Power Politics in Kolathunadu (1663-1697)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Particulars of Some Temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of Some

Particulars of some temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of some temples of Kerala .............................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 9 Temples of Kerala ................................................................................. 10 Temples of Kerala- an over view .................................................... 16 1. Achan Koil Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 23 2. Alathiyur Perumthiri(Hanuman) koil ................................. 24 3. Randu Moorthi temple of Alathur......................................... 27 4. Ambalappuzha Krishnan temple ........................................... 28 5. Amedha Saptha Mathruka Temple ....................................... 31 6. Ananteswar temple of Manjeswar ........................................ 35 7. Anchumana temple , Padivattam, Edapalli....................... 36 8. Aranmula Parthasarathy Temple ......................................... 38 9. Arathil Bhagawathi temple ..................................................... 41 10. Arpuda Narayana temple, Thirukodithaanam ................. 45 11. Aryankavu Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 47 12. Athingal Bhairavi temple ......................................................... 48 13. Attukkal BHagawathy Kshethram, Trivandrum ............. 50 14. Ayilur Akhileswaran (Shiva) and Sri Krishna temples ........................................................................................................... -

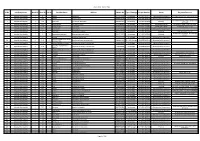

Sl No Localbody Name Ward No Door No Sub No Resident Name Address Mobile No Type of Damage Unique Number Status Rejection Remarks

Flood 2019 - Vythiri Taluk Sl No Localbody Name Ward No Door No Sub No Resident Name Address Mobile No Type of Damage Unique Number Status Rejection Remarks 1 Kalpetta Municipality 1 0 kamala neduelam 8157916492 No damage 31219021600235 Approved(Disbursement) RATION CARD DETAILS NOT AVAILABLE 2 Kalpetta Municipality 1 135 sabitha strange nivas 8086336019 No damage 31219021600240 Disbursed to Government 3 Kalpetta Municipality 1 138 manjusha sukrutham nedunilam 7902821756 No damage 31219021600076 Pending THE ADHAR CARD UPDATED ANOTHER ACCOUNT 4 Kalpetta Municipality 1 144 devi krishnan kottachira colony 9526684873 No damage 31219021600129 Verified(LRC Office) NO BRANCH NAME AND IFSC CODE 5 Kalpetta Municipality 1 149 janakiyamma kozhatatta 9495478641 >75% Damage 31219021600080 Verified(LRC Office) PASSBOOK IS NO CLEAR 6 Kalpetta Municipality 1 151 anandavalli kozhathatta 9656336368 No damage 31219021600061 Disbursed to Government 7 Kalpetta Municipality 1 16 chandran nedunilam st colony 9747347814 No damage 31219021600190 Withheld PASSBOOK NOT CLEAR 8 Kalpetta Municipality 1 16 3 sangeetha pradeepan rajasree gives nedunelam 9656256950 No damage 31219021600090 Withheld No damage type details and damage photos 9 Kalpetta Municipality 1 161 shylaja sasneham nedunilam 9349625411 No damage 31219021600074 Disbursed to Government Manjusha padikkandi house 10 Kalpetta Municipality 1 172 3 maniyancode padikkandi house maniyancode 9656467963 16 - 29% Damage 31219021600072 Disbursed to Government 11 Kalpetta Municipality 1 175 vinod madakkunnu colony -

Mehendale Book-10418

Tipu as He Really Was Gajanan Bhaskar Mehendale Tipu as He Really Was Copyright © Gajanan Bhaskar Mehendale First Edition : April, 2018 Type Setting and Layout : Mrs. Rohini R. Ambudkar III Preface Tipu is an object of reverence in Pakistan; naturally so, as he lived and died for Islam. A Street in Islamabad (Rawalpindi) is named after him. A missile developed by Pakistan bears his name. Even in India there is no lack of his admirers. Recently the Government of Karnataka decided to celebrate his birth anniversary, a decision which generated considerable opposition. While the official line was that Tipu was a freedom fighter, a liberal, tolerant and enlightened ruler, its opponents accused that he was a bigot, a mass murderer, a rapist. This book is written to show him as he really was. To state it briefly: If Tipu would have been allowed to have his way, most probably, there would have been, besides an East and a West Pakistan, a South Pakistan as well. At the least there would have been a refractory state like the Nizam's. His suppression in 1792, and ultimate destruction in 1799, had therefore a profound impact on the history of India. There is a class of historians who, for a long time, are portraying Tipu as a benevolent ruler. To counter them I can do no better than to follow Dr. R. C. Majumdar: “This … tendency”, he writes, “to make history the vehicle of certain definite political, social and economic ideas, which reign supreme in each country for the time being, is like a cloud, at present no bigger than a man's hand, but which may soon grow in volume, and overcast the sky, covering the light of the world by an impenetrable gloom. -

