Xenophon's Funeral Oration Near the Center of the Memorabilia (3.5)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

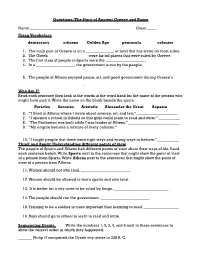

Questions: the Story of Ancient Greece and Rome

Questions: The Story of Ancient Greece and Rome Name ______________________________________________ Class _____ Using Vocabulary democracy citizens Golden Age peninsula colonies 1. The main part of Greece is on a ______________, or land that has water on most sides. 2. The Greek ____________________ were far-off places that were ruled by Greece. 3. The first class of people in Sparta were the ____________________. 4. In a ____________________ the government is run by the people. 5. The people of Athens enjoyed peace, art, and good government during Greece’s ____________________________. Who Am I? Read each sentence then look at the words in the word bank for the name of the person who might have said it. Write the name on the blank beside the quote. Pericles Socrates Aristotle Alexander the Great Aspasia 6. “I lived in Athens where I wrote about science, art, and law.” _____________________ 7. “I opened a school in Athens so that girls could learn to read and write.” ___________ 8. “The Parthenon was built while I was leader of Athens.” __________________________ 9. “My empire became a mixture of many cultures.” _______________________________ 10.“I taught people that there were right ways and wrong ways to behave.” ___________ Think and Apply: Understanding different points of view The people of Sparta and Athens had different points of view about their ways of life. Read each sentence below. Write Sparta next to the sentences that might show the point of view of a person from Sparta. Write Athens next to the sentences that might show the point of view of a person from Athens. -

Feminist Revisionary Histories of Rhetoric: Aspasia's Story

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work Spring 5-1999 Feminist Revisionary Histories of Rhetoric: Aspasia's Story Amy Suzanne Lawless University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Recommended Citation Lawless, Amy Suzanne, "Feminist Revisionary Histories of Rhetoric: Aspasia's Story" (1999). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/322 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY HONORS PROGRAM SENIOR PROJECT - APPROVAL N a me: _ dm~ - .l..4ul ~ ___________ ---------------------------- College: ___ M..5...~-~_ Department: ___(gI1~~~ -$!7;.h2j~~ ----- Faculty Mentor: ___lIs ...!_)Au~! _ ..A±~:JJ-------------------------- PROJECT TITLE: - __:fum~tU'it __ .&~\'?lP.0.:-L.!T __W-~~ · SS__ ~T__ Eb:b?L(k.!_ A; ' I -------------- ~~Jl~3-- -2b~1------------------------------ --------------------------------------------. _------------- I have reviewed this completed senior honors thesis with this student and certify that it is a project commensurate with honors -

1 Foreigners As Liberators: Education and Cultural Diversity in Plato's

1 Foreigners as Liberators: Education and Cultural Diversity in Plato’s Menexenus Rebecca LeMoine Assistant Professor of Political Science Florida Atlantic University NOTE: Use of this document is for private research and study only; the document may not be distributed further. The final manuscript has been accepted for publication and will appear in a revised form in The American Political Science Review 111.3 (August 2017). It is available for a FirstView online here: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055417000016 Abstract: Though recent scholarship challenges the traditional interpretation of Plato as anti- democratic, his antipathy to cultural diversity is still generally assumed. The Menexenus appears to offer some of the most striking evidence of Platonic xenophobia, as it features Socrates delivering a mock funeral oration that glorifies Athens’ exclusion of foreigners. Yet when readers play along with Socrates’ exhortation to imagine the oration through the voice of its alleged author Aspasia, Pericles’ foreign mistress, the oration becomes ironic or dissonant. Through this, Plato shows that foreigners can act as gadflies, liberating citizens from the intellectual hubris that occasions democracy’s fall into tyranny. In reminding readers of Socrates’ death, the dialogue warns, however, that fear of education may prevent democratic citizens from appreciating the role of cultural diversity in cultivating the virtue of Socratic wisdom. Keywords: Menexenus; Aspasia; cultural diversity; Socratic wisdom; Platonic irony Acknowledgments: An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2012 annual meeting of the Association for Political Theory, where it benefitted greatly from Susan Bickford’s insightful commentary. Thanks to Ethan Alexander-Davey, Andreas Avgousti, Richard Avramenko, Brendan Irons, Daniel Kapust, Michelle Schwarze, the APSR editorial team (both present and former), and four anonymous referees for their invaluable feedback on earlier drafts. -

