Athenian War Council

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CLIL Multikey Lesson Plan LESSON PLAN

CLIL MultiKey lesson plan LESSON PLAN Subject: Art History Topic: The Athenian acropolis Students' age: 14-15 Language level: B1 Time: 2 hours Content aims: Art History (and a bit of History) on ancient Greece and the poleis. To describe an artistic element of an ancient city To understand the political role of Art and Religion in Ancient Greece Language aims: - Listening activity - Learn and use new vocabulary - Knowledge of technical art and history vocabulary Pre-requisites: - Geographical and cartographical skill - Knowledge of Greek history from the Persian wars to Pericles; - The role of the city in the world Materials: - Personal computer - handouts Procedure steps: Teacher starts explaining the geographical asset: where is Greece in Europe, where is Athens, arriving to the map that shows the metropolis in the details. Then after a short brainstorming activity about the poleis, (birth and main characters) arrives to the substantial continuity of the word polis in English. Which are the words deriving from polis? acropolis, necropolis, metropolis, metropolitan; megalopolis, cosmopolitan; Politics Policy Police T. shows map and asks: 1 CLIL MultiKey lesson plan Where are the acropolis and the necropolis of Athens? Then t. shows a video, inviting students to understanding the following items: - Which was the Athenian political role? - Which politicians are quoted? Why? When do they live? - Which are the most relevant urban changes for Athens? Finally teacher invites students to complete the handout 2 CLIL MultiKey lesson plan HANDOUT a) Sites references: Image coins: http://www.ancientresource.com/lots/greek/coins_athens.html http://blogs-images.forbes.com/stephenpope/files/2011/05/300px-1_euro_coin_Gr_serie_1.png Athena's birth: http://galeri7.uludagsozluk.com/282/zeus_454246.png b) vvideos's transcripts 1) https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ancient-art-civilizations/greek-art/classical/v/parthenon Transcript Voiceover: We're looking at the Parthenon. -

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

10. Rood, Thucydides and His Predecessors 230-267

Histos () - THUCYDIDES AND HIS PREDECESSORS Thucydides’ response to his literary predecessors has been explored with some frequency in recent years. Several articles have appeared even since Simon Hornblower recently wrote that ‘two areas needing more work are Thucydides’ detailed intertextual relation to Homer and to Herodotus’. In these discussions, Thucydides tends to be seen as inheriting a wide range of specific narrative techniques from Homer, and as alluding to particular pas- sages in epic through the use of epic terms and through the broader struc- turing of his story. It has also been stressed that Thucydides’ relationship with Homer should be studied in the light of the pervasive Homeric charge found in the work of Herodotus, the greatest historian before Thucydides. Nor is Thucydides’ debt to Herodotus merely a matter of his taking over Herodotus’ Homeric features: it is seen, for instance, in his modelling of his Sicilian narrative after Herodotus’ account of the Persian Wars, and in his assuming knowledge of events described by Herodotus. Nonetheless, no apology is needed for making another contribution to this topic: by drawing together and examining some of the recent explora- tions of Thucydidean intertextuality, I hope to establish more firmly how Thucydides alluded to his predecessors; and by looking beyond the worlds of epic and Herodotus that have dominated recent discussions, I hope to present a more rounded image of the literary milieu of the early Greek his- torians. OCD (the conclusion to a survey, published in , of work on Thucydides since , when the second edition of the OCD was published). For an excellent general account of the importance of Homer for historiography, see H. -

