Six Degrees of Alexander: Social Network Analysis As a Tool for Ancient History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alexander the Great and Hephaestion

2019-3337-AJHIS-HIS 1 Alexander the Great and Hephaestion: 2 Censorship and Bisexual Erasure in Post-Macedonian 3 Society 4 5 6 Same-sex relations were common in ancient Greece and having both male and female 7 physical relationships was a cultural norm. However, Alexander the Great is almost 8 always portrayed in modern depictions as heterosexual, and the disappearance of his 9 life-partner Hephaestion is all but complete in ancient literature. Five full primary 10 source biographies of Alexander have survived from antiquity, making it possible to 11 observe the way scholars, popular writers and filmmakers from the Victorian era 12 forward have interpreted this evidence. This research borrows an approach from 13 gender studies, using the phenomenon of bisexual erasure to contribute a new 14 understanding for missing information regarding the relationship between Alexander 15 and his life-partner Hephaestion. In Greek and Macedonian society, pederasty was the 16 norm, and boys and men did not have relations with others of the same age because 17 there was almost always a financial and power difference. Hephaestion was taller and 18 more handsome than Alexander, so it might have appeared that he held the power in 19 their relationship. The hypothesis put forward here suggests that writers have erased 20 the sexual partnership between Alexander and Hephaestion because their relationship 21 did not fit the norm of acceptable pederasty as practiced in Greek and Macedonian 22 culture or was no longer socially acceptable in the Roman contexts of the ancient 23 historians. Ancient biographers may have conducted censorship to conceal any 24 implication of femininity or submissiveness in this relationship. -

Royal Power, Law and Justice in Ancient Macedonia Joseph Roisman

Royal Power, Law and Justice in Ancient Macedonia Joseph Roisman In his speech On the Crown Demosthenes often lionizes himself by suggesting that his actions and policy required him to overcome insurmountable obstacles. Thus he contrasts Athens’ weakness around 346 B.C.E. with Macedonia’s strength, and Philip’s II unlimited power with the more constrained and cumbersome decision-making process at home, before asserting that in spite of these difficulties he succeeded in forging later a large Greek coalition to confront Philip in the battle of Chaeronea (Dem.18.234–37). [F]irst, he (Philip) ruled in his own person as full sovereign over subservient people, which is the most important factor of all in waging war . he was flush with money, and he did whatever he wished. He did not announce his intentions in official decrees, did not deliberate in public, was not hauled into the courts by sycophants, was not prosecuted for moving illegal proposals, was not accountable to anyone. In short, he was ruler, commander, in control of everything.1 For his depiction of Philip’s authority Demosthenes looks less to Macedonia than to Athens, because what makes the king powerful in his speech is his freedom from democratic checks. Nevertheless, his observations on the Macedonian royal power is more informative and helpful than Aristotle’s references to it in his Politics, though modern historians tend to privilege the philosopher for what he says or even does not say on the subject. Aristotle’s seldom mentions Macedonian kings, and when he does it is for limited, exemplary purposes, lumping them with other kings who came to power through benefaction and public service, or who were assassinated by men they had insulted.2 Moreover, according to Aristotle, the extreme of tyranny is distinguished from ideal kingship (pambasilea) by the fact that tyranny is a government that is not called to account. -

Alexander's Seventh Phalanx Battalion Milns, R D Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Summer 1966; 7, 2; Proquest Pg

Alexander's Seventh Phalanx Battalion Milns, R D Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Summer 1966; 7, 2; ProQuest pg. 159 Alexander's Seventh Phalanx Battalion R. D. Milns SOME TIME between the battle of Gaugamela and the battle of A the Hydaspes the number of battalions in the Macedonian phalanx was raised from six to seven.1 This much is clear; what is not certain is when the new formation came into being. Berve2 believes that the introduction took place at Susa in 331 B.C. He bases his belief on two facts: (a) the arrival of 6,000 Macedonian infantry and 500 Macedonian cavalry under Amyntas, son of Andromenes, when the King was either near or at Susa;3 (b) the appearance of Philotas (not the son of Parmenion) as a battalion leader shortly afterwards at the Persian Gates.4 Tarn, in his discussion of the phalanx,5 believes that the seventh battalion was not created until 328/7, when Alexander was at Bactra, the new battalion being that of Cleitus "the White".6 Berve is re jected on the grounds: (a) that Arrian (3.16.11) says that Amyntas' reinforcements were "inserted into the existing (six) battalions KC1:TCt. e8vr(; (b) that Philotas has in fact taken over the command of Perdiccas' battalion, Perdiccas having been "promoted to the Staff ... doubtless after the battle" (i.e. Gaugamela).7 The seventh battalion was formed, he believes, from reinforcements from Macedonia who reached Alexander at Nautaca.8 Now all of Tarn's arguments are open to objection; and I shall treat them in the order they are presented above. -

