The Making of a Prostitute: Apollodoros's Portrait Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

Sviatoslav Dmitriev the Theoric Fund, the Athenian Finance in the 330S

Sviatoslav Dmitriev The Theoric Fund, the Athenian fi nance in the 330s, and Apollodorus Abstract This article examines the history and role of the Theoric Fund in Athens, focusing on evidence and arguments in the long-running debate about whether a legal prohibition existed against channeling the surplus budget money designated for the Theoric Fund to military purposes. The argument here is that Libanius’ reference to this prohibition as being enforced by the death penalty for at least some time in the 340s cannot simply be rejected by adducing the evidence about either the proposal to have a public vote on diverting this money for military purposes, as was moved by Apollodorus in the early 340s, or the way in which the Theoric Fund operated in the 330s and 320s. Quite a lot has been written about the Theoric Fund, whose main declared purpose was to distribute money for public entertainment to qualifi ed Athe- nians, primarily for two reasons: the contested dating of its establishment, and the uncertainty about whether there existed a prohibition on diverting its money for other purposes. The foundation of the Theoric Fund is variously attributed to Pericles, to Agyrrhius in the early fourth century, or, according to the ma- jority opinion, to Diophantus and Eubulus in the mid-350s.1 Pinpointing the exact date of its establishment might not be as important as some think, since it is likely that the Fund, and the very idea of fi nancing public entertainment, evolved over time, paralleling the progress of Athenian democracy, which is 1 Pericles: Schol. -

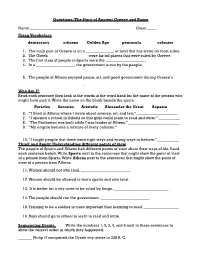

Questions: the Story of Ancient Greece and Rome

Questions: The Story of Ancient Greece and Rome Name ______________________________________________ Class _____ Using Vocabulary democracy citizens Golden Age peninsula colonies 1. The main part of Greece is on a ______________, or land that has water on most sides. 2. The Greek ____________________ were far-off places that were ruled by Greece. 3. The first class of people in Sparta were the ____________________. 4. In a ____________________ the government is run by the people. 5. The people of Athens enjoyed peace, art, and good government during Greece’s ____________________________. Who Am I? Read each sentence then look at the words in the word bank for the name of the person who might have said it. Write the name on the blank beside the quote. Pericles Socrates Aristotle Alexander the Great Aspasia 6. “I lived in Athens where I wrote about science, art, and law.” _____________________ 7. “I opened a school in Athens so that girls could learn to read and write.” ___________ 8. “The Parthenon was built while I was leader of Athens.” __________________________ 9. “My empire became a mixture of many cultures.” _______________________________ 10.“I taught people that there were right ways and wrong ways to behave.” ___________ Think and Apply: Understanding different points of view The people of Sparta and Athens had different points of view about their ways of life. Read each sentence below. Write Sparta next to the sentences that might show the point of view of a person from Sparta. Write Athens next to the sentences that might show the point of view of a person from Athens. -

Feminist Revisionary Histories of Rhetoric: Aspasia's Story

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work Spring 5-1999 Feminist Revisionary Histories of Rhetoric: Aspasia's Story Amy Suzanne Lawless University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Recommended Citation Lawless, Amy Suzanne, "Feminist Revisionary Histories of Rhetoric: Aspasia's Story" (1999). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/322 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY HONORS PROGRAM SENIOR PROJECT - APPROVAL N a me: _ dm~ - .l..4ul ~ ___________ ---------------------------- College: ___ M..5...~-~_ Department: ___(gI1~~~ -$!7;.h2j~~ ----- Faculty Mentor: ___lIs ...!_)Au~! _ ..A±~:JJ-------------------------- PROJECT TITLE: - __:fum~tU'it __ .&~\'?lP.0.:-L.!T __W-~~ · SS__ ~T__ Eb:b?L(k.!_ A; ' I -------------- ~~Jl~3-- -2b~1------------------------------ --------------------------------------------. _------------- I have reviewed this completed senior honors thesis with this student and certify that it is a project commensurate with honors -

