The Fundamental Theorem of Kendo? December 17, 2011 Article (Part Of) Retrieved From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Realm of the Spirit

The Power of Harmony In The Realm of the Spirit Quantum Aikido, Creativity and The Unified field R. Moon © 2001 Zanshin Press 1 In the Realm of the Spirit Zanshin Press 75 Los Piños Nicasio, CA 94946 zanshinryu.com extraordinarylistening.com aikidoofmarin.com quantumedge.org © Copyright 2001 Zanshin Press All rights reserved Zanshin Press Zanshin Press - 2 -- In the Realm of the Spirit Acknowledgments To those who have gone before My teacher Robert Nadeau and his teacher Morihei Ueshiba O Sensei and his teacher the Aiki Kami For all they have to given me and those who follow Zanshin Press - 3 -- In the Realm of the Spirit Table of Contents Preface The Art of Aikido An Introduction The Principles The Principle of Energy The Principle of Centering The Principle of Grounding The Principle of Entering The Principle of Harmony The Principle of Unification The Principle of Resonance The Study & Practice Zanshin Press - 4 -- In the Realm of the Spirit Preface: On Learning The process of learning requires entering the unknown. Otherwise we gain only additive knowledge that doesn't disturb our present descriptions or change our existing order. In the Realm of the Spirit looks at our relationship to life through the art of Aikido. By looking through different windows of a house, we can come to know more about the inhabitants. What I describe is a view through one of many windows. My view is just a view. This is how it looks to me at this moment. Aikido is a profound art. This simplified description represents a doorway to learning, not the art. -

School of Traditional Martial Arts

School of Traditional Martial Arts ANCIENT THEORY, MODERN PRACTICE Kenshinryu — 3-5 Briggs St Palmwoods Qld — Ph:(6107) 5457 3716 – www.kenshin.com.au Contents LETTER FROM THE HEAD TEACHER ........................................................................................................ 1 KENSHINRYU.................................................................................................................................................. 2 DOJO PHILOSOPHY ....................................................................................................................................... 4 AIKIDO HISTORY ........................................................................................................................................... 5 SHINTO MUSO RYU HISTORY..................................................................................................................... 6 AIKIDO CLASSES ........................................................................................................................................... 7 SHINTO MUSO RYU CLASSES ..................................................................................................................... 7 JUNIOR AIKIDO .............................................................................................................................................. 7 DOJO ETIQUETTE........................................................................................................................................... 8 PRECAUTIONS FOR TRAINING .................................................................................................................. -

Zanshin Jan 2005.Pub

Volume 8 Issue 1 Newsletter of the Yoshukan Karate Association February 2005 Yoshukan Honbu Dojo Opened! Yoshukan Honbu Dojo Opened The Yoshukan Karate Association Honbu (Headquarters) Dojo opened in Mississauga, Ontario on January 1st, 2005. The dojo has 3,600 Sq. Ft. of floor space and houses: Main dojo floor (1,500 sq. ft.); second floor matted dojo; office; locker rooms; handicapped washroom; full kitchen; parent and stu- dent lounge; exercise area with universal gym; treadmill; stretching bar; library; washer/dryer units; and (under con- struction) massage/meditation room and sauna. The dojo project was lead by Sensei Betty Gormley and Gen- eral Contractor, Gordon Deane. The building is owned by Kancho Robertson and Sensei Gormley who took possession New Honbu Dojo main floor. A Kumite ring has been added in in August, 2004. Gord’s work crew (Spud; Matt; Keith; Jeff) red hardwood for members to practice their competition skills and the dojo volunteers (dozens!!) pitched in to make the space something we are all proud of. Special thanks to the dozens of dojo volunteers who devoted their XMAS-New Year’s break to get the dojo up and run- ning for our January 1st launch. Dojo members also generously donated the fridge; stove; dishwasher; microwave; coffee maker and kettle. Academy parents now get to have a coffee and read the paper while their kids train. The main dojo floor was constructed with special rubber ‘pucks’ (placed one foot apart) to give the floor a special ‘bounce’ while training. The locker rooms feature separate washrooms, showers, sinks, cubbies and (shortly) lockers. -

