Muslim Communities in Kerala to 1798

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Synonym to Conservation of Intangible Cultural Heritage: Folkland, International Centre for Folklore and Culture, Heading for Its 30Th Anniversary

A Synonym to Conservation of Intangible Cultural Heritage: Folkland, International Centre for Folklore and Culture, Heading for Its 30th Anniversary V. Jayarajan Folkland, International Centre for Folklore and Culture Folkland, International Centre for Folklore and Culture is an institution that was first registered on December 20, 1989 under the Societies Registration Act of 1860, vide No. 406/89. Over the last 16 years, it has passed through various stages of growth, especially in the fields of performance, production, documentation, and research, besides the preservation of folk art and culture. Since its inception in 1989, Folkland has passed through various phases of growth into a cultural organization with a global presence. As stated above, Folkland has delved deep into the fields of stage performance, production, documentation, and research, besides the preservation of folk art and culture. It has strived hard and treads the untrodden path with a clear motto of preservation and inculcation of old folk and cultural values in our society. Folkland has a veritable collection of folk songs, folk art forms, riddles, fables, myths, etc. that are on the verge of extinction. This collection has been recorded and archived well for scholastic endeavors and posterity. As such, Folkland defines itself as follows: 1. An international center for folklore and culture. 2. A cultural organization with clearly defined objectives and targets for research and the promotion of folk arts. Folkland has branched out and reached far and wide into almost every nook and corner of the world. The center has been credited with organizing many a festival on folk arts or workshop on folklore, culture, linguistics, etc. -

Authority, Knowledge and Practice in Unani Tibb in India, C. 1890

Authority, Knowledge and Practice in UnaniTibb in India, c. 1890 -1930 Guy Nicolas Anthony Attewell Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London ProQuest Number: 10673235 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673235 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This thesis breaks away from the prevailing notion of unanitibb as a ‘system’ of medicine by drawing attention to some key arenas in which unani practice was reinvented in the early twentieth century. Specialist and non-specialist media have projected unani tibb as a seamless continuation of Galenic and later West Asian ‘Islamic’ elaborations. In this thesis unani Jibb in early twentieth-century India is understood as a loosely conjoined set of healing practices which all drew, to various extents, on the understanding of the body as a site for the interplay of elemental forces, processes and fluids (humours). The thesis shows that in early twentieth-century unani ///)/; the boundaries between humoral, moral, religious and biomedical ideas were porous, fracturing the realities of unani practice beyond interpretations of suffering derived from a solely humoral perspective. -

Power Politics in Kolathunadu (1663-1697)

The Ali Rajas of Cannanore: status and identity at the interface of commercial and political expansion, 1663-1723 Mailaparambil, J.B. Citation Mailaparambil, J. B. (2007, December 12). The Ali Rajas of Cannanore: status and identity at the interface of commercial and political expansion, 1663-1723. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/12488 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/12488 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). CHAPTER SIX POWER POLITICS IN KOLATHUNADU (1663-1697) In the month of October 1690, three Dutch soldiers deserted from the Dutch fortress in Cannanore and were caught by the Nayars of the Kolathiri prince, Keppoe Unnithamburan, in Maday—a place some twenty kilometres to the north of Cannanore.1 Although they tried to hide their real identity by claiming first that they were English and later Portuguese, the Nayars who were sent by the Company to track them successfully exposed their pretensions. Realizing the graveness of the situation, the soldiers desperately pleaded with the Prince not to extradite them to the Company for fear of capital punishment. Moved by their pathetic imploring, the Prince took them under his protection and ordered the Company Nayars to turn back, stating that he would take them to Cannanore personally, which, in fact, did not happen. The Company servants complained about this incident to the Ali Raja. The latter assured them he would settle the issue by promising to advise and caution the inexperienced young prince regarding this issue. -

