Muslim Entrepreneurs in Public Life Between India and the Gulf: Making Good and Doing Good

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stephen Philip Cohen the Idea Of

00 1502-1 frontmatter 8/25/04 3:17 PM Page iii the idea of pakistan stephen philip cohen brookings institution press washington, d.c. 00 1502-1 frontmatter 8/25/04 3:17 PM Page v CONTENTS Preface vii Introduction 1 one The Idea of Pakistan 15 two The State of Pakistan 39 three The Army’s Pakistan 97 four Political Pakistan 131 five Islamic Pakistan 161 six Regionalism and Separatism 201 seven Demographic, Educational, and Economic Prospects 231 eight Pakistan’s Futures 267 nine American Options 301 Notes 329 Index 369 00 1502-1 frontmatter 8/25/04 3:17 PM Page vi vi Contents MAPS Pakistan in 2004 xii The Subcontinent on the Eve of Islam, and Early Arab Inroads, 700–975 14 The Ghurid and Mamluk Dynasties, 1170–1290 and the Delhi Sultanate under the Khaljis and Tughluqs, 1290–1390 17 The Mughal Empire, 1556–1707 19 Choudhary Ramat Ali’s 1940 Plan for Pakistan 27 Pakistan in 1947 40 Pakistan in 1972 76 Languages of Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Northwest India 209 Pakistan in Its Larger Regional Setting 300 01 1502-1 intro 8/25/04 3:18 PM Page 1 Introduction In recent years Pakistan has become a strategically impor- tant state, both criticized as a rogue power and praised as being on the front line in the ill-named war on terrorism. The final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States iden- tifies Pakistan, along with Afghanistan and Saudi Arabia, as a high- priority state. This is not a new development. -

U.O.No. 11099/2019/Admn Dated, Calicut University.P.O, 21.08.2019 Biju George K Assistant Registrar Forwarded / by Order Section

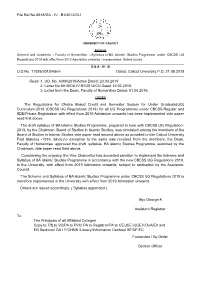

File Ref.No.8818/GA - IV - B1/2012/CU UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT Abstract General and Academic - Faculty o f Humanities - Syllabus o f BA Islamic Studies Programme under CBCSS UG Regulations 2019 with effect from 2019 Admission onwards - Implemented- Orders issued G & A - IV - B U.O.No. 11099/2019/Admn Dated, Calicut University.P.O, 21.08.2019 Read:-1. UO. No. 4368/2019/Admn Dated: 23.03.2019 2. Letter No.8818/GA IV B1/2012/CU Dated:15.06.2019. 3. Letter from the Dean, Faculty of Humanities Dated: 01.08.2019. ORDER The Regulations for Choice Based Credit and Semester System for Under Graduate(UG) Curriculum-2019 (CBCSS UG Regulations 2019) for all UG Programmes under CBCSS-Regular and SDE/Private Registration with effect from 2019 Admission onwards has been implemented vide paper read first above. The draft syllabus of BA Islamic Studies Programme, prepared in tune with CBCSS UG Regulation- 2019, by the Chairman, Board of Studies in Islamic Studies, was circulated among the members of the Board of Studies in Islamic Studies vide paper read second above as provided under Calicut University First Statutes -1976. Since,no exception to the same was received from the members, the Dean, Faculty of Humanities approved the draft syllabus BA Islamic Studies Programme, submited by the Chairman, vide paper read third above. Considering the urgency, the Vice Chancellor has accorded sanction to implement the Scheme and Syllabus of BA Islamic Studies Programme in accordance with the new CBCSS UG Regulations 2019, in the University, with effect from 2019 Admission onwards, subject to ratification by the Academic Council. -

