Islamic Traditions in Malabar: Boundaries, Appropriations and Resistances

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Synonym to Conservation of Intangible Cultural Heritage: Folkland, International Centre for Folklore and Culture, Heading for Its 30Th Anniversary

A Synonym to Conservation of Intangible Cultural Heritage: Folkland, International Centre for Folklore and Culture, Heading for Its 30th Anniversary V. Jayarajan Folkland, International Centre for Folklore and Culture Folkland, International Centre for Folklore and Culture is an institution that was first registered on December 20, 1989 under the Societies Registration Act of 1860, vide No. 406/89. Over the last 16 years, it has passed through various stages of growth, especially in the fields of performance, production, documentation, and research, besides the preservation of folk art and culture. Since its inception in 1989, Folkland has passed through various phases of growth into a cultural organization with a global presence. As stated above, Folkland has delved deep into the fields of stage performance, production, documentation, and research, besides the preservation of folk art and culture. It has strived hard and treads the untrodden path with a clear motto of preservation and inculcation of old folk and cultural values in our society. Folkland has a veritable collection of folk songs, folk art forms, riddles, fables, myths, etc. that are on the verge of extinction. This collection has been recorded and archived well for scholastic endeavors and posterity. As such, Folkland defines itself as follows: 1. An international center for folklore and culture. 2. A cultural organization with clearly defined objectives and targets for research and the promotion of folk arts. Folkland has branched out and reached far and wide into almost every nook and corner of the world. The center has been credited with organizing many a festival on folk arts or workshop on folklore, culture, linguistics, etc. -

Authority, Knowledge and Practice in Unani Tibb in India, C. 1890

Authority, Knowledge and Practice in UnaniTibb in India, c. 1890 -1930 Guy Nicolas Anthony Attewell Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London ProQuest Number: 10673235 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673235 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This thesis breaks away from the prevailing notion of unanitibb as a ‘system’ of medicine by drawing attention to some key arenas in which unani practice was reinvented in the early twentieth century. Specialist and non-specialist media have projected unani tibb as a seamless continuation of Galenic and later West Asian ‘Islamic’ elaborations. In this thesis unani Jibb in early twentieth-century India is understood as a loosely conjoined set of healing practices which all drew, to various extents, on the understanding of the body as a site for the interplay of elemental forces, processes and fluids (humours). The thesis shows that in early twentieth-century unani ///)/; the boundaries between humoral, moral, religious and biomedical ideas were porous, fracturing the realities of unani practice beyond interpretations of suffering derived from a solely humoral perspective. -