The Chirakkal Dynasty: Readings Through History

THE CHIRAKKAL DYNASTY: READINGS THROUGH HISTORY Kolathunadu is regarded as one of the old political dynasties in India and was ruled by the Kolathiris. The Mushaka vamsam and the kings were regarded as the ancestors of the Kolathiris. It was mentioned in the Mooshika Vamsa (1980) that the boundary of Mooshaka kingdom was from the North of Mangalapuram – Puthupattanam to the Southern boundary of Korappuzha in Kerala. In the long Sanskrit historical poem Mooshaka Vamsam, the dynastic name of the chieftains of north Malabar (Puzhinad) used is Mooshaka (Aiyappan, 1982). In the beginning of the fifth Century A.D., the kingdom of Ezhimala had risen to political prominence in north Kerala under Nannan… With the death of Nannan ended the most glorious period in the history of the Ezhimala Kingdom… a separate line of rulers known as the Mooshaka kings held sway over this area 36 (Kolathunad) with their capital near Mount Eli. It is not clear whether this line of rulers who are celebrated in the Mooshaka vamsa were subordinate to the Chera rulers of Mahodayapuram or whether they ruled as an independent line of kings on their own right (in Menon, 1972). The narration of the Mooshaka Kingdom up to the 12th Century A.D. is mentioned in the Mooshaka vamsa. This is a kavya (poem) composed by Atula, who was the court poet of the King Srikantha of Mooshaka vamsa. By the 14th Century the old Mooshaka kingdom had come to be known as Kolathunad and a new line of rulers known as the Kolathiris (the ‘Colastri’ of European writers) had come into prominence in north Kerala. -

Admission Closing Officials List 2018.Xlsx

Name and Sl. Designation of Sl. No. Details of Institute to be closed ITI Code District No. Admission Clossing Official 1 Vice Principal, Government Industrial Training Institute, Attingal, Govt. ITI Chackai. 1 Attingal.P.O GR32000246 Thiruvananthapuram Government Industrial Training Institute (SCDD) 2 Singarathoppu, Manacaud. GU32000377 Thiruvananthapuram 3 M P Private Industrial Training Institute, Attakulangara. PR32000226 Thiruvananthapuram Polio Home Computer Training Centre Private Industrial 4 Training Institute, LMS Compound, Palayam. PR32000400 Thiruvananthapuram All Saint's Computer Centre Private Industrial Training, 5 Beach.P.O PR32000417 Thiruvananthapuram 6 Jayamatha Private Industrial Training Institute, Nalanchira. PU32000288 Thiruvananthapuram Vice Principal, 2 Govt. ITI Government Industrial Training Institute for Women Dhanuvachapuram 1 Parassala GR32000639 Thiruvananthapuram Government Industrial Training Institute (SCDD) 2 Kanjiramkulam, Pulluvila.P.O. PR32000176 Thiruvananthapuram C.S.I Private Industrial Training Institute, 3 Kodiyannoorkonam, Thannimoodu.P.O PR32000123 Thiruvananthapuram Viswabharathy Private Industrial Training Institute, 4 Viswabharathy Road, Neyyattinkara. PR32000187 Thiruvananthapuram Bharat Social Service Centre Private Industrial Training 5 Institute, Paraniyam, Poovar. PR32000194 Thiruvananthapuram Institute of Engineering Technology Private Industrial 6 Training Institute, Kanjiramkulam, Nellikkakuzhi PR32000314 Thiruvananthapuram Computer Park Private Industrial Training Institute, 7 Neyyattinkara.P.O. -

