Finally Alone Together

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rebuilding the Ancestral Temple and Hosting Daluo Heaven and Earth Prayer and Enlightenment Ceremony

Cultural and Religious Studies, July 2020, Vol. 8, No. 7, 386-402 doi: 10.17265/2328-2177/2020.07.002 D DAVID PUBLISHING Rebuilding the Ancestral Temple and Hosting Daluo Heaven and Earth Prayer and Enlightenment Ceremony Wu Hui-Chiao Ming Chuan University, Taiwan Kuo, Yeh-Tzu founded Taiwan’s Sung Shan Tsu Huei Temple in 1970. She organized more than 200 worshipers as a group named “Taiwan Tsu Huei Temple Queen Mother of the West Delegation to China to Worship at the Ancestral Temples” in 1990. At that time, the temple building of the Queen Mother Palace in Huishan of Gansu Province was in disrepair, and Temple Master Kuo, Yeh-Tzu made a vow to rebuild it. Rebuilding the ancestral temple began in 1992 and was completed in 1994. It was the first case of a Taiwan temple financing the rebuilding of a far-away Queen Mother Palace with its own donations. In addition, Sung Shan Tsu Huei Temple celebrated its 45th anniversary and hosted Yiwei Yuanheng Lizhen Daluo Tiandi Qingjiao (Momentous and Fortuitous Heaven and Earth Prayer Ceremony) in 2015. This is the most important and the grandest blessing ceremony of Taoism, a rare event for Taoism locally and abroad during this century. Those sacred rituals were replete with unprecedented grand wishes to propagate the belief in Queen Mother of the West. Stopping at nothing, Queen Mother’s love never ceases. Keywords: Sung Shan Tsu Huei Temple, Temple Master Kuo, Yeh-Tzu, Golden Mother of the Jade Pond, Daluo Tiandi Qingjiao (Daluo Heaven and Earth Prayer Ceremony) Introduction The main god, Golden Mother of the Jade Pond (Golden Mother), enshrined in Sung Shan Tsu Huei Temple, is the same as the Queen Mother of the West, the highest goddess of Taoism. -

Yu-Huang -- the Jade Emperor

יו הואנג يو هوانج https://www.scribd.com/doc/55142742/16-Daily-Terms ヒスイ天使 Yu-huang -- The Jade Emperor Yu-huang is the great High God of the Taoists -- the Jade Emperor. He rules Heaven as the Emperor doe Earth. All other gods must report to him. His chief function is to distribute justice, which he does through the court system of Hell where evil deeds and thoughts are punished. Yu- huang is the Lord of the living and the dead and of all the Buddhas, all the gods, all the spectres and all the demons. According to legend he was the son of an emperor Ch'ing-te and his wife Pao Yueh-kuang who from his birth exhibited great compassion. When he had been a few years on the throne he abdicated and retired as a hermit spending his time dispensing medicine and knowledge of the Taoist texts. Some scholars see in this a myth of the sacred union of the sun and the moon, their son being the ruler of all Nature. "The good who fulfill the doctrine of love, and who nourish Yu-huang with incense, flowers, candles and fruit; who praise his holy name with respect and propriety -- such people will receive thirty kinds of very wonderful rewards." --Folkways in China L Holdus. http://www.chebucto.ns.ca/Philosophy/Taichi/gods.html Jade Emperor The Jade Emperor (Chinese: 玉皇; pinyin: Yù Huáng of the few myths in which the Jade Emperor really shows or 玉帝, Yù Dì) in Chinese culture, traditional religions his might. and myth is one of the representations of the first god (太 In the beginning of time, the earth was a very difficult 帝 tài dì). -

Appendix 2 Chinese Deities and Spirits

Appendix 2 Chinese deities and spirits This appendix includes a selection of the most common and important gods, goddesses, Buddhas, bodhisattvas, ancestors, and spirits that one can find in reli- gious sites across China. For each major religion, I present the most important deities of the pantheon as people would encounter them in a temple or other sacred space. Of course, there are many other deities presented in temples across China; yet, these are some of the most common of the range of deities – which ultimately cover all aspects of people’s physical and spiritual lives. Animistic ideas (referring to the idea of having or expecting mutually recip- rocal relationships of respect, gift-exchange, and communication; see Harvey 2013) in China stem at least as far back as the proto-Daoist text, the Zhua¯ngzi 庄子, from around 300 BCE, the first seven, inner chapters of which scholars think were written by Zhua¯ ng Zho¯u 庄周 (c. 369 BCE – c. 286 BCE). This text explains ideas about carefree living, naturalness, and relativity of perceptions, and Zhua¯ ngzi seems to attempt to get people to recognize that they live in a multi- species symbiotic community in which each aspect is in relationship and that each deserves respect. The Zhua¯ ngzi continues to be a widely-read and influential book among contemporary Chinese readers. Other popular literary texts include religiously-informed animistic ideas as well. Journey to the West (Xı¯yóujì 西游记), The Investiture of the Gods (Fe¯ngshén Yaˇnyì 封神演义), Dream of the Red Chamber (Hónglóu mèng 红楼梦), and the Water Margin (Shuıˇ huˇ zhuàn 水浒传; aka., Outlaws of the Marsh), all contain examples of some natural phenomenon such as a rock, animal, or flower, which has absorbed the essence of the cosmos for so long that it becomes a spirit being and chooses to incarnate in the human world to experience life in a human form. -