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

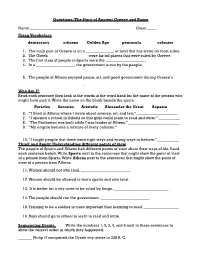

Questions: the Story of Ancient Greece and Rome

Questions: The Story of Ancient Greece and Rome Name ______________________________________________ Class _____ Using Vocabulary democracy citizens Golden Age peninsula colonies 1. The main part of Greece is on a ______________, or land that has water on most sides. 2. The Greek ____________________ were far-off places that were ruled by Greece. 3. The first class of people in Sparta were the ____________________. 4. In a ____________________ the government is run by the people. 5. The people of Athens enjoyed peace, art, and good government during Greece’s ____________________________. Who Am I? Read each sentence then look at the words in the word bank for the name of the person who might have said it. Write the name on the blank beside the quote. Pericles Socrates Aristotle Alexander the Great Aspasia 6. “I lived in Athens where I wrote about science, art, and law.” _____________________ 7. “I opened a school in Athens so that girls could learn to read and write.” ___________ 8. “The Parthenon was built while I was leader of Athens.” __________________________ 9. “My empire became a mixture of many cultures.” _______________________________ 10.“I taught people that there were right ways and wrong ways to behave.” ___________ Think and Apply: Understanding different points of view The people of Sparta and Athens had different points of view about their ways of life. Read each sentence below. Write Sparta next to the sentences that might show the point of view of a person from Sparta. Write Athens next to the sentences that might show the point of view of a person from Athens. -

Feminist Revisionary Histories of Rhetoric: Aspasia's Story

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work Spring 5-1999 Feminist Revisionary Histories of Rhetoric: Aspasia's Story Amy Suzanne Lawless University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Recommended Citation Lawless, Amy Suzanne, "Feminist Revisionary Histories of Rhetoric: Aspasia's Story" (1999). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/322 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY HONORS PROGRAM SENIOR PROJECT - APPROVAL N a me: _ dm~ - .l..4ul ~ ___________ ---------------------------- College: ___ M..5...~-~_ Department: ___(gI1~~~ -$!7;.h2j~~ ----- Faculty Mentor: ___lIs ...!_)Au~! _ ..A±~:JJ-------------------------- PROJECT TITLE: - __:fum~tU'it __ .&~\'?lP.0.:-L.!T __W-~~ · SS__ ~T__ Eb:b?L(k.!_ A; ' I -------------- ~~Jl~3-- -2b~1------------------------------ --------------------------------------------. _------------- I have reviewed this completed senior honors thesis with this student and certify that it is a project commensurate with honors -

1 Foreigners As Liberators: Education and Cultural Diversity in Plato's

1 Foreigners as Liberators: Education and Cultural Diversity in Plato’s Menexenus Rebecca LeMoine Assistant Professor of Political Science Florida Atlantic University NOTE: Use of this document is for private research and study only; the document may not be distributed further. The final manuscript has been accepted for publication and will appear in a revised form in The American Political Science Review 111.3 (August 2017). It is available for a FirstView online here: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055417000016 Abstract: Though recent scholarship challenges the traditional interpretation of Plato as anti- democratic, his antipathy to cultural diversity is still generally assumed. The Menexenus appears to offer some of the most striking evidence of Platonic xenophobia, as it features Socrates delivering a mock funeral oration that glorifies Athens’ exclusion of foreigners. Yet when readers play along with Socrates’ exhortation to imagine the oration through the voice of its alleged author Aspasia, Pericles’ foreign mistress, the oration becomes ironic or dissonant. Through this, Plato shows that foreigners can act as gadflies, liberating citizens from the intellectual hubris that occasions democracy’s fall into tyranny. In reminding readers of Socrates’ death, the dialogue warns, however, that fear of education may prevent democratic citizens from appreciating the role of cultural diversity in cultivating the virtue of Socratic wisdom. Keywords: Menexenus; Aspasia; cultural diversity; Socratic wisdom; Platonic irony Acknowledgments: An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2012 annual meeting of the Association for Political Theory, where it benefitted greatly from Susan Bickford’s insightful commentary. Thanks to Ethan Alexander-Davey, Andreas Avgousti, Richard Avramenko, Brendan Irons, Daniel Kapust, Michelle Schwarze, the APSR editorial team (both present and former), and four anonymous referees for their invaluable feedback on earlier drafts. -