Japanese Terms.Indd

Norwalk CommonKendo Dojo Japanese terms used during practice Southeast Japanese Community Center 14615 Gridley Road. Norwalk, ShortCA 90650 Vowels Vowel Combinations [email protected] as in father,m alms ei=e+i sounded as in day e as in pen, red ai=a+i sounded as in alive i as in ink, machine ou=o+u sounded as in float o as in open, ocean au=a+u sounded as in out u as in true, cruel Japanese Words and Phrases English Translations Ohayo gozaimasu Good morning Konnichiwa Hello Konbanwa Good evening Sayonara Goodbye Oyasumi nasai Good night Arigato gozaimashita Thank you very much Onegai shimasu I'm requesting (to practice) Hai Yes Sensei Instructor/Teacher Yudansha Black-belt students Kenshi Kendo students Sempai Elders/Seniors Kouhai Younger/Lower juniors Ichi One Ni Two San Three Shi Four Go Five Roku Six Shichi Seven Hachi Eight Ku/Kyu Nine Ju Ten Kiai Showing your spirit and feeling through your voice Kamae Ready stance in Kendo Chakuza Sit on the floor Seiza Sit properly Mokusou Meditation Yame Stop Naore Return to original position Rei Bow Kiritsu Stand up Keiko Practice Kakari geiko Continuous attack practice Zanshin Mental and physical alertness, especially after completing an attack Norwalk Kendo Dojo Southeast Japanese Community Center 14615 Gridley Road. Norwalk, CA 90650 [email protected] Kendo Terms Japanese English Translations Ashi sabaki Footwork Dan Ranking system for advanced levels (1=lowest, 10=highest); equivalent to black belt in other martial arts Datotsu no kikai Chance of strike Ippon shoubu One point -

Valley Aikido Member's Guide

VALLEY AIKID MEMBERS GUIDE By: Julia Freedgood Design: Liz Greene Photography and concept: Special Thanks to Shannon Brishols, WHAT IS AIKIDO? RL Sarafon, Skip Chapman Sensei and the Greater Aikido Community Aikido is a traditional Japanese martial art practiced for self development and defense. The word Aikido means “the way of harmony with ki.” Ki is hard to translate, but can be understood as breath power, spirit or universal life force. Morihei Ueshiba, or O-Sensei (great teacher) created Aikido in the early 1940s. A master of several classical Japanese martial arts (budo) including judo, kendo and jujitsu, O-Sensei developed Aikido to respond to the modern world. According to his son, Kisshomaru Ueshiba, Aikido is orthodox because it inherits the spiritual and martial tradition of ancient Japan . But O-Sensei Copyright VA © 2007 concluded that the true spirit of budo cannot be found in a All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system competitive atmosphere where brute force dominates and the or transmitted in any form by any process – photocopying, e-mail, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise – without the written permission of Valley Aikido. goal is victory at any cost. Instead, the path of Aikido leads to “victory over self” and is realized in the quest for self perfection of body, mind and spirit. Thus, unlike martial sports, Aikido avoids competition and VALLEY AIKIDO does not allow tournaments. Instead, it stresses collaborative practice allowing all students to pursue their individual Valley Aikido was founded by Paul Sylvain, shihan in 1985 to potential in an atmosphere of shared knowledge. -

