Draft of the Historic Preservation Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form 1

ntt NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections__________________ 1. Name__________________ historic Holy Assumption Orthodox Church_________________ and/or common Church of the Holv Assumption of the Virgin Mary 2. Location street & number Mission & Overland Streets not for publication city, town Kenai vicinity of state Alaska code county code 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public J£ _ occupied agriculture museum building(s) X private unoccupied commercial park _ structure both work in progress educational X private residence X site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment _X _ religious object in process _X _ yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation N.A. no military other: 4. Owner of Property name Alaska Diocese, Orthodox Church in America street & number Box 728 city, town Kodiak vicinity of state Alaska 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. U. S. Bureau of Land Management street & number 701 C Street city, town Anchorage state Alaska 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Alaska Heritage Resources title $urvev has this property been determined eligible? y yes __ no date June 16, 1972 federal _%_ state county local Office of History & Archeology, Alaska State Division of Parks depository for survey records pniirh 7nm (^ PnrHnya) Olympic Bldg.___________________ city, town Anchorage state Alaska 7. Description Condition Check one Check one __ excellent __ deteriorated __ unaltered _X_ original site _X_ good __ ruins _X_ altered __ moved date __ fair __ unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance See Continuation Sheet, NO. -

Historic Preservation in St.4Augustine

Historic Preservation in St.4Augustine Historic Preservation in St. Augustine The Ancient City By William R. Adams In the aftermath of St. Augustine’s fiery destruction at the hands of Governor The following essay was written by Dr. George Moore in 1702, the residents set about rebuilding the town. Little William Adams and published in the St. remained but the stone fortress that had sheltered them from the British and Augustine Historical Society’s publication the century-old plan for the colonial presidio, marked by the central plaza El Escribano. Permission to use within this and a rough pattern of crude streets that defined a narrow, rectangular grid document was granted by the author and the St. Augustine Historical Society. It was along the west bank of the Matanzas River, or what is now the Intracoastal composed in 2002 as a reflection of St. Waterway. In building anew, the Spanish residents employed materials more Augustine’s growth in the context of the durable than the wood and thatch which had defined the town the British preservation movement looking forward torched. to the 21st century. William R. (Bill) Adams St. Augustine is not just another city with a history. All cities boast a past. Nor received a Ph.D. in history at Florida State University and served as director of the is St. Augustine merely the nation’s oldest city. What it claims in the pages of Department of Heritage Tourism for the U. S. history is the distinction as the capital of Spain’s colonial empire in North City of St. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB NO. 1024-0018 Expires 10-31-87 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS us« only ._ MAY 27 1986 National Register off Historic Places received ll0 Inventory Nomination Form date entered &> A// J^ See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name historic St. Augustine Historic District and or common 2. Location N/A street & number __ not for publication St. Augustine city, town vicinity of Florida state code 12 county St. Johns code 109 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use x district public occupied agriculture X museum building(s) private X unoccupied ^ commercial X .park structure X both work in progress X educational X . private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible X entertainment X religious object in process yes: restricted X government scientific being considered X yes: unrestricted industrial transportation x military . other: 4. Owner off Property name Multiple street & number N/A St. Augustine N/A city, town vicinity of state Florida 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. St. Johns County Courthouse street & number 95 Cordova Street city, town St. Augustine state Florida 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title St. Augustine Survey has this property been determined eligible? X yes __ no date 1978-1986 federal X state county local depository for survey records Florida Department of State; Hist. St. Augustine Preservation Bd, city, town Tallahassee and St. Augustine state Florida 7. Description Condition Check one Check one ___4;ejteeHent . deteriorated unaltered original site OOOu ruins altered moved date __ fair unexposed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance SUMMARY OF PRESENT AND ORIGINAL PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The revised St. -