8 Nickolas Pappas and Mark Zelcer What Might Philosophy Say At

��8 Book Reviews Nickolas Pappas and Mark Zelcer Politics and Philosophy in Plato’s Menexenus: Education and Rhetoric, Myth and History (London; New York: Routledge, 2015), vii + 236 pp. $140.00. ISBN 9781844658206 (hbk). What might philosophy say at the burial of citizens who died in war? No sooner is this timely question raised that we must acknowledge that it is far from obvious what the philosopher would say. Civic funerals are moments in political life where the philosopher is confronted by contingency, by a blow to the body politic of which she is part, where she must either speak or keep silent. The confrontation is the subject of Pappas and Zelcer’s book, Politics and Philosophy in Plato’s ‘Menexenus’. The couplings in its subtitle reveal the main ingredients of philosophic speech: Education and Rhetoric, Myth and History. The Menexenus, the authors write, ‘show[s] philosophy bringing a pedagogical impulse to funeral rhetoric that the Republic says philosophical rulers would bring to all aspects of governing a city’ (p. 99). Plato acknowledges the ‘magic of rhetoric’ (p. 136), and the relationship between philosophy and rhetoric is analogous to the relationship between philosophy and politics: in both cases philosophy is the superior partner and the driving force. For Plato, Pappas and Zelcer conclude, the dead are to be ‘buried in philosophy’ (p. 220). Since one cannot assume a ready familiarity with the Menexenus, here is a brief summary. Plato raises Socrates from the dead to converse with the young Menexenus, as the city is poised to commemorate those who died in Athens’ defeat at the end of the Corinthian War in 386 BC. -

Women and Property in Ancient Athens: a Discussion of the Private Orations and Menander Cheryl Cox University of Memphis

Women and Property in Ancient Athens: A Discussion of the Private Orations and Menander Cheryl Cox University of Memphis There has been a great deal of discussion in the past two decades or so among social historians and anthropologists of the proposition that women in European societies, both in the past and in the present, have informal power at the private level of the household. Women’s interests were reflected and expressed in succession practices and in the management of the household economy. Central to the status of women was the dowry because of its place in the conjugal household and the negotiations over its use and transmission. A large dowry ensured the woman’s important role in the decisions of the marital household and thus helped to stabilize the marriage. Because the dowry, as the property of the woman’s natal kin, would ideally be transmitted to the man’s children, the man could become involved in the property interests of his wife’s family of origin.1 In a material sense, in classical Athens the wife’s dowry allowed for the cohesion of two households (oikoi): the oikos of her marriage and that of her natal family. The dowry in legal terms belonged to the woman’s natal family, as it had to be returned to her family of origin either on divorce or on the death of her husband and her remarriage. Much of the information we have for dowries pertains to elite families. Because the woman’s dowry could be inherited by the children, it was worth fighting for, especially if she had not received her full share (Dem. -

Status of Women in Ancient Greece

Center for Open Access in Science ▪ https://www.centerprode.com/ojas.html Open Journal for Anthropological Studies, 2019, 3(2), 49-54. ISSN (Online) 2560-5348 ▪ https://doi.org/10.32591/coas.ojas.0302.03049s _________________________________________________________________________ Status of Women in Ancient Greece Zhulduz Amangelidyevna Seitkasimova M. Auezov South Kazakhstan State University, KAZAKHSTAN Faculty of Pedagogy and Culture, Shymkent Received 18 October 2019 ▪ Revised 12 December 2019 ▪ Accepted 21 December 2019 Abstract This paper examines the status, position and roles of women in ancient Greece. Based on available historical sources, it can be clearly established that women in ancient Greece had an inferior position to men. They were primarily viewed as “species-extending beings”. In none of the Greek city-states did women have political rights and were not considered as citizens. The status of women in ancient Greece, in terms of role, position, opportunity etc., varied from one city-state to another. This status is well known for ancient Athens, based on the large number of historical sources that can document the basic characteristics of the status of women in ancient Athens. Keywords: women’ status, ancient Greece, society, family, gender discrimination. 1. Introduction What was the status and positions of women in ancient Greece, and what was the main characteristics of that status? Women in the ancient Greek world had no possess all rights as men possessed and had few rights in comparison to male citizens. The key restrictions that women had was that they could not vote in different public affairs, and also could not own or inherit land. -

