Maria Vittoria Fontana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of Kufic Script in Islamic Calligraphy and Its Relevance To

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1999 A study of Kufic script in Islamic calligraphy and its relevance to Turkish graphic art using Latin fonts in the late twentieth century Enis Timuçin Tan University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Tan, Enis Timuçin, A study of Kufic crs ipt in Islamic calligraphy and its relevance to Turkish graphic art using Latin fonts in the late twentieth century, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 1999. http://ro.uow.edu.au/ theses/1749 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. A Study ofKufic script in Islamic calligraphy and its relevance to Turkish graphic art using Latin fonts in the late twentieth century. DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by ENiS TIMUgiN TAN, GRAD DIP, MCA FACULTY OF CREATIVE ARTS 1999 CERTIFICATION I certify that this work has not been submitted for a degree to any university or institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by any other person, expect where due reference has been made in the text. Enis Timucin Tan December 1999 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I acknowledge with appreciation Dr. Diana Wood Conroy, who acted not only as my supervisor, but was also a good friend to me. I acknowledge all staff of the Faculty of Creative Arts, specially Olena Cullen, Liz Jeneid and Associate Professor Stephen Ingham for the variety of help they have given to me. -

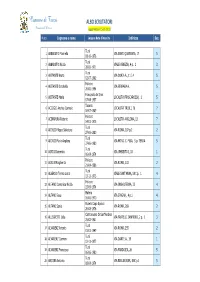

ALBO Degli SCRUTATORI

Comune di Tursi ALBO SCRUTATORI Provincia di Matera (aggiornato al 15‐01‐2019) N.ord. Cognome e nome Luogo e data di nascita Indirizzo Sez. Tursi 1 ABBADUTO Marinella VIA SANTI QUARANTA, 17 5 08-10-1976 Tursi 2 ABBADUTO Nicola VIALE VENEZIA, 4 p. 2 3 28-06-1971 Tursi 3 ABITANTE Bruna VIA DORIA A., 11 I.4 5 02-07-1962 Policoro 4 ABITANTE Donatella VIA FERRARA A. 5 20-06-1994 Francavilla In Sinni 5 ABITANTE Maria LOCALITA' FRASCAROSSA, 1 5 07-04-1957 Taranto 6 ACCOGLI Andrea Carmelo LOCALITA' TROJLI, 76 7 10-07-1989 Policoro 7 ACINAPURA Roberto LOCALITA' ANGLONA, 13 7 14-01-1975 Tursi 8 ADDUCI Filippo Salvatore VIA ROMA, 187 p.2 2 27-06-1980 Tursi 9 ADDUCI Maria Anglona VIA MONS. C. PUJA, 5 p. TERRA 5 27-06-1980 Tursi 10 AGATA Domenico VIA UMBERTO I, 10 1 06-04-1974 Policoro 11 AGATA Margherita VIA ROMA, 233 2 21-04-1986 Tursi 12 ALBERGO Teresa Lucia VIALE SANT'ANNA, SNC p. 1 4 13-12-1973 Policoro 13 ALFANO Domenico Nicola VIA INGHILTERRA, 23 4 15-09-1974 Matera 14 ALFANO Rosa VIA SPAGNA, 4 p.1 4 16-06-1970 Roseto Capo Spulico 15 ALFANO Sonia VIA ROMA, 269 2 20-08-1976 Castronuovo Di Sant'Andrea 16 ALLEGRETTI Lidia VIA FRATELLI ZANFRINO, 2 p. 1 3 25-02-1961 Tursi 17 ALVARENZ Antonio VIA ROMA, 235 2 01-01-1949 Tursi 18 ALVARENZ Carmen VIA DANTE A., 19 1 12-11-1977 Tursi 19 ALVARENZ Francesca VIA PANDOSIA, 26 5 06-06-1980 Tursi 20 ANCORA Antonio VIA BERLINGUER, SNC p.1 5 08-04-1974 Comune di Tursi ALBO SCRUTATORI Provincia di Matera (aggiornato al 15‐01‐2019) N.ord. -