15 -ാം േകരള നിയമസഭ 1 -ാം സേ ളനം ന ചി ം ഇ ാ േചാദ ം നം . 138 07-06

15 -ാം േകരള നിയമസഭ 1 -ാം സേളനം ന ചിം ഇാ േചാദം നം. 138 07-06-2021 - ൽ മപടി് ളയിൽ തകർ േറാകൾ േചാദം ഉരം Shri M. V. Govindan Master ീ . സി േജാസഫ് (തേശസയംഭരണം ാമവികസനം എൈം വ് മി) (എ) (എ) 2018, 2019 വർഷിൽ ഉായ ളയിൽ 2018, 2019 വർഷളിൽ ഉായ ളയിൽ തകർ കർ ജിയിെല േറാകെട എം തകർ ാമീണ േറാകൾ എ; അവ 877 ആണ്. േറാകൾ് 109.236 േകാടി ഏെതാെ; എ േകാടിെട നാശനളാണ് പെട നാശനളാണ് ഉായിത്. േറാകൾ് ഉായിത്; ത ത േറാകൾക് 76.289181 േകാടി പ േറാകൾ് ഫ് അവദിിോ; ഉെിൽ അവദിി്. ത േറാകെടം എ ക ഏെതാം േറാകൾെ് അവദി കെടം വിശദാംശൾ യഥാമം വിശദമാേമാ; അബം I, II എിവയിൽ കാണാതാണ് . (ബി) ളയിൽ തകർ പല ാമീണ േറാകം (ബി) നവീകരിതിന് ഫ് അവദിാത് ളയിൽ തകർ ാമീണ േറാകൾ യിൽെിോ: ആയ നവീകരിതിനാവശമായ നടപടികൾ സീകരി നവീകരിതിനാവശമായ നടപടി വരികയാണ്. സീകരിേമാ? െസൻ ഓഫീസർ 1 of 1 LSGD DIVISION, KANNUR LSGD SUB DIVISION, TALIPARAMBA BLOCK PANCHAYATH LIST OF ROADS, CULVERTS & BRIDGES DAMAGED DURING FLOOD 2018 Name of Width of Road Name of Block Length of Road Width of Carriage way Sl No Name of Constituency Panchayath/Muncipality/C Name of Road, Bridge, Culvert, Building (in m) Amount Remarks Panchayath (in km) (in m) orporation RoW=Right of Way 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 ₹8 12 300 m concrere drain is proposed since there is no RoW greater than 3.0m & 1 Irikkoor Thaliparamba Udayagiri GP Anakkuzhi-Kappimala 0.3 3.00m ₹10,00,000 outlet available retarring less than 5.5m works are also to be arranged One culvert is to be constructed in the given RoW greater than 3.0m & chainage and road work for 2 Irikkoor Thaliparamba Udayagiri GP Mampoyil - Kanayankalpadi 1 3.00m ₹11,46,810 less than 5.5m the completely destroyed portions were arranged by GP Densily populated region RoW greater than 3.0m & majority of the dwellers 3 Irikkoor Thaliparamba Udayagiri GP Munderithatt - Thalathanni Road 1 3.00m ₹10,00,000 less than 5.5m belongs to Backward Community Concrete Drains,side RoW greater than 3.0m & protections works and pipe 4 Irikkoor Thaliparamba Udayagiri GP Kattappalli-Sreegiri-Mukkuzhi road 1.3 3.00m ₹5,00,000 less than 5.5m culverts are to be constructed. -

Kannur International Airport, Kerala, India EPC I

GOVERNMENT OF KERALA KANNUR INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT LIMITED REQUEST FOR QUALIFICATION (RFQ) Kannur International Airport, Kerala, India EPC I Detailed Designing, Engineering, Procurement and Construction of Earth Work and Pavements for Runway, Basic Strips, Turning Pads, Taxiways, Apron, Access Roads, Drainage System, Related Retaining Structures, Formation Platforms for Landside Facilities and Design, Supply, Installation, Testing and Commissioning of Airfield Ground Lighting System, Visual Aids for Navigation and Bird Hazard Reduction System.(herein after referred to as Project) 'Parvathy',T.C 36/1, Chackai, N.H Bypass, Thiruvananthapuram 695 024, Kerala, INDIA Ph: +91 471 2508668, 2508670, Fax: +91 471 2508669 E-mail: [email protected] January 2013 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS SI. No. Contents Page No. Disclaimer 4 1 Introduction 6 1.1 Background 6 1.2 Scope of Work and eligibility of Applicant 12 1.3 Brief description of Bidding Process 15 1.4 Schedule of Bidding Process 16 2 Instructions to Applicants 17 2A General 17 2.1 Scope of Application 17 2.2 Pre- Qualifying Criteria (PQ) for Works contracts 17 2.3 Change in composition of the Joint Venture / Consortium 21 2.4 Number of Applications and costs thereof 22 2.5 Site visit and verification of information 22 2.6 Acknowledgement by Applicant 22 2.7 Right to accept or reject any or all Applications/ Bids 23 2B Documents 24 2.8 Contents of the RFQ 24 2.9 Clarifications 24 2.10 Amendment of RFQ 25 2C Preparation and Submission of Application 25 2.11 Language 25 2.12 Format and -