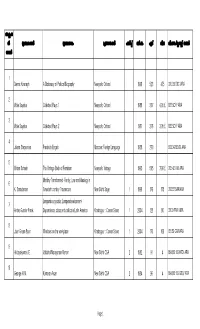

V. Aravindakshan 2.Xlsx

അക്സഷ ന് ഗര്ന്ഥകാരന് ഗര്ന്ഥനാമം പര്സാധകന് പതിപ്പ് വര്ഷംഏട്വിലവിഷയം/കല്ാസ്സ് നമ്പര് നമ്പര് 1 Dennis Kavnagh A Dictionary of Political Biography Newyork: Oxford 1998 523 475 320.092 DIC /ARA 2 Wole Soyinka Collected Plays 1 Newyork: Oxford 1988 307 4.95 £ 822 SOY/ ARA 3 Wole Soyinka Collected Plays 2 Newyork: Oxford 1987 276 3.95 £ 822 SOY/ ARA 4 Jelena Stepanova Frederick Engels Moscow: Foreign Language 1958 270 923.343 ENG/ ARA 5 Miriam Schneir The Vintage Book of Feminism Newyork: Vintage 1995 505 7.99 £ 305.42 VIN/ ARA 6 Matriliny Transformed -Family, Law and Ideology in K. Saradamoni Twenteth century Travancore New Delhi: Sage 1 1999 176 175 306.83 SAR/ARA 7 Lumpenbourgeoisle: Lumpendevelopment- Andre Gunder Frank Dependence, class and politics in Latin America Khabagpur : Corner Stone 1 2004 128 80 320.9 FRA/ ARA 8 Joan Green Baun Windows on the workplace Khabagpur : Corner Stone 1 2004 170 100 651.59 GRA/ARA 9 Hridayakumari. E. Vallathol Narayanan Menon New Delhi: CSA 2 1982 91 4 894.812 109 HRD/ ARA 10 George. K.M. Kumaran Asan New Delhi: CSA 2 1984 96 4 894.812 109 GEO/ ARA Page 1 11 Tharakan. K.M. M.P. Paul New Delhi: CSA 1 1985 96 4 894.812 109 THA/ ARA 12 335.43 AJI/ARA Ajit Roy Euro-Communism' An Analytical story Calcutta: Pearl 88 10 13 801.951 MAC/ARA Archi Bald Macleish Poetry and Experience Australia: Penguin Books 1960 187 Alien Homage' -Edward Thompson and 14 891.4414 THO/ARA E.P. Thompson Rabindranath Tagore New Delhi : Oxford 2 1998 175 275 15 894.812309 VIS/ARA R.Viswanathan Pottekkatt New Delhi: CSA 1 1998 60 5 16 891.73 CHE/ARA A.P. -

Particulars of Some Temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of Some

Particulars of some temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of some temples of Kerala .............................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 9 Temples of Kerala ................................................................................. 10 Temples of Kerala- an over view .................................................... 16 1. Achan Koil Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 23 2. Alathiyur Perumthiri(Hanuman) koil ................................. 24 3. Randu Moorthi temple of Alathur......................................... 27 4. Ambalappuzha Krishnan temple ........................................... 28 5. Amedha Saptha Mathruka Temple ....................................... 31 6. Ananteswar temple of Manjeswar ........................................ 35 7. Anchumana temple , Padivattam, Edapalli....................... 36 8. Aranmula Parthasarathy Temple ......................................... 38 9. Arathil Bhagawathi temple ..................................................... 41 10. Arpuda Narayana temple, Thirukodithaanam ................. 45 11. Aryankavu Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 47 12. Athingal Bhairavi temple ......................................................... 48 13. Attukkal BHagawathy Kshethram, Trivandrum ............. 50 14. Ayilur Akhileswaran (Shiva) and Sri Krishna temples ........................................................................................................... -

Minority Media and Community Agenda Setting a Study on Muslim Press in Kerala

Minority Media and Community Agenda Setting A Study On Muslim Press In Kerala Muhammadali Nelliyullathil, Ph.D. Dean, Faculty of Journalism and Head, Dept. of Mass Communication University of Calicut, Kerala India Abstract Unlike their counterparts elsewhere in the country, Muslim newspapers in Kerala are highly professional in staffing, payment, and news management and production technology and they enjoy 35 percent of the newspaper readership in Kerala. They are published in Malayalam when Indian Muslim Press outside Kerala concentrates on Urdu journalism. And, most of these newspapers have a promising newsroom diversity employing Muslim and non-Muslim women, Dalits and professionals from minority and majority religions. However, how effective are these newspapers in forming public opinion among community members and setting agendas for community issues in public sphere? The study, which is centered on this fundamental question and based on the conceptual framework of agenda setting theory and functional perspective of minority media, examines the role of Muslim newspapers in Kerala in forming a politically vibrant, progress oriented, Muslim community in Kerala, bringing a collective Muslim public opinion into being, Influencing non-Muslim media programming on Muslim issues and influencing the policy agenda of the Government on Muslim issues. The results provide empirical evidences to support the fact that news selection and presentation preferences and strategies of Muslim newspapers in Kerala are in line with Muslim communities’ news consumption pattern and related dynamics. Similarly, Muslim public’s perception of community issues are formed in accordance with the news framing and priming by Muslim newspapers in Kerala. The findings trigger more justifications for micro level analysis of the functioning of the Muslim press in Kerala to explore the community variable in agenda setting schema and the significance of minority press in democratic political context. -