1 Foreigners As Liberators: Education and Cultural Diversity in Plato's

1 Foreigners as Liberators: Education and Cultural Diversity in Plato’s Menexenus Rebecca LeMoine Assistant Professor of Political Science Florida Atlantic University NOTE: Use of this document is for private research and study only; the document may not be distributed further. The final manuscript has been accepted for publication and will appear in a revised form in The American Political Science Review 111.3 (August 2017). It is available for a FirstView online here: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055417000016 Abstract: Though recent scholarship challenges the traditional interpretation of Plato as anti- democratic, his antipathy to cultural diversity is still generally assumed. The Menexenus appears to offer some of the most striking evidence of Platonic xenophobia, as it features Socrates delivering a mock funeral oration that glorifies Athens’ exclusion of foreigners. Yet when readers play along with Socrates’ exhortation to imagine the oration through the voice of its alleged author Aspasia, Pericles’ foreign mistress, the oration becomes ironic or dissonant. Through this, Plato shows that foreigners can act as gadflies, liberating citizens from the intellectual hubris that occasions democracy’s fall into tyranny. In reminding readers of Socrates’ death, the dialogue warns, however, that fear of education may prevent democratic citizens from appreciating the role of cultural diversity in cultivating the virtue of Socratic wisdom. Keywords: Menexenus; Aspasia; cultural diversity; Socratic wisdom; Platonic irony Acknowledgments: An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2012 annual meeting of the Association for Political Theory, where it benefitted greatly from Susan Bickford’s insightful commentary. Thanks to Ethan Alexander-Davey, Andreas Avgousti, Richard Avramenko, Brendan Irons, Daniel Kapust, Michelle Schwarze, the APSR editorial team (both present and former), and four anonymous referees for their invaluable feedback on earlier drafts. -

St John's Smith Square

ST JOHN’S SMITH SQUARE 2015/16 SEASON Discover a musical landmark Patron HRH The Duchess of Cornwall 2015/16 SEASON CONTENTS WELCOME TO ST JOHN’S SMITH SQUARE —— —— 01 Welcome 102 School concerts Whether you’re already a friend, or As renovation begins at Southbank 02 Season Overview 105 Discover more discovering us for the first time, I trust Centre, we welcome residencies from the 02 Orchestral Performance 106 St John’s history you’ll enjoy a rewarding and stimulating Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment 03 Choral & Vocal Music 108 Join us experience combining inspirational and London Sinfonietta, world-class 03 Opera 109 Subscription packages music, delicious food and good company performers from their International Piano 04 Period Instruments 110 Booking information in the fabulous grandeur of this historic Series and International Chamber Music 05 Regular Series 111 How to find us building – the UK’s only baroque Series, and a mid-summer performance 06 New Music 112 Footstool Restaurant concert venue. from the Philharmonia Orchestra. 07 Young Artists’ Scheme This is our first annual season brochure We’re proud of our reputation for quality 08 Festivals – a season that features more than 250 and friendly service, and welcome the 09 Southbank Centre concerts, numerous world premieres and thoughts of our visitors. So, if you have 10 Listings countless talented musicians. We’re also any comments, please let me know and discussing further exciting projects, so I’ll gladly discuss them with you. please keep an eye on our What’s On I look forward to welcoming you to guides or sign up to our e-newsletter. -

Arcana Mundi : Magic and the Occult in the Greek and Roman Worlds : a Collection of Ancient Texts / Translated, Annotated, and Introduced by Georg Luck

o`o`o`o`o`o SECOND EDITION Arcana Mundi MAGIC AND THE OCCULT IN THE GREEK AND ROMAN WORLDS A Collection of Ancient Texts Translated, Annotated, and Introduced by Georg Luck o`o`o`o`o`o THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS BALTIMORE The first edition of this book was brought to publication with the generous assistance of the David M. Robinson Fund and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. ∫ 1985, 2006 The Johns Hopkins University Press All rights reserved. Published 1985, 2006 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1 The Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363 www.press.jhu.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Arcana mundi : magic and the occult in the Greek and Roman worlds : a collection of ancient texts / translated, annotated, and introduced by Georg Luck. — 2nd ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and indexes. isbn 0-8018-8345-8 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 0-8018-8346-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Occultism—Greece—History—Sources. 2. Occultism—Rome—History— Sources. 3. Civilization, Classical—Sources. I. Luck, Georg, 1926– bf1421.a73 2006 130.938—dc22 2005028354 A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. For Harriet This page intentionally left blank Contents List of Texts ix Preface xiii List of Abbreviations xvii General Introduction: Exploring Ancient Magic 1 I. MAGIC Introduction 33 Texts 93 II. MIRACLES Introduction 177 Texts 185 III. DAEMONOLOGY Introduction 207 Texts 223 IV. DIVINATION Introduction 285 Texts 321 V. -