Tbe Origin of Tbe Nair Rebellion of 1766

APPENDIX I TBE ORIGIN OF TBE NAIR REBELLION OF 1766 Some interesting conclusions can be drawn from the Dutch letters with respect to Haidar's movements following his conquest of Calicut and to the origin of the Nair rebellion, conclusions which as will be seen do not correspond with the genera11y accepted view of these events. Beginning with the latter, Hayavadana Rao, when describing them, refers to Wilks, Kirmani, the Haidar-Namah, Robson, but mainly to de la Tour. Rao then writes: "All this took nearly a montb from the day Mana-Vikrama put hirnself to death in such an extraordinary fashion. Haidar then moved further south-west, with the view of reducing the country as far as Travancore, thus completing his designs of the conquest of the whole of the Western Coast from Goa onwards. He had the more reason to do this now, as he suspected that the sons of the N air chiefs of Malabar - including those belonging to the Kolattiri and Zamorin families - had taken counsel with the kings of Travancore and Cochin, and had collected a large army at Ponnani, about 36 miles to the south of Calicut. Their forces assembled on the banks of the river of the same name, and were assisted by a few European gunners and Portuguese artisans. These, however, precipitately withdrew, immediately Haidar made his appearance. He pursued them as far as Cochin, some fifty miles further to tbe southward where, by the mediation of the Dutch, the king of Cochin made peace with hirn by agreeing to pay tribute to M ysore. -

World History Bulletin Fall 2016 Vol XXXII No

World History Bulletin Fall 2016 Vol XXXII No. 2 World History Association Denis Gainty Editor [email protected] Editor’s Note From the Executive Director 1 Letter from the President 2 Special Section: The World and The Sea Introduction: The Sea in World History 4 Michael Laver (Rochester Institute of Technology) From World War to World Law: Elisabeth Mann Borgese and the Law of the Sea 5 Richard Samuel Deese (Boston University) The Spanish Empire and the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans: Imperial Highways in a Polycentric Monarchy 9 Eva Maria Mehl (University of North Carolina Wilmington) Restoring Seas 14 Malcolm Campbell (University of Auckland) Ship Symbolism in the ‘Arabic Cosmopolis’: Reading Kunjayin Musliyar’s “Kappapattu” in 18th Century Malabar 17 Shaheen Kelachan Thodika (Jawaharlal Nehru University) The Panopticon Comes Full Circle? 25 Sarah Schneewind (University of California San Diego) Book Review 29 Abeer Saha (University of Virginia) practical ideas for the classroom; she intro- duces her course on French colonialism in Domesticating the “Queen of Haiti, Algeria, and Vietnam, and explains how Beans”: How Old Regime France aseemingly esoteric topic like the French empirecan appear profoundly relevant to stu- Learned to Love Coffee* dents in Southern California. Michael G. Vann’sessay turns our attention to the twenti- Julia Landweber eth century and to Indochina. He argues that Montclair State University both French historians and world historians would benefit from agreater attention to Many goods which students today think of Vietnamese history,and that this history is an as quintessentially European or “Western” ideal means for teaching students about cru- began commercial life in Africa and Asia. -

Handbooks Kerala

district handbooks of kerala CANNANORE DIREtTORATE OF , roBLICRElATIONS DISTRICT HANDBOOKS OF KERALA CANNANORE DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC RELATIONS Sli). NaticBttl Systems VuiU Naiiori-I Institute of Educational Planning and A ministration 1 7 -B.StiAV V 'ndo CONTENTS Page 1. Short history of Cannanore 1 2. Topography and Climate 2 3. Religions 3 4 . Customs and Manners 6 5. Kalari 7 6. Industries 8 7. Animal Husbandry 9 8. Special Agricultural Development Unit 9 9. Fisheries 10 10. Communication and Transport 11 11. Education 11 12. Medical Facilities 11 13. Forests 12 14 , Professional and Technical Institutions 13 15. Religious Institutions 14 16 . Places of Interest 16 17 . District at a glance 21 18 . Blocks and Panchayats 22 PART I Cannanore is the anglicised form oF the Malayalam word “ Karinur” . According to one view “ Kannur” is the variation of Kanathur, an ancient village, the name of which survive even today in ont! of the wards of Canna nore MunicipaUty. Perhaps, like several other ancient towns of Kerala, Cannanore also is named after one of the deities of the Hindu Pantheon. Thus “ Kannur” is the compound of the two words ‘Kannan’ meaning Lord Kris;hna, and TJr’ meaning place, the place of Lord Krishna, Short history of Cannanore Cannanore, the northernmost district of Kerala State, is constituted of territories which formed part of the erst while district ol' Malabar and South Ganara, prior to the rc-organisation of the States in 1956. Cannanore district was formed on January 1, 1957 by trifurcating the erstwhile Malabar district of the former Madras State. The district has a distinct history of its own which is in many rcspects independent of the history of other regions oi the State. -