Cellphones, Is Times

y k y cm IN HIGH SPIRITS NEPAL POLITICAL CRISIS DENMARK ADVANCE Actor Rakul Preet Singh has returned Nepal SC Tuesday ruled that the appointment of 20 Denmark thrash Russia 4-1 in their last group- to the shooting set and called it her ministers by KP Sharma Oli was stage game to qualify for the knockout round at Euro 2020 happy mode LEISURE | P2 unconstitutional INTERNATIONAL | P10 SPORTS | P12 VOLUME 11, ISSUE 83 | www.orissapost.com BHUBANESWAR | WEDNESDAY, JUNE 23 | 2021 12 PAGES | `5.00 SNANA YATRA Section 144 to be clamped in Puri POST NEWS NETWORK Puri, June 22: The Puri district ad- ministration has decided to promul- gate Section 144 CrPC for the smooth conduct of Snana Yatra (divine bathing rituals of Lord Jagannath and his siblings) scheduled to be performed June 24. The restriction will come into force Heavy rains to lash at 10 pm June 23 and will continue till June25, Sub-Collector Bhabataran Sahoo said. No unauthorised person Odisha till June 26 will be allowed to enter Puri during IRREGULAR by MANJUL the period and violators will be dealt with strictly, he added. The decision POST NEWS NETWORK Dhenkanal, Keonjhar, has been taken in view of the Covid Mayurbhanj, Bolangir, pandemic so that the ceremonial bath Bhubaneswar, June 22: Sonepur, Boudh, Kalahandi, of the Trinities can be held without Heavy rains are likely to Kandhamal, Nayagarh and public participation. lash several parts of the Khurda districts are likely The administration appealed to state till June 26. to wintess thunderstorm the residents of Puri and devotees to The regional office of the and lightning Thursday,” cooperate with the temple authori- India Meteorological the MET said Tuesday. -

Jihadist Violence: the Indian Threat

JIHADIST VIOLENCE: THE INDIAN THREAT By Stephen Tankel Jihadist Violence: The Indian Threat 1 Available from : Asia Program Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20004-3027 www.wilsoncenter.org/program/asia-program ISBN: 978-1-938027-34-5 THE WOODROW WILSON INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR SCHOLARS, established by Congress in 1968 and headquartered in Washington, D.C., is a living national memorial to President Wilson. The Center’s mission is to commemorate the ideals and concerns of Woodrow Wilson by providing a link between the worlds of ideas and policy, while fostering research, study, discussion, and collaboration among a broad spectrum of individuals concerned with policy and scholarship in national and interna- tional affairs. Supported by public and private funds, the Center is a nonpartisan insti- tution engaged in the study of national and world affairs. It establishes and maintains a neutral forum for free, open, and informed dialogue. Conclusions or opinions expressed in Center publications and programs are those of the authors and speakers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Center staff, fellows, trustees, advisory groups, or any individuals or organizations that provide financial support to the Center. The Center is the publisher of The Wilson Quarterly and home of Woodrow Wilson Center Press, dialogue radio and television. For more information about the Center’s activities and publications, please visit us on the web at www.wilsoncenter.org. BOARD OF TRUSTEES Thomas R. Nides, Chairman of the Board Sander R. Gerber, Vice Chairman Jane Harman, Director, President and CEO Public members: James H. -

Urdu and the Racialized- Decastification of the “Backward Musalmaan” in India

Article CASTE: A Global Journal on Social Exclusion Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 175–199 February 2020 brandeis.edu/j-caste ISSN 2639-4928 DOI: 10.26812/caste.v1i1.29 The Identity of Language and the Language of Erasure: Urdu and the Racialized- Decastification of the “Backward Musalmaan” in India Sanober Umar1 (Bluestone Rising Scholar Honorable Mention 2019) Abstract The decline of Urdu in post-colonial Uttar Pradesh has often been studied alongside the fall of Muslim representation in public services and the ‘job market’ in independent India. However, there remains a severe dearth in scholarship that intertwines the tropes surrounding Urdu as ‘foreign’ to India and the role that the racialization of the language played in insidiously collaborating with post-colonial governmentality which problematically ‘decastified’ and therefore circumscribed the production of ‘Muslim minority’ citizen identity. I argue that since the 1950s the polemics of Urdu and reasons cited for its lack of institutional recognition as a regional/linguistic minority language in Uttar Pradesh (until 1994) significantly informed the constitutional construction of ‘the casteless Muslim’ in the same stage setting era of the 1950s. These seemingly disparate sites of language and caste worked together to systematically deprive some of the most marginalised lower caste and Dalit Muslims access to affirmative action as their cultural-political economies witnessed a drastic fall in the early decades after Partition. This article addresses the connections between the production -