Saudi Arabia Under King Faisal

SAUDI ARABIA UNDER KING FAISAL ABSTRACT || T^EsIs SubiviiTTEd FOR TIIE DEqREE of ' * ISLAMIC STUDIES ' ^ O^ilal Ahmad OZuttp UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF DR. ABDUL ALI READER DEPARTMENT OF ISLAMIC STUDIES ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1997 /•, •^iX ,:Q. ABSTRACT It is a well-known fact of history that ever since the assassination of capital Uthman in 656 A.D. the Political importance of Central Arabia, the cradle of Islam , including its two holiest cities Mecca and Medina, paled into in insignificance. The fourth Rashidi Calif 'Ali bin Abi Talib had already left Medina and made Kufa in Iraq his new capital not only because it was the main base of his power, but also because the weight of the far-flung expanding Islamic Empire had shifted its centre of gravity to the north. From that time onwards even Mecca and Medina came into the news only once annually on the occasion of the Haj. It was for similar reasons that the 'Umayyads 661-750 A.D. ruled form Damascus in Syria, while the Abbasids (750- 1258 A.D ) made Baghdad in Iraq their capital. However , after a long gap of inertia, Central Arabia again came into the limelight of the Muslim world with the rise of the Wahhabi movement launched jointly by the religious reformer Muhammad ibn Abd al Wahhab and his ally Muhammad bin saud, a chieftain of the town of Dar'iyah situated between *Uyayana and Riyadh in the fertile Wadi Hanifa. There can be no denying the fact that the early rulers of the Saudi family succeeded in bringing about political stability in strife-torn Central Arabia by fusing together the numerous war-like Bedouin tribes and the settled communities into a political entity under the banner of standard, Unitarian Islam as revived and preached by Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab. -

PONNANI PEPPER PROJECT History Ponnani Is Popularly Known As “The Mecca of Kerala”

PONNANI PEPPER PROJECT HISTORY Ponnani is popularly known as “the Mecca of Kerala”. As an ancient harbour city, it was a major trading hub in the Malabar region, the northernmost end of the state. There are many tales that try to explain how the place got its name. According to one, the prominent Brahmin family of Azhvancherry Thambrakkal once held sway over the land. During their heydays, they offered ponnu aana [elephants made of gold] to the temples, and this gave the land the name “Ponnani”. According to another, due to trade, ponnu [gold] from the Arab lands reached India for the first time at this place, and thus caused it to be named “Ponnani”. It is believed that a place that is referred to as “Tyndis” in the Greek book titled Periplus of the Erythraean Sea is Ponnani. However historians have not been able to establish the exact location of Tyndis beyond doubt. Nor has any archaeological evidence been recovered to confirm this belief. Politically too, Ponnani had great importance in the past. The Zamorins (rulers of Calicut) considered Ponnani as their second headquarters. When Tipu Sultan invaded Kerala in 1766, Ponnani was annexed to the Mysore kingdom. Later when the British colonized the land, Ponnani came under the Bombay Province for a brief interval of time. Still later, it was annexed Malabar and was considered part of the Madras Province for one-and-a-half centuries. Until 1861, Ponnani was the headquarters of Koottanad taluk, and with the formation of the state of Kerala in 1956, it became a taluk in Palakkad district. -

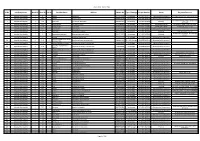

Sl No Localbody Name Ward No Door No Sub No Resident Name Address Mobile No Type of Damage Unique Number Status Rejection Remarks