Medici Convenzionati Con La ASM Elencati Per Ambiti Di Scelta

DIPARTIMENTO CURE PRIMARIE S.S. Organizzazione Assistenza Primaria MMG, PLS, CA Medici Convenzionati con la ASM Elencati per Ambiti di Scelta Ambito : Accettura - Aliano - Cirigliano - Gorgoglione - San Mauro Forte - Stigliano 80 DEFINA/DOMENICA Accettura VIA IV NOVEMBRE 63 bis 63 bis 9930 SARUBBI/ANTONELLA STIGLIANO Corso Vittorio Emanuele II 45 308 SANTOMASSIMO/LUIGINA MIRIAM Aliano VIA DELLA VITTORIA 4 8794 MORMANDO/ANTONIO Cirigliano VIA FONTANA 8 8794 MORMANDO/ANTONIO Gorgoglione via DE Gasperi 30 3 BELMONTE/ROCCO San Mauro Forte VIA FRATELLI CATALANO 5 4374 MANDILE/FRANCESCO San Mauro Forte CORSO UMBERTO I 14 4242 CASTRONUOVO/ANTONIO Stigliano CORSO UMBERTO 57 8474 DIGILIO/MARGHERITA CARMELA Stigliano Corso Umberto I° 29 9382 DIRUGGIERO/MARGHERITA Stigliano Via Zanardelli 58 Ambito : Bernalda 9292 CALBI/MARISA Bernalda VIALE EUROPA - METAPONTO 10 9114 CARELLA/GIOVANNA Bernalda VIA DEL CONCILIO VATICANO II 35 8523 CLEMENTELLI/GREGORIO Bernalda CORSO UMBERTO 113 7468 GRIECO/ANGELA MARIA Bernalda VIALE BERLINGUER 15 7708 MATERI/ANNA MARIA Bernalda PIAZZA PLEBISCITO 4 9283 PADULA/PIETRO SALVATORE Bernalda VIA MONTESCAGLIOSO 28 9698 QUINTO/FRANCESCA IMMACOLATA Bernalda Via Nuova Camarda 24 4366 TATARANNO/RAFFAELE Bernalda CORSO UMBERTO 113 327 TOMASELLI/ISABELLA Bernalda CORSO UMBERTO 113 9918 VACCARO/ALMERINDO Bernalda CORSO UMBERTO 113 8659 VITTI/MARIA ANTONIETTA Bernalda VIA TRIESTE 14 Ambito : Calciano - Garaguso - Oliveto Lucano - Tricarico MEDICO INCARICATO Calciano DISTRETTO DI CALCIANO S.N.C. MEDICO INCARICATO Oliveto Lucano -

Palermo Guide

how to print and assembling assembleguide the the guide f Starting with the printer set-up: Fold the sheet exactly in the select A4 format centre, along an imaginary line, and change keeping the printed side to the the direction of the paper f outside, from vertical to horizontal. repeat this operation for all pages. We can start to Now you will have a mountain of print your guide, ☺ flapping sheets in front of you, in the new and fast pdf format do not worry, we are almost PDF there, the only thing left to do, is to re-bind the whole guide by the edges of the longest sides of the sheets, with a normal Now you will have stapler (1) or, for a more printed the whole document aesthetic result, referring the work to a bookbinder asking for spiral binding(2). Congratulations, you are now Suggestions “EXPERT PUBLISHERS”. When folding the sheet, we would suggest placing pressure with your fingers on the side to be folded, so that it might open up, but if you want to permanently remedy this problem, 1 2 it is enough to apply a very small amount of glue. THE PALERMO CITY GUIDE © Netplan - Internet solutions for tourism © Netplan - Internet solutions for tourism © 2005 Netplan srl. All rights reserved. © Netplan - Internet solutions for tourism All material on this document is © Netplan. THE PALERMO CITY GUIDE 1 Summary THINGS TO KNOW 3 History and culture THINGS TO SEE 4 Churches and Museums 6 Historical buildings and monuments 8 Places and charm THINGS TO TRY 10 Food and drink 11 Shopping 12 Hotels and lodgings THINGS TO EXPERIENCE 13 Events 14 La Dolce Vita ITINERARIES 15 A special day 16 Trip outside the city 32 © Netplan - Internet solutions for tourism THE PALERMO CITY GUIDE / THINGS TO KNOW 3 4 THE PALERMO CITY GUIDE / THINGS TO SEE History and culture Churches and Museums population spread out throughout the island. -