Working Papers

Working Papers www.mmg.mpg.de/workingpapers MMG Working Paper 17-08 ● ISSN 2192-2357 FABIAN GRAHAM Visual anthropology: a temple anniversary in Singapore Religious and Ethnic Diversity und multiethnischer Gesellschaften Max Planck Institute for the Study of Max Planck Institute for the Study of Max-Planck-Institut zur Erforschung multireligiöser Fabian Graham Visual anthropology: a temple anniversary in Singapore MMG Working Paper 17-08 Max-Planck-Institut zur Erforschung multireligiöser und multiethnischer Gesellschaften, Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity Göttingen © 2017 by the author ISSN 2192-2357 (MMG Working Papers Print) Working Papers are the work of staff members as well as visitors to the Institute’s events. The analyses and opinions presented in the papers do not reflect those of the Institute but are those of the author alone. Download: www.mmg.mpg.de/workingpapers MPI zur Erforschung multireligiöser und multiethnischer Gesellschaften MPI for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity, Göttingen Hermann-Föge-Weg 11, 37073 Göttingen, Germany Tel.: +49 (551) 4956 - 0 Fax: +49 (551) 4956 - 170 www.mmg.mpg.de [email protected] Abstract Based on the hypothesis that the inclusion of visual media provides insights into non-verbal communication not provided by the written word alone, this paper repre- sents an experimental approach to test the usefulness of reproducing fieldwork pho- tography in directing reader’s attentions to probe the emic understandings of deific efficacy, and the researcher’s selective bias which the images implicitly or explicitly portray. This paper therefore explores the use of the visual image to illustrate that a reader’s own analysis of proxemics and kinesics allows for a deeper understanding of emic perspectives by drawing insights from the manipulation of material objects and from non-verbal communication – insights that the written word may struggle to accurately portray. -

Handbook of Chinese Mythology TITLES in ABC-CLIO’S Handbooks of World Mythology

Handbook of Chinese Mythology TITLES IN ABC-CLIO’s Handbooks of World Mythology Handbook of Arab Mythology, Hasan El-Shamy Handbook of Celtic Mythology, Joseph Falaky Nagy Handbook of Classical Mythology, William Hansen Handbook of Egyptian Mythology, Geraldine Pinch Handbook of Hindu Mythology, George Williams Handbook of Inca Mythology, Catherine Allen Handbook of Japanese Mythology, Michael Ashkenazi Handbook of Native American Mythology, Dawn Bastian and Judy Mitchell Handbook of Norse Mythology, John Lindow Handbook of Polynesian Mythology, Robert D. Craig HANDBOOKS OF WORLD MYTHOLOGY Handbook of Chinese Mythology Lihui Yang and Deming An, with Jessica Anderson Turner Santa Barbara, California • Denver, Colorado • Oxford, England Copyright © 2005 by Lihui Yang and Deming An All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Yang, Lihui. Handbook of Chinese mythology / Lihui Yang and Deming An, with Jessica Anderson Turner. p. cm. — (World mythology) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-57607-806-X (hardcover : alk. paper) — ISBN 1-57607-807-8 (eBook) 1. Mythology, Chinese—Handbooks, Manuals, etc. I. An, Deming. II. Title. III. Series. BL1825.Y355 2005 299.5’1113—dc22 2005013851 This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook. Visit abc-clio.com for details. ABC-CLIO, Inc. 130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911 Santa Barbara, California 93116–1911 This book is printed on acid-free paper. -

An Alternative Study of Chinese History: Two Daoist Temples

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2008 An alternative study of Chinese history: Two Daoist temples Joan Lorraine Mann University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Mann, Joan Lorraine, "An alternative study of Chinese history: Two Daoist temples" (2008). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 2304. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/ryst-56ao This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN ALTERNATIVE STUDY OF CHINESE HISTORY: TWO DAOIST TEMPLES by Joan Lorraine Mann Bachelor of Arts San Jose State University 1979 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Master of Arts Degree in History Department of History College of Liberal Arts Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas May 2008 UMI Number: 1456353 Copyright 2008 by Mann, Joan Lorraine All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. -