Flood 2019 - Vythiri Taluk Sl No Localbody Name Ward No Door No Sub No Resident Name Address Mobile No Type of Damage Unique Number Status Rejection Remarks 1 Kalpetta Municipality 1 0 kamala neduelam 8157916492 No damage 31219021600235 Approved(Disbursement) RATION CARD DETAILS NOT AVAILABLE 2 Kalpetta Municipality 1 135 sabitha strange nivas 8086336019 No damage 31219021600240 Disbursed to Government 3 Kalpetta Municipality 1 138 manjusha sukrutham nedunilam 7902821756 No damage 31219021600076 Pending THE ADHAR CARD UPDATED ANOTHER ACCOUNT 4 Kalpetta Municipality 1 144 devi krishnan kottachira colony 9526684873 No damage 31219021600129 Verified(LRC Office) NO BRANCH NAME AND IFSC CODE 5 Kalpetta Municipality 1 149 janakiyamma kozhatatta 9495478641 >75% Damage 31219021600080 Verified(LRC Office) PASSBOOK IS NO CLEAR 6 Kalpetta Municipality 1 151 anandavalli kozhathatta 9656336368 No damage 31219021600061 Disbursed to Government 7 Kalpetta Municipality 1 16 chandran nedunilam st colony 9747347814 No damage 31219021600190 Withheld PASSBOOK NOT CLEAR 8 Kalpetta Municipality 1 16 3 sangeetha pradeepan rajasree gives nedunelam 9656256950 No damage 31219021600090 Withheld No damage type details and damage photos 9 Kalpetta Municipality 1 161 shylaja sasneham nedunilam 9349625411 No damage 31219021600074 Disbursed to Government Manjusha padikkandi house 10 Kalpetta Municipality 1 172 3 maniyancode padikkandi house maniyancode 9656467963 16 - 29% Damage 31219021600072 Disbursed to Government 11 Kalpetta Municipality 1 175 vinod madakkunnu colony -

Panchadik2010

Konkani Association of California panchadik 2010 (September – November) Copyright © 2010 Konkani Association of California (KAOCA) All rights reserved. Table of Contents 1. President’s Corner.……………………………………………………. 3 2. Kidz Korner.………………………………………………………………. 6 3. Konkani – origin and history…..….……………………………. 16 4. Hoon Khabbar……………………………………………………………. 20 5. Do you know our Amchis?...…………………………………….. 23 6. Konkani Bytes……………………………………………………………. 27 Copyright © 2010 Konkani Association of California (KAOCA) 2 All rights reserved. 1. President's Corner Namaskaru, It gives us immense pleasure to inform that our final event - “Diwali” in 2010 was a grand success. We had over 350 people attend this event in San Jose. The entire KAOCA committee thanks the patrons who helped make this event a huge success. The event started at 4 pm with snacks, which included Masala Puri and Shira. The Entertainment program started at 5 pm and had a variety of programs including a couple of skits. The dinner followed at 8:15 pm and the menu included Valval, Ambe Upkari, Veg Kurma and Chicken Curry. The evening ended on a high note after the DJ music. It is time now for us – the 2010 KAOCA committee to move on and reflect back on the nostalgic journey which started late in 2009. On a personal note, when Sulatha and I were approached to head the committee for 2010, I was not very sure. However, my wife the charmer she is, talked me into it. “Yes we can” was her slogan and that triggered enough adrenaline rush in me to stand up and take the mantle. That is one side of the story. The other is the fabulous committee that made all of this happen. -

Website Complete List of Ra

University Grants Commission Bahadurshah Zafar Marg New Delhi- 110002 Ph.No: 011-23234840(O) Email.: [email protected] SPEED POST No.F.30-1/2012(SA-II) September , 2013 To ______________ Sub.: Interface meeting of Research Award-(12-14) Sir/Madam, This is with reference to your online application for Research Award for the year 2012-14. After screening of applications, the Commission has now constituted a Selection Committee for identifying the suitable candidate under the scheme. An interface meeting with the expert(s) will be held on __________ at 10.30 a.m. in the office of University Grants Commission, Bahadurshah Zafar Marg, ITO, New Delhi- 110002 in --------------- subject. You are requested to attend and present your proposal. Please bring a set of your project proposal/application and other necessary documents. No TA/DA will be paid by the Commission for attending this meeting. Yours faithfully, -Sd- (Ms. Sudha Rani) Under Secretary PS: This is computer generated letter. Signature is not necessary. NB: Schedule of Interface meeting is available on UGC Website: www.ugc.ac.in If your name is available in the schedule this letter may be treated as final copy 1 List of Shortlisted Candidates Under Research Award 2012-14 Venue:-UGC, Bahadurshah Zafar Marg, (ITO) New Delhi-110002 Sr. Candidate ID Name Address Subject Date of University Name No. Meeting 1 RA-2012-14- NIKHIL MOORCHUNG ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR, DEPT Biology 07.10.2013 ARMED FORCES GE-MAH-754 OF PATHOLOGY ARMED MEDICAL COLLEGE, FORCES MEDICAL COLLEGE, SHOLAPUR ROAD, 2 RA-2012-14- KAVINDRA KUMAR KavindraSHOLAPUR Kumar ROAD Kesari C/O Prof. -

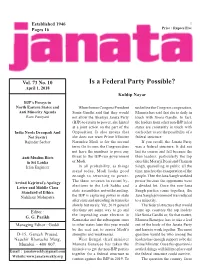

Is a Federal Party Possible?

