10 Reasons to Covet Our Coast on the Beach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PART 1 BDV25 TWO977-25 Task 2B Delive

EVALUATION OF SELF CONSOLIDATING CONCRETE AND CLASS IV CONCRETE FLOW IN DRILLED SHAFTS – PART 1 BDV25 TWO977-25 Task 2b Deliverable – Field Exploratory Evaluation of Existing Bridges with Drilled Shaft Foundations Submitted to The Florida Department of Transportation Research Center 605 Suwannee Street, MS30 Tallahassee, FL 32399 [email protected] Submitted by Sarah J. Mobley, P.E., Doctoral Student Kelly Costello, E.I., Doctoral Candidate and Principal Investigators Gray Mullins, Ph.D., P.E., Professor, PI Abla Zayed, Ph.D., Professor, Co-PI Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering University of South Florida 4202 E. Fowler Avenue, ENB 118 Tampa, FL 33620 (813) 974-5845 [email protected] January, 2017 to July, 2017 Preface This deliverable is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements set forth and agreed upon at the onset of the project and indicates a degree of completion. It also serves as an interim report of the research progress and findings as they pertain to the individual task-based goals that comprise the overall project scope. Herein, the FDOT project manager’s approval and guidance are sought regarding the applicability of the intermediate research findings and the subsequent research direction. The project tasks, as outlined in the scope of services, are presented below. The subject of the present report is highlighted in bold. Task 1. Literature Review (pages 3-90) Task 2a. Exploratory Evaluation of Previously Cast Lab Shaft Specimens (page 91-287) Task 2b. Field Exploratory Evaluation of Existing Bridges with Drilled Shaft Foundations Task 3. Corrosion Potential Evaluations Task 4. Porosity and Hydration Products Determinations Task 5. -

Unearthing St. Augustine's Colonial Heritage

Unearthing St. Augustine’s Colonial Heritage: An Interactive Digital Collection for the Nation’s Oldest City Abstract In preparation for St. Augustine’s 450th anniversary of its founding in 2015, the University of Florida (UF) Libraries requests $341,025 from the National Endowment for the Humanities to build an online collection of key resources related to colonial St. Augustine, Florida. Along with the UF Libraries, the Unearthing St. Augustine project partners are the St. Augustine Department of Heritage Tourism and historic Government House, the St. Augustine Historical Society, and the City of St. Augustine Archaeology Program. This two-year project will have two major outcomes: 1) UF and its partners will create and disseminate an interactive digital collection consisting of 11,000 maps, drawings, photographs and documents and associated metadata that will be available freely online, and 2) project staff will create original programming for a user-friendly, map-based interface, and release it as open-source technology. In addition to providing digital access to numerous rare and desirable resources, the primary goal is to create a flexible, interactive environment in which users will be comfortable using and manipulating objects according to different research needs. Along with searching and browsing functions—including full text searching—the project will develop a map-based interface built upon geographic metadata. Users will be able to search for textual information, structural elements and geographic locations on maps and images. This model will encourage users to contribute geospatial metadata and participate in the georectification of maps. For the first time, this project brings the study of St. -

First Coast TIM Team Meeting Tuesday, March 16Th, 2021 Meeting Minutes

First Coast TIM Team Meeting Tuesday, March 16th, 2021 Meeting Minutes The list of attendees, agenda, and meeting handouts are attached to these meeting minutes. *For the health and safety of everyone, this meeting was held virtually to adhere to COVID-19 safety guidelines. Introductions and TIM Updates • Dee Dee Crews opened the meeting and welcomed everyone. • Dee Dee read the TIM Team Mission statement as follows: The Florida Department of Transportation District 2 Traffic Incident Management Teams through partnering efforts strive to continuously reduce incident scene clearance times to deter congestion and improve safety. The Teams’ objective is to exceed the Open Roads Policy thus ensuring mobility, economic prosperity, and quality of life. The Vision statement is as follows: Through cooperation, communication and training the Teams intend to reduce incident scene clearance times by 10% each year. • The January 2021 First Coast TIM Team Meeting Minutes were sent to the Team previously, and receiving no comments, they stand as approved. Overland Bridge and Your 10 & 95 Project Updates by Tim Heath • The Fuller Warren Bridge improvements are ongoing. The decking operations have started on the 4 center spans. • The Ramp T Stockton St. exit is scheduled to open on April 30th. This ramp goes from I-95 Northbound to I-10 Westbound. • There will be no other major changes to the current traffic patterns at this time. The traffic pattern will remain the same during the day and there will be nighttime lane closures and detours for construction. Construction Project Update by Hampton Ray • The I-10 Widening project from I-295 to where the I-10 and I-95 Operational Improvements project stops will be ongoing for the next several years. -