The Qur'anic Manuscripts

The Qur'anic Manuscripts Introduction 1. The Qur'anic Script & Palaeography On The Origins Of The Kufic Script 1. Introduction 2. The Origins Of The Kufic Script 3. Martin Lings & Yasin Safadi On The Kufic Script 4. Kufic Qur'anic Manuscripts From First & Second Centuries Of Hijra 5. Kufic Inscriptions From 1st Century Of Hijra 6. Dated Manuscripts & Dating Of The Manuscripts: The Difference 7. Conclusions 8. References & Notes The Dotting Of A Script And The Dating Of An Era: The Strange Neglect Of PERF 558 Radiocarbon (Carbon-14) Dating And The Qur'anic Manuscripts 1. Introduction 2. Principles And Practice 3. Carbon-14 Dating Of Qur'anic Manuscripts 4. Conclusions 5. References & Notes From Alphonse Mingana To Christoph Luxenberg: Arabic Script & The Alleged Syriac Origins Of The Qur'an 1. Introduction 2. Origins Of The Arabic Script 3. Diacritical & Vowel Marks In Arabic From Syriac? 4. The Cover Story 5. Now The Evidence! 6. Syriac In The Early Islamic Centuries 7. Conclusions 8. Acknowledgements 9. References & Notes Dated Texts Containing The Qur’an From 1-100 AH / 622-719 CE 1. Introduction 2. List Of Dated Qur’anic Texts From 1-100 AH / 622-719 CE 3. Codification Of The Qur’an - Early Or Late? 4. Conclusions 5. References 2. Examples Of The Qur'anic Manuscripts THE ‘UTHMANIC MANUSCRIPTS 1. The Tashkent Manuscript 2. The Al-Hussein Mosque Manuscript FIRST CENTURY HIJRA 1. Surah al-‘Imran. Verses number : End Of Verse 45 To 54 And Part Of 55. 2. A Qur'anic Manuscript From 1st Century Hijra: Part Of Surah al-Sajda And Surah al-Ahzab 3. -

Ibn Hamdis." 26-27: Cormo

NOTE TO USERS The original manuscript received by UMI contains pages with slanted print. Pages were microfilmed as received. This reproduction is the best copy available Medieval Sicilian fyric poetry: Poets at the courts of Roger IT and Frederick II Karla Mdette A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of PhD Graduate Department of Medieval Studies University of Toronto O Copyright by Karla Mdlette 1998 National Library BibIioth&que nationale me1 of-& du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, nre Wellington OttawaON K1AW OttawaON K1AON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde me licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distri'bute or sell reproduire, prtter, distnbuer cu copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de nlicrofiche/film, de reprod~ctior~sur papier ou sur format eectronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriete du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protege cette these. thesis nor substantial extracts from it Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celleci ne doivent Stre imprimes reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Medieval Sicilian Lyric Poetry: Poets at the Courts of Roger lI and Frederick II Submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of PhD, 1998 Karla Mallette Centre for Medieval Studies, University of Toronto During the twelfth century, a group of poets at the Norman court in Sicily composed traditional Arabic panegyrics in praise of the kingdom's Christian monarchs. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Infonnadon Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 A CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF CONTEMPOEU^.RY IRAQI ART USING SIX CASE STUDIES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Mohammed Al-Sadoun ***** The Ohio Sate University 1999 Dissertation Committee Approved by Dr. -

University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan ARABIC CALLIGRAPHY in CONTEMPORARY EGYPTIAN