Established 1946 1 Pages 16 Price : Rupees Five Vol. 73 No. 10 Is a Federal Party Possible? April 1, 2018 Kuldip Nayar BJP’s Forays in North Eastern States and When former Congress President underline the Congress cooperation, Anti Minority Agenda Sonia Gandhi said that they would Mamata has said that she is daily in Ram Puniyani not allow the Bhartiya Janata Party touch with Sonia Gandhi. In fact, (BJP) to return to power, she hinted the leaders from other non-BJP ruled at a joint action on the part of the states are constantly in touch with India Needs Draupadi And Opposition. It also means that each other to see the possibility of a Not Savitri she does not want Prime Minister federal structure. Rajindar Sachar Narendra Modi to for the second If you recall, the Janata Party term. On its own, the Congress does was a federal structure. It did not not have the numbers to pose any last its course and fell because the Anti-Muslim Riots threat to the BJP-run government then leaders, particularly the top in Sri Lanka or Modi. ones like Morarji Desai and Chanran Irfan Engineer In all probability, as things Singh, quarrelling in public all the stand today, Modi looks good time, much to the exasperation of the enough to returning to power. people. Then the Jana Sangh wielded The three reverses in recent by- power because the opponents were Arvind Kejriwal’s Apology elections to the Lok Sabha and a divided lot. Once the non-Jana Letter and Middle Class Standard of Ethics state assemblies notwithstanding, Sangh parties came together, the Nishikant Mohapatra the BJP is capturing power in state Jana Sangh government was reduced after state and spreading its tentacles to a minority. -

Digital Religion

DIGITAL RELIGION DIGITAL RELIGION Based on papers read at the conference arranged by the Donner Institute for Research in Religious and Cultural History, Åbo Akademi University, Åbo/Turku, Finland, on 13–15 June 2012 Edited by Tore Ahlbäck Editorial Assistant Björn Dahla Published by the Donner Institute for Research in Religious and Cultural History Åbo/Turku, Finland Distributed by BTJ Finland Editorial secretary Maria Vasenkari Linguistic editing Sarah Bannock ISSN 0582-3226 ISBN 978-952-12-2897-1 Printed in Finland by Vammalan kirjapaino Sastamala 2013 Editorial note he theme for our symposium 2012 was ‘Digital religion’ and in our call Tfor papers we described it in the following way: ‘ “Digital Religion’ aims to explore the complex relationship between religion and digital technologies of communication. Digital religion encompasses a myriad of connections and the goal of the conference is to approach the subject from multiple perspec- tives.’ As can be seen from the conference proceedings, we did not achieve what we aimed for. The theme was too vast. We knew as much; a new field is always difficult to handle. Despite this, we still hope that the participants got some- thing out of the conference, and we also hope that the readers of the proceed- ings will benefit from them. I wish to finish this editorial note by acknowledging my colleague Björn Dahla. For many years we organised the Donner symposia and edited the conference proceedings together. I owe him my sincere gratitude. I also want to warmly thank Maria Vasenkari who, for many years, did the necessary, extensive technical work in order to follow the conference pro- ceedings through into print. -