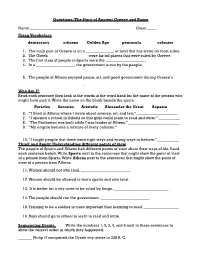

Questions: the Story of Ancient Greece and Rome

Questions: The Story of Ancient Greece and Rome Name ______________________________________________ Class _____ Using Vocabulary democracy citizens Golden Age peninsula colonies 1. The main part of Greece is on a ______________, or land that has water on most sides. 2. The Greek ____________________ were far-off places that were ruled by Greece. 3. The first class of people in Sparta were the ____________________. 4. In a ____________________ the government is run by the people. 5. The people of Athens enjoyed peace, art, and good government during Greece’s ____________________________. Who Am I? Read each sentence then look at the words in the word bank for the name of the person who might have said it. Write the name on the blank beside the quote. Pericles Socrates Aristotle Alexander the Great Aspasia 6. “I lived in Athens where I wrote about science, art, and law.” _____________________ 7. “I opened a school in Athens so that girls could learn to read and write.” ___________ 8. “The Parthenon was built while I was leader of Athens.” __________________________ 9. “My empire became a mixture of many cultures.” _______________________________ 10.“I taught people that there were right ways and wrong ways to behave.” ___________ Think and Apply: Understanding different points of view The people of Sparta and Athens had different points of view about their ways of life. Read each sentence below. Write Sparta next to the sentences that might show the point of view of a person from Sparta. Write Athens next to the sentences that might show the point of view of a person from Athens. -

Determining the Significance of Alliance Athologiesp in Bipolar Systems: a Case of the Peloponnesian War from 431-421 BCE

Wright State University CORE Scholar Browse all Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2016 Determining the Significance of Alliance athologiesP in Bipolar Systems: A Case of the Peloponnesian War from 431-421 BCE Anthony Lee Meyer Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all Part of the International Relations Commons Repository Citation Meyer, Anthony Lee, "Determining the Significance of Alliance Pathologies in Bipolar Systems: A Case of the Peloponnesian War from 431-421 BCE" (2016). Browse all Theses and Dissertations. 1509. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all/1509 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse all Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DETERMINING THE SIGNIFICANCE OF ALLIANCE PATHOLOGIES IN BIPOLAR SYSTEMS: A CASE OF THE PELOPONNESIAN WAR FROM 431-421 BCE A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts By ANTHONY LEE ISAAC MEYER Dual B.A., Russian Language & Literature, International Studies, Ohio State University, 2007 2016 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES ___April 29, 2016_________ I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Anthony Meyer ENTITLED Determining the Significance of Alliance Pathologies in Bipolar Systems: A Case of the Peloponnesian War from 431-421 BCE BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts. ____________________________ Liam Anderson, Ph.D. -

Feminist Revisionary Histories of Rhetoric: Aspasia's Story

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work Spring 5-1999 Feminist Revisionary Histories of Rhetoric: Aspasia's Story Amy Suzanne Lawless University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Recommended Citation Lawless, Amy Suzanne, "Feminist Revisionary Histories of Rhetoric: Aspasia's Story" (1999). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/322 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY HONORS PROGRAM SENIOR PROJECT - APPROVAL N a me: _ dm~ - .l..4ul ~ ___________ ---------------------------- College: ___ M..5...~-~_ Department: ___(gI1~~~ -$!7;.h2j~~ ----- Faculty Mentor: ___lIs ...!_)Au~! _ ..A±~:JJ-------------------------- PROJECT TITLE: - __:fum~tU'it __ .&~\'?lP.0.:-L.!T __W-~~ · SS__ ~T__ Eb:b?L(k.!_ A; ' I -------------- ~~Jl~3-- -2b~1------------------------------ --------------------------------------------. _------------- I have reviewed this completed senior honors thesis with this student and certify that it is a project commensurate with honors -

Applying Modern Immunology to the Plague of Ancient Athens

Pursuit - The Journal of Undergraduate Research at The University of Tennessee Volume 10 Issue 1 Article 7 May 2020 Applying Modern Immunology to the Plague of Ancient Athens Juhi C. Patel University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/pursuit Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Disease Modeling Commons, and the Epidemiology Commons Recommended Citation Patel, Juhi C. (2020) "Applying Modern Immunology to the Plague of Ancient Athens," Pursuit - The Journal of Undergraduate Research at The University of Tennessee: Vol. 10 : Iss. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/pursuit/vol10/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Volunteer, Open Access, Library Journals (VOL Journals), published in partnership with The University of Tennessee (UT) University Libraries. This article has been accepted for inclusion in Pursuit - The Journal of Undergraduate Research at The University of Tennessee by an authorized editor. For more information, please visit https://trace.tennessee.edu/pursuit. Applying Modern Immunology to the Plague of Ancient Athens Cover Page Footnote The author would like to thank Dr. Aleydis Van de Moortel at the University of Tennessee for research supervision and advice. This article is available in Pursuit - The Journal of Undergraduate Research at The University of Tennessee: https://trace.tennessee.edu/pursuit/vol10/iss1/7 1.1 Introduction. After the Persian wars in the early fifth century BC, Athens and Sparta had become two of the most powerful city-states in Greece. At first, they were allies against the common threat of the Persians. -