Aus: Zeitschrift Für Papyrologie Und Epigraphik 87 (1991) 39–41 © Dr

W. HECKEL HEPHAISTON “THE ATHENIAN” aus: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 87 (1991) 39–41 © Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, Bonn 39 HEPHAISTION "THE ATHENIAN" IG ii2 405, a decree of Demades, records the granting of Athenian citizenship to a certain Amyntor son of Demetrios (Kirchner, PA 750) and his descendants in 334 B. C.: Dhmãdhw | [Dhm°ou Pa]i[a]nieÁw e‰pe|[n: §pain°sai] ÉAmÊntora, [§|peidØ eÎnoi]an §nde¤kn|[utai per‹ ÉAy]hna¤ouw, e‰|[nai dÉ ÉAmÊntor]a D[hm]htr¤o|[u ÉAyhna›on a]ÈtÚn ka‹ §k|[gÒnouw aÈto]Ë ...1 This man has, as far as I know, not been identified with any known historical individual. All we know about him is that he was a foreigner and that he performed some service to the Athenians which merited Demades’ proposal that he and his descendants receive citizenship. C. Schwenk (Athens in the Age of Alexander [Chicago 1985], 134), however, pre-empts one line of inquiry by arguing that "the appearance of Demades as proposer does not require that Amyntor be Macedonian or have Macedonian connections." Indeed not. But the names of both Amyntor and his father, Demetrios, do point strongly towards Macedonia, and it is tempting to see in Amyntor the father of Alexander’s boyhood friend Hephaistion. On the face of it, the connection is a tenuous one: Hephaistion’s father was named Amyntor (Arr. 6. 28. 4; Ind. 18. 3), but nothing is known of his career or family- background. Presumably, he belonged to the Macedonian aristocracy; for his son was educated by Aristotle along with Alexander (Curt. -

8 Nickolas Pappas and Mark Zelcer What Might Philosophy Say At

��8 Book Reviews Nickolas Pappas and Mark Zelcer Politics and Philosophy in Plato’s Menexenus: Education and Rhetoric, Myth and History (London; New York: Routledge, 2015), vii + 236 pp. $140.00. ISBN 9781844658206 (hbk). What might philosophy say at the burial of citizens who died in war? No sooner is this timely question raised that we must acknowledge that it is far from obvious what the philosopher would say. Civic funerals are moments in political life where the philosopher is confronted by contingency, by a blow to the body politic of which she is part, where she must either speak or keep silent. The confrontation is the subject of Pappas and Zelcer’s book, Politics and Philosophy in Plato’s ‘Menexenus’. The couplings in its subtitle reveal the main ingredients of philosophic speech: Education and Rhetoric, Myth and History. The Menexenus, the authors write, ‘show[s] philosophy bringing a pedagogical impulse to funeral rhetoric that the Republic says philosophical rulers would bring to all aspects of governing a city’ (p. 99). Plato acknowledges the ‘magic of rhetoric’ (p. 136), and the relationship between philosophy and rhetoric is analogous to the relationship between philosophy and politics: in both cases philosophy is the superior partner and the driving force. For Plato, Pappas and Zelcer conclude, the dead are to be ‘buried in philosophy’ (p. 220). Since one cannot assume a ready familiarity with the Menexenus, here is a brief summary. Plato raises Socrates from the dead to converse with the young Menexenus, as the city is poised to commemorate those who died in Athens’ defeat at the end of the Corinthian War in 386 BC. -

THE HELLENISTIC RULERS and THEIR POETS. SILENCING DANGEROUS CRITICS?* I the Beginning of the Reign of Ptolemy VII Euergetes II I