Kyokushin Terminology

Kyokushin Terminology General Vocabulary General Japanese Greetings & Hai Yes Expressions Iee No Ohayô gozaimasu Good morning Watashi Me / I Konnichiwa Hello/Good afternoon Anata You Konbanwa Good evening Kare Him Arigatô gozaimasu Thank you! Doko Where Hajimemashite How do you do? Nan What Douzo yoroshiku Nice to meet you! Dare Who Dewa mata See you later Doshite Why Mata ashita See you tomorrow Itsu When Ja mata See ya! (less formal) Do/Ikaga How Sayonara Goodbye Ikura How many Shitsurei shimasu I'm leaving (very formal) Titles and Status Sumimasen Excuse me Dômo Thanks! Sosai President Onegaishimasu Please Kancho Director Dômo arigatou gozaimashita Hanshi Honorable Master Thank you very much (very polite) Shihan Grand Master (5th dan or more) Sensei School Master / Teacher (3rd dan or more) Sempai Senior / Teacher's assistant Shidoin Instructor Karateka Student Kohai Junior student Otagai Each other / Other students Yudansha Black belt student KyokushinGreetings Terminology and Salutes Osu Patience and Determination. Comes from 'oshi shinobu' which means to never give up. It also comes from 'osu no seishin' which means perseverance under pressure. It is used among kyokushin practionners to show respect or to say "I understand". Shinzen ni rei Greeting to the ancestors Shomen ni rei Greeting in direction of the person standing in the place of honor (usually more elevated than the students) Mokuso Meditation (silent thought) / Close your eyes Mokuso yame Open your eyes Shihan ni rei Greeting to the Shihan Sensei ni rei Greeting to the -

Applying Kendo No Kata in Shinai Kendo S

Applying Kendo no Kata in Shinai Kendo S. Quinlan January 5, 2020 This article assumes familiarity with the It can be difficult, especially for beginners, to parse the information from kendo no kata as well as several Japanese the kata and apply it to shinai kendo as this requires a firm grasp of several terms related to the kendo no kata and shinai kendo. All of this is in the descrip- complicated concepts, the understanding of which depends heavily on tions and glossary of the “Nihon Kendo experience, such as seme, tame, the san sappo, and the mitsu no sen. While no Kata & Kihon Bokuto Waza - Study Guide”, found here. at the same time the waza, footwork, kamae, and even the zanshin used in the kata themselves can seem completely disconnected from what is done in shinai kendo. This often relegates kata to something kendoka have tolearn “just for grading”. While there will be overlap between kata, the following were chosen as examples to be the simplest way in which the applications can be seen. PRinciples of the Kendo no Kata Applied to VaRious Shinai Kendo Situations Tachi Kata Kodachi Kata Application 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 Beginner kendo ✔ Key aspects of zanshin ✔ ✔ ✔ Applying basic seme ✔ Seme–tame ✔ Dealing with aggressive opponents ✔ ✔ Dealing with defensive opponents ✔ ✔ Fighting against jodan ✔ ✔ ✔ Effective oji waza ✔ Resisting seme ✔ Application Notes Beginner kendo Tachi kata #1 teaches sen, seme, correct maai, sutemi, zanshin. Both uchidachi and shi- dachi initially approach one another with a sense of spiritually building their intent to strike. -

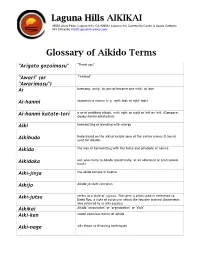

AIKIKAI Laguna Hills Glossary of Aikido Terms

Laguna Hills AIKIKAI 25555 Alicia Pkwy, Laguna Hills, CA 92653 | Laguna Hills Community Center & Sports Complex 949.295.6355 [email protected] Glossary of Aikido Terms "Arigato gozaimasu" "Thank you" "Awari" (or "finished" "Awarimasu") Ai harmony, unity, to join or become one with, to love Ai-hanmi asymmetric stance (e.g. right foot to right foot) a wrist grabbing attack, with right on right or left on left. (Compare: Ai-hanmi katate-tori Gyaku-hanmi katatedori) Aiki harmonizing or blending with energy budo based on the aiki principle (one of the earlier names O-Sensei Aikibudo used for Aikido) Aikido the way of harmonizing with the force and principle of nature one who trains in Aikido (specifically, at an advanced or professional Aikidoka level) Aiki-jinja the Akido temple in Iwama Aikijo Aikido jo-staff exercises refers to a style of jujutsu. The term is often used in reference to Aiki-jutsu Daito Ryu, a style of jujutsu in which the founder trained (Sometimes also referred to as aiki-jujutsu) Aikikai Aikido "association" or "organization" or "club" Aiki-ken sword exercises/forms of Aikido Aiki-nage aiki-throw (a throwing technique) Aiki-otoshi aiki drop (a throwing technique) Aiki-taiso aikido warm-up exercises Ashi leg or foot Atemi (also: Ate) strike Awase to blend/harmonize/match the timing of the attack and response leg movement using alternating steps, right and left (similar to a Ayumi-ashi normal walking gait) B Batto sword Batto-ho sword training Bo a longer wooden staff (approx. 180-200cm in length) Bokken wooden sword Bokuto wooden sword "Martial" or "military." The Kanji character for "bu" has two Bu components: one indicates a weapon, while the other means to stop or lay aside. -