UNIT 16 MUSLIM SOCIAL ORGANISATION Muslim Social Organisation

UNIT 16 MUSLIM SOCIAL ORGANISATION Muslim Social Organisation Structure 16.0 Objectives 16.1 Introduction 16.2 Emergence of Islam and Muslim Community in India 16.3 Tenets of Islam: View on Social Equality 16.4 Aspects of Social Organisation 16.4.1 Social Divisions among Muslims 16.4.2 Caste and Kin Relationships 16.4.3 Social Control 16.4.4 Family, Marriage and Inheritance 16.4.5 Life Cycle Rituals arid Festivals 16.5 External Influence on Muslim Social Practices 16.6 Let Us Sum Up 16.7 Keywords 16.8 Further Reading 16.9 Specimen Answers to Check Your Progress 16.0 OBJECTIVES On going through this unit you should be able to z describe briefly the emergence of Islam and Muslim community in India z list and describe the basic tenets of Islam with special reference to its views on social equality z explain the social divisions among the Muslims z describe the processes involved in the maintenance of social control in the Islamic community z describe the main features of Muslim marriage, family and systems of inheritance z list the main festivals celebrated by the Muslims z indicate some of the external influences on Muslim social practices. 16.1 INTRODUCTION In the previous unit we examined the various facets of Hindu Social Organisation. In this unit we are going to look at some important aspects of Muslim social organisation. We begin our examination with an introductory note on the emergence of Islam and the Muslim community in India. We will proceed to describe the central tenets of Islam, elaborating the view of Islam on social equality, in a little more detail. -

Manual of Instructions for Editing, Coding and Record Management of Individual Slips

For offiCial use only CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 MANUAL OF INSTRUCTIONS FOR EDITING, CODING AND RECORD MANAGEMENT OF INDIVIDUAL SLIPS PART-I MASTER COPY-I OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR GENERAL&. CENSUS COMMISSIONER. INOI.A MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS NEW DELHI CONTENTS Pages GENERAlINSTRUCnONS 1-2 1. Abbreviations used for urban units 3 2. Record Management instructions for Individual Slips 4-5 3. Need for location code for computer processing scheme 6-12 4. Manual edit of Individual Slip 13-20 5. Code structure of Individual Slip 21-34 Appendix-A Code list of States/Union Territories 8a Districts 35-41 Appendix-I-Alphabetical list of languages 43-64 Appendix-II-Code list of religions 66-70 Appendix-Ill-Code list of Schedules Castes/Scheduled Tribes 71 Appendix-IV-Code list of foreign countries 73-75 Appendix-V-Proforma for list of unclassified languages 77 Appendix-VI-Proforma for list of unclassified religions 78 Appendix-VII-Educational levels and their tentative equivalents. 79-94 Appendix-VIII-Proforma for Central Record Register 95 Appendix-IX-Profor.ma for Inventory 96 Appendix-X-Specimen of Individual SHp 97-98 Appendix-XI-Statement showing number of Diatricts/Tehsils/Towns/Cities/ 99 U.AB.lC.D. Blocks in each State/U.T. GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS This manual contains instructions for editing, coding and record management of Individual Slips upto the stage of entry of these documents In the Direct Data Entry System. For the sake of convenient handling of this manual, it has been divided into two parts. Part·1 contains Management Instructions for handling records, brief description of thf' process adopted for assigning location code, the code structure which explains the details of codes which are to be assigned for various entries in the Individual Slip and the edit instructions. -

Ancestral Centers of Kerala Muslim Socio- Cultural and Educational Enlightenments Dr