Originalveröffentlichung in: Ancient society 29.1998-99 (1998), S. 147-174 THE HELLENISTIC RULERS AND THEIR POETS. SILENCING DANGEROUS CRITICS?* i The beginning of the reign of Ptolemy VII Euergetes II in the year 145 bc following the death of his brother Ptolemy VI Philometor was described in a very negative way by ancient authors1. According to Athenaeus Ptolemy who ruled over Egypt... received from the Alexandrians appropriately the name of Malefactor. For he murdered many of the Alexandrians; not a few he sent into exile, and filled the islands and towns with men who had grown up with his brother — philologians, philosophers, mathematicians, musicians, painters, athletic trainers, physicians, and many other men of skill in their profession2. It is true that anecdotal tradition, as we find it here, is mostly of tenden tious origin, «but the course of the events suggests that the gossip-mon- * This article is the expanded version of a paper given on 2 November 1995, at the University of St Andrews, and — in a slightly changed version — on 3 November 1995, during the «Leeds Latin Seminar* on «Epigrams and Politics*. I would like to thank my colleagues there very much, especially Michael Whitby (now Warwick), for their invita tion, their hospitality, and stimulating discussions. Moreover, I would like to thank Jurgen Malitz (Eichstatt), Doris Meyer and Eckhard Wirbelauer (both Freiburg/Brsg.) for numer ous suggestions, Joachim Mathieu (Eichstatt/Atlanta) for the translation, and Roland G. Mayer (London) for his support in preparing the paper. 1 For biographical details cf. H. V olkmann , art. Ptolemaios VIII. -

Alexander the Not So Great William Baran Bill Ba

______________________________________________________________________________ Alexander the Not So Great William Baran Bill Baran, from Crystal Lake, Illinois, wrote "Alexander the Not So Great" during his senior year for Dr. Lee Patterson's Alexander the Great course in Fall 2015. He is currently a senior, majoring in history, and expects to graduate in May 2016. ______________________________________________________________________________ “It is perhaps Ptolemy who first coined the title ‘Great’ to describe Alexander, an epithet that has stayed with him to this day.”1 Whether or not this is true, somewhere along the way Alexander inherited the title “Great,” but is it one that he deserves? Alexander is responsible for expanding Macedonian territory significantly and it is something that he could not have accomplished alone. Since the backing of the army was crucial, why did some of Alexander’s generals not live past the life of Alexander? Although some of the generals and other army personnel inevitably died while in battle, others did not receive such a glorified death. Under Alexander’s rule numerous people in his army were murdered or died under suspicious circumstances. The death witnessed while Alexander ruled did not end there, because the army as a whole often suffered due to poor decision making on Alexander’s part. Whether direct or indirect Alexander ordered or caused the deaths of many because of anger, suspicion, or by poor choices. Alexander does not deserve the title “Great,” because of the deliberate killing under his command of both individuals and his army. Before embarking on the journey of tearing down Alexander’s title, it is important to understand the transition from Philip II to Alexander. -

The Anabasis of Alexander; Or, the History of the Wars and Conquests Of

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE Cornell University Library PA 3935.E5A3 1884 Anabasis of Alexander: or. The history o 3 1924 026 460 752 The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924026460752 THE ANABASIS OF ALEXANDER. THE ANABASIS OF ALEXANDER; OR, i^e Pislorg of tl^e ffiars anir Cottqnjcsts of '^hxmhtx tl^t (irtat. LITERALLY TRANSLATED, WITH A COMMENTARY, FROM THE GREEK OF ARRIAN THE NICOMEDIAN, BY E. J. CHINNOCK, M.A., LL.B., L0ND9N, Rector of Dumfries Academy. HODDER AND STOUGHTON, 27, PATERNOSTER ROW. MDCCCLXXXIV. "g 5~ /\ . 5"b r. f ^5- A3 Butler & Tanner. The Selwood Fiintiug Works, Frome, and London. PREFACE. When I began this Translation^ more than two years ago, I had no intention of publishing it; but as the work progressed, it occurred to me that Arrian is an Author deserving of more attention from the English- speaking races than he has yet received. No edition of his works has, so far as I am aware, ever appeared in England, though on the Continent many have been pub- lished. In the following Translation I have tried to give as literal a rendering of the Greek text as I could with- out transgressing the idioms of our own language. My theory of the duty of a Translator is, to give the ipsissima verba of his Author as nearly as possible, and not put into his mouth words which he never used, under the mistaken notion of improving his diction or his way of stating his case.