The Gilded Age: the Lighter Museum & More

Discover the Gilded Age: The Lightner Museum & More DAY 1 St. Augustine is rich in history, and in the late 1800s, “rich” was the operative word. This little town became the premier resort destination for the well-to-do – and it all began in 1883 with an auspicious visit by Henry Morrison Flagler, John D. Rockefeller’s partner in founding Standard Oil. Stroll back in time as you explore the historic Lightner Museum, former Ponce de Leon Hotel and more with this guide to the Gilded Age in St. Augustine. We’ve included suggestions for drinking, dining, and discovering your way through an opulent era of lavish architecture and conspicuous luxury. MORNING Breakfast and Flagler Legacy Tour The Blue Hen Café Quaint and quirky comfort food with options like blue crab quiche, corned beef hash and eggs, chicken biscuits, and more. 117 M L King Ave, St. Augustine, FL (904) 217-3777 | https://www.visitstaugustine.com/restaurant/blue-hen Flagler Legacy Tour Built by Henry M. Flagler at the height of the Gilded Age, and one of the most exclusive resorts of its day, Historic Tours of the former Hotel Ponce de Leon highlight the Spanish Renaissance architectural heritage of what is now Flagler College. 59 St. George Street, St. Augustine, FL (904) 823-3378 | https://legacy.flagler.edu/pages/tours AFTERNOON Lunch and Explore Downtown and Flagler’s Churches The Floridian Local, seasonal and sustainable ingredients in a comfortable and casual atmosphere. Taste southern comfort food and vibrant, creative dishes with many vegetarian options. 72 Spanish Street, St. Augustine, FL (904) 829-0655 | http://www.thefloridianstaug.com/ Experience the Gilded Age in St. -

Coastal Realty Presents St Augustine Visitor Guide©

Coastal Realty Presents St Augustine Visitor Guide© Events & Festivals Historical Reenactments Free Things to Do Adventures Just for Kids Rainy Day Activities Concerts & Theater Shows Locals’ Favorite Watering Holes Restaurant & Attraction Recommendations Beach, Bike, & Boat Rentals Houses of Worship 3942 A1A South St Augustine, Florida 32080 904-471-6606 www.coastalrealtyvacationrentals.com EVENTS & FESTIVALS IN ST AUGUSTINE ONGOING First Friday Art Walk Self-guided walk of local art galleries along King and Aviles streets on the first Friday of every month, 5 pm to 9 pm. Features special exhibits and refreshments. Uptown Saturday Night On the last Saturday of every month, take a self-guided walk of local shops and galleries along San Marco Avenue, north of the parking garage. Music and refreshments. Old City Farmer’s Market Saturdays 830 am – 1230 pm St Augustine Amphitheatre Produce, baked goods, plants, local crafts, food trucks. The Night Market is the 2nd and 4th Tuesday from 6-9 pm, March through October. Farmer’s Arts & Crafts Market Wednesdays 8 am – 12 pm St Johns County Pier Park Produce, baked goods, plants, local crafts, food trucks. ONGOING NATURE & HISTORICAL EVENTS Guana Tolomato Matanzas Guided Beach Exploration Third Saturday of every month 2200 Ponte Vedra Blvd in Ponte Vedra Beach (Coastal Highway) Take a 2-hour guided hike along the beach and learn about the various plants and animals that call the beach home. Parking is $3. Visit the website to reserve your spot. Click on “visit” and “events.” https://gtmnerr.org First Saturday Nature Hike at Guana River State Park 9am-11am Ponte Vedra Beach Guided walking tour meets at pavilion just west of Guana dam. -

Examples of St.Augustine's Varied Architecture Include the Spanish-Style Cathedral-Basilica of St.Augustine

StAugustine_SO2007 7/26/07 10:45 AM Page 4848 Examples of St.Augustine’s varied architecture include the Spanish-style Cathedral-Basilica of St.Augustine (top); the dramatic Flagler Memorial Presbyterian Church (center left and bottom right); the late seventeenth- century Castillo de San Marco (center, second from right); and the ornate former Ponce de León Hotel, which now houses Flagler College (bottom left). TOP PHOTO BY NATALIA BRATSLAVSKY; OTHER PHOTOS BY CHELLE KOSTER WALTON BY CHELLE KOSTER PHOTOS OTHER BRATSLAVSKY; BY NATALIA PHOTO TOP 52 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2007 StAugustine_SO2007 7/26/07 10:45 AM Page 4849 Spires, Steeples, & Stucco On the trail of St. Augustine’s architectural jewels by Chelle Koster Walton browsed splendid art-glass creations in a Spanish some of these characters out of the corner of your eye.Yes, St. Colonial–style home on St. George Street. Across the Augustine bears a reputation for ghosts, but these apparitions way, I toured a shrine devoted to the history and her- are flesh and blood, reenactors who walk the streets and itage of St. Augustine’s Greeks in North America’s ear- demonstrate at the Colonial Spanish Quarter Museum and liest surviving house of worship, built circa 1735. I later Castillo de San Marco. Ishopped for antiques and had lunch in the deep end of what Life and architecture in St. Augustine began well before the was once the largest indoor pool in America. I then toured a building of Castillo de San Marco, the coquina (or coral lime- college that occupies a former Spanish Renaissance–style stone) fort that has withstood the onslaughts of man and grand hotel. -