NORTH FLORIDA TPO Transportation Improvement Program FY 2021/22 - 2025/26

NORTH FLORIDA TPO Transportation Improvement Program FY 2021/22 - 2025/26 Draft April 2021 North Florida TPO Transportation Improvement Program - FY 2021/22 - 2025/26 Table of Contents Section I - Executive Summary . I-1 Section II - 5 Year Summary by Fund Code . II-1 Section III - Funding Source Summary . III-1 Section A - Duval County State Highway Projects (FDOT) . A-1 Section B - Duval County State Highway / Transit Projects (JTA) . B-1 Section C - Duval County Aviation Projects . C-1 Section D - Duval County Port Projects . D-1 Section E - St. Johns County State Highway / Transit Projects (FDOT) . E-1 Section F - St. Johns County Aviation Projects . F-1 Section G - Clay County State Highway / Transit / Aviation Projects (FDOT) . G-1 Section H - Nassau County State Highway / Aviation / Port Projects (FDOT) . H-1 Section I - Area-Wide Projects . I-1 Section J - Amendments . J-1 Section A1 - Abbreviations and Acronyms (Appendix I) . A1-1 Section A2 - Path Forward 2045 LRTP Master Project List (Appendix II) . A2-1 Section A3 - Path Forward 2045 LRTP Goals and Objectives (Appendix III) . A3-1 Section A4 - 2020 List of Priority Projects (Appendix IV) . A4-1 Section A5 - Federal Obligation Reports (Appendix V) . A5-1 Section A6 - Public Comments (Appendix VI) . A6-1 Section A7 - 2045 Cost Feasible Plan YOE Total Project Cost (Appendix VII) . A7-1 Section A8 - Transportation Disadvanagted (Appendix VIII) . A8-1 Section A9 - FHWA Eastern Federal Lands Highway Division (Appendix IX) . A9-1 Section A10 – Transportation Performance Measures (Appendix X). A10-1 Section PI - Project Index . PI-1 Draft April 2021 SECTION I Executive Summary EXECUTIVE SUMMARY PURPOSE The Transportation Improvement Program (TIP) is a staged multi-year program of transportation project improvements to be implemented during the next five-year period in the North Florida TPO area which will be funded by Title 23 U.S.C. -

The Jacksonville Downtown Data Book

j"/:1~/0. ~3 : J) , ., q f>C/ An informational resource on Downtown Jacksonville, Florida. First Edjtion January, 1989 The Jacksonville Downtown Development Authority 128 East Forsyth Street Suite 600 Jacksonville, Florida 32202 (904) 630-1913 An informational resource on Downtown Jacksonville, Florida. First Edition January, 1989 The Jackso.nville Dpwntown Development ·.. Authority ,:· 1"28 East Forsyth Street Suite 600 Jacksonville, Florida 32202 (904) 630-1913 Thomas L. Hazouri, Mayor CITY COUNCIL Terry Wood, President Dick Kravitz Matt Carlucci E. Denise Lee Aubrey M. Daniel Deitra Micks Sandra Darling Ginny Myrick Don Davis Sylvia Thibault Joe Forshee Jim Tullis Tillie K. Fowler Eric Smith Jim Jarboe Clarence J. Suggs Ron Jenkins Jim Wells Warren Jones ODA U.S. GOVERNMENT DOCUMENTS C. Ronald Belton, Chairman Thomas G. Car penter Library Thomas L. Klechak, Vice Chairman J. F. Bryan IV, Secretary R. Bruce Commander Susan E. Fisher SEP 1 1 2003 J. H. McCormack Jr. Douglas J. Milne UNIVERSITf OF NUt?fH FLORIDA JACKSONVILLE, Flur@A 32224 7 I- • l I I l I TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Tables iii List of Figures ..........•.........•.... v Introduction .................... : ..•.... vii Executive SUllllllary . ix I. City of Jacksonville.................... 1 II. Downtown Jacksonville................... 9 III. Employment . • . • . 15 IV. Office Space . • • . • . • . 21 v. Transportation and Parking ...•.......... 31 VI. Retail . • . • . • . 43 VII. Conventions and Tourism . 55 VIII. Housing . 73 IX. Planning . • . 85 x. Development . • . 99 List of Sources .........•............... 107 i ii LIST OF TABLES Table Page I-1 Jacksonville/Duval County Overview 6 I-2 Summary Table: Population Estimates for Duval County and City of Jacksonville . 7 I-3 Projected Population for Duval County and City of Jacksonville 1985-2010 ........... -