Euboea and Athens

Euboea and Athens Proceedings of a Colloquium in Memory of Malcolm B. Wallace Athens 26-27 June 2009 2011 Publications of the Canadian Institute in Greece Publications de l’Institut canadien en Grèce No. 6 © The Canadian Institute in Greece / L’Institut canadien en Grèce 2011 Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Euboea and Athens Colloquium in Memory of Malcolm B. Wallace (2009 : Athens, Greece) Euboea and Athens : proceedings of a colloquium in memory of Malcolm B. Wallace : Athens 26-27 June 2009 / David W. Rupp and Jonathan E. Tomlinson, editors. (Publications of the Canadian Institute in Greece = Publications de l'Institut canadien en Grèce ; no. 6) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-9737979-1-6 1. Euboea Island (Greece)--Antiquities. 2. Euboea Island (Greece)--Civilization. 3. Euboea Island (Greece)--History. 4. Athens (Greece)--Antiquities. 5. Athens (Greece)--Civilization. 6. Athens (Greece)--History. I. Wallace, Malcolm B. (Malcolm Barton), 1942-2008 II. Rupp, David W. (David William), 1944- III. Tomlinson, Jonathan E. (Jonathan Edward), 1967- IV. Canadian Institute in Greece V. Title. VI. Series: Publications of the Canadian Institute in Greece ; no. 6. DF261.E9E93 2011 938 C2011-903495-6 The Canadian Institute in Greece Dionysiou Aiginitou 7 GR-115 28 Athens, Greece www.cig-icg.gr THOMAS G. PALAIMA Euboea, Athens, Thebes and Kadmos: The Implications of the Linear B References 1 The Linear B documents contain a good number of references to Thebes, and theories about the status of Thebes among Mycenaean centers have been prominent in Mycenological scholarship over the last twenty years.2 Assumptions about the hegemony of Thebes in the Mycenaean palatial period, whether just in central Greece or over a still wider area, are used as the starting point for interpreting references to: a) Athens: There is only one reference to Athens on a possibly early tablet (Knossos V 52) as a toponym a-ta-na = Ἀθήνη in the singular, as in Hom. -

1 Foreigners As Liberators: Education and Cultural Diversity in Plato's

1 Foreigners as Liberators: Education and Cultural Diversity in Plato’s Menexenus Rebecca LeMoine Assistant Professor of Political Science Florida Atlantic University NOTE: Use of this document is for private research and study only; the document may not be distributed further. The final manuscript has been accepted for publication and will appear in a revised form in The American Political Science Review 111.3 (August 2017). It is available for a FirstView online here: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055417000016 Abstract: Though recent scholarship challenges the traditional interpretation of Plato as anti- democratic, his antipathy to cultural diversity is still generally assumed. The Menexenus appears to offer some of the most striking evidence of Platonic xenophobia, as it features Socrates delivering a mock funeral oration that glorifies Athens’ exclusion of foreigners. Yet when readers play along with Socrates’ exhortation to imagine the oration through the voice of its alleged author Aspasia, Pericles’ foreign mistress, the oration becomes ironic or dissonant. Through this, Plato shows that foreigners can act as gadflies, liberating citizens from the intellectual hubris that occasions democracy’s fall into tyranny. In reminding readers of Socrates’ death, the dialogue warns, however, that fear of education may prevent democratic citizens from appreciating the role of cultural diversity in cultivating the virtue of Socratic wisdom. Keywords: Menexenus; Aspasia; cultural diversity; Socratic wisdom; Platonic irony Acknowledgments: An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2012 annual meeting of the Association for Political Theory, where it benefitted greatly from Susan Bickford’s insightful commentary. Thanks to Ethan Alexander-Davey, Andreas Avgousti, Richard Avramenko, Brendan Irons, Daniel Kapust, Michelle Schwarze, the APSR editorial team (both present and former), and four anonymous referees for their invaluable feedback on earlier drafts. -