Alcazar Hotel (Lightner Municipal Exposition) AND/OR HISTORIC: Historic Lightner Museum Ill STREET and NUMBER: 79 King Street CITY OR TOWN: St

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERV ICE Florida COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HIS'FORIC PLACES St. Johns INVENTORY - NOMINAT ION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER DATE (lype all entries — complete app 'icable sections) *? li 3>/£- OOO \ 'ZL/Zy/VJ "^^^^^f^^^^^iiiiiii^^mf- COMMON: Alcazar Hotel (Lightner Municipal Exposition) AND/OR HISTORIC: Historic Lightner Museum ill STREET AND NUMBER: 79 King Street CITY OR TOWN: St. Augustine STATE CODE COUNTrY: CODE Florida 12 £>t. Johns 109 CATEGORY OWNERSHIP I STATUS ACCESSIBLE (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC n District [3f Building D Public Public Acquisition: • £j Occupied Yes: nn . , [2£ Restricted n Site Q Structure D Private | | In Process [_] Unoccupied L— ^ red i — 10 . CD Unrestricted D Object LX Both | | Being Conside rea r— ] Preservation work in progress 1 —' *^° PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) 1 1 Agricultural Q Government | | Park I | J^ftSipirlafhoR'N^ 1 1 Comments ffi Commercial 1 1 Industrial | | Private Residence X] Educational [~1 Mi itary | | Religious jfiQr' ^ rt X--?"x \ jF| Entertainment S3 Museum "g~] Scientific /! '• RtctivED c\ Illliilliiilllilllilllllllllllll OWNER'S NAME: U) City of St. Augustine \pv NATIONAL /5/ ^ IT STREET AND NUMBER: \X:V REblb i L,.» ^y 0 City Hall H- CITY OR TOWN: STPATE: ^"^C/Ci ' ! \^>^' CODE OJ St. Augustine Florida 12 :::-::::::::::::::::::::::::::::¥:::¥^ :>•:•:•:•:•:•:•:•:•:•¥•:•:•:•:•:•: i^SJIoKSSiSSSSSSSiS:^^ COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: cn COUNTY: St. Johns County Courthouse rt STREET AND NUMBER: King and Cordova Streets O Cl TY OR TOWN: SI•ATE CODE CO St. Augustine Florida 12 :: : : : :::: : :::::::::: :;^ ::::::::::^:::::: ::: ::::::::::::::;:::;:::::;:::::::::::::--:::-:^:0:^:::0::^ b$ ; ::: : :::;: :;::: :::: : : :::;: :::::::::::::::.::;::.:.;.:.:.:<.:<-:.:-:.:-:::-:-: : :-::; :::: ::::: ;;:::::::::;:;::::::::::::x^ TITLE OF SURVEY: X> ENTR ^-^ Part of St. -

1 Preserving the Legacy the Hotel

PRESERVING THE LEGACY THE HOTEL PONCE DE LEON AND FLAGLER COLLEGE By LESLEE F. KEYS A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2013 1 © 2013 Leslee F. Keys 2 To my maternal grandmother Lola Smith Oldham, independent, forthright and strong, who gave love, guidance and support to her eight grandchildren helping them to pursue their dreams. 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My sincere appreciation is extended to my supervisory committee for their energy, encouragement, and enthusiasm: from the College of Design, Construction and Planning, committee chair Christopher Silver, Ph.D., FAICP, Dean; committee co-chair Roy Eugene Graham, FAIA, Beinecke-Reeves Distinguished Professor; and Herschel Shepard, FAIA, Professor Emeritus, Department of Architecture. Also, thanks are extended to external committee members Kathleen Deagan, Ph.D., Distinguished Research Professor Emeritus of Anthropology, Florida Museum of Natural History and John Nemmers, Archivist, Smathers Libraries. Your support and encouragement inspired this effort. I am grateful to Flagler College and especially to William T. Abare, Jr., Ed.D., President, who championed my endeavor and aided me in this pursuit; to Michael Gallen, Library Director, who indulged my unusual schedule and persistent requests; and to Peggy Dyess, his Administrative Assistant, who graciously secured hundreds of resources for me and remained enthusiastic over my progress. Thank you to my family, who increased in number over the years of this project, were surprised, supportive, and sources of much-needed interruptions: Evan and Tiffany Machnic and precocious grandsons Payton and Camden; Ethan Machnic and Erica Seery; Lyndon Keys, Debbie Schmidt, and Ashley Keys. -