MALAPPURAM DISTRICT College of Engg. Trivandrum Mohammed

MALAPPURAM DISTRICT College of engg. Trivandrum Mohammed Shajahan P COCHIN COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY ABDUL AZEEZ C Government Engineering College Thrissur ABDUL AZEEZ KT Federal Institute of Science and Technology Abdul Basith Government Engineering College, Wayanad Abdul Basith K GEC palakkad Abdul Mahroof N MEA Engineering college perinthalmanna ABDUL MAJID K T Gov. Engineering college kozhikode Abdul Muhsin v Mes college of engineering Abdul Rishad Mes college of engineering Abdul Rishad Malabar Polytechnic college, Kottakkal Abdul Vahid B. S MES COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING,KUTTIPPURAM ABDUL VARIS N FISAT Abhay Krishna SD Tkm college of engineering Abhijit k Nehru college of engineering and reasearch centre Abhijith uk MES CET, KUNNUKARA Abhimanyu ks TKM College Of Engineering, Kollam ABHIRAJ.P COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING KOTTARAKKARA ABHIRAM P COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING TRIVANDATUM ABHIRAM P jawaharlal college of engineering and technology Abhishek A S Sreepathy institute of Management and technology Abijith g GEC PALAKKAD ADARSH DAS N Lal Bahadur Shastri College of Engineering, ADARSH DAS.P Eranad Knowledge City Technical Campus Adhil Fuad M.E.S College Of Engineering Adhin Gopuj.A COCHIN COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY ADHINI ULLAS AK COCHIN COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY ADHINI ULLAS AK COCHIN COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY VALANCHERI ADHINI ULLAS AK GOVERNMENT ENGINEERING COLLEGE THRISSUR ADITHYA KUMAR M S Al ameen engineering college Adnan mohamed ali College of Engineering Trivandrum Afnan Mohammed A Government engineering college idukki Aghil.P MESCE AHAMED SHAMZAD MK MEA Engineering College Perinthalmanna Ahammed Jouhar E T Mes engineering college kuttipuram Ahammed rasheek Government Engineering College Thrissur AHNAS P P Ncerc Ajay Anand C Govt. -

EDUCATIONAL DISTRICT - MALAPPURAM Sl

LIST OF HIGH SCHOOLS IN MALAPPURAM DISTRICT EDUCATIONAL DISTRICT - MALAPPURAM Sl. Std. Std. HS/HSS/VHSS Boys/G Name of Name of School Address with Pincode Block Taluk No. (Fro (To) /HSS & irls/ Panchayat/Muncip m) VHSS/TTI Mixed ality/Corporation GOVERNMENT SCHOOLS 1 Arimbra GVHSS Arimbra - 673638 VIII XII HSS & VHSS Mixed Morayur Malappuram Eranad 2 Edavanna GVHSS Edavanna - 676541 V XII HSS & VHSS Mixed Edavanna Wandoor Nilambur 3 Irumbuzhi GHSS Irumbuzhi - 676513 VIII XII HSS Mixed Anakkayam Malappuram Eranad 4 Kadungapuram GHSS Kadungapuram - 679321 I XII HSS Mixed Puzhakkattiri Mankada Perinthalmanna 5 Karakunnu GHSS Karakunnu - 676123 VIII XII HSS Mixed Thrikkalangode Wandoor Eranad 6 Kondotty GVHSS Melangadi, Kondotty - 676 338. V XII HSS & VHSS Mixed Kondotty Kondotty Eranad 7 Kottakkal GRHSS Kottakkal - 676503 V XII HSS Mixed Kottakkal Malappuram Tirur 8 Kottappuram GHSS Andiyoorkunnu - 673637 V XII HSS Mixed Pulikkal Kondotty Eranad 9 Kuzhimanna GHSS Kuzhimanna - 673641 V XII HSS Mixed Kuzhimanna Areacode Eranad 10 Makkarapparamba GVHSS Makkaraparamba - 676507 VIII XII HSS & VHSS Mixed Makkaraparamba Mankada Perinthalmanna 11 Malappuram GBHSS Down Hill - 676519 V XII HSS Boys Malappuram ( M ) Malappuram Eranad 12 Malappuram GGHSS Down Hill - 676519 V XII HSS Girls Malappuram ( M ) Malappuram Eranad 13 Manjeri GBHSS Manjeri - 676121 V XII HSS Mixed Manjeri ( M ) Areacode Eranad 14 Manjeri GGHSS Manjeri - 676121 V XII HSS Girls Manjeri ( M ) Areacode Eranad 15 Mankada GVHSS Mankada - 679324 V XII HSS & VHSS Mixed Mankada Mankada