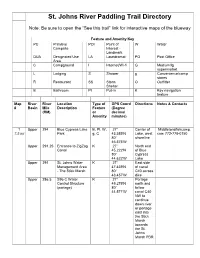

St. Johns River Blueway by Dean Campbell River Overview

St. Johns River Paddling Trail Directory Note: Be sure to open the “See this trail” link for interactive maps of the blueway Feature and Amenity Key PC Primitive POI Point of W Water Campsite Interest - Landmark DUA Designated Use LA Laundromat PO Post Office Area C Campground I Internet/Wi-fi G Medium/lg supermarket L Lodging S Shower g Convenience/camp stores R Restaurant SS Storm O Outfitter Shelter B Bathroom PI Put-in K Key navigation feature Map River River Location Type of GPS Coord Directions Notes & Contacts # Basin Mile Description Feature (Degree (RM) or decimal Amenity minutes) 1 Upper 294 Blue Cypress Lake B, PI, W, 27° Center of Middletonsfishcamp. 7.5 mi Park g, C 43.589'N Lake, west com 772-778-0150 80° shoreline 46.575'W Upper 291.25 Entrance to ZigZag K 27° North end Canal 45.222'N of Blue 80° Cypress 44.622'W Lake Upper 291 St. Johns Water K 27° East side Management Area 47.439'N of canal - The Stick Marsh 80° C40 across 43.457'W dike Upper 286.5 S96 C Water K 27° Portage Control Structure 49.279'N north and (portage) 80° follow 44.571'W canal C40 NW to continue down river or portage east into the Stick Marsh towards the St. Johns Marsh PBR Upper 286.5 St. Johns Marsh – B, PI, W 27° East side Barney Green 49.393'N of canal PBR* 80° C40 across 42.537'W dike 2 Upper 286.5 St. Johns Marsh – B, PI, W 27° East side 22 mi Barney Green 49.393'N of canal *2 PBR* 80° C40 across day 42.537'W dike trip Upper 279.5 Great Egret PC 27° East shore Campsite 54.627'N of canal 80° C40 46.177'W Upper 277 Canal Plug in C40 K 27° In canal -

1 Preserving the Legacy the Hotel

PRESERVING THE LEGACY THE HOTEL PONCE DE LEON AND FLAGLER COLLEGE By LESLEE F. KEYS A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2013 1 © 2013 Leslee F. Keys 2 To my maternal grandmother Lola Smith Oldham, independent, forthright and strong, who gave love, guidance and support to her eight grandchildren helping them to pursue their dreams. 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My sincere appreciation is extended to my supervisory committee for their energy, encouragement, and enthusiasm: from the College of Design, Construction and Planning, committee chair Christopher Silver, Ph.D., FAICP, Dean; committee co-chair Roy Eugene Graham, FAIA, Beinecke-Reeves Distinguished Professor; and Herschel Shepard, FAIA, Professor Emeritus, Department of Architecture. Also, thanks are extended to external committee members Kathleen Deagan, Ph.D., Distinguished Research Professor Emeritus of Anthropology, Florida Museum of Natural History and John Nemmers, Archivist, Smathers Libraries. Your support and encouragement inspired this effort. I am grateful to Flagler College and especially to William T. Abare, Jr., Ed.D., President, who championed my endeavor and aided me in this pursuit; to Michael Gallen, Library Director, who indulged my unusual schedule and persistent requests; and to Peggy Dyess, his Administrative Assistant, who graciously secured hundreds of resources for me and remained enthusiastic over my progress. Thank you to my family, who increased in number over the years of this project, were surprised, supportive, and sources of much-needed interruptions: Evan and Tiffany Machnic and precocious grandsons Payton and Camden; Ethan Machnic and Erica Seery; Lyndon Keys, Debbie Schmidt, and Ashley Keys. -