Ryūshin Shōchi Ryū

RYŪSHIN SHŌCHI RYŪ A cura di Daniel Leclerc Traduzione dal francese di Patrizia Claut Vecchiet Aggiornato al 1/12/2014 IAI JUTSU I FONDAMENTALI (reishiki, kamae, tenkū no tachi) I WAZA REISHIKI Il Reishiki non è considerato fondamentale per la scuola. Ma ne proponiamo comunque le sequenze fotografiche : • di inizio e fine lezione, • di tō-rei in piedi. NB : Contrariamente a molti altri stili, il Ryū non fa differenza fra il saluto alla spada eD al kamiza cioè, in entrambi i casi, si appoggiano prima la mano sinistra e poi la destra quando ci si inchina. Nel momento di risalire la mano sinistra lascia il tatami per ultima. REISHIKI DI INIZIO LEZIONE Posizione di fronte al kamiza: corpo in shizen-tai, spada in sagetō. 1) All’ordine dell’assistente : « SEIZA », prendere la posizione indicata. 2) Appoggiare la spada davanti come mostrato, 3) portare la spada a destra del corpo,tsuba all’altezza del ginocchio, ha all’interno. 4) L'insegnante è rivolto al kamiza. All’ordine dell’assistente: « SHINZEN NI : REI ! », salutare. 5) L’insegnante si rivolge dunque allo shimoza e, agli ordini dell’assistente : « SENSEI NI : REI ! » e « OTAGAI NI : REI ! », ripetere il saluto. Infine tornare in seiza. A fine lezione, l’insegnante è subito rivolto al shimoza e la sequenza degli ordini diventa : « SENSEI NI : REI ! » (insegnante rivolto al shimoza) « SHINZEN NI : REI ! » (insegnante rivolto al kamiza) « OTAGAI NI : REI ! » (insegnante rivolto al shimoza) Infine, eseguire tō-rei di fine lezione. TŌ-REI DI INIZIO LEZIONE Senza distogliere il metsuke, prendere il sageo e la spada con la mano destra e portarli verticalmente davanti a sé con lo ha rivolto verso il corpo. -

Kihon Kata (Taikyoku Shodan)

Zanshin Kai Karate Do – Kata Series – Volume 01. Zanshin Kai Karate Do and Kobudo presents: KIHON KATA (TAIKYOKU SHODAN) Information, history, hints, tips, secrets – all revealed… by Gary Simpson 雅利 真風尊 © 2020 Gary Simpson & Zanshin Kai Karate Do & Kobudo 1 Zanshin Kai Karate Do – Kata Series – Volume 01. IMPORTANT DISCLAIMER NOTICE This manual is intended for educational purposes only. None of the material within these pages should be regarded as a substitute for ‘hands-on’ training. Every student of karate has different goals and expectations. This combined with vast differences in personality, knowledge, discipline, training, experience, understanding and ability means that every person will reach a different outcome. The information depicted within is the experience of the author over the many years of his karate journey. The material presented is offered in good faith and in the spirit of karate-do. There is no intention whatsoever to decry or criticize any other person, club, style. You are who you are. I am who I am. The author and publisher will not accept any responsibility for any errors or omissions. This material has been extensively checked. However, no responsibility whatsoever is accepted by the author for any material contained herein that may be inadvertently incorrect. To the best of his knowledge it is correct. Again, there is no intention by the author to disrespect any individual, style or organization with any of the material shared in this booklet. This booklet is about sharing knowledge and technique ONLY. Zanshin Kai Karate Do & Kobudo Published by: PO Box 396 Leederville Western Australia 6903 v 7.8-240520 © 2017, 2020 Gary Simpson & ZKKD. -