List of Teachers Posted from the Following Schools to Various Examination Centers As Assistant Superintendents for Higher Secondary Exam March 2015

LIST OF TEACHERS POSTED FROM THE FOLLOWING SCHOOLS TO VARIOUS EXAMINATION CENTERS AS ASSISTANT SUPERINTENDENTS FOR HIGHER SECONDARY EXAM MARCH 2015 08001 - GOVT SMT HSS,CHELAKKARA,THRISSUR 1 DILEEP KUMAR P V 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR 04884231495, 9495222963 2 SWAPNA P 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR , 9846374117 3 SHAHINA.K 08035-GOVT. RSR VHSS, VELUR, THRISSUR 04885241085, 9447751409 4 SEENA M 08041-GOVT HSS,PAZHAYANNOOR,THRISSUR 04884254389, 9447674312 5 SEENA P.R 08046-AKM HSS,POOCHATTY,THRISSUR 04872356188, 9947088692 6 BINDHU C 08062-ST ANTONY S HSS,PUDUKAD,THRISSUR 04842331819, 9961991555 7 SINDHU K 08137-GOVT. MODEL HSS FOR GIRLS, THRISSUR TOWN, , 9037873800 THRISSUR 8 SREEDEVI.S 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR , 9020409594 9 RADHIKA.R 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR 04742552608, 9847122431 10 VINOD P 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR , 9446146634 11 LATHIKADEVI L A 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR 04742482838, 9048923857 12 REJEESH KUMAR.V 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR 04762831245, 9447986101 08002 - GOVT HSS,CHERPU,THRISSUR 1 PREETHY M K 08003-GOVT MODEL GHSS, IRINJALAKKUDA, THRISSUR 04802820505, 9496288495 2 RADHIKA C S 08003-GOVT MODEL GHSS, IRINJALAKKUDA, THRISSUR , 9495853650 3 THRESSIA A.O 08005-GOVT HSS,KODAKARA,THRISSUR 04802726280, 9048784499 4 SMITHA M.K 08046-AKM HSS,POOCHATTY,THRISSUR 04872317979, 8547619054 5 RADHA M.R 08050-ST ANTONY S HSS,AMMADAM,THRISSUR 04872342425, 9497180518 6 JANITHA K 08050-ST ANTONY S HSS,AMMADAM,THRISSUR 04872448686, 9744670871 1 7 SREELEKHA.E.S 08050-ST ANTONY S HSS,AMMADAM,THRISSUR 04872343515, 9446541276 8 APINDAS T T 08095-ST. PAULS CONVENT EHSS KURIACHIRA, THRISSUR, 04872342644, 9446627146 680006 9 M.JAMILA BEEVI 08107-SN GHSS, KANIMANGALAM, THRISSUR, 680027 , 9388553667 10 MANJULA V R 08118-TECHNICAL HSS, VARADIAM, THRISSUR, 680547 04872216227, 9446417919 11 BETSY C V 08138-GOVT. -

PONNANI PEPPER PROJECT History Ponnani Is Popularly Known As “The Mecca of Kerala”

PONNANI PEPPER PROJECT HISTORY Ponnani is popularly known as “the Mecca of Kerala”. As an ancient harbour city, it was a major trading hub in the Malabar region, the northernmost end of the state. There are many tales that try to explain how the place got its name. According to one, the prominent Brahmin family of Azhvancherry Thambrakkal once held sway over the land. During their heydays, they offered ponnu aana [elephants made of gold] to the temples, and this gave the land the name “Ponnani”. According to another, due to trade, ponnu [gold] from the Arab lands reached India for the first time at this place, and thus caused it to be named “Ponnani”. It is believed that a place that is referred to as “Tyndis” in the Greek book titled Periplus of the Erythraean Sea is Ponnani. However historians have not been able to establish the exact location of Tyndis beyond doubt. Nor has any archaeological evidence been recovered to confirm this belief. Politically too, Ponnani had great importance in the past. The Zamorins (rulers of Calicut) considered Ponnani as their second headquarters. When Tipu Sultan invaded Kerala in 1766, Ponnani was annexed to the Mysore kingdom. Later when the British colonized the land, Ponnani came under the Bombay Province for a brief interval of time. Still later, it was annexed Malabar and was considered part of the Madras Province for one-and-a-half centuries. Until 1861, Ponnani was the headquarters of Koottanad taluk, and with the formation of the state of Kerala in 1956, it became a taluk in Palakkad district. -