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 66-6296 SIDA, Youssef Mohamed Ali, 1922- ARABIC CALLIGRAPHY IN CONTEMPORARY EGYPTIAN MURALS, WITH AN ESSAY ON ARAB TRADITION AND ART. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1965 Fine Arts University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan ARABIC CALLIGRAPHY IN CONTEMPORARY EGYPTIAN MURALS .WITH AN ESSAY ON ARAB TRADITION AND ART DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Youssef Mohamed Ali Sida, M. Ed. 4c * * * * * The Ohio State University 1965 / Approved by ) Adviser School of Fine and Applied Arts ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to acknowledge my deepest gratitude to the professors and friends who encouraged and inspired me, who gave their pri vate time willingly, who supported me with their thoughts whenever they felt my need, and especially to all the members of my Graduate Committee, Professor Hoyt Sherman, Professor Franklin Ludden, Professor Francis Utley, Professor Robert King, and Professor Paul Bogatay. ii CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.............................. ii ILLUSTRATIONS................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION................................................................................... 1 Chapter I. CONTEMPORARY ART OF THE UNITED ARAB REPUBLIC.............................. 4 The Pioneers of Contemporary Egyptian Art Artists of the School of Fine Arts Artists of the School of Decorative Arts (The School of Applied Arts) The "free artists" The Pioneers of Art Education The Pioneers of Art Criticism The Art Movements Types of Contemporary Art Criticism in the United Arab Republic Summary H. ARA B NA TIONALISM AND ARA B CULTURE................ 21 Definition of nationalism Arab Faith and Culture The Influence of Cultures The Islam Influence on the Arts Summary Chapter Page m. -

The Pseudo-Kufic Ornament and the Problem of Cross-Cultural Relationships Between Byzantium and Islam

The pseudo-kufic ornament and the problem of cross-cultural relationships between Byzantium and Islam Silvia Pedone – Valentina Cantone The aim of the paper is to analyze pseudo-kufic ornament Dealing with a much debated topic, not only in recent in Byzantine art and the reception of the topic in Byzantine times, as that concerning the role and diffusion of orna- Studies. The pseudo-kufic ornamental motifs seem to ment within Byzantine art, one has often the impression occupy a middle position between the purely formal that virtually nothing new is possible to add so that you abstractness and freedom of arabesque and the purely have to repeat positions, if only involuntarily, by now well symbolic form of a semantic and referential mean, borrowed established. This notwithstanding, such a topic incessantly from an alien language, moreover. This double nature (that gives rise to questions and problems fueling the discussion is also a double negation) makes of pseudo-kufic decoration of historical and theoretical issues: a debate that has been a very interesting liminal object, an object of “transition”, going on for longer than two centuries. This situation is as it were, at the crossroad of different domains. Starting certainly due to a combination of reasons, but ones hav- from an assessment of the theoretical questions raised by ing a close connection with the history of the art-historical the aesthetic peculiarities of this kind of ornament, we discipline itself. In the present paper our aim is to focus on consider, from this specific point of view, the problem of a very specific kind of ornament, the so-called pseudo-kufic the cross-cultural impact of Islamic and islamicizing formal inscriptions that rise interesting pivotal questions – hither- repertory on Byzantine ornament, focusing in particular on to not so much explored – about the “interference” between a hitherto unpublished illuminated manuscript dated to the a formalistic approach and a functionalistic stance, with its 10th century and held by the Marciana Library in Venice. -

Western Europe 13

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 687 Behind the Scenes SEND US YOUR FEEDBACK We love to hear from travellers – your comments keep us on our toes and help make our books better. Our well-travelled team reads every word on what you loved or loathed about this book. Although we cannot reply individually to your submissions, we always guarantee that your feed- back goes straight to the appropriate authors, in time for the next edition. Each person who sends us information is thanked in the next edition – the most useful submissions are rewarded with a selection of digital PDF chapters. Visit lonelyplanet.com/contact to submit your updates and suggestions or to ask for help. Our award-winning website also features inspirational travel stories, news and discussions. Note: We may edit, reproduce and incorporate your comments in Lonely Planet products such as guidebooks, websites and digital products, so let us know if you don’t want your comments reproduced or your name acknowledged. For a copy of our privacy policy visit lonelyplanet.com/ privacy. OUR READERS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many thanks to the travellers who used Climate map data adapted from Peel MC, Finlayson the last edition and wrote to us with help- BL & McMahon TA (2007) ‘Updated World Map of the ful hints, useful advice and interesting Köppen-Geiger Climate Classification’, Hydrology and anecdotes: Adrienne Nielsen, Max Dickinson, Earth System Sciences, 11, 163344. Stella Italiano, Yeonghoon Kim Cover photograph: Hand of Constantine the Great statue, Capitoline Museums, Rome. Stefano Politi WRITER THANKS Markovina / AWL © Catherine Le Nevez Merci mille fois first and foremost to Julian, and to everyone throughout Western Europe who has provided insights and inspiration over the years. -

