vitality and growth. The development pressures associated with the city’s desirability for residents, businesses and tourists is altering the historic nature and character of St. Augustine at what appears today to be an alarming pace. While development pressure is a man-made threat the city is also facing a natural threat associated with rising sea levels. With the threats affecting St. Augustine’s historic, neighborhood character, there is a rising desire to balance necessary change with preservation in a way that the city’s essential culture and sense of place is protected and maintained. The goal of this Historic Preservation Master Plan (Plan) is to identify goals, strategies and policies to support the continued preservation of the city and its diverse, neighborhood culture for future generations. While the historic character of St. Augustine has been a key element in the city’s economic success, it is also posing or heightening certain challenges: • Tourism: Tourism is the largest economy in St. Augustine, but the demands of tourists are encouraging modifications -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting Template

ORIGINS AND DEVELOPMENT OF SHELL-BASED CONSTRUCTION IN ST. AUGUSTINE By TREY ALEXANDER ASNER A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF HISTORICAL PRESERVATION UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2020 © 2020 Trey Alexander Asner To my friend and mentor Jean Wagner Wilhite Troemel (1921-2018) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My sincere appreciation I would like to extend to the members of my thesis committee for their encouragement, enthusiasm, and guidance: from the Department of Design Construction and Planning, committee chair Prof. Morris Hylton III and co-chair Lect. Judi Shade Monk. I would also like to thank Dr. Linda Stevenson who also helped guide me throughout the completion of my degree. Special thanks are to be given to Charles Tingley, Bob Nawrocki, Chad Germany, and Claire Barnewolt of the St. Augustine research library who helped me acquire the archival information that was instrumental for my research. In addition, I would also like to thank Dr. Thomas Graham and David Nolan whose publications were crucial in my research. Finally, I would like to thank my brothers Jesse and Chase, my friends Roger and Sarah Bansemer, and my canine “Mr. Pim” who supported and motivated me throughout all stages of this research from inception to completion. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...............................................................................................................4 LIST OF FIGURES .........................................................................................................................8