© 2019 JETIR June 2019, Volume 6, Issue 6 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Ancestral Centers of Kerala Muslim Socio- Cultural and Educational Enlightenments Dr. A P Alavi Bin Mohamed Bin Ahamed Associate Professor of Islamic history Post Graduate and Research Department of Islamic History, Government College, Malappuram. Abstract: This piece of research paper attempts to show that the genesis and growth of Islam, a monotheistic religion in Kerala. Of the Indian states, Malabar was the most important state with which the Arabs engaged in trade from very ancient time. Advance of Islam in Kerala,it is even today a matter of controversy. Any way as per the established authentic historical records, we can definitely conclude that Islam reached Kerala coast through the peaceful propagation of Arab-Muslim traders during the life time of prophet Muhammad. Muslims had been the torch bearers of knowledge and learning during the middle ages. Traditional education centres, i.e Maqthabs, Othupallis, Madrasas and Darses were the ancestral centres of socio-cultural and educational enlightenments, where a new language, Arabic-Malayalam took its birth. It was widely used to impart educational process and to exhort anti-colonial feelings and religious preaching in Medieval Kerala. Keywords: Darses, Arabi-Malayalam, Othupalli, Madrasa. Introduction: Movements of revitalization, renewal and reform are periodically found in the glorious history of Islam since its very beginning. For higher religious learning, there were special arrangements in prominent mosques. In the early years of Islam, the scholars from Arab countries used to come here frequently and some of them were entrusted with the charges of the Darses, higher learning centres, one such prominent institution was in Ponnani. -

The Cultural Shifts After Hadhrami Migration in Malabar

Imperial Journal of Interdisciplinary Research (IJIR) Vol-3, Issue-9, 2017 ISSN: 2454-1362, http://www.onlinejournal.in De-Persianaization of Islam: The Cultural Shifts after Hadhrami Migration in Malabar Anas Edoli Research Scholar, Department of History Sree Sankaracharya University of Sanskrit, Kalady. Abstract: Hadhrami migration to Malabar in the These reasons were enough to Hadhrami Sayyids to seventeenth century was a land mark issue in the oppose the Kondotty Thangals and their followers. history of Mappila Muslims and they influenced Hadhrami Sayyids started the campaign in early their socio-cultural life. They participated in the years of their migration against the views of religious affairs of Mappila Muslims as well as the Kondotty Thangal. Sheikh Jifri issued many anti colonial struggle against the British. It is Fatwas against them. In later years there emerged a worth mentioning that their role in De- constant dispute between Kondotty and Ponnani Persianaization of Islam in Malabar. In 17 the sect which was commonly known as Ponnani- century there was strong influence of the Kondotty Kondotty Kaitharam. Ponnani sect was of the Sunni Thangal in Malabar who propagated many Shia followers. Therefore Hadhrami Sayyids supported (Persian Islam) ideologies. Hadhrami Sayyids the Ponnani sect. fought against this ideology using their nail and teeth. Sheikh Jifri of Hadhramaut wrote a book 2. Influence of Persian Islam in Malabar against the Kondotty faction and Persian Islam lashing out at their rituals. This paper will analyze Muhammed Sha and his elder son and the activities of Hadhrami Sayyids towards the De- their followers started to propagate the Persian Persianaization of Islam in Malabar. -