8 Nickolas Pappas and Mark Zelcer What Might Philosophy Say At

��8 Book Reviews Nickolas Pappas and Mark Zelcer Politics and Philosophy in Plato’s Menexenus: Education and Rhetoric, Myth and History (London; New York: Routledge, 2015), vii + 236 pp. $140.00. ISBN 9781844658206 (hbk). What might philosophy say at the burial of citizens who died in war? No sooner is this timely question raised that we must acknowledge that it is far from obvious what the philosopher would say. Civic funerals are moments in political life where the philosopher is confronted by contingency, by a blow to the body politic of which she is part, where she must either speak or keep silent. The confrontation is the subject of Pappas and Zelcer’s book, Politics and Philosophy in Plato’s ‘Menexenus’. The couplings in its subtitle reveal the main ingredients of philosophic speech: Education and Rhetoric, Myth and History. The Menexenus, the authors write, ‘show[s] philosophy bringing a pedagogical impulse to funeral rhetoric that the Republic says philosophical rulers would bring to all aspects of governing a city’ (p. 99). Plato acknowledges the ‘magic of rhetoric’ (p. 136), and the relationship between philosophy and rhetoric is analogous to the relationship between philosophy and politics: in both cases philosophy is the superior partner and the driving force. For Plato, Pappas and Zelcer conclude, the dead are to be ‘buried in philosophy’ (p. 220). Since one cannot assume a ready familiarity with the Menexenus, here is a brief summary. Plato raises Socrates from the dead to converse with the young Menexenus, as the city is poised to commemorate those who died in Athens’ defeat at the end of the Corinthian War in 386 BC. -

Sacred Mushrooms of the Goddess and the Secrets of Eleusis

In memory of Blaise Daniel Staples, my companion and soul mate. He is dearly missed. PREFACE by Huston Smith WHEN I WAS ABOUT TO PUBLISH Cleansing the Doors of Perception: The Religious Significance of Entheogenic Plants and Chemicals, there were those who advised me not to do so, saying that it would destroy my reputation. Time has proved them wrong. As the religious significance of these substances comes to be increasingly accepted—the glaring exception being the Food and Drug Administration—the sales of that book (favorably reviewed from the beginning) continue to rise. As does my conviction of the importance of the issue, and I will say why. The great achievement of the linguist Noam Chomsky, who was my colleague during the fifteen years I taught at MIT, was to discover the universal grammar that every spoken language–– English, Chinese, French, whatever––must conform to, for it seems to be imprinted into the human brain. I, for my part, have worked out the universal grammar of religion to which authentic religions conform. Reduced to a single sentence, that grammar concludes that Reality is Perfect, and that human beings should do their best to conform their lives to that perfection. Reality’s perfection seems to be contradicted by perception of the world, but this is not surprising, for Reality is Infinite and our minds are not. Out minds must expand if they are to receive even glimpses of the Infinite Perfection. Thus the question is: how can they do this? Perfect Reality has provided a way. Through the entheogens, to be sure, but here we come to a point that has been under-noticed in the discussion of this important subject. -