The Making of a Prostitute: Apollodoros's Portrait Of

Apollodoros’s Portrait of Neaira 161 THE MAKING OF A PROSTITUTE: APOLLODOROS’S PORTRAIT OF NEAIRA1 ALLISON GLAZEBROOK Apollodoros’s account of the life of Neaira ([Demosthenes] 59.16–49) is the most extensive narrative extant on a historical woman from the classical period. The recent publication of Debra Hamel’s book, Trying Neaira: The True Story of a Courtesan’s Scandalous Life in Ancient Greece (2003), has made the famous speech against Neaira and its recent scholarship accessible to a popular audience. The strength of Hamel’s work lies in the political, legal, and social context she provides for the speech, along with her ques- tioning of the various claims Apollodoros makes about Neaira’s “children” and her conclusion that he never proves beyond a doubt that Neaira has been acting as Stephanos’s wife. But does Apollodoros offer “the true story” of Neaira’s life as a courtesan, as Hamel’s title so boldly claims?2 The narrative detail of the speech and the testimony of witnesses convince Hamel (2003.156) that Apollodoros accurately portrays the events of Neaira’s early life. While one function of such witnesses was to attest to the veracity of a speaker’s comments, as in the modern day, their second 1A version of this paper was originally presented at the APA annual meeting in San Diego (2001). I would like to thank the audience for their lively discussion and helpful response, as well as Susan Cole, for her many suggestions, and my anonymous readers whose comments proved most fruitful. 2There is an assumption that oratory is a more objective source of evidence on women than other genres (Pomeroy 1975.x–xi). -

Alexander the Great and His Time (World Digital Library Edition)

BARNES & NOBLE mWorld Digital Library Alexander the Great Thomas N. Beck Agnes Savi BIOGRAPHY alexander the great alexander the great And His Time Agnes Savill Introduction by Thomas N. Beck Barnes & Noble World Digital Library New York This edition published by Barnes & Noble World Digital Library by arrangement with Barnes & Noble, Inc. Introduction Copyright © 2002 by Barnes & Noble World Digital Library All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Barnes & Noble World Digital Library, New York. Barnes & Noble World Digital Library and colophon are trademarks of Barnes & Noble.com. Barnes & Noble.com, 76 Ninth Avenue, New York, NY 10011. Cover Design by Red Canoe, Deer Lodge, TN ISBN 0-594-08113-0 introduction Alexander the Great. The very name conjures up images of the invincible conqueror in battle, arrows arcing across the sky, chariots thundering over the desert, swords clanging against shields, and the hand- some hero standing tall amidst the fray, slaying ene- mies by the score, and inspiring his men to triumph. Yet how much of this romantic notion is true, how much is myth, and what does it really matter to us anyway? Agnes Forbes Blackadder Savill, in her study of Alexander’s life (which was essentially one long cam- paign from Greece to India and part of the way back), argues that almost all of it is true despite its having passed into myth since the great man’s death. She also argues that it matters quite a bit to us — now more than ever, in fact. Considering the evil that one man could do, Savill wanted to show its polar oppo- site, to demonstrate that one man could change the world for the better; indeed, that one man in particu- lar had. -