Palermo Arabnorma.Pdf

PALERMO Patrimonio Unesco Coordinamento editoriale Fabrizio Rubino Art Director e fotografie Lamberto Rubino Prefazione Fabio Granata Testi Aurelio Angelini Roberto Alajmo Sebastiano Tusa Testo Immaginario Pietrangelo Buttafuoco Traduzioni Susanna Kimbell Editor e testi didascalici Maria Elisabetta Giarratana Impaginazione e grafica Greta Caruso Distribuzione Ivan Federico Segretaria di produzione Monica Genovese Stampa Effe grafica Fratantonio - Pachino (Sr) © Copyright 2015 Società Produzione Immagini s.a.s. Linea editoriale Erre Produzioni - Collana le Sicilie www.erreproduzioni.it [email protected] www.lesicilie.it [email protected] Tutti i diritti riservati ISBN: 978-88-87909-42-5 In copertina Mosaici della sala di Re Ruggero, particolare. Palazzo Reale, Palermo In quarta di copertina Cattedrale, Palermo Opere in prefazione Decorazioni a mosaico interne, Cattedrale di Monreale (pp. 1, 4, 7, 12, 14, 16) Mosaico con pavoni, Palazzo della Zisa, Palermo (p. 3) Stanza di Re Ruggero, particolare. Palazzo Reale, Palermo (pp. 8, 11) industriali connesse con la trasformazione dei prodotti e la loro commercializzazione. Espressione emblematica della capacità manifatturiera dell’isola in quel felice frangente è il manto di Ruggero II, realizzato presso le officine reali nel 1133, in seta rossa con ricami in oro raffiguranti due leoni che azzannano altrettanti cammelli con al centro una palma; dimostrando ancora una volta la felice commistione di iconografie diverse (conservato a Vienna press il Kunsthistorisches Museum). Prerequisito vitale e decisivo per tale fulgido momento di brillante sviluppo globale dell’i- sola (ed è qui che risiede l’attualità, oltre che la legittimità, della “lezione arabo-norman- na” oggi rinvigorita dall’imminente riconoscimento UNESCO) fu la saggia e illuminata poli- tica ruggeriana basata sui principi della tolleranza e dell’interculturalità. -

Città, Terre E Casali

Capitolo primo CITTÀ, TERRE E CASALI 1.1 IL TERRITORIO La Provincia di Basilicata confinava a nord con il Principato Ultra e con la Capitanata, a est con la Terra di Bari e con la Terra d'Otranto, a sud con la Calabria Citra, a ovest con il Principato Citra (CARTINA 2). Essa trovava la sua unità più in elementi storico - amministrativi che nella struttura morfologica e geografica:17 era "dentro di terra e senza grandi città",18 oltre ad essere "la più chiusa e la men nota di tutte le province del regno";19 a tutto ciò si aggiungeva l'assenza pressoché totale delle vie di comunicazione. La delineazione territoriale è il punto di partenza per meglio analizza- re il rapporto fra territorio e popolazione, da un lato, e le dinamiche eco- nomiche e sociali da esso derivanti, dall'altro. Questa condizione di isolamento geografico costituì la premessa della prevalente chiusura economica e del debole sviluppo sociale di tale pro- vincia, quasi tagliata fuori da ogni rotta commerciale sia marittima, "non aveva porti sul mare e le poche spanne di costa affatto inapprodabili",20 che terrestre, essendo questo un territorio impraticabile "e per catene di montagne, per mal sicure boscaglie, per ripide balze e per vie dirupate o mal ferme sul suolo cretaceo che si scioglie e si frana, la più impervia, la meno accessibile".21 Questa condizione topografica "stranamente singolare",22 che rende- 17 P. Villani, F. Volpe, Territorio e popolazione della Basilicata nell'età moderna, in AA. VV., Società e religione in Basilicata, Roma 1978, vol. I, p.