The Islamic State in India's Kerala: a Primer

OCTOBER 2019 The Islamic State in India’s Kerala: A Primer KABIR TANEJA MOHAMMED SINAN SIYECH The Islamic State in India’s Kerala: A Primer KABIR TANEJA MOHAMMED SINAN SIYECH ABOUT THE AUTHORS Kabir Taneja is a Fellow with the Strategic Studies Programme of Observer Research Foundation. Mohammed Sinan Siyech is Research Analyst at the International Centre for Political Violence & Terrorism Research (ICPVTR) of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University (NTU) in Singapore. ISBN: 978-93-89094-97-8 © 2019 Observer Research Foundation. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from ORF. The Islamic State in India’s Kerala: A Primer ABSTRACT With a Muslim population of over 200 million, the third largest in the world next only to Indonesia and Pakistan, India was thought of by analysts to be fertile ground for the recruitment of foreign fighters for the Islamic State (IS). The country, however, has proven such analysts wrong by having only a handful of pro-IS cases so far. Of these cases, the majority have come from the southern state of Kerala. This paper offers an explanation for the growth of IS in Kerala. It examines the historical, social and political factors that have contributed to the resonance of IS ideology within specific regions of Kerala, and analyses the implications of these events to the overall challenge of countering violent extremism in India. (This paper is part of ORF's series, 'National Security'. Find other research in the series here: https://www.orfonline.org/series/national-security/) Attribution: Kabir Taneja and Mohammed Sinan Siyech, “The Islamic State in India’s Kerala: A Primer”, ORF Occasional Paper No. -

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for All People Groups & LR-Unreached People Groups = LR-Upgs

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & LR-Unreached People Groups = LR-UPGs - of INDIA Source: Joshua Project data, www.joshuaproject.net Western edition To order prayer resources or for inquiries, contact email: [email protected] I give credit & thanks to Create International for permission to use their PG photos. 2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & LR-UPGs = Least-Reached-Unreached People Groups of India INDIA SUMMARY: 2,717 total People Groups; 2,445 LR-UPG India has 1/3 of all UPGs in the world; the most of any country LR-UPG definition: 2% or less Evangelical & 5% or less Christian Frontier (FR) definition: 0% to 0.1% Christian Why pray--God loves lost: world UPGs = 7,407; Frontier = 5,042. Color code: green = begin new area; blue = begin new country Downloaded from www.joshuaproject.net in September 2020 * * * "Prayer is not the only thing we can can do, but it is the most important thing we can do!" * * * India ISO codes are used for some Indian states as follows: AN = Andeman & Nicobar. JH = Jharkhand OD = Odisha AP = Andhra Pradesh+Telangana JK = Jammu & Kashmir PB = Punjab AR = Arunachal Pradesh KA = Karnataka RJ = Rajasthan AS = Assam KL = Kerala SK = Sikkim BR = Bihar ML = Meghalaya TN = Tamil Nadu CT = Chhattisgarh MH = Maharashtra TR = Tripura DL = Delhi MN = Manipur UT = Uttarakhand GJ = Gujarat MP = Madhya Pradesh UP = Uttar Pradesh HP = Himachal Pradesh MZ = Mizoram WB = West Bengal HR = Haryana NL = Nagaland Why Should We Pray For Unreached People Groups? * Missions & salvation of all people is God's plan, God's will, God's heart, God's dream, Gen. -

Sociology Contributions to Indian

Contributions to Indian Sociology http://cis.sagepub.com Arabs, Moors and Muslims: Sri Lankan Muslim ethnicity in regional perspective Dennis B. McGilvray Contributions to Indian Sociology 1998; 32; 433 DOI: 10.1177/006996679803200213 The online version of this article can be found at: http://cis.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/32/2/433 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Contributions to Indian Sociology can be found at: Email Alerts: http://cis.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://cis.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations (this article cites 34 articles hosted on the SAGE Journals Online and HighWire Press platforms): http://cis.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/32/2/433 Downloaded from http://cis.sagepub.com at UNIV OF COLORADO LIBRARIES on August 31, 2008 © 1998 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution. Arabs, Moors and Muslims: Sri Lankan Muslim ethnicity in regional perspective Dennis B. McGilvray In the context of Sri Lanka’s inter-ethnic conflict between the Tamils and the Sinhalese, the Tamil- speaking Muslims or Moors occupy a unique position. Unlike the historically insurrectionist Māppilas of Kerala or the assimilationist Marakkāyars of coastal Tamilnadu, the Sri Lankan Muslim urban elite has fostered an Arab Islamic identity in the 20th century which has severed them from the Dravidian separatist campaign of the Hindu and Christian Tamils. This has placed the Muslim farmers in the Tamil-speaking north-eastern region in an awkward and dangeruus situation, because they would be geographically central to any future Tamil homeland.