Athens Guide

ATHENS GUIDE Made by Dorling Kindersley 27. May 2010 PERSONAL GUIDES POWERED BY traveldk.com 1 Top 10 Athens guide Top 10 Acropolis The temples on the “Sacred Rock” of Athens are considered the most important monuments in the Western world, for they have exerted more influence on our architecture than anything since. The great marble masterpieces were constructed during the late 5th-century BC reign of Perikles, the Golden Age of Athens. Most were temples built to honour Athena, the city’s patron goddess. Still breathtaking for their proportion and scale, both human and majestic, the temples were adorned with magnificent, dramatic sculptures of the gods. Herodes Atticus Theatre Top 10 Sights 9 A much later addition, built in 161 by its namesake. Acropolis Rock In summer it hosts the Athens Festival (see Festivals 1 As the highest part of the city, the rock is an ideal and Events). place for refuge, religion and royalty. The Acropolis Rock has been used continuously for these purposes since Dionysus Theatre Neolithic times. 10 This mosaic-tiled theatre was the site of Classical Greece’s drama competitions, where the tragedies and Propylaia comedies by the great playwrights (Aeschylus, 2 At the top of the rock, you are greeted by the Sophocles, Euripides) were first performed. The theatre Propylaia, the grand entrance through which all visitors seated 15,000, and you can still see engraved front-row passed to reach the summit temples. marble seats, reserved for priests of Dionysus. Temple of Athena Nike (“Victory”) 3 There has been a temple to a goddess of victory at New Acropolis Museum this location since prehistoric times, as it protects and stands over the part of the rock most vulnerable to The Glass Floor enemy attack. -

8 Nickolas Pappas and Mark Zelcer What Might Philosophy Say At

��8 Book Reviews Nickolas Pappas and Mark Zelcer Politics and Philosophy in Plato’s Menexenus: Education and Rhetoric, Myth and History (London; New York: Routledge, 2015), vii + 236 pp. $140.00. ISBN 9781844658206 (hbk). What might philosophy say at the burial of citizens who died in war? No sooner is this timely question raised that we must acknowledge that it is far from obvious what the philosopher would say. Civic funerals are moments in political life where the philosopher is confronted by contingency, by a blow to the body politic of which she is part, where she must either speak or keep silent. The confrontation is the subject of Pappas and Zelcer’s book, Politics and Philosophy in Plato’s ‘Menexenus’. The couplings in its subtitle reveal the main ingredients of philosophic speech: Education and Rhetoric, Myth and History. The Menexenus, the authors write, ‘show[s] philosophy bringing a pedagogical impulse to funeral rhetoric that the Republic says philosophical rulers would bring to all aspects of governing a city’ (p. 99). Plato acknowledges the ‘magic of rhetoric’ (p. 136), and the relationship between philosophy and rhetoric is analogous to the relationship between philosophy and politics: in both cases philosophy is the superior partner and the driving force. For Plato, Pappas and Zelcer conclude, the dead are to be ‘buried in philosophy’ (p. 220). Since one cannot assume a ready familiarity with the Menexenus, here is a brief summary. Plato raises Socrates from the dead to converse with the young Menexenus, as the city is poised to commemorate those who died in Athens’ defeat at the end of the Corinthian War in 386 BC. -

Thucydides, Sicily, and the Defeat of Athens Tim Rood

Thucydides, Sicily, and the Defeat of Athens Tim Rood To cite this version: Tim Rood. Thucydides, Sicily, and the Defeat of Athens. KTÈMA Civilisations de l’Orient, de la Grèce et de Rome antiques, Université de Strasbourg, 2017, 42, pp.19-39. halshs-01670082 HAL Id: halshs-01670082 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01670082 Submitted on 21 Dec 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Les interprétations de la défaite de 404 Edith Foster Interpretations of Athen’s defeat in the Peloponnesian war ............................................................. 7 Edmond LÉVY Thucydide, le premier interprète d’une défaite anormale ................................................................. 9 Tim Rood Thucydides, Sicily, and the Defeat of Athens ...................................................................................... 19 Cinzia Bearzot La συμφορά de la cité La défaite d’Athènes (405-404 av. J.-C.) chez les orateurs attiques .................................................. 41 Michel Humm Rome, une « cité grecque