National Historic Landmark

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK. Theme: Architecture Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (Rev. 6-72) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Maryland COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Anne Arundel T "~ 0lt4VENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY "— ; ENTRY DATE (Type all entries complete applicable sections) London Town Publik House AND/OR HISTORIC: London Town Publik House STREET ANO NUMBER: End of London Town Road on South Bank of South River CITY OR TOWN: CONGRESSIONAL. DISTRICT: Vicinity of Annapolis 4th COUNT Y. Anne Mb CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) O District gg Building Public Public Acquisition: D Occupied Yes: i —i M . , I I Restricted Q Site Q Structure CD Private §2 In Process [_J Unoccupied ' — ' _, _ , Kl Unrestricted D Object { | Both [ | Being Considered | _| Preservation work in progress ' — ' PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) Agricultural 1 | Government [ | Park I I Transportation 1 1 Comments .Commercial 1~1 Industrial |~] Private Residence [D Other (Specify) Educational CD 'Military Q Religious Entertainment 83 Museum Q Scientific OWNER'S NAME: .-, - Lounty of Anne Arundel; administered by London Town Publik House Commission, Mr. Y. Kirlcpatrick Howat Chairman STREET AND NUMBER: -1 * w I*1 X Contee Farms CITY OR TOWN: STATE: CODF Edgewater Maryland 9/1 COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: Anne Arundel County Court House— Clerk of Circuit Court ArundelAnne COUNTY: STREET AND NUMBER: P.O. Box 71 C1 TY OR TOWN: STATE . CODE Annapolis Maryland 21404 24 T1TUE OF SURVEY: . • . Historic American Buildings Survey (8 photos) NUMBERENTRY 0 DATE OF SURVEY: 1936, 1937 XX Federal n Statc D County Q Loca 70 DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: -DZ cn Library of Congress/ Annex C STREET AND NUMBER: '•.... -

Front Cover: the Llambias House of St Augustine, Florida

The following article on the Llambias House National Historic Landmark was originally published in the Front Cover: The Llambias House of St Augustine, Southwestern Mission Research Center's (SMRC) Revista newsletter Volume 43, no. 160-161, 2009. Permission was granted by the President of SMRC by email on July 14, 2015 for a PDF copy to be made Florida. (Photo courtesy of Mark R. Barries.) of this article and posted on the National Park Service Electronic Library website, http://npshistory.com/. All rights reserved. 14 • News & Events SMRC REVISTA Figure 1. View of the front (north) and east elevations of the Llanibias House, looking southwest. (Photo courtesy of the St. Augustine Historical Society.) THE LLAMBIAS HOUSE: AN EXAMPLE OF SPANISH COLONIAL CARIBBEAN HOUSING IN THE SOUTHEASTERN UNITED STATES by MARK R. BARNES, PH.D. The Llambias House, located at 31 St. Francis Street in the south the edges of the house lot to enclose an interior courtyard. A ernmost section of the old Spanish colonial town of St. Augus notable feature of the St. Augustine Plan was a lack of direct tine, Florida, is a nationally significant example of the Spanish access to the interior of the residence from the street. Instead, colonial "St. Augustine Plan" of residential architecture that access was provided through a gate in the garden wall which led may be found throughout the Spanish Antilles (Figure 1). The to the courtyard, with two variations based on the manner of definitive work on this architectural style was produced in the access from the courtyard to the dwelling's interior: through a early 1960s by Albert Manucy and then expanded upon by other covered porch on the building's rear or through a covered loggia researchers. -