Grading Advice

British Aikido Federation Technical Director, Minoru Kanetsuka 7th Dan, Aikikai Foundation, Tokyo IMPORTANT ELEMENTS FOR GRADING 1. Knowledge of technique 5. Maai & Zanshin 2. Contact (Ki) 6. Ukemi 3. Posture 7. Spirit 4. Flow & Flexibility 8. Manner and Attitude Candidates for kyu grades, below Ikkyu, should complete BAF Form 1(Application for Kyu Grade Examination) and Form 2 (Grading Result Form) Candidates for Ikkyu and all Yudansha grades should complete Form 1A (part 1) (Application for Ikkyu / Yudansha Examination), Form 1A (part 2) (Instructors Comments) and Form 2 (Grading Result Form). 1. Knowledge of technique. The candidate should show full understanding of the techniques specifically required for the grade being taken, as prescribed by the grading syllabus. They should, however, also be prepared to demonstrate techniques and understanding outside the range of the grading syllabus if required (e.g. if particular emphasis has been made during a class at Summer School). It is advisable to study the contents of the Teaching Syllabus as well as the Grading Syllabus. Yudansha should have full knowledge of all aspects of Aikido relevant to their grade (e.g. multiple attacks, weapons, jiyuwaza, etc.) 2. Contact (Ki.) (also called Kokyu Ryoku) is the natural power that can be produced when body and consciousness (mind) are unified. In the higher state of Aikido, kokyu ryoku is understood as spiritual energy that transforms into physical energy. Certain techniques of breathing also stimulate this process of transformation, (kokyu: breath ryoku: power). In Aikido, training to cultivate or to discover this kokyu ryoku is especially important because its discovery is necessary for the realisation of the potential that every person has within his or her consciousness. -

GRADING REQUIREMENTS WHITE BELT (6Th Kyu)

RODNEY HOBSON KARATE ACADEMY - GRADING REQUIREMENTS WHITE BELT (6th kyu) TO YELLOW BELT (5th kyu) A minimum of 4 months of regular twice-a-week training is recommended to test for yellow belt. General Principles (Tsuruoka Federation “mandate”) • The student should have a clear understanding of the techniques on the test (e.g. elbow moves first on blocks, knees bent on set moves etc.). • No speed and no power (e.g. no hip rotation on blocks) is required. • Complete upper/lower body separation is acceptable (e.g. can step, pause, and then block). • A basic understanding of dojo etiquette, attitude, and formalities must be demonstrated. Kihon (basics) Stances: attention kiotsuke (musubi dachi) kneeling seiza natural stance shizen-tai horse stance kiba dachi front stance zenkutsu dachi Blocks: high block jodan age uke middle outside block chudan soto uke middle inside block chudan uchi uke low block gedan barai Punches: front punch tsuki (zuki) front lunge punch oi-tsuki reverse punch gyaku tsuki Kicks: front kick mae geri Movements: • Bow (rei) when standing and kneeling. • Walking forward and backward in front stance. • Turning (mawate) 90o and 180o in front stance • Be able to do all four blocks and high, middle, low punches from natural and horse-riding stance. • Be able to demonstrate lunge punch (high, middle, low) and high and low blocks while moving forward and backward in front stance. • Front kicking from natural and front stances. Kumite (sparring) The requirement at this level is that students must perform 3-point sparring (sanbon kumite) using high punch, middle punch, and low punch for attacks and reverse punch for a counter-attack.