Jade Myths and the Formation of Chinese Identity

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, April 2017, Vol. 7, No. 4, 377-398 doi: 10.17265/2159-5836/2017.04.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING Jade Myths and the Formation of Chinese Identity YE Shu-xian LIU Wan-er Shanghai Jiaotong University, Shanghai, China Beijing Institute of Technology, Beijing, China Reality is constructed by societies, whose process must be analyzed by the sociology of knowledge. The “reality”, taken as granted by the public, has sharp contrast from one society to another. By Peter Berger and Thomas Luckman: The Social Construction of Reality Chinese civilization is the only surviving one that has a continual history that lasts for several thousand years since the Stone Age. What’s the secret of its lasting cultural vitality? How can it live through numerous military conflicts and political transitions and still firmly hold a large population of various ethnics within its administration? A long-established cultural centripetal force, i.e. cultural identity shared by multi parties, shall be the key to former questions. According to current focus of cultural research, this force is termed as “Chinese identity”, which explores the formation and continuation of Chinese civilization from the perspective of cultural identity. What is cultural identity? A simplified answer is: Cultural identity fundamentally refers to ethnicity. This characterizes a group whose members claim a common history or origin and a specific cultural heritage, no matter that the history or origin is often mythicized or that the cultural legacy is never totally homogeneous. The essential thing is that these common elements are lived by the concerned group as distinctive characteristics and perceived as such by others1. -

Commonlit | the Four Dragons

Name: Class: The Four Dragons In this folktale, four dragons work to help a community that is suffering from a long drought. As you read, take notes on what the dragons do to help the people. [1] Once upon a time, there were no rivers and lakes on earth, but only the Eastern Sea, in which lived four dragons: the Long Dragon, the Yellow Dragon, the Black Dragon, and the Pearl Dragon. One day the four dragons flew from the sea into the sky. They soared and dived, playing at hide- and-seek in the clouds. “Come over here quickly!” the Pearl Dragon cried out suddenly. “What’s up?” asked the other three, looking down in the direction where the Pearl Dragon pointed. On the earth they saw many people putting out "Untitled" by Rhonlee is licensed under CC0 fruits and cakes, and burning incense sticks. They were praying! A white-haired woman, kneeling on the ground with a thin boy on her back, murmured, [5] “Please send rain quickly, God of Heaven, to give our children rice to eat.” For there had been no rain for a long time. The crops withered, the grass turned yellow and fields cracked under the scorching sun. “How poor the people are!” said the Yellow Dragon. “And they will die if it doesn’t rain soon.” The Long Dragon nodded. Then he suggested, “Let’s go and beg the Jade Emperor for rain.” So saying, he leapt into the clouds. The others followed closely and flew towards the Heavenly Palace. Being in charge of all the affairs in heaven, on earth, and in the sea, the Jade Emperor was very powerful. -

Chinese Zodiac

Name: edHelper Chinese Fable: Chinese Zodiac Long ago in China, the Jade Emperor, the almighty Chinese God, decided to have a race. The Jade Emperor was the ruler of the heavens. He announced that he would set up a system that runs in a 12-year cycle. He called it the Zodiac. He offered to hold a contest on his birthday. The first twelve animals of his kingdom to arrive at the finish line would receive the honor of having a year named after them. All the animals were very excited! Rat was ambitious. It wanted to win the first prize. Yet, it had two problems. The first was about the timing. Because the race would start at the crack of dawn, Rat was afraid that it could not wake up on time. The second was about the route. As the finish line would be directly beyond a swift river, Rat needed to find a way to cross the current. Just when Rat was contemplating a solution, it bumped into its best friend, Cat. After a lengthy discussion, the two animals came up with a brilliant idea. They decided to solicit help from Ox. Rat and Cat figured that Ox - always being an early riser and a good swimmer - could wake them up before sunrise and carry them across the river. With their minds made up, Rat and Cat went to see Ox. Out of kindness, Ox agreed to help. Hence, the three animals formed an alliance. They promised to help each other, so they could share the first prize. -