6. Understanding the Epistemology of Talaq

2016 (2) Elen. L R 6. UNDERSTANDING THE EPISTEMOLOGY OF TALAQ UNDER THE SHARIAT LAW Neema Noor Mohamed1 Introduction “Talaq” has turned out to be one of the most debated topic in the recent past in the contemporary India. Indian Muslim women living in the 21st century globalising world had to be the victims of the most arbitrary practice called “Triple Talaq” that legally prevailed in India until the historic judgement delivered by the constitutional Bench of Supreme court through ShayaraBano and others vs Union of India. This is a time to retrospect what made India, the largest democratic country to take such a long time to abolish this unislamic and unconstitutional practice, which has been abolished even by those countries where Shariat is the law of the land. This practice of triple Talaq was totally in contradiction with the law of divorce as held in the Quran. The sad reality is that divorce especially in the form of Talaq (divorce by husband) is the most misinterpreted incident leading to much suffering to the Muslim women. To quote Noel James Coulson, “without doubt it is the institution of Talaq which stands out in the whole range of the family law as occasioning the gravest prejudice to the status of Muslim women” (Quoted in Pearl and Meski 1988: 286). To a vast extend during his lifetime; Prophet Mohammad (PBUH) through his intellectualism and divinity, brought systematisation and Islamicization in every aspect of human conduct and relations. Unfortunately after the death of Prophet, his followers could not take up the legacy with the time and space which led to havoc in various aspects of Islamic Jurisprudence. -

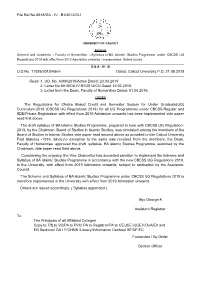

U.O.No. 11099/2019/Admn Dated, Calicut University.P.O, 21.08.2019 Biju George K Assistant Registrar Forwarded / by Order Section

File Ref.No.8818/GA - IV - B1/2012/CU UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT Abstract General and Academic - Faculty o f Humanities - Syllabus o f BA Islamic Studies Programme under CBCSS UG Regulations 2019 with effect from 2019 Admission onwards - Implemented- Orders issued G & A - IV - B U.O.No. 11099/2019/Admn Dated, Calicut University.P.O, 21.08.2019 Read:-1. UO. No. 4368/2019/Admn Dated: 23.03.2019 2. Letter No.8818/GA IV B1/2012/CU Dated:15.06.2019. 3. Letter from the Dean, Faculty of Humanities Dated: 01.08.2019. ORDER The Regulations for Choice Based Credit and Semester System for Under Graduate(UG) Curriculum-2019 (CBCSS UG Regulations 2019) for all UG Programmes under CBCSS-Regular and SDE/Private Registration with effect from 2019 Admission onwards has been implemented vide paper read first above. The draft syllabus of BA Islamic Studies Programme, prepared in tune with CBCSS UG Regulation- 2019, by the Chairman, Board of Studies in Islamic Studies, was circulated among the members of the Board of Studies in Islamic Studies vide paper read second above as provided under Calicut University First Statutes -1976. Since,no exception to the same was received from the members, the Dean, Faculty of Humanities approved the draft syllabus BA Islamic Studies Programme, submited by the Chairman, vide paper read third above. Considering the urgency, the Vice Chancellor has accorded sanction to implement the Scheme and Syllabus of BA Islamic Studies Programme in accordance with the new CBCSS UG Regulations 2019, in the University, with effect from 2019 Admission onwards, subject to ratification by the Academic Council. -