Outstanding Bridges of Florida*

2013 OOUUTTSSTTAANNDDIINNGG BBRRIIDDGGEESS OOFF FFLLOORRIIDDAA** This photograph collection was compiled by Steven Plotkin, P.E. RReeccoorrdd HHoollddeerrss UUnniiqquuee EExxaammpplleess SSuuppeerriioorr AAeesstthheettiiccss * All bridges in this collection are on the State Highway System or on public roads Record Holders Longest Total Length: Seven Mile Bridge, Florida Keys Second Longest Total Length: Sunshine Skyway Bridge, Lower Tampa Bay Third Longest Total Length: Bryant Patton Bridge, Saint George Island Most Single Bridge Lane Miles: Sunshine Skyway Bridge, Lower Tampa Bay Most Dual Bridge Lane Miles: Henry H. Buckman Bridge, South Jacksonville Longest Viaduct (Bridge over Land): Lee Roy Selmon Crosstown Expressway, Tampa Longest Span: Napoleon Bonaparte Broward Bridge at Dames Point, North Jacksonville Second Longest Span: Sunshine Skyway Bridge, Lower Tampa Bay Longest Girder/Beam Span: St. Elmo W. Acosta Bridge, Jacksonville Longest Cast-In-Place Concrete Segmental Box Girder Span: St. Elmo W. Acosta Bridge, Jacksonville Longest Precast Concrete Segmental Box Girder Span and Largest Precast Concrete Segment: Hathaway Bridge, Panama City Longest Concrete I Girder Span: US-27 at the Caloosahatchee River, Moore Haven Longest Steel Box Girder Span: Regency Bypass Flyover on Arlington Expressway, Jacksonville Longest Steel I Girder Span: New River Bridge, Ft. Lauderdale Longest Moveable Vertical Lift Span: John T. Alsop, Jr. Bridge (Main Street), Jacksonville Longest Movable Bascule Span: 2nd Avenue, Miami SEVEN MILE BRIDGE (new bridge on left and original remaining bridge on right) RECORD: Longest Total Bridge Length (6.79 miles) LOCATION: US-1 from Knights Key to Little Duck Key, Florida Keys SUNSHINE SKYWAY BRIDGE RECORDS: Second Longest Span (1,200 feet), Second Longest Total Bridge Length (4.14 miles), Most Single Bridge Lane Miles (20.7 miles) LOCATION: I–275 over Lower Tampa Bay from St. -

A Context for Common Historic Bridge Types

A Context For Common Historic Bridge Types NCHRP Project 25-25, Task 15 Prepared for The National Cooperative Highway Research Program Transportation Research Council National Research Council Prepared By Parsons Brinckerhoff and Engineering and Industrial Heritage October 2005 NCHRP Project 25-25, Task 15 A Context For Common Historic Bridge Types TRANSPORATION RESEARCH BOARD NAS-NRC PRIVILEGED DOCUMENT This report, not released for publication, is furnished for review to members or participants in the work of the National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP). It is to be regarded as fully privileged, and dissemination of the information included herein must be approved by the NCHRP. Prepared for The National Cooperative Highway Research Program Transportation Research Council National Research Council Prepared By Parsons Brinckerhoff and Engineering and Industrial Heritage October 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF SPONSORSHIP This work was sponsored by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials in cooperation with the Federal Highway Administration, and was conducted in the National Cooperative Highway Research Program, which is administered by the Transportation Research Board of the National Research Council. DISCLAIMER The opinions and conclusions expressed or implied in the report are those of the research team. They are not necessarily those of the Transportation Research Board, the National Research Council, the Federal Highway Administration, the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials, or the individual states participating in the National Cooperative Highway Research Program. i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The research reported herein was performed under NCHRP Project 25-25, Task 15, by Parsons Brinckerhoff and Engineering and Industrial Heritage. Margaret Slater, AICP, of Parsons Brinckerhoff (PB) was principal investigator for this project and led the preparation of the report. -

Agenda Item St. Johns County Board of County

AGENDA ITEM ST. JOHNS COUNTY BOARD OF COUNTY COMMISSIONERS 4 Deadline for Submission - Wednesday 9 a.m. – Thirteen Days Prior to BCC Meeting 5/2/2017 BCC MEETING DATE TO: Michael D. Wanchick, County Administrator DATE: April 5, 2017 FROM: Phong Nguyen, Transportation Development Manager PHONE: 209-0613 SUBJECT OR TITLE: 2017 Roadway and Transportation Alternatives List of Priority Projects (LOPP) AGENDA TYPE: Business Item BACKGROUND INFORMATION: The Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) and the North Florida Transportation Planning Organization (TPO) request from local governments their project priorities for potential funding of new transportation projects to be considered for inclusion in the new fiscal year (FY 2022/23) of FDOT’s Work Program. This is an annual recurring request to local governments. The St. Johns County Board of County Commissioners is charged with prioritizing all projects within the County, including those within municipal boundaries. The Transportation Advisory Group (TAG), consisting of County staff, representatives of the City of St. Augustine, St. Augustine Beach, Town of Hastings, St. Johns County School Board, St. Johns County Sheriff’s Office, and the St. Augustine-St. Johns County Airport Authority met on March 24, 2017 to review last year’s priorities and to recommend this year’s priorities. The attached LOPP includes recommendations of the TAG for both highway and alternatives projects. 1. IS FUNDING REQUIRED? No 2. IF YES, INDICATE IF BUDGETED. No IF FUNDING IS REQUIRED, MANDATORY OMB REVIEW IS REQUIRED: INDICATE FUNDING SOURCE: SUGGESTED MOTION/RECOMMENDATION/ACTION: Motion to approve the 2017 St. Johns County Roadway and Transportation Alternatives List of Priority Projects (LOPP) for transmittal to the Florida Department of Transportation and the North Florida TPO. -