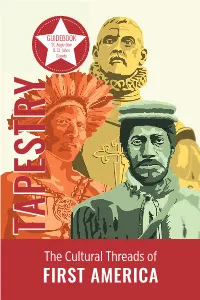

Tapestry Passport Program Created by the City of St

GUIDEBOOK St. Augustine & St. Johns County TAPESTRY TAPESTRY The Cultural Threads of FIRST AMERICA WELCOME TO GUIDEBOOK ST. AUGUSTINE! PROGRAM This program is designed to St. Augustine is America’s first connect you with important city, established in 1565. It is a city historic sites and programs in built on discovery, courage and St. Augustine and St. Johns enduring spirit; it is a city built by County. Use the map and pioneers, soldiers, artisans and destination descriptions to entrepreneurs. More than four navigate your way to the locations and a half centuries later, the (most are in walking distance). town and its people continue to symbolize the rich history and cultural diversity that makes St. Augustine unique. We welcome you to the Nation’s Oldest City and invite you to explore our rich history. Photo by Daniel J. Bagan The guidebook is divided into three historic periods designated by color. STARTING LOCATION 1 - Visitor Information Center DO FIRST AMERICA W 2 - Mission Nombre de Dios 3 - Fountain of Youth Archaeological Park NTO COLONIAL ST. AUGUSTINE 4 - City Gate and Cubo Defense Line W 5 - Castillo de San Marcos National Monument 6 - Tolomato Cemetery N 7 - Colonial Quarter DE 8 - St. Augustine Pirate & Treasure Museum 9 - St. Photios Greek Orthodox National Shrine S 10 - Peña-Peck House TIN 11 - Cathedral Basilica of St. Augustine 12 - Father Pedro Camps Monument 13 - Governor’s House Cultural Center & Museum A 14 - Plaza de la Constitución TION 15 - Spanish Constitution Monument 16 - Aviles Street 17 - Spanish Military Hospital Museum 18 - Ximenez-Fatio House Museum S 19 - Father Miguel O’Reilly House Museum 20 - St. -

Oral History Index

Oral History Index Transcription Digital Collections Available Interviewee(s)/Speaker(s) OH# N/A Yes (OH1) Adelaide Marguerite Capo OH1-OH12 N/A Yes (OH14) Mary Capo Manucy OH13-OH14 N/A No William H. Manucy, Jr. OH15-OH16 N/A No Joseph Herman Manucy Jr., pianist; Dave Middleton, SaxophonistOH17 N/A Yes (OH18-OH19) Albert Manucy OH18-OH20 1 Revised Nov 2020 NMD Oral History Index Transcription Digital Collections Available Interviewee(s)/Speaker(s) OH# Family memories: Albert Manucy, Mark Manucy, Ann Day N/A No Manucy, and Gonzalez (the cat) OH21 N/A No James Manucy OH22 N/A No Elizabeth Archer Manucy OH23-OH27 N/A No The Archer Family/Charleston Manucys OH28 N/A No The Charles. D. Segui Family OH29 N/A No Charles I. Ortegas OH30 N/A No Alton Jerome "John" Westbrook OH31 High School Class of 1923: Arthur A. Manucy, Worth N/A No Gaines, and Marjorie Lindscott Gaines OH32 N/A No Arthur Manucy OH33-OH35 N/A No X. L. Pellicer OH36 Sundry St. Augustinians Yes J. (John) Carver Harris OH37 Sundry St. Augustinians Yes Joseph P. McAloon OH38 Sundry St. Augustinians Yes Haynes Grant, Sr. OH39 2 Revised Nov 2020 NMD Oral History Index Transcription Digital Collections Available Interviewee(s)/Speaker(s) OH# Oral History Programs Yes Talk of the Town - Margaret Manford OH40 Sundry St. Augustinians Yes Major Argrett OH41 N/A No David Benjamin "D. B." Green OH42-OH43 Sundry St. Augustinians Yes Florence Clements Samuels OH44 Sundry St. Augustinians Yes Charles Colee OH45-OH46 N/A No Earl Masters OH47 3 Revised Nov 2020 NMD Oral History Index Transcription Digital Collections Available Interviewee(s)/Speaker(s) OH# Sundry St.