Dictionary of Martyrs: India's Freedom Struggle

DICTIONARY OF MARTYRS INDIA’S FREEDOM STRUGGLE (1857-1947) Vol. 5 Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu & Kerala ii Dictionary of Martyrs: India’s Freedom Struggle (1857-1947) Vol. 5 DICTIONARY OF MARTYRSMARTYRS INDIA’S FREEDOM STRUGGLE (1857-1947) Vol. 5 Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu & Kerala General Editor Arvind P. Jamkhedkar Chairman, ICHR Executive Editor Rajaneesh Kumar Shukla Member Secretary, ICHR Research Consultant Amit Kumar Gupta Research and Editorial Team Ashfaque Ali Md. Naushad Ali Md. Shakeeb Athar Muhammad Niyas A. Published by MINISTRY OF CULTURE, GOVERNMENT OF IDNIA AND INDIAN COUNCIL OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH iv Dictionary of Martyrs: India’s Freedom Struggle (1857-1947) Vol. 5 MINISTRY OF CULTURE, GOVERNMENT OF INDIA and INDIAN COUNCIL OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH First Edition 2018 Published by MINISTRY OF CULTURE Government of India and INDIAN COUNCIL OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH 35, Ferozeshah Road, New Delhi - 110 001 © ICHR & Ministry of Culture, GoI No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN 978-81-938176-1-2 Printed in India by MANAK PUBLICATIONS PVT. LTD B-7, Saraswati Complex, Subhash Chowk, Laxmi Nagar, New Delhi 110092 INDIA Phone: 22453894, 22042529 [email protected] State Co-ordinators and their Researchers Andhra Pradesh & Telangana Karnataka (Co-ordinator) (Co-ordinator) V. Ramakrishna B. Surendra Rao S.K. Aruni Research Assistants Research Assistants V. Ramakrishna Reddy A.B. Vaggar I. Sudarshan Rao Ravindranath B.Venkataiah Tamil Nadu Kerala (Co-ordinator) (Co-ordinator) N. -

Ali Musliyar Scholar Turned Freedom Fighter-Malabar Pages

ALI MUSLIYAR SCHOLAR TURNED FREEDOM FIGHTER-MALABAR PAGES Hussain Randathani 1 In Malabar, on the coast of Arabian sea in South India, Musliyar is a familiar epithet to the Islamic scholars. The word owes it s origin to Arabic and Tamil, a south Indian language- Muslih an Arabic term meaning, one who refine and yar a honorific title used in the area. The word was coined by the Makhdums as a degree to those who completed their studies in the Ponnani mosque Academy and later it came to be used to all those who performed religious duties. The Musliyars, hither to remained as religious heads turned into politics during colonial period starting from 1498 with the coming o the Portuguese on the coast. Muslims, as a trading community had become influential in the area through their trade and naval fights against the colonial invaders. Islam is said to had reached on the coast during the time of the prophet Muhammad, ie., in the seventh century, and prospered through trade and conversion making the land a house of Islam (Dar al Islam). The local rulers provided facilities to the Muslim sufi missionaries accompanying the traders, to prosper themselves and the presence of Islam naturally did away with caste restrictions which had been the oar of discrimination in Malabar society. Ali Musliyar (1854-1922), as told above, belonged to the family of scholars of Malabar, residing at the present Nellikkuthu, 8 Kilometer away on Manjeri Mannarkkad Road in the district of Malappuram, in South India. The Place is a Muslim dominated area, people engaging mainly in agriculture and petty trades. -

Manchester Muslims: the Developing Role of Mosques, Imams and Committees with Particular Reference to Barelwi Sunnis and UKIM

Durham E-Theses Manchester Muslims: The developing role of mosques, imams and committees with particular reference to Barelwi Sunnis and UKIM. AHMED, FIAZ How to cite: AHMED, FIAZ (2014) Manchester Muslims: The developing role of mosques, imams and committees with particular reference to Barelwi Sunnis and UKIM., Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10724/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 DURHAM UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY Manchester Muslims: The developing role of mosques, imams and committees with particular reference to Barelwi Sunnis and UKIM. Fiaz Ahmed September 2013 Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief it contains no material previously published or written by another person except where dueacknowledgement has been made in the text.