Socrates' Aspasian Oration: the Play of Philosophy and Politics in Plato's

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Political Science Faculty Research and Scholarship Political Science 1993 Socrates' Aspasian Oration: The lP ay of Philosophy and Politics in Plato's Menexenus Stephen G. Salkever Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/polisci_pubs Part of the Ancient Philosophy Commons, and the Political Science Commons Custom Citation Salkever, Stephen G. "Socrates' Aspasian Oration: The lP ay of Philosophy and Politics in Plato's Menexenus." American Political Science Review 87 (1993): 133-143. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/polisci_pubs/12 For more information, please contact [email protected]. American Political Science Review Vol. 87, No. 1 March 1993 SOCRATES'ASPASIAN ORATION: THE PLAY OF PHILOSOPHY AND POLITICSIN PLATO'S MENEXENUS STEPHEN G. SALKEVER Bryn Mawr College P lato'sMenexenus is overlooked,perhaps because of thedifficulty of gauging its irony.In it, Socratesrecites a funeral orationhe says he learnedfrom Aspasia, describingevents that occurredafter the deathsof both Socratesand Pericles'mistress. But the dialogue'sironic complexityis one reasonit is a centralpart of Plato'spolitical philosophy. In bothstyle and substance, Menexenus rejectsthe heroicaccount of Atheniandemocracy proposed by Thucydides'Pericles, separatingAthenian citizenship from the questfor immortalglory; its pictureof the relationshipof philosopherto polis illustratesPlato's conception of the true politikos in the Statesman. In both dialogues,philosophic response to politicsis neitherdirect rule nor apoliticalwithdrawal. Menexe- nus presentsa Socrateswho influencespolitics indirectly, by recastingAthenian history and thus transformingthe termsin whichits politicalalternatives are conceived. -

Six Degrees of Alexander: Social Network Analysis As a Tool for Ancient History

Six Degrees of Alexander: Social Network Analysis as a Tool for Ancient History Diane Harris Cline Most academics are by now familiar with the concept of “six degrees of separation,” otherwise known as the “small-world effect,” popularized by Duncan Watts, Albert-Laszlo Barabasi, and Mark Buchanan.1 The basic idea is that “almost any pair of people in the world can be connected to one another by a short chain of intermediate acquaintances, of typical length about six,” as Mark Newman of the University of Michigan has put it in a recent review.2 Such degrees of separation come from the network of people in which an individual is embedded, ranging from their family to close friends to mere acquaintances. This type of social network is frequently discussed today in connection with Facebook, MySpace, and other recent phenomena associated with the Internet. The concept has also entered the domain of pop culture, as exemplified by the “Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon” game, in which participants attempt to link movie actors with Kevin Bacon based upon films in which each actor has appeared.3 Originally known as network theory or sometimes network analysis, Social Network Analysis (SNA), as it will be called here, began in part because of the ground-breaking study in 1967 by Stanley Milgram.4 Networks are entities of any kind linked together in some way. Social networks are people, or groups of people, linked together through social interaction. SNA has been used and applied successfully in a number of different fields, including sociology and business, not to mention international security, for decades—since at least the 1970s in most cases—but few ancient historians have made use of it to date. -

Alcibiades at the Crossroads: Philosophers, Courtesans and the Contest for a Young Man's Soul Nicholas C

Alcibiades at the Crossroads: Philosophers, Courtesans and the Contest for a Young Man's Soul Nicholas C. Rynearson (University of Georgia) Lucian’s Dialogues of the Courtesans 10 pits two courtesans, Chelidonion and Drosis, against a philosopher named Aristaenetus. At issue is a young man (meirakion), Cleinias, who has ceased visiting Drosis on the advice of Aristaenetus, with whom he now studies philosophy. A letter from Cleinias explains that his teacher forbids him to spend time with (suneinai) a courtesan because “it is far better to prefer virtue (aretê) to pleasure (hêdonê)” (10.3). Drosis attributes Aristaenetus’ prohibition to his own predatory desires, since he is a paiderastês, whose teaching is a pretext for “spending time with (suneinai) the handsomest youths” (10.4). Chelidonion suggests a fitting remedy: she will write “Aristaenetus is corrupting (diaphtheirei) Cleinias” on a wall in the Ceramicus, where Cleinias’ father often walks (10.4). Lucian’s playful dialogue thus closes with an echo of the trial and execution of Socrates for corruption of the youth. Similarly, in Alciphron’s Letters of the Courtesans 7, the hetaira Thaïs writes to her lover, Euthydemus, to complain that he ignores her now that he has taken up with a philosopher. “Do you think a philosopher (sophistês) is any better than a courtesan?,” she challenges (7.4), casting herself as the philosopher’s rival. She then adduces the example of Socrates and, like Chelidonion, recalls his trial and the charge of corruption: “Judge, if you want, between the hetaira Aspasia and the philosopher Socrates and consider which educated better men.