Orthoptera : Gryllidae) of the World

ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF OECANTHINAE (ORTHOPTERA : GRYLLIDAE) OF THE WORLD THOMASJ. WALKER Department of Entomology, University of Florida, Gainesville The most recent listing of the Oecanthinae of the world is in Volume 2 of Kirby's Syno.nymic Catalogtie of Orthopte~a(1906, p. 72-76). Since then the number of described species has doubled and studies of the spe- cies in Africa (Chopard 1932), the United States (T. Walker 1962a, 1963), and Latin America (T. Walker 1967) have revealed new synonymies. The list below sumniarizes present knowledge of oecanthine taxonomy, nornen- clature, and geographic distribution. Keys to the species of Oecanthinae in specific areas are in the studies listed above and in Tarbinsky (1932, USSR), Chopard (1936, Ceylon), and Chopard (1951, Australia). Little has been published on the biology of Oecanthinae with the exception of Oecaizthlts pellzlcens of Europe (Chopard 1938, M.-C. Busnel 1954, M.-C. and R.-G. Busnel 1954) and various U. S. species (Fulton 1915, 1925, 1926a, 1926b; T. Walker 1957, 1962a, 196213, 1963). The following conventions are used in the checkl~st: After the word Type, a single asterisk ( ) means that the condition and place of deposit of the type specimen were confirmed by correspondence. A double asterisk (' ') means that I have examined the type specimen. Data concerning the present status of the type specimen are separated by a semi-colon from data on the place and date of collection and the collector. Abbreviations are used for the following museums: Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (ANSP) ; British Nuseum (Nat. Hist.), Lon- don, England (BM); Universitetets Zoologiske Museum, Copenhagen, Den- mark (Copenhngen) ; Museum d'Histoire Naturelle, Genhve, Switzerland (Gmzi.ce) ; Museum Nattonal d'Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France (Paris) ; Naturhistoriska Riksmuseum, Stockholm, Sweden (Stocliholnz) ; Universi- ty of Michigan Museum of Zoology, Ann Arbor, Michigan (UMMZ); United States National hlluseum, Washington, D. -

Women and Property in Ancient Athens: a Discussion of the Private Orations and Menander Cheryl Cox University of Memphis

Women and Property in Ancient Athens: A Discussion of the Private Orations and Menander Cheryl Cox University of Memphis There has been a great deal of discussion in the past two decades or so among social historians and anthropologists of the proposition that women in European societies, both in the past and in the present, have informal power at the private level of the household. Women’s interests were reflected and expressed in succession practices and in the management of the household economy. Central to the status of women was the dowry because of its place in the conjugal household and the negotiations over its use and transmission. A large dowry ensured the woman’s important role in the decisions of the marital household and thus helped to stabilize the marriage. Because the dowry, as the property of the woman’s natal kin, would ideally be transmitted to the man’s children, the man could become involved in the property interests of his wife’s family of origin.1 In a material sense, in classical Athens the wife’s dowry allowed for the cohesion of two households (oikoi): the oikos of her marriage and that of her natal family. The dowry in legal terms belonged to the woman’s natal family, as it had to be returned to her family of origin either on divorce or on the death of her husband and her remarriage. Much of the information we have for dowries pertains to elite families. Because the woman’s dowry could be inherited by the children, it was worth fighting for, especially if she had not received her full share (Dem. -

Status of Women in Ancient Greece

Center for Open Access in Science ▪ https://www.centerprode.com/ojas.html Open Journal for Anthropological Studies, 2019, 3(2), 49-54. ISSN (Online) 2560-5348 ▪ https://doi.org/10.32591/coas.ojas.0302.03049s _________________________________________________________________________ Status of Women in Ancient Greece Zhulduz Amangelidyevna Seitkasimova M. Auezov South Kazakhstan State University, KAZAKHSTAN Faculty of Pedagogy and Culture, Shymkent Received 18 October 2019 ▪ Revised 12 December 2019 ▪ Accepted 21 December 2019 Abstract This paper examines the status, position and roles of women in ancient Greece. Based on available historical sources, it can be clearly established that women in ancient Greece had an inferior position to men. They were primarily viewed as “species-extending beings”. In none of the Greek city-states did women have political rights and were not considered as citizens. The status of women in ancient Greece, in terms of role, position, opportunity etc., varied from one city-state to another. This status is well known for ancient Athens, based on the large number of historical sources that can document the basic characteristics of the status of women in ancient Athens. Keywords: women’ status, ancient Greece, society, family, gender discrimination. 1. Introduction What was the status and positions of women in ancient Greece, and what was the main characteristics of that status? Women in the ancient Greek world had no possess all rights as men possessed and had few rights in comparison to male citizens. The key restrictions that women had was that they could not vote in different public affairs, and also could not own or inherit land.