Ahtl-European STRUGGLE by the MAPPILAS of MALABAR 1498-1921 AD

AHTl-EUROPEAn STRUGGLE BY THE MAPPILAS OF MALABAR 1498-1921 AD THESIS SUBMITTED FDR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE DF Sactnr of pitilnsopliQ IN HISTORY BY Supervisor Co-supervisor PROF. TARIQ AHMAD DR. KUNHALI V. Centre of Advanced Study Professor Department of History Department of History Aligarh Muslim University University of Calicut Al.garh (INDIA) Kerala (INDIA) T6479 VEVICATEV TO MY FAMILY CONTENTS SUPERVISORS' CERTIFICATE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT LIST OF MAPS LIST OF APPENDICES ABBREVIATIONS Page No. INTRODUCTION 1-9 CHAPTER I ADVENT OF ISLAM IN KERALA 10-37 CHAPTER II ARAB TRADE BEFORE THE COMING OF THE PORTUGUESE 38-59 CHAPTER III ARRIVAL OF THE PORTUGUESE AND ITS IMPACT ON THE SOCIETY 60-103 CHAPTER IV THE STRUGGLE OF THE MAPPILAS AGAINST THE BRITISH RULE IN 19™ CENTURY 104-177 CHAPTER V THE KHILAFAT MOVEMENT 178-222 CONCLUSION 223-228 GLOSSARY 229-231 MAPS 232-238 BIBLIOGRAPHY 239-265 APPENDICES 266-304 CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH - 202 002, INDIA CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis "And - European Struggle by the Mappilas of Malabar 1498-1921 A.D." submitted for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Aligarh Muslim University, is a record of bonafide research carried out by Salahudheen O.P. under our supervision. No part of the thesis has been submitted for award of any degree before. Supervisor Co-Supervisor Prof. Tariq Ahmad Dr. Kunhali.V. Centre of Advanced Study Prof. Department of History Department of History University of Calicut A.M.U. Aligarh Kerala ACKNOWLEDGEMENT My earnest gratitude is due to many scholars teachers and friends for assisting me in this work. -

Ancestral Centers of Kerala Muslim Socio- Cultural and Educational Enlightenments Dr

© 2019 JETIR June 2019, Volume 6, Issue 6 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Ancestral Centers of Kerala Muslim Socio- Cultural and Educational Enlightenments Dr. A P Alavi Bin Mohamed Bin Ahamed Associate Professor of Islamic history Post Graduate and Research Department of Islamic History, Government College, Malappuram. Abstract: This piece of research paper attempts to show that the genesis and growth of Islam, a monotheistic religion in Kerala. Of the Indian states, Malabar was the most important state with which the Arabs engaged in trade from very ancient time. Advance of Islam in Kerala,it is even today a matter of controversy. Any way as per the established authentic historical records, we can definitely conclude that Islam reached Kerala coast through the peaceful propagation of Arab-Muslim traders during the life time of prophet Muhammad. Muslims had been the torch bearers of knowledge and learning during the middle ages. Traditional education centres, i.e Maqthabs, Othupallis, Madrasas and Darses were the ancestral centres of socio-cultural and educational enlightenments, where a new language, Arabic-Malayalam took its birth. It was widely used to impart educational process and to exhort anti-colonial feelings and religious preaching in Medieval Kerala. Keywords: Darses, Arabi-Malayalam, Othupalli, Madrasa. Introduction: Movements of revitalization, renewal and reform are periodically found in the glorious history of Islam since its very beginning. For higher religious learning, there were special arrangements in prominent mosques. In the early years of Islam, the scholars from Arab countries used to come here frequently and some of them were entrusted with the charges of the Darses, higher learning centres, one such prominent institution was in Ponnani.