The Chinese New Year

The Chinese New Year The Chinese Zodiac The Chinese calendar is a lunisolar calendar; thus, new year day is usually in late January or early February, and it is on a day with a new moon (ie: no moon). For 2021, Chinese New Year is on 12 February - Year of the Ox. No one knows when the Chinese calendar officially began, but it is generally accepted that Year One corresponds to the time when Emperor Huang Di began ruling China (equivalent to 2697 BC). Thus, 2020 (after Jan 25) corresponds to the Chinese year 4718. In Chinese astrology, the zodiac is represented by a 12-year cycle of 12 animals – these are the Rat, Ox, Snake, Horse, Rabbit, Tiger, Dragon, Monkey, Rooster, Dog, Pig, and the Sheep. Of all the animals in the world, why were these 12 chosen? There are many stories explaining this and they all share a similar theme: there was a race and the first 12 animals who arrived at the finish line were chosen. Rat is small but he is clever. He convinces Ox to give him a ride, but just as Ox approaches the finish line, Rat jumps ahead of Ox making Rat first on the list and Ox second. The Great Race There exists a story, in Chinese mythology, of a great race that decided which animals made it into the Zodiac and in what order. The Jade Emperor, the ruler of all gods within Chinese mythology, hosted the race. To finish the race and become one of 12 animals in the calendar, the animals had to cross a river. -

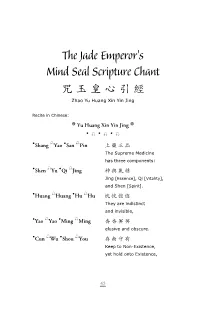

The Jade Emperor's Mind Seal Scripture Chant

The Jade Emperor’s Mind Seal Scripture Chant Zhao Yu Huang Xin Yin Jing Recite in Chinese: ! Yu Huang Xin Yin Jing ! • " • " • " •Shang "Yao •San "Pin The Supreme Medicine has three components: •Shen "Yu •Qi "Jing Jing [Essence], Qi [Vitality], and Shen [Spirit]. •Huang "Huang •Hu "Hu They are indistinct and invisible, •Yao "Yao •Ming "Ming elusive and obscure. •Cun "Wu •Shou "You , Keep to Non-Existence, yet hold onto Existence, 45 Taoist Chanting & Recitation •Qing "Ke •Er "Cheng 小 and perfection is yours in an instant. •Jiong "Feng •Hun "He When distant winds blend together, •Bai "Ri •Gong "Ling in one hundred days of spiritual work •Mo "Zhao •Shang "Di and morning recitation to the Shang Di, •Yi "Ji •Fei "Sheng then in one year you will soar as an immortal. •Zhi "Zhe •Yi "Wu For those who know, awakening is easy. •Mei "Zhe •Nan "Xing For those who are ignorant, the practices are difficult. •Lu "Jian •Tian "Guang Fulfilling vows illuminates the Heavens. •Hu "Xi •Yu "Qing Breathing nourishes youthfulness. 46 The Jade Emperor’s Mind Seal Scripture Chant •Chu "Xuan •Ru "Pin 美 Depart from the mysterious and enter the female. •Ruo "Wang •Ruo "Cun Appears to have perished, yet appears to exist, •Mian "Mian •Bu "Jue ) the Tao is continuous and unbroken, •Gu "Di •Shen "Gen like a firm stem with deep roots. •Ren "Ge •You "Jing , Each person has Jing. •Jing "He •Qi "Shen The Shen unites with the Jing. •Shen "Yu •Qi "He The Shen unites with the Qi. •Qi "He •Ti "Zhen Then the True Body unites with the Qi. -

1 Unit 2 Topic 2 Deities in Chinese Myths and Legends

© 2021 Cengage Learning Asia Pte Ltd UNIT 2 TOPIC 2 DEITIES IN CHINESE MYTHS AND LEGENDS __________________________________________________________________________ Pre-knowledge Before class, students should read Unit 2 Topic 2 and discuss some general questions related to Chinese myths, legends and gods. They may draw on their own experience. Aim and Objectives Topic 2 aims to provide students with some knowledge of Chinese myths, legends and gods. It will also equip them with some knowledge of the significance of these myths, legends and gods to the Chinese society. One such legend they will learn about is the dragon. Teaching and Learning Activities Activity 1 Show your students the image of a poster featuring the Kitchen God below. Have a class discussion on what is presented in the poster. Edward Theodore Chalmers Werner, commons.wikimedia.org Activity 2 Have your students visit the website http://chineseculture.about.com. Show them two different fables, one Chinese and one Western. Have them work in groups of five to compare the similarities and differences between the two fables. Each group will then present their findings to the class. You may share these stories with your class: 1. Cheap Tricks Never Last – The Donkey of Guizhou (黔驴技穷) 1 © 2021 Cengage Learning Asia Pte Ltd • Thousands of years ago, donkeys were not found in Guizhou Province. Meddlers shipped one into this area. • One day, a tiger was looking for his prey when he saw the huge strange animal which frightened him. He studied the donkey from behind some bushes and approached it to have a closer look when it seemed like he was harmless.