Oral History Index

Oral History Index Transcription Digital Collections Available Interviewee(s)/Speaker(s) OH# N/A Yes (OH1) Adelaide Marguerite Capo OH1-OH12 N/A Yes (OH14) Mary Capo Manucy OH13-OH14 N/A No William H. Manucy, Jr. OH15-OH16 N/A No Joseph Herman Manucy Jr., pianist; Dave Middleton, SaxophonistOH17 N/A Yes (OH18-OH19) Albert Manucy OH18-OH20 1 Revised Nov 2020 NMD Oral History Index Transcription Digital Collections Available Interviewee(s)/Speaker(s) OH# Family memories: Albert Manucy, Mark Manucy, Ann Day N/A No Manucy, and Gonzalez (the cat) OH21 N/A No James Manucy OH22 N/A No Elizabeth Archer Manucy OH23-OH27 N/A No The Archer Family/Charleston Manucys OH28 N/A No The Charles. D. Segui Family OH29 N/A No Charles I. Ortegas OH30 N/A No Alton Jerome "John" Westbrook OH31 High School Class of 1923: Arthur A. Manucy, Worth N/A No Gaines, and Marjorie Lindscott Gaines OH32 N/A No Arthur Manucy OH33-OH35 N/A No X. L. Pellicer OH36 Sundry St. Augustinians Yes J. (John) Carver Harris OH37 Sundry St. Augustinians Yes Joseph P. McAloon OH38 Sundry St. Augustinians Yes Haynes Grant, Sr. OH39 2 Revised Nov 2020 NMD Oral History Index Transcription Digital Collections Available Interviewee(s)/Speaker(s) OH# Oral History Programs Yes Talk of the Town - Margaret Manford OH40 Sundry St. Augustinians Yes Major Argrett OH41 N/A No David Benjamin "D. B." Green OH42-OH43 Sundry St. Augustinians Yes Florence Clements Samuels OH44 Sundry St. Augustinians Yes Charles Colee OH45-OH46 N/A No Earl Masters OH47 3 Revised Nov 2020 NMD Oral History Index Transcription Digital Collections Available Interviewee(s)/Speaker(s) OH# Sundry St. -

FY 2015 ‐2019 Transportation Improvement Program (TIP)

EXHIBIT B 2014-2018 Annual Update to the Five-Year Schedule of Capital Improvements FL-AL TPO FY 2015-2019 TIP FY 2015 ‐2019 Transportation Improvement Program (TIP) Adopted: June 11, 2014 Amended: September 10, 2014 “…planning for the future transportation needs of the Pensacola FL-AL Urbanized Area…” For information regarding this document, please contact: Gary Kramer TPO Staff/WFRPC Senior Transportation Planner [email protected] Staff to the TPO 4081 East Olive Road Suite A Pensacola, FL 32514 Telephone – 1-800-226-8914 Fax - 850-637-1923 “The preparation of this report has been financed in part through grant[s] from the Federal Highway Administration and Federal Transit Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation, under the State Planning and Research Program, Section 505 [or Metropolitan Planning Program, Section 104(f)] of Title 23, U.S. Code. The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the official views or policy of the U.S. Department of Transportation." Public participation is solicited without regard to race, color, national origin, sex, age, religion, disability or family status. Persons who require special accommodations under the Americans with Disabilities Act or those requiring language translations services (free of charge) should contact Brandi Whitehurst at (850) 332-7976 or (1-800-995-8771 for TTY- Florida) or by email at [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary Resolution 14-10 5 Year Summary by Fund Code Section 1 - Bridge Section 2 - Capacity Section 3